Artificial Intelligence.

AI.

How do you feel about it? Does the very mention of those two little letters get you hyperventilating into a paper bag?

If not, you probably haven’t been reading the latest punditry.

Here is The New York Times’ Ezra Klein, in a column this week, published under the unimprovable headline of “This Changes Everything”:

I am describing not the soul of intelligence, but the texture of a world populated by ChatGPT-like programs that feel to us as though they were intelligent, and that shape or govern much of our lives. Such systems are, to a large extent, already here. But what’s coming will make them look like toys. What is hardest to appreciate in A.I. is the improvement curve.

“The broader intellectual world seems to wildly overestimate how long it will take A.I. systems to go from ‘large impact on the world’ to ‘unrecognizably transformed world,’” Paul Christiano, a key member of OpenAI who left to found the Alignment Research Center, wrote last year. “This is more likely to be years than decades, and there’s a real chance that it’s months.”

Perhaps the developers will hit a wall they do not expect. But what if they don’t?

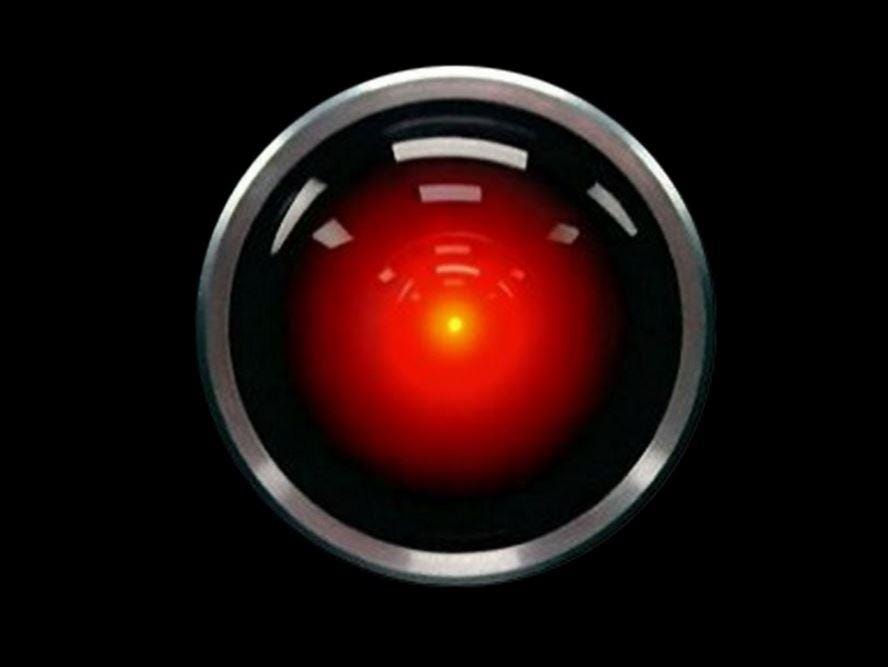

That isn’t so bad, you may think. We may be asking HAL to open the pod bay doors uncomfortably soon. But that wouldn’t be an emergency. We’re not wearing spacesuits and floating in zero gravity.

Or maybe it is that bad.

In a 2022 survey, A.I. experts were asked, “What probability do you put on human inability to control future advanced A.I. systems causing human extinction or similarly permanent and severe disempowerment of the human species?” The median reply was 10 percent.

The people working on the technology think it has a one-in-ten chance of wiping us out. That’s not good. But that means it probably won’t. Which is good. I suppose.

If you are thinking that this is the point in my column where I flip the whole thing around and explain why these fears are all hype and nonsense destined to give schoolchildren spasms of laughter when they read about them in textbooks half a century from now …

Sorry. No.

I’m as spooked as everyone else. Maybe more.

