Bits and Bobs

Another collection of short notes in my futile campaign to see "bits and bobs" oust "odds and ends" as the preferred expression in North American English

Update on Gardner Enterprises

Back in April, I announced I was going to start writing PastPresentFuture full time (ish). And I was going to start a new series of articles about the history of technology which would evolve into my next book — which Crown (Penguin Random House) will publish in 2028.

I … haven’t really delivered.

For one thing, my book-related speaking — which foots the lion’s share of bills in the Gardner household — has really taken off. And given that a book about trust I co-wrote with Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia, is about to be released next month, that’s not likely to ebb any time soon.

Add in the demands of researching the next book and I’ve only managed to put a day or two each week into this Substack.

At the same time, I’ve backed off my plan to publish original research for my next book in article form here. I did that because I was stunned to see just how blatantly and shamelessly people will now steal and “repurpose” the carefully researched writing of others. There was one case in particular on Substack where a major account with a big following was shown to be doing exactly that on industrial scale. Add in the constant hoovering of everything on the Internet by AI — which again does not care to give credit where it is due — and I’m afraid the transparent and shared work process I’d envisioned for my book will lead only to theft and heartbreak.

So here's the deal: If you’ve been reading what I’ve been writing these past six months and thinking it’s worth your time, fantastic. Thanks. If you think it’s even worth your hard-earn money, bless you. But if you signed up expecting me to deliver what I outlined last April, and you’re disappointed, please do let me know. If you’re a paid subscriber, please cancel. And I’ll comp you some time to cover the months you paid. Or figure out something else. Whatever’s fair.

That said — and in the interests of transparency — I want all paid subscribers to know that the money I make on Substack now effectively covers my research costs on the next book. And no more.

In fact, I can tell you that pretty much every dollar you send me goes to exactly one beneficiary: the used bookstores of the world, which I order from constantly.

So with a paid subscription, you are simultaneously helping me write a book which I sincerely believe will be entertaining and important while supporting the used book stores that do so much to keep knowledge circulating.

I’m sure the used book stores of the world join me in saying, “thank you.”

Pete Hegseth, Crusader

Given the volume of madness generated by the Trump administration, stories come and go far too quickly for their importance to sink in. Much less be remembered.

So I want to offer a reminder of one story. And draw your attention to something that should have received much greater notice.

The story: Some years ago, Pete Hegseth, then a member of the National Guard, was flagged as a potential extremist because he had Crusader tattoos popular among both white supremacists and Christian nationalist nuts. This came to light during his confirmation process, but Republicans shrugged. Pete Hegseth was installed as Secretary of Defense — now “War” — and given command of the world’s largest and most powerful military.

What deserves more attention: Last weekend, ostensibly to honour Charlie Kirk, Hegseth produced and distributed one of the most unsettling videos I’ve ever seen.

That is Pete Hegseth reciting the Lord’s Prayer while images of American military might flash by and thrilling movie-trailer music comes to a crescendo.

The words of the Lord’s Prayer are gentle and humble. They speak of forgiveness. To set those words to images of martial pride and a soundtrack of imperial bombast is an idea so twisted it would only occur to someone with inclinations which must be described as fascist. Someone who imagines himself a Knight Templar smiting the enemies of the Lord. Someone who, in a liberal democracy, should be kept far away from power.

Perhaps even more disturbing is how little notice or controversy it stirred. It’s no mystery why. This stuff ceased to feel surprising some time ago. Indeed, as some Christians have noted with alarm, similar conflations of American military might with Christian scripture are flooding the Pentagon’s social media channels and a chest-beating, belligerent Christian nationalism is rapidly becoming the dominant tone of the Trump administration.

Somewhere, the ghost of Dwight Eisenhower weeps.

Justin Ling

Canadian readers will know Justin Ling as one of the smartest political observers in this country. But Justin also writes with great acuity about technology, extremism, and the epistemic breakdown in modern society. He even groks history and how the past is essential to understanding the present.

Justin’s latest illustrates the point nicely. It’s well worth your time. And a click on the “subscribe” button.

(An aside: I have long loved the word “grok.” I’ve used it for decades. And it absolutely pisses me off that Elon Musk has effectively appropriated it for the Fourth Reich’s AI. I think we should take it back by using it constantly. You want it? Sorry, big fella. You can’t have it. You grok me?)

“House of Dynamite”

I see Kathryn Bigelow’s new movie, House of Dynamite, will be released soon. Critics are all but unanimous that it’s wonderful. In this case, that means “terrifying” because the movie is about American national security officials who detect the launch of a single ICBM that will strike the United States in mere minutes. They have no idea who launched it. Or why. But now they must act — knowing that if they get this wrong they could spark global annihilation.

