Two Americas

Why is American political discourse so radically different than the daily life of Americans?

Like much of humanity outside the United States — I’m Canadian — I’ve been spending far too much time following the American election campaign. Unlike most outsiders, however, I’ve also been travelling widely in the US, speaking with an array of audiences, and having conversations along the way.

The combination of these two experiences has inflicted massive cognitive dissonance on my poor brain.

As a foreigner following American news and social media, the United States I see is — no surprise to anyone paying attention — profoundly fractured. Americans are divided into camps that spend their days alternately shouting at each other and expressing bewilderment that the other side could possibly support such obvious madness.

They are stupid. They are ignorant. They are deluded. They mindlessly regurgitate the propaganda they are fed by their cynical mind-manipulating media and leaders.

And they are dangerous. If they win, they will destroy democracy.

We must fight.

This America feels like end-stage Yugoslavia.

But as a foreigner travelling the United States, the America I see is … pretty much the United States I’ve known and liked my whole life. As always, Americans are ridiculously friendly and will happily talk a stranger’s ear off about sports or the weather or any old thing. They work hard and put in long hours. They’ve got plans and ambitions. There’s a reason why the American economy remains the world’s largest and most dynamic, as it has been since the late 19th century.

What I don’t see while travelling the United States is much evidence of the closest, most fraught presidential election in modern history.

I have stood for God-only-knows how many hours in airport security lineups without seeing even one “Make America Great” ballcap or “Harris/Walz 2024” t-shirt. Not a single campaign button. Even lawn signs are so scarce they’re badly outnumbered by “now hiring” signs on businesses.

And for all the talking those friendly Americans do, I overheard precisely no one discussing politics. The only time the subject ever came up was when a nosy Canadian writer asked about it.

In all my conversations, I knew I must be talking to some mix of Republicans and Democrats but if I were to set aside geography and statistical base rates, there was never a moment, not one, when I could have guessed if I were speaking to an R or a D. They all just sounded like Americans to me.

This America? This America is doing just fine, thanks.