I’m a writer, remember. I feel about ChatGPT the way skilled Silesian hand-weavers felt about British machine weaving. (If you love references like that, please take out a paid subscription to this newsletter. I’m too old to retrain.) So, no, I’m not going to insist that all is for the best in this, the best of all possible worlds. (Another delightful reference! Really, you should take out a paid subscription. My dependents are awfully skinny.)

But I do have a little perspective to offer.

It isn’t reassuring in a direct sense. But it is a somewhat different way of seeing the coming storm.

It draws on history.

One of the curious aspects of AI discussions is the absence of references to the past. In part, that’s because when you see a lion rushing toward you, searching the archives for past instances of lions rushing toward people is not a course of action that comes readily to mind. But I think it’s also because people assume there is no relevant history here. This is all new technology. It has no past.

That assumption is incorrect.

The computer is at least 80 years old, measured conservatively. (This is a good timeline.) Or if we’re more adventurous, we could say it goes all the way back to Charles Babbage in the mid-19th century.

If you protest that you’re worried about AI, not computers, you should know that the term “artificial intelligence” was coined at a conference hosted by Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy in 1956. Ever since, scientists have been working on the technology and a whole lot of smart people — computer scientists, neuroscientists, psychologists, philosophers, and yes, science-fiction writers — have been wrestling what what it is, what it may become, and what it means for humanity. So even if we unwisely limit the history to that which is specifically called “AI,” it is not remotely a scary new thing. Scary, maybe. But not new. We’ve been wrestling with it for the better part of a century.

For those of us hyperventilating into paper bags, is there anything of value to be learned in that history? I think so.

Today, I’ll offer one such item.

Sometime in the next few weeks, I’ll offer another.

And maybe later, I’ll delve deeper into the history of AI. If the machines haven’t turned us into batteries in the meantime. (Administrative note: Should humanity be enslaved or exterminated in the near future, those of you who have paid for a full year’s subscription to this newsletter will not receive a refund.)

At the beginning of the 1960s, a few years after the term “artificial intelligence” was coined, a social psychologist named Robert S. Lee studied how people felt about computers.

Lee was employed by IBM, then the giant in the field. Computers were still mostly very big and expensive calculators used for highly technical jobs by highly technical people. Their role in the exciting new space program was being massively publicized, and people were duly impressed.

But few people ever personally encountered a computer, much less worked with one. That made science fiction all the more important in shaping the public mind because science fiction was quite popular and computers of all sorts were a staple of that era’s sci-fi.

Science-fiction computers were not the unglamorous calculators manufactured by IBM. They were what the authors considered extrapolations of existing computing powers: They could think like humans. But faster. Better. In science fiction, computers were often unfathomable geniuses. Sometimes they put their powers to good use (stopping the foolish humans from starting a nuclear war, for example.) But sometimes they were, to use an anachronism, the resistance-is-futile variety of artificial genius.

This was the cultural milieu in which Robert S. Lee started his research, first by conducting long interviews with 100 volunteers, then by analyzing the themes of a collection of 200 cartoons about computers. From this, he developed a list of 20 statements about computers that he put to a sample of 3,000 respondents in May, 1963. This research was finally published in an academic journal in 1970.

It as, far as I can make out, the earliest survey of its kind. (If anyone knows of anything earlier, or even in the same era, please let me know.)

These are Lee’s 20 statements about computers:

In Lee’s analysis of his data, he emphasized that while at first glance it looks like there are simply two clusters of responses, one expressing positive feeling, the other negative, he concluded it was a mistake to see them that way. The “negative” group actually contains some strong support for statements that may be seen as positive — such as “they are so amazing that they stagger your imagination.”

Instead of positive and negative, Lee defined the two clusters as a “beneficial tools of man perspective” (“Factor I”) and an “awesome thinking machine perspective” (“Factor II”).

Lee found that people who saw computers as tools — impressive tools, but no more than that — were comfortable with them and saw good things ahead.

