Bits and Bobs

Reverse hindsight bias, the value of civility and dumb questions, and the mother of all birthday presents

On Rosy Retrospection and Its Opposite Mistake

In The New York Times today: “Our assumption that the past was more civil is such a beautiful lie, one that serves only the people so desperately willing to believe it.”

Evidence? None cited.

This is the flip side of rosy retrospection: It is the belief that any claim of something being better in the past is wrong and therefore evidence of rosy retrospection.

As to its application here, to what “past” is the writer referring? She doesn’t say. She simply takes it as given that levels of civility do not vary, and the past could not have been more civil. Does that even pass the smell test? All those different societies and different cultures. All those different times and places. And civility is constant? Does that seem even slightly plausible?

Sorry to bang on about this point but we judge things relative to other things, which inevitably means we judge the present by the past. To do that seriously, we need to take the past seriously, to examine it, and really understand it, before judging. Otherwise we are comparing the present to our own vague impressions and prejudices — which can only lead to greater self-delusion.

And Speaking of Civility…

Again in The New York Times, Linda Greenhouse writes that the attention paid to how the justices of the US Supreme Court get along is misguided. Cordiality doesn’t matter, she writes. The court’s decisions do.

Of course she’s right, in one sense. Outside the tiny circle of the court and its intimates, any randomly selected decision is vastly more important than whether Supreme Court judges like to catch the occasional hockey game together.

But seen another way, she is wrong.

The fact that justices remain cordial despite profound professional and political differences is enormously important: It is a powerful demonstration that it is possible for people of good faith to vehemently disagree on the burning issues of the day but continue to respect each other. In a pluralistic society, that is the bedrock on which functioning institutions are built.

Look at discourse on social media. Look at politicians calling opponents “enemies.” Look at how routinely people now write off millions of those who have different views as horrible people — unprincipled, hateful, even “evil.”

So, yes, it matters that Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia — the liberal titan and the conservative giant — were friends. When respectful relationships between people with opposing views become impossible, we are lost.