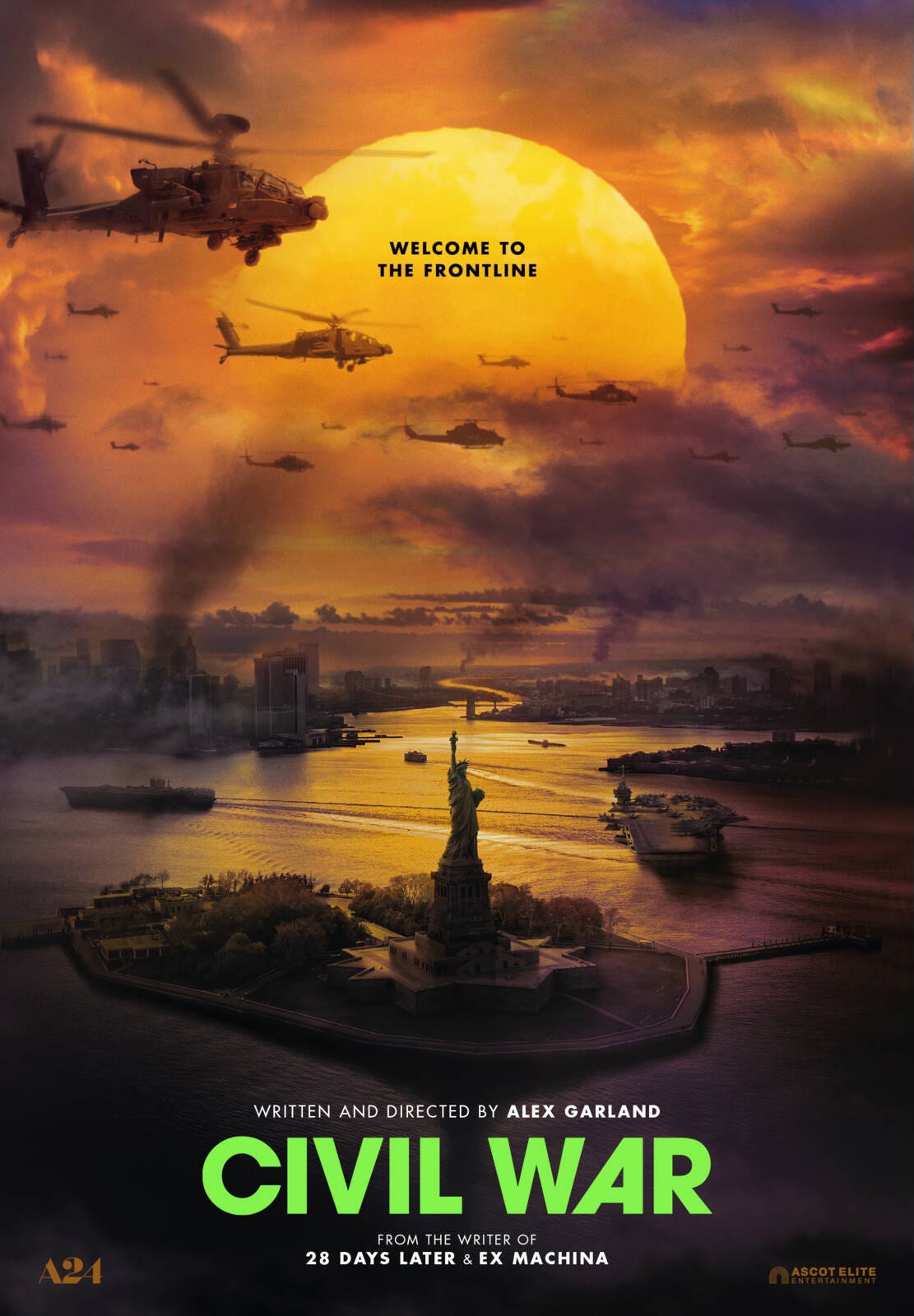

So you can see why I’ve been suffering vertigo-strength cognitive dissonance. As I travel and engage with the people around me, it’s the good old America I’ve always known … but the moment I open my phone, it feels like the cannons are about to fire on Fort Sumter.

What gives?

One possible explanation for this disjuncture is fear. Maybe people don’t put up lawn signs to avoid alienating neighbours or inviting retaliation. Maybe they aren’t showing their colours in public because they don’t want strangers haranguing them, or worse.

I don’t find that explanation compelling, however, because that just doesn’t sound like Americans. It sounds like Russians. I can tell you from experience that if a foreign journalist tries to engage a Russian in conversation in public, about anything, he’ll be met with a stone face and a quick “nyet.” Do that with Americans and they won’t stop talking. Americans afraid to bloviate? C’est impossible. “Reticent American" is an oxymoron. Monty Python nailed it with a scene in The Meaning of Life: The Grim Reaper, with a British accent, ushers an American to the afterlife, and the American, being American, insists on opining about the situation. The Reaper cuts him off. “You always talk, you Americans. You talk and you talk and say ‘let me tell you something’ and ‘I just wanna say.’ Well, you’re dead now, so shut up.”

So, no, I won’t chalk it up to timidity.

Another, more plausible explanation is simply that America’s political discourse has detached from the daily social and cultural reality of Americans.

I find that easier to accept because there is abundant evidence that American political discourse has become a carnival funhouse full of warped mirrors. The best illustration are surveys in which self-identified Republicans and Democrats are asked to describe the views of people in the other camp.

Consider the statement “properly controlled immigration can be good for America.” Democrats estimate that only about 50% of Republicans agree with that; in fact, a little more than 80% agree.

Or consider “most police officers are bad people.” Republicans estimate that less than half of Democrats disagree; in reality, 80% disagree.

What these figures show is that ordinary Republicans and Democrats both think ordinary people in the other camp are more extreme than they actually are.

That delusion is depressing but unsurprising. It gets stranger, however, when you break the numbers down to distinguish between degrees of partisan affiliation and involvement. When the NGO “More In Common” did that, it discovered that partisanship and delusion were highly correlated: The greater the political commitment, the greater the delusion.

And then there’s this astonishing fact: There was one group whose perceptions were hardly skewed at all, meaning they had a pretty good grasp of the real views of Democrats and Republicans. That group? The “politically disengaged.”

That’s right. The apathetic people who generally ignore politics were the least deluded. One reason? Apathetic people don’t follow political news. And the “More In Common” study found a strong correlation between how closely people follow the news and how deluded they are. Seriously. But there’s an important gloss on that finding. Blatantly partisan media like Breitbart, and Daily Kos were by far the worst generators of that effect, while more mainstream news had less effect, and watching old-school broadcast TV News — ABC, CBS, NBC — actually reduced delusion. Score one for the ghost of Walter Cronkite.

