AI and the Value of Imagination

Whether looking forward or backward, seeing reality requires imagination

I spent a chunk of this week reading and listening to people discuss AI in terms ranging from “Nirvana awaits!” to “God have mercy on us” to “we have no idea what’s coming but it’s making the ground shake.”

This Ezra Klein interview with Vox writer Kelsey Piper is excellent but long. If you’re pressed for time, this video by psychologist Gary Marcus brilliantly condenses the hopes and the fears, plus a lot of good explanation, into 16 minutes. (And don’t forget Marcus’s must-read Substack.) If you want someone to turn it up to 11 and ruin your weekend, Yuval Hariri is your guy. And finally, if you desperately want to believe everyone is overreacting in ways that will look hilarious in hindsight, here is Thomas Friedman frantically waving his hands in the air, which is reassuring because, well, you know his track record.

My personal opinion? I’m agnostic. Which is a more satisfying way of saying I’m dazed and confused like everybody else. My only strong belief about the current situation with AI is that as a writer I am uncomfortably similar to a skilled Silesian hand-weaver at the dawn of machine-weaving. Hence, my personal opinion is you should upgrade to a paid subscription before I become permanently unemployed and live out my remaining days in a cardboard box.

Pending unemployment aside, what makes this moment in history fascinating for me is that, by coincidence, I'm neck-deep in the study of how people perceived and reacted to new technologies in the past.

This moment is not, I assure you, the first time humanity has had a collective freakout over some amazing-but-scary new thing. New technologies have been giving us thrills and frights for the better part of the past two centuries.

The history of these then-new technologies isn’t well known for a prosaic reason: New technologies which excited and alarmed people in the past eventually embedded in our societies and became old technologies. Old technologies are familiar. Familiar is the opposite of amazing and scary. Familiar does not attract attention. And so these histories have faded from the collective mind.

Like any history, the histories of new technologies can be restored to memory. But it takes empathy and historical imagination to get past hindsight bias and appreciate how people were awed and shaken by the telegraph, the camera, electricity, radio, and all the rest. We all deploy empathy at least occasionally (I hope!) but historical imagination? It’s an invaluable skill that should be common. But I suspect most people seldom or never exercise it, much less get good at it, which leads them to think history is a boring list facts and not what it actually is: the rollicking record of people struggling to figure out what the hell is going on and what to do about it.

I’ll take this a step further: The imagination required to look back in time and really understand history as it was lived is the same capacity needed to look forward in time to see how things may develop. Both require the observer to appreciate how extremely contingent the path of history typically is and thus see that things could have turned out very differently (in the past) or that they have the potential to turn out very differently (in the future).

This imagination is in short supply. And that can have serious consequences.

Failing to see that the past could have turned out differently, we fail to see what made it turn out the way it did and draw false lessons from history. Failing to see that the future could turn out very differently, we do not do all we can to steer toward the future we desire and reduce or mitigate the risks of futures we fear. How many large, sophisticated organizations made grand plans for 2020 without giving a moment’s thought to pandemic risk? That was a failure of imagination.

Whenever that phrase surfaces you can be sure something has gone terribly wrong. Remember the 9/11 Commission? It was asked to investigate why so many people and agencies failed to connect the dots — there were many and they flashed red — and see the 9/11 terrorist attacks coming. After an enormous amount of research, it concluded the fundamental cause was “a failure of imagination.” I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the executive director of the commission was historian Philip Zelikow.

A lack of imagination is the root cause of what I call “temporal tunnel vision,” which constricts what we see whether we look to the past or the future. In either direction, imagination is the act of stepping outside yourself — outside your circumstances and perceptions — and seeing the world with different sets of circumstances and perceptions. Do that looking back into the past and things that appear “obvious” and “inevitable” to us in the present routinely reveal themselves to be a lot less obvious and quite evitable. (Yes, that’s a word. Where do you think “inevitable” came from?) Do that looking forward and you replace the cardboard tube we normally look through with a fish-eye lens.

But exercises of imagination bump up against what feels true intuitively. So far too many of us resist them. Serious people are far too busy, they say, to waste time imagining what might have been or what could be.

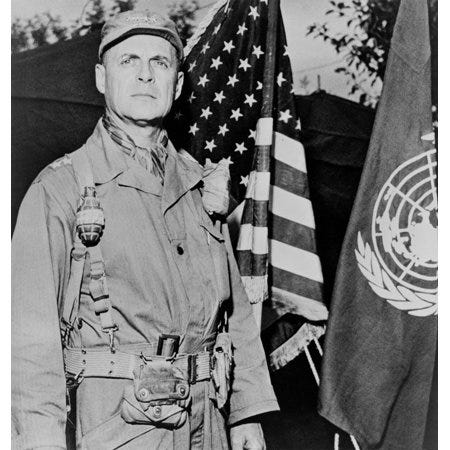

My favourite illustration of this folly is a story told by Matthew Ridgway in his autobiography.

Ridgway was a highly effective American Army general in the Second World War. He was also responsible for preventing utter catastrophe in the Korean War when the hubris of Douglas MacArthur prompted the Chinese military to swarm across the North Korean border, smashing United Nations forces in North Korea and threatening to sweep the South. (I think Ridgway’s rallying of his forces to hold the line in Korea was an American Dunkirk, one of the greatest feats in American military history, but it’s seldom highlighted because, unlike Brits, Americans don’t love a glorious defeat.)