In Praise of Dumb Questions

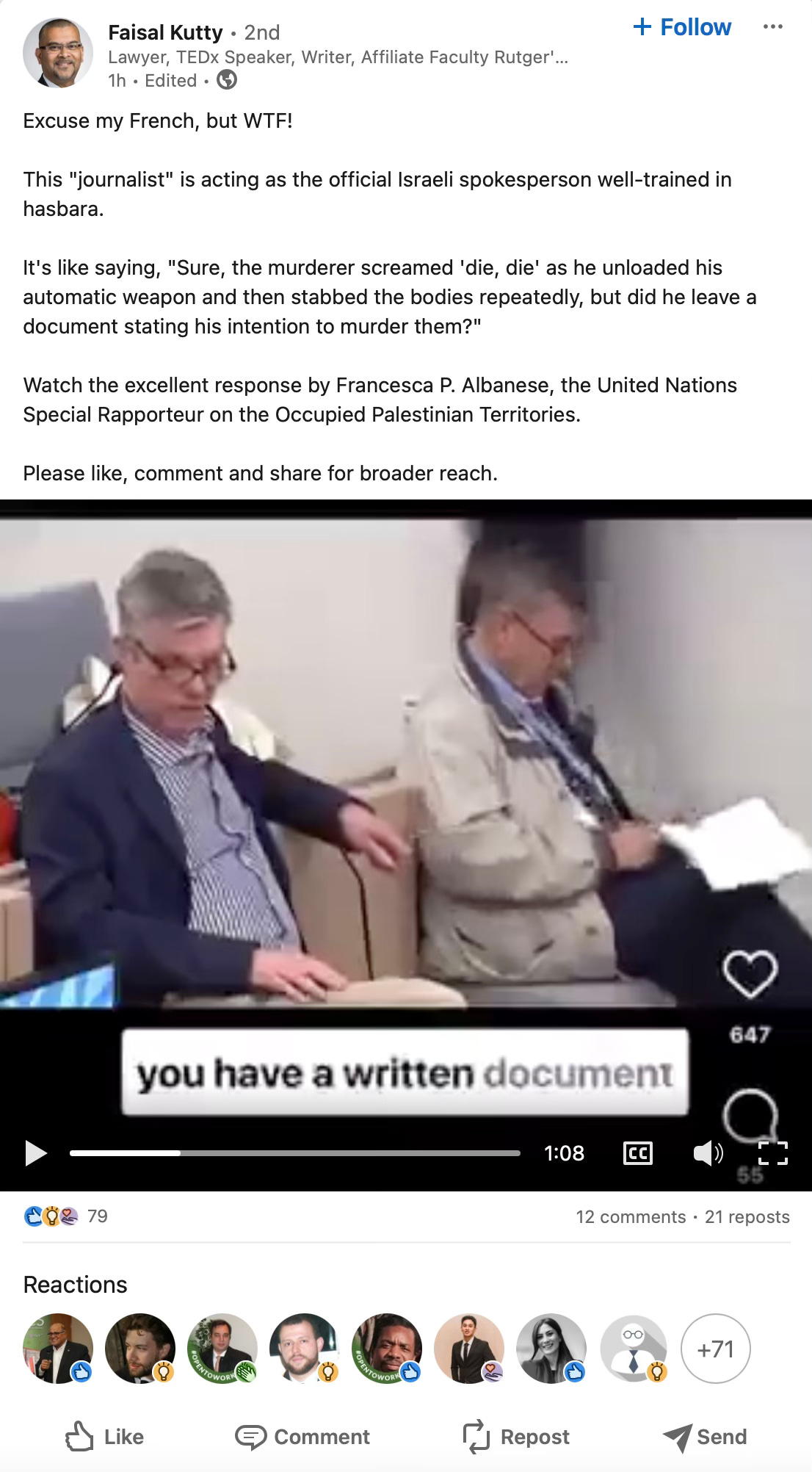

On LinkedIn, I saw something I want to discuss not because it is unusual, but because it is depressingly routine.

The post includes a video clip of a press conference about Gaza. A German journalist rather blandly says to an official — I’m paraphrasing — “you have cited instances of Israel officials saying things that you suggest show genocidal intent. These are verbal statements. Do you have any such statements in written documents?” The official responds with a long statement in which she scorns the journalist for asking such a silly question, notes that in past genocides those responsible avoided creating such documentation, and restates her case with considerable verve.

What’s fascinating to me is the reaction below, and the vast number of comments left on it.

One person after another lined up to do two things: One, they accused the journalist of every imaginable sin in the most ferocious language; two, they praised the official’s response, which they considered brilliant and something to be shared far and wide.

Not one person recognized that the official would never have delivered the answer they loved if the journalist had not asked the question they hated.

Journalists ask question for many reasons.

Often, it’s an attempt to confirm something that seems obvious but it must be confirmed, not assumed, before being reported as fact. That’s Journalism 101. Journalists who don’t do that are not worthy of the name.

Other times, a journalist will ask a question not because the journalist doesn’t know the answer but because the journalist’s readers may ask that question. That, too, is Journalism 101. It is doing the work your reader needs you to do.

Or a journalist will ask a more pointed question because that is an argument being made by other relevant parties. The longer way to make the point may be: “Mr. Jones says it was your idea to leave the flaming bag of feces at the front door of the deceased. How do you respond to that?” The shorter: “Was it your idea?” Asking the question is not making an argument. It is a way of exploring arguments.

Journalists do sometimes ask certain questions because they have ideological axes to grind. Or they’re ignorant. Or they’re stupid. Or they just want to rile people up and get a good clip for YouTube. All of this has always been true. But it is increasingly true, I think, in this brave new world in which we find ourselves — a world in which straight news reporters are an endangered species while carnival barkers calling themselves “journalists,” people like Tucker Carlson, proliferate like zebra mussels.