And here’s a special footnote for highly educated Democrats: The study found that distorted perceptions among Democrats, and only Democrats, increased in lockstep with education. So the Democrats most deluded about what Republicans think are Democrats with a post-graduate degree.

Now, with all that in mind, think about the people — ordinary folk and pundits — who are on social media constantly, tweeting up a storm, endlessly opining, churning out hot takes, expressing outrage, and urging others to join them on the ramparts. They dominate American political discourse. Who are they?

The very most extreme partisans. The people whose perceptions of those in the other camp are the most distorted.

This dangerous dynamic is amplified by the design of social media. These are private platforms that generate revenue by selling eyeballs to advertisers, so what they care about – all they care about – is grabbing and keeping those eyeballs. The extremist who enrages the other camp, and is applauded by fellow extremists, drives up engagement. That is exactly the sort of “content producer” these platforms train their algorithms to promote — while the moderate who thinks that sometimes the other side has a point, who is careful not to exaggerate, who typically addresses the substance of arguments without attacking the character or motives of those who disagree, well, the algorithms hate that guy. He doesn’t drive engagement. He is useless. Social media will never promote that guy, however thoughtful and constructive he may be. And since promotion boosts profile, and profile can be turned into money, social media creates a strong, relentless incentive to be extreme.

Remember the guy Tucker Carlson introduced to his immense audience as the best “popular historian” in America? He argued that “the chief villain” of the Second World War was not Adolf Hitler but Winston Churchill. (Because the peace-loving Hitler offered to “negotiate” peace but that warmonger Churchill turned him down. They don’t tell you that in history class, do they? No! Wake up, sheeple!) Elon Musk thought that interview was so intriguing he personally promoted it on Twitter/X to his hundreds of millions of followers. Who is that “popular historian”? I’m not going to give him any more oxygen. All you really need to know is that this third-rate David Irving was a little-known podcaster who shot to fame in 2021 thanks to a series of tweets purporting to explain that the reason why good, honest, reasonable Americans no longer trust elections wasn’t the promotion of cynicism and distrust by grifters like Donald Trump. Oh, no. It was basically because they had been betrayed and sold out by a vast left-wing conspiracy of lying, cheating elites with a family resemblance to the “Stonecutters.” So of course people are right to see fraud and conspiracy in every event they don’t like, like the outcome of the 2020 election. Naturally, those tweets went viral. Tucker Carlson loved them so much he read them on Fox News. And a star was born. That dude now has the number one Substack newsletter in the history category, with more than 130,000 subscribers, including “tens of thousands of paid subscribers.” So this is a guy who, in a few short years, went from tweeting right-wing drivel to making — a conservative estimate — more than a million dollars a year on Substack alone.

With incentives like that, is it any wonder that social media provocateurs and rage farmers are proliferating like an invasive species? Please note this is a bipartisan dynamic. The algorithms care about eyeballs, not politics, so they promote leftist extremists, too. (“Did you hear Trump’s latest outrage?! We have to stop the ReTHUGlicans! If you agree, drop me a like and a follow.”)

Similarly skewed incentives are at work in electoral politics, too.

The most important verb in American politics is “primary” — as in, “if you don’t pander to the base, you’ll be primaried.” Thanks to geographic polarization and gerrymandering, huge numbers of federal seats are a lock for the Republican or Democratic candidate. That makes the primary contest, to see who wins a party’s nomination for office, the real contest. And who votes in primaries? Typically, it’s only extreme partisans. So the best way to win a Congressional or Senate seat — often, the only way — is to be at least as extreme as the extreme partisans. And so, year after year, election after election, extremism is rewarded and moderation punished. It’s hard to imagine a better system for driving politicians and political discourse away from the centre.

And don’t forget the money! Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling striking down the sort of campaign finance restrictions that every other advanced democracy has, election campaigns have become fantastically expensive. Politicians must woo rich patrons like starving Italian artists once courted Medicis. But not just any rich guy will do. They must be both extremely rich and so obsessed with politics they’re willing to fork over seven-, eight- and nine-figure cheques. Who is that obsessed with politics? The highly committed … who are likely to be as extreme as they are committed. The politician who comes calling to that sort of person is well-advised to not pitch moderation and reasonableness.