The other group was alarmed and feared the future. But it wasn’t merely what they believed the machines were capable of (“there is no limit to what these machines can do”) that worried them. Or the consequences of those capabilities (“these machines help to create unemployment.”) It was how they did these things. As revealed in the strongest item on the list: “They can think like a human being thinks.”

Lee noted that the two clusters were not equal in size.

It should be noted that the anthropomorphic conception of the computer is clearly not the dominant one in popular thinking — at least at the conscious level as expressed in a survey statement. Typically, only a minority subscribes to the various statements which characterize Factor II, in contrast to the vast majorities who readily agree with the Factor I statements that portray the computer as a beneficial tool of man.

… Factor II appears to be an independent counter-theme in popular thought. It co-exists in the culture along with the more conventional and accepted view that sees the computer as a progressive and welcome development. It is, however, a highly symbolic and disquieting undercurrent of great emotional significance centering on the notion that the machine is autonomous and that it ‘thinks’ as humans do.

Then Lee made a powerful observation.

It has been said that the scientific revolution has resulted in a number of assaults on man’s egocentric conception of himself. Copernicus showed that our world is not the center of the universe, Darwin showed that man is part of the same evolutionary stream as animals, and Freud showed that man is not fully the master of his own mind. The findings of this study indicate that the emergence of electronic computers may be another such challenge to man’s self-concept.

Lee wrote those words in 1970, based on a 1963 survey.

Now let’s go back to that Ezra Klein column — published this week, remember — and read what I think is the most important passage:

I cannot emphasize this enough: We do not understand these systems, and it’s not clear we even can. I don’t mean that we cannot offer a high-level account of the basic functions: These are typically probabilistic algorithms trained on digital information that make predictions about the next word in a sentence, or an image in a sequence, or some other relationship between abstractions that it can statistically model. But zoom into specifics and the picture dissolves into computational static.

“If you were to print out everything the networks do between input and output, it would amount to billions of arithmetic operations,” writes Meghan O’Gieblyn in her brilliant book, “God, Human, Animal, Machine,” “an ‘explanation’ that would be impossible to understand.”

That is perhaps the weirdest thing about what we are building: The “thinking,” for lack of a better word, is utterly inhuman, but we have trained it to present as deeply human. And the more inhuman the systems get — the more billions of connections they draw and layers and parameters and nodes and computing power they acquire — the more human they seem to us.

The stakes here are material and they are social and they are metaphysical. O’Gieblyn observes that “as A.I. continues to blow past us in benchmark after benchmark of higher cognition, we quell our anxiety by insisting that what distinguishes true consciousness is emotions, perception, the ability to experience and feel: the qualities, in other words, that we share with animals.”

This is an inversion of centuries of thought, O’Gieblyn notes, in which humanity justified its own dominance by emphasizing our cognitive uniqueness. We may soon find ourselves taking metaphysical shelter in the subjective experience of consciousness: the qualities we share with animals but not, so far, with A.I. “If there were gods, they would surely be laughing their heads off at the inconsistency of our logic,” she writes.

There it is. Much the same idea as that identified by Robert S. Lee in 1963.

This is why it’s so important to not only look at AI’s output, but to look at, and really understand, how it produces that output. Is AI actually thinking, in the sense that humans think? Or is it data-crunching with near-incomprehensible speed and volume?

That may seem like the a question of interest only to computer scientists, psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers. But it should not be left to them.

If we perceive AI to be doing what it does using methods alien to us, it will still be a society-rattling challenge. Because a lot of what it does is now done by humans. And it does it better. But it should not be a threat to our very conception of who we are. (There’s some tension on this point in the comment from Meghan O’Gieblyn, above. I may unpack that in future.)

But if we think AI does what it does the way we do it, and it’s better at it than we are, what makes us special? Who are we?

That’s a crawl-into-the-fetal-position identity crisis.

If this is correct, Ezra Klein’s point that “we have trained (AI) to present as deeply human” is critical.