There are two versions of the trailer. This one is unsettling. But this one is truly haunting — because it features Carl Sagan delivering his Cold War-era warning about how nuclear war could snuff out life on our pale blue dot.

Netflix produced it but I’ll be standing in line to see this one at the theatre. I’m 57. I came of age at the height of the revived Cold War in the early 1980s. Fear of nuclear war was intense. In North America, The Day After terrified audiences. In Britain, Threads made The Day After look like a mildly unsettling fairy tale.

I can still see the nightmares that era inflicted on my sleep.

Of course, mine was only the latest generation to experience that fear. In 1964, the terror of the Cuban Missile Crisis produced both the black humour of Dr. Strangelove and the chillingly realistic thriller, Fail Safe. The former is much better remembered today. But Fail Safe is a stunning movie with a plot similar to that of House of Dynamite: A mechanical error causes American bombers to be ordered to attack Moscow. Efforts to recall the bombers fail. Now what? All options are horrific. I won’t spoil the ending. Let’s just say it is scarring.

Now Millennials and Gen Z will experience the feelings Gen X and Boomers know so well.

Good.

One of the basic principles of risk psychology is that if people are exposed to a danger long enough, without that danger manifesting, they will become inured. The feeling of threat will evaporate. This process can happen with any danger. Even nuclear weapons.

But nuclear weapons are designed to do one thing only, and they do it very well. No matter how locked-down and controlled nuclear weapons may, no matter how rational the leaders who control those weapons may be, no matter how much we may all passionately wish to avoid total destruction, their mere existence poses a threat that cannot be squeezed down to zero. Accidents happen. Misunderstandings occur. Miscalculations are made.

For that reason, every single nuclear warhead poses at least some risk of destruction. Maybe that risk is tiny. I hope so.

But multiply that tiny risk by the total number of warheads.

What’s the risk now? A lot bigger than it was. But maybe it’s still small. Good.

But the risk isn’t a one-off.

We encounter it this year. And next year. And the year after. We encounter it as long as nuclear weapons exist. And as every good gambler knows, even very small probabilities become certainties if you just keep rolling the dice.

We should not be inured to the risk of nuclear war. We should never be inured to it. If a once-per-generation movie shocks the hell out of people, then the directors responsible are doing us the highest service.

“Simulate and Iterate”

If you’ve read How Big Things Get Done, you’ll recognize “simulate and iterate” as the core of what Bent and I consider effective planning.

People are terrible at seeing a situation, coming up with a course of action, and implementing it successfully the first time. But people are fantastic are trying something, seeing it go splat!, learning from the experience, trying something else, learning more — and gradually developing a reliable plan. That’s “experiential learning.” Planning that does not make the most of experiential learning is bad planning.

In an ideal world, the best way to come up with a plan is clear: Just do it. See what happens. Learn from that, then do it again. Over and over and over.

To an extent, that’s how video games are “planned.” As soon as possible, you release the game so players can have at it. Bugs and others flaws are discovered. So you fix them and release again. And again. And again. The game becomes better and better over time.

But that approach isn’t possible for most of what we want to do. You can’t build a new jet, or a building, or a dam, simply in order to learn from the jet’s crash, the building’s collapse, or the dam’s bursting. It’s too expensive. And it gets people killed.

The alternative? Create a simulation — an artificial world in which you can try stuff, see what blows up, and learn.