So far I’ve been scrupulously bipartisan, but we have to acknowledge there is now a strong asymmetry at work in the two parties. The Democrats’ move to the left crested in 2020, when it was briefly cool to tweet things like #DefundThePolice and #ACAB (“all cops are bastards”) on Twitter, and insist that, yes, I meant it literally because that’s how righteous I am. Republicans have tried to portray Kamala Harris as a radical by noting, rightly, that her positions in her 2020 bid for the presidential nomination were much further to the left than now. But they ignore the obvious implication of her move back to the centre: She moderated because the middle is where most voters are in a general election — the traditional moderating force in American politics — and the Democratic Party has moderated, allowing her to make that shift. But there isn’t a scintilla of evidence for a similar shift in the Republican Party. I’ll spare you a list of Donald Trump’s increasingly radical statements and instead simply note two facts: 1) Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene said hurricanes are created and controlled by sinister forces bent on advancing their evil schemes; 2) this same wackadoodle is so popular in the Republican Party she is one of the top draws at fundraising events. Want to win office in today’s Republican Party? In much of America, you can destroy your career by being moderate and reasonable, while going ever-further to the right only has upside. That’s simply not true of the left in the Democratic Party in 2024. In fact, for all the talk of rising progressivism — even “democratic socialism” — within the Democratic Party after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was elected in 2018, moderate Democrats have mostly fared better than Democrats much further to the left in both primary and general elections.

All of this suggests an explanation for my cognitive dissonance.

The average American isn’t a hardcore Republican or Democrat. The average American doesn’t pay a lot of attention to politics. And the average American certainly is not an extremist of any sort.

The views of the average American are mostly ordinary, middle-of-the-road views. That was true 20 years ago. And 30 years ago. And further back than that. That’s true of average Americans who identify as Republicans, and it’s true of average Americans who call themselves Democrats. Distinguishing between the Rs and the Ds is hard, if not impossible — except when they talk about Republicans and Democrats. Then “affective polarization” emerges and you may hear how they don’t like those Democrats or Republicans. But if you don’t bring up politics, neither will they. And then it’s impossible to tell Democrats and Republicans apart. To this Canadian, they’re all just Americans. Friendly, talkative, hard working. Often a little clueless about the wider world. But just as often decent, generous, and reliable. I’ve always liked Americans. I still do.

Those people are the silent majority.

The term “silent majority” was popularized by Richard Nixon in 1969 to make a partisan claim. But in the mad cacophony that is American political discourse in 2024, “silent majority” is the perfect description of the countless millions of Americans whose lives and values are utterly disconnected from that bedlam.

American political discourse is to the average American what a grossly distorted funhouse mirror is to the person reflected in it. Most Americans simply aren’t like the crazies who so dominate political discourse — the crazies we foreigners constantly watch, our mouths agape.

There’s some hope in that observation.

But I don’t suggest getting carried away with optimism.

Silent majorities tend not to drive politics, especially not in times of crisis. Loud, aggressive, zealous minorities do. And in the right circumstances, even a handful of determined zealots is capable of pressing just the right nerve, at the right time, to elicit reactions that lead somewhere horrible.

One Serbian terrorist lit the fuse for the First World War. The Bolsheviks were a small minority faction within a small minority faction — a tiny minority with the chutzpah to call themselves “Bolsheviks,” meaning “majority” — yet they managed to start a civil war, win it, take command of the world’s largest country, and shape much of the 20th century around the world. In Weimar Germany, the Nazi share of the vote peaked at 37% and was falling rapidly when Hitler became chancellor.

With the right circumstances, there are more than enough zealots, cranks, and lunatics in America — very much including the once and possibly future president — to create a tornado capable of sweeping up the silent majority and depositing them in some hellish Oz.

So, no, there’s no reason to be sanguine. The cannons may indeed fire on Fort Sumter.

There is one critical difference between 2024 and 1861, however: The Civil War was fought over a conflict which could not be settled amicably. Slavery was zero sum. Sooner or later, one side or the other had to lose.

There’s nothing remotely like that today. Which would make violence, should it come, all the more tragic.

May the bedrock decency of the average American win the day.

Finally, an injection of sanity…

I don’t always agree with Dan Gardner, but this is logical, timely and intellectually comforting.

Fabulous observations. Thanks so much for the attempt to put some solid ground under the rolling cacophony.