Read what ChatGPT writes and it’s pretty much impossible not to think it was written by an entity thinking like people think. But it wasn’t. As impressive as AI is, it is nothing like a human brain. What it does is not thinking as we think.

Companies seem determined to make AI feel as human-like as possible. I understand why. We have always humanized things to make them feel more familiar and approachable. That’s why corporations use cartoon characters and celebrities to sell products and nations use figures like Uncle Sam to embody themselves.

But I strongly suspect it’s a serious mistake to do the same with AI. Massive economic and social disruption will be plenty bad enough without a collective mental meltdown.

"But if we think AI does what it does the way we do it, and it’s better at it than we are, what makes us special?"

This really is the key thing, and it's not uncommon that new tech gets interpreted as "making people obsolete"... which is somehow never does (economists will tell you that the higher productivity of new tech creates employment with higher wages than in the jobs it displaces, which is why unemployment today is 3.5% and not 35%, despite persistently confident predictions for the past 150 years that it will be Real Soon Now.)

AI produces intelligent behaviour without consciousness. There is every reason to believe that that's extremely limited, because nature hasn't been able to produce human--or even dog--style intelligence without consciousness (and embodiment, which LLMs also lack). As I wrote last summer:

"There's been a lot of breathlessness in the press lately about machine intelligence, and how the behaviour of predictive text programs like GPT-3 implies that they are conscious.

This is very much like saying an automobile's ability to move across the ground implies it has legs, or at least feet: in nature, terrestrial locomotion is almost universally a product of something like a foot pressing against the ground, usually at the end of a leg. Even slugs and snails are of the class gastropoda, which literally means 'stomach footed'.

If you want to get terrestrial locomotion in nature, you probably need feet.

So do cars have feet?

Nope. Cars have wheels. The fact that they move across the ground implies nothing.

Artificial devices--machines--routinely emulate the behaviour of biological organisms even though they lack the features that are essential for the biological production of that behaviour.

It follows from this that intelligent behaviour is not evidence of consciousness."

https://worldofwonders.substack.com/p/the-nature-of-consciousness

Nobody sucks worse at AI than SF writers. They're writers. They either make the AI just another character (Asimov's 3-laws guys, or "Mr. Data") or a God, an imponderably wise source of all wisdom.

They really suck at spotting the capacity Edward Tufte noted when he pointed out that the human and computer are each brilliant at processing data, but in very different ways, and great synergy comes from getting them to work together in a tight loop. (That's what you see with everybody's face in their phones, getting into a tight question/answer loop.)

Replacing human intelligence is an insanely hard goal. But *partnering* with human intelligence, filling in the gaps where it sucks (crunching numbers, visualizing large amounts of data) there, we have prospered hugely. I wouldn't be researching what "AI can do" but what "People can do with tools".

When I wrote code at work that was just big SQL statements with a lot of OR and AND clauses - a sewer backflow is an actual backup, mains water going backwards to the house - IF the responder's notes contained terms like "running backward" or "depth increasing" or sixteen other popular phrases - the office staff called them the "AI programs".

I demurred, but realized that for them, it wasn't joke. That's because the programs did something, anything, that had previously required a human reader, and now could be even partially automated. If a human intelligence can be freed up, the thing that freed it is, in practical working terms, an AI.

It took dozens of those long statements to sharply raise productivity in that one little office. Over decades I did that in many offices. Others did dozens of offices, whole departments. Collectively, the utility might get by on half the staff at the end of many years of incremental development - you'd look back after 20 years and admit that the place had been, yes, "transformed".

Marketeers are wanting to sell you a product, dust their hands, proclaim you've been transformed. The real transformation will take years of integrating the AI capabilities into the still fundamentally-human analysis and decision process - and the integration must be deep, and under tight-loop human control for best results: every AI will be too stupid and clueless to do good work without tight human interaction.

The current sales pitch is the 21st equivalent to a 1969 IBM salesman slapping the top of the 1-ton mainframe and telling you that this iron genius will soon be "Running your whole office".