An Atomic Counterfactual

What if the bomb had never been invented?

Let’s start with an easy counterfactual: The time is now but nuclear weapons do not exist. What does the war in Ukraine look like?

I think there’s little question that NATO (as an alliance or its members independently) is much more heavily involved. At a minimum, NATO members are sending offensive weapons — tanks and jets — to Ukraine. But given public opinion, and the demonstrated weakness of the Russian military, I think NATO does much more than that, starting with a no-fly zone. So there’s aerial combat with the Russians. Perhaps that escalates and NATO troops are also on the ground. If so, things probably get nastier outside Ukraine — I’d want a well-stocked bomb shelter if I lived in Poland or the Baltic countries — but not for long. Russia loses this war. Quickly and badly.

But that’s first-order thinking. Let’s back up: If nuclear weapons did not exist, would Russia have invaded Ukraine at all?

I think not. Even if the horrendously poor performance of the Russian military could not have been foreseen, NATO intervention would have been seen by the Kremlin as a substantial risk. And there would have been no threat of escalation to nuclear weapons — a threat Putin has made explicitly and repeatedly — to mitigate it. So if nuclear weapons did not exist, the war in Ukraine would not have happened.

But nuclear weapons have been such a giant presence in the world since 1945 that you might think this is rather like saying, “what if gravity suddenly reversed? Would it change the war in Ukraine?“ Well, yes. But what’s the point of even thinking about it?

This is where it gets weird. And unsettling. Because unlike gravity, nuclear weapons may not be an inevitable and inescapable feature of the modern world.

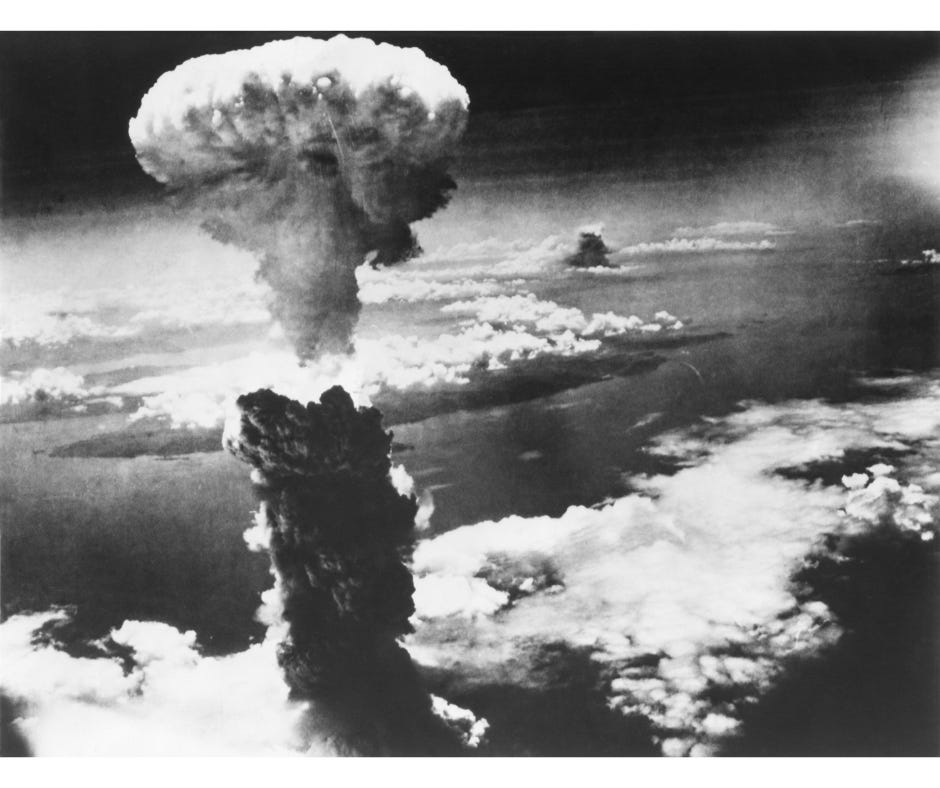

Check out this argument: 1) The successful invention of the atomic bomb in the 1940s required an almost incomprehensible expenditure of resources; 2) even if that were done, scientists were not remotely sure an atomic bomb would actually work; 3) no country but the United States could afford the resources to take this enormous gamble; 4) such a fantastically expensive, scientifically sophisticated gamble was profoundly contrary to the way the United States had always approached war in the past and was preparing to make war in the 1940s; 5) it would only have taken three or four officials to say, “that gamble is too risky, let’s put all those resources into building more tanks, ships, and planes,” to ensure the Manhattan Project never happened.

And finally, 6) if the Manhattan Project had never happened, and atomic bombs had never been proven to work during the Second World War, neither the United States nor any other country may have subsequently had the necessary combination of know-how, resources, and emergency to ever try and develop an atomic bomb.

Meaning the atomic bomb may never have been invented.

Got that? If a few American officials had not made the surprising decision to gamble massively on the Manhattan Project, nuclear weapons might never have existed.

This argument isn’t mine. I first heard it in a lecture by Philip Zelikow, an historian and diplomat who is probably best known as the executive director of the 9/11 Commission. The lecture is about “the uses of history.” It is fascinating throughout and well worth an hour and half of your time, but Zelikow unpacks his atomic argument between 3:30 and 28:35.

I find his argument — to use a term I reserve for extreme cases — mind-blowing. If Zelikow is right, it was actually quite improbable that the United States would develop the atomic bomb during the Second World War. And if it hadn’t, it is quite possible — I have no idea how to make that probability judgement more precise — no one ever would.

And modern history would be radically different. Not quite “gravity reverses” different. But close.

Watch the lecture. And be sure you are sitting down when you do.

I have often thought about this. You had many Nobel winners focused on something they would never otherwise have dreamed of doing. On the other hand, thinking of Feymann’s role, for example, the Monte Carlo simulations they ran (invented?) to figure out how to focus the primer explosion would probably be trivial today. This would be an excellent retirement project.

To add to sheer statistical unlikelihood of the Manhattan project getting off the ground, you have the baffling entry of its Secret Weapons Project lead, J. Robert Oppenheimer. I'm current listening to Malcolm Gladwell's "Outliers" (excellent so far). In a recent chapter he covered the unorthodox and seemingly self-destructive character of Oppenheimer. This man, whom we now all associate with the creation of the atomic bomb, suffered some form of mental break and tried to poison his physics professor in grad school at Cambridge. While he was there, he wanted only to focus on theoretical physics, but this same professor (his post-graduate mentor) pushed him to study more practical physics. Somehow, through charisma and societal standing, he only received minor punishment. He later had to impress Brig Gen. Groves (Manhattan Project Dir.) by having a practical first principles approach to the intersection of scientific disciplines. When interviewed for a spot on the "Secret Weapons Project team" he proposed that to create such a bomb a multi-disciplinary team of experts would need to collaborate in areas such as kinetic physics, metallurgy, material chemistry, engineering and so on. This was crucial in convincing the project director of being hired on. Gladwell quotes the book "American Prometheus" which covers Oppenheimer's life and work, which I have added to my reading list as well.