But this story dates from a few months before the German invasion of Poland in September, 1939.

Tensions were high in Europe, but that wasn’t Ridgway’s concern, because he was posted as an operations officer (G-3) in San Francisco. The Pacific was his remit.

As G-3, in the summer of 1939 I laid on a huge command post exercise, which had as its basic assumption the fact that the Pacific fleet had been neutralized, and three invading armies were storming ashore at scattered points on the West Coast. The problem was to ascertain how quickly we could concentrate on the Western seaboard sufficient forces to turn back the invaders.

I well remember the loud criticism that broke around me when the scenario of the exercise was first announced. The assumption that the fleet had been neutralized or destroyed was fantastic, I was told. It was a possibility so improbable it did not constitute a proper basis for a maneuver.

Note that Ridgway used “fantastic” in the old sense of “fantasy.” It is criticism, not praise. Ridgway’s colleagues thought his exercise was ridiculous.

To understand how crazy that is, bear in mind that American observers had been mulling the possibility of a Pacific war with Japan ever since the rise of Japan as a modern power at the end of the 19th century, and especially since Japan’s successful sneak attack on Russia’s Pacific fleet in 1905. Ridgway’s scenario wasn’t science fiction. It wasn’t even particularly imaginative. It simply asked his officers to work through the implications of a war in the Pacific that had gone horribly wrong. And yet these officers still found Ridgway’s deviation from the status quo too fanciful to waste time on it.

Ridgway sought and received the backing of superiors, however, and he got his exercise.

We drew in from the Association of American Railroads the top traffic men in the business, some of them reserve officers, many of them civilians, who gave their time and labor in a spirit of pure patriotism. Every trainload of men and supplies was, theoretically, spotted and dispatched, through the great bottlenecks in our transcontinental rail system…. We learned a lot, we spotted many weaknesses and corrected them, and thereby saved precious hours and days when men and supplies were rolling westward of these same routes. The maneuver was held in June and July of ‘39. Two years later the Pacific fleet had been neutralized and all but destroyed, temporarily, and the lessons we had learned in our “fantastic” war game were being applied under conditions of grimmest reality.

What ominous undertones this lesson then learned has for us today. When I hear men in posts of great authority in our government, both in and out of uniform, blandly utter pontifical pronouncements as to how the next war, if it comes, will be fought, I shudder. The graveyard of history is dotted with the tombstones of nations whose leaders “knew” their enemy’s intention in war and, neglecting his “capabilities,” built their defence on that base of sand.

We simply don’t know: That’s what Ridgway is saying here. And when we don’t know, it is dangerous to proceed as if we do.

In that Ezra Klein interview, Kelsey Piper made a revealing observation. She constantly speaks with experts in the field, she noted, and there is a pattern to those conversations. The expert says “this is how I think AI will go.” She finds that scenario plausible. Another expert lays out another scenario. She find it plausible. And so on, one plausible scenario after another. This is a pretty strong hint, if any were needed, that the future of AI — what it will become, how we will use it, whether and how it will be regulated — is wide open.

And I’d add another basic point: In the history of new technologies, what the technology becomes, how people use the technology, and whether, or how, it is regulated, unfold in ways that take everybody by surprise. So even if we add together all the plausible scenarios, it’s highly likely there are other plausible futures that haven’t been imagined yet.

So what can we do with this? Not much. I told you I’m as dazed and confused as everybody else.

But I do think I can offer a heuristic for who we should listen to now and in the near future: Experts who understand and readily acknowledge how utterly wide open this moment is may be worth your time; those who see a much narrower range of possibilities are less worthwhile; those who think they have identified the singular path the future will travel are best avoided altogether.

We do not, and cannot, know what’s coming. We only know it is making the ground shake.

very astute.

Since you're basically saying that there's a whole universe of plausible opinions out there, here's my attempt:

Right now, the GPT AI(s) are basically only "thinking" in the context of answering the questions that we ask of it. So right now, the risk of any sort of AI catastrophe is low. I can't prove this, but I must admit that I'm skeptical that the AIs can "take over" without an autonomous central goal-seeking intelligence

When we start asking our AIs how to produce smarter versions of the AIs, that's the first warning bell. Because once the AIs start designing future AIs, given the statistical nature of our AI strategies, we may never really know what kind of secret capabilities they embed in their progeny.

The second (and possibly last warning bell) is when we give the AIs the robotic tools required to build smarter AIs autonomously. I'm torn on this one - on the one hand, just having robot hands isn't enough - you need power, storage, various exotic minerals, physical space, etc. At least, based on reality as we perceive it. On the other hand, once an AI has intelligence, appendages and the will to power, who knows of what it might be capable?

Thank you for this. It brings to mind the aphorism that economists have accurately predicted 12 out of the last 3 recessions.

Accurately predicting the weather up to a week in advance has become routine. The best military strategists can foresee medium term plausible scenarios and prepare for them. But no one is able to accurately predict the long term implications of any disruptive new technology.

When it comes to such predictions, my rules of thumb are (1) discount the hyperbolic pundits as they have almost always been wrong in the past, and (2) maintain humility about one's own (in)ability to predict the future. When my wife asks me what I think will happen about this or that issue, I am fond of saying, "I am not a prognosticator." It's OK to say, "This is interesting. And I have no idea how it's going to turn out."