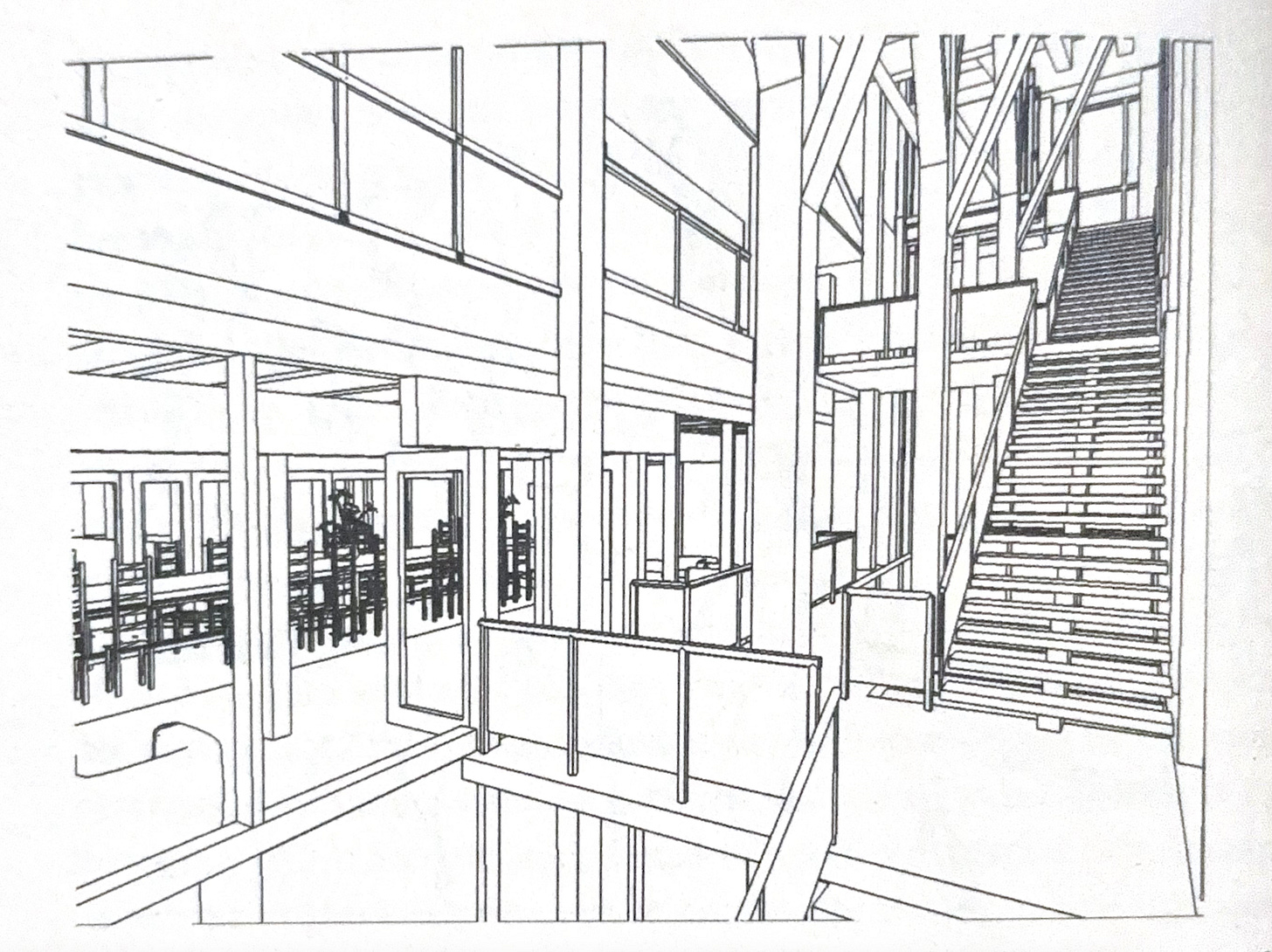

In talks, I illustrate with the story of the Bilbao Guggenheim and how Frank Gehry, in the mid-1990s, had the then-cutting edge idea of creating a digital simulation of his plan so he could really push the iterative process to exhaustion — and produce a highly reliable plan.

I have images of the resulting plan. Seen today, they looked distinctly underwhelming, for the simple reason that digital simulation has exploded over the past 30 years. What we can do now makes 1990s simulations look like cave paintings.

I recently stumble across an illustration of just that point. In 1995, Bill Gates published The Road Ahead, all about the gee-whiz tech to come. Near the end, he discusses the home he is planning to build. And the world’s richest man, this great computer genius, includes some super-cool, cutting-edge digital simulations.

Ready to be astonished?

Yeah. I know. Your mind is blown.

The fact that simulation technology has advanced spectacularly tells us something important: There’s just no good excuse anymore for plans to fail as a result of problems that could have been caught and corrected in planning. Yes, big projects will always find new ways to surprise and challenge us. But today, literally every problem that could be discovered by simulation and iteration should be.

Speaking of which: AI.

Everyone talks about how AI could be used to make final products, like commercials and movies. What fewer have noticed is that AI is already being used not to make final products but in what I think is a far more promising way: as a tool for simulation and iteration.

In the book, Bent and I discussed how Pixar developed a low-cost method of producing crude movies which they could show to audiences to get feedback they could use in the next round of iterations. Pixar would produce seven, eight, nine such crude movies before green lighting production — which usually went smoothly and swiftly because their plan was so highly tested and reliable.

Pixar’s method is cheap and reliable. But also slow and laborious.

Now add AI and it seems patently obvious that Pixar’s basic approach, with its wonderfully effective reliance on iteration, can become a lot easier and faster. Which means even more iterating. Which means even more reliable plans.

I don’t often have positive words for AI, I know, but it seems to me this is a use-case with spectacular potential in so many domains.

I am glad to in some tiny way help with funding your research. Count me in at renewal time.

Carry on soldier Gardner.