This is all fairly obvious, no? And yet, with clock-like predictability, most people assume that when a journalist asks a question which does not support their perceptions and beliefs, that journalist must be motivated by axe-grinding, or ignorance, or something else that reflects badly on the journalist. And they never — I mean never — credit the questioner when the respondent delivers what they consider a magnificent reply.

Which I will never cease to find amazing. Have these people never seen Columbo?

We learn by exploring. And the most powerful way to explore is to ask questions. Lots of questions. Even “dumb” questions. Especially dumb questions.

In How Big Things Get Done (it’s been ages since I plugged my book so grant me this indulgence) Bent and I have a chapter on “asking why?” Sticking perceptions together into a quick-and-easy understanding of reality is absolutely effortless. The brain does it automatically. Compulsively. What’s hard is not allowing yourself to be fooled into thinking that your quick-and-easy understanding is fully informed and accurate. What’s hard is asking “dumb” questions.

And yet, if there’s one thing I’ve learned in decades of asking questions, smart and dumb alike, it is that dumb questions are far more probative than the supposedly clever questions that impress others.

In our book, we zero in on Frank Gehry, the legendary architect. Whenever a potential client comes to Gehry, he pulls a Columbo: He sets aside what is “obviously” true and peppers the client with questions about why the client wants to do this project at all. To an external observer, this may seem simple-minded, even naive. It’s just the opposite. Gehry’s questions often reveal goals clients do not express easily or immediately, goals they may not even be entirely aware of themselves. I cannot overstate how important this questioning is to the success of such projects. You know the Bilbao Guggenheim? One of the world’s most famous buildings? And one of the world’s most successful major projects? It wouldn’t exist without it.

The ultimate illustration of the power of dumb questions, however, can be found in any conversation with a four-year-old. They ask “why?” again and again and again. It can drive a parent mad. Not only is it exhausting, it forces us to push beyond assumptions and really explore the limits of our knowledge. And we rapidly discover we know less than we think. This is why “the five whys” is such a powerful technique for exploring root causes and really understanding what’s happening — as opposed to merely being satisfied with the feeling that you understand.

Yes, questions are often asked in bad faith, but assuming bad faith is the lowest and laziest habit of the Internet Age. The wise person starts by assuming good faith. And questions asked in good faith — even the dumbest of dumb questions — are the best tool we have for sweeping aside bias and prejudice and really understanding reality.

I ask a lot of dumb questions, a fact of which I am personally and professionally proud.

My Birthday

Monday, April 8, was my birthday, so I celebrated by hosting a solar eclipse. It mostly went off without a hitch. The excellent weather I ordered was duly delivered the day before and it held through most of the following day, as requested. Unfortunately, I will have to have a word with someone because while clouds covered the sky for only two of the 48 hours on Sunday and Monday, they were the two of the solar eclipse.

I should also note that I was at my cottage because I had learned via a website that the hamlet nearest me — it’s a gas station and a house, so calling it a “hamlet” is generous — would be within the narrow zone of totality. Only after getting to the cottage and using an app with GPS did I discover that my cottage was itself just north of the zone. Three miles north, to be precise. This matters because the effect of a solar eclipse is not linear: For an observer on earth, covering 99.9% of the sun produces quite a different effect than 100% coverage.

I’ll also have to have a word with my party planners.

But silk purses and all that, when the glorious moment of shadow approached, I sent up my drone to create a time lapse video, if not of the disappearing sun, then the ensuing darkness at my lake. Here is a link to that video. (I hope you can access it. Tech ain’t my thing.)

https://share.icloud.com/photos/008NR4FLTDc9faZbC8iFiYpDQ

I think what I see in that video — and experienced firsthand — is something I find pretty amazing: It is the border of the zone of totality, demarcated with light.

But I may be making unwarranted assumptions. If there are any astronomers among you, please clue me in: Does that video show what I think it shows?

Dumb question: do I need to wear a welding helmet to safely watch these videos?

I don't know if your video shows that line, but it seems quite possible. Here's a video I took from(I think) within the zone of totality. The shadow moves differently, and seems to cover the sky and land more completely.

https://x.com/TweetsCoffman/status/1779156749217337465