The title and sub-title above are what I usually use for a post consisting of a series of discrete items. But because “bits and bobs” is a Britishism, while “bit and pieces” is American, there’s something meta about it today.

We’re all living in Amerika.

Twenty years ago, the German metal band Rammstein released Amerika.

It’s an angry denunciation of American cultural dominance with provocatively bilingual lyrics like this:

We're all living in Amerika

Amerika ist wunderbar

We're all living in Amerika

Amerika, Amerika

We're all living in Amerika

Coca-Cola, Wonderbra

We're all living in Amerika

Amerika, Amerika

This is not a love song

This is not a love song

I don't sing my mother tongue

No, this is not a love song

When Amerika was released in 2004, American political, economic, military, and cultural dominance was at what we would later realize was its zenith. People still talked about the United States as having ascended from mere “superpower” status to “hyperpower.”

Twenty years later, we live in a different world.

Starting with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the United States — both government and people — made a series of catastrophic mistakes that eroded American dominance along multiple axes. Couple that with the rise of an increasingly nationalistic and aggressive China and no one calls the United States a “hyperpower” any more. At least not in political, economic, and military terms.

Look at Google Trends:

But what about culturally? Has American dominance similarly declined?

That’s a huge question I can’t seriously tackle here but I very much doubt it. Consider the murder of George Floyd.

I don’t have to tell you who George Floyd was. I don’t have to tell you what happened to him. Or the consequences. You know all that.

You may live in the United States, Canada, or the United Kingdom.

You may be Australian, German, Japanese, Brazilian, Korean, Italian, Swedish, or South African.

It doesn’t matter. We all know all about George Floyd.

Pause a moment and think about how strange that is.

George Floyd was an ordinary man murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It’s understandable that his murder was national news in the United States. And it’s no mystery why it sparked so much unrest and soul-searching across America.

But why do hundreds of millions of foreigners — I’ll be conservative with that number — know as much about Floyd and his murder and its consequences as Americans? Why did they hold their own protests? Why were so many of the consequences of those protests similar, from toppled statues to investigations of racism?

The history of race in America is unique. Policing in America is unique. The social ills that continue to plague black Americans are, in combination and degree, unique. Yet billions of foreigners followed the news from the United States closely and many were inspired by it to carry out actions very similar to those carried out by Americans responding to this most American of crises.

I suppose you could argue that’s because racism is global phenomena and people connected the dots. I think that’s a mighty stretch that belittles how unusual America’s history with race and racism really is, and how different the current realities of black people in America are from blacks elsewhere.

And it ignores a much simpler explanation:

We’re all living in Amerika.

We are constantly immersed in American news, television, and movies. That was true for much of the 20th century but the Internet, and social media in particular, have made that all the more true. American cultural dominance of our mental environments is so ubiquitous we don’t even notice it. We’re like fish swimming in water.

Doubt that? After the George Floyd murder, Black Lives Matter protestors in London chanted “hands up, don’t shoot,” a slogan first used in protests following the murder of a black man in St. Louis in 2014. And that was a little odd because British police don’t carry guns.

Here’s another illustration: Who is Marjorie Taylor Greene?

American or Canadian, German or Japanese, Brazilian or South African. If you’re plugged into the great global electronic brain anywhere on the planet, you know the answer.

But Greene is a minor American legislator.

Can you name a minor French legislator? Any minor French legislator? A minor Japanese or British legislator? If you’re not French or Japanese or British, of course you cannot. Why would you?

But billions of people all over the world know who Marjorie Taylor Greene is.

We’re all living in Amerika.

When some spectacular and awful crime is committed in other countries, the foreign media dutifully report it, briefly, and that’s the end of it, which is perfectly reasonable for an event of no significance to foreigners. But when the latest slaughter happens in the United States, it dominates global headlines, and the horror Americans feel is felt by billions all over the world.

Consider that after every mass shooting, foreigners take to Twitter to passionately insist America needs gun control. And no one ever remarks how bizarre that is.

Or consider abortion. Every educated person in the developed world knows what Roe v. Wade is. They know that the US Supreme Court recently struck it down. And when the court issued the latter decision, countless foreigners — even politicians! — took to social media to passionately express their feelings, just as countless Americans did.

We’re all living in Amerika.

If this were simply a matter of foreigners wasting mental bandwidth on matters that have little to do with them it wouldn’t matter. But America’s cultural dominance is so overwhelming that it surely encourages foreigners to think that American realities — or at least their perceptions of American realities — are the realities of their own countries. And that can have real consequences.

I’m Canadian. I see this dynamic constantly. Over the last 20 years, for example, the impetus for new gun policies has often been shocking events in the United States — even though Canadian gun laws, gun crime, and gun culture have been radically different since at least the 1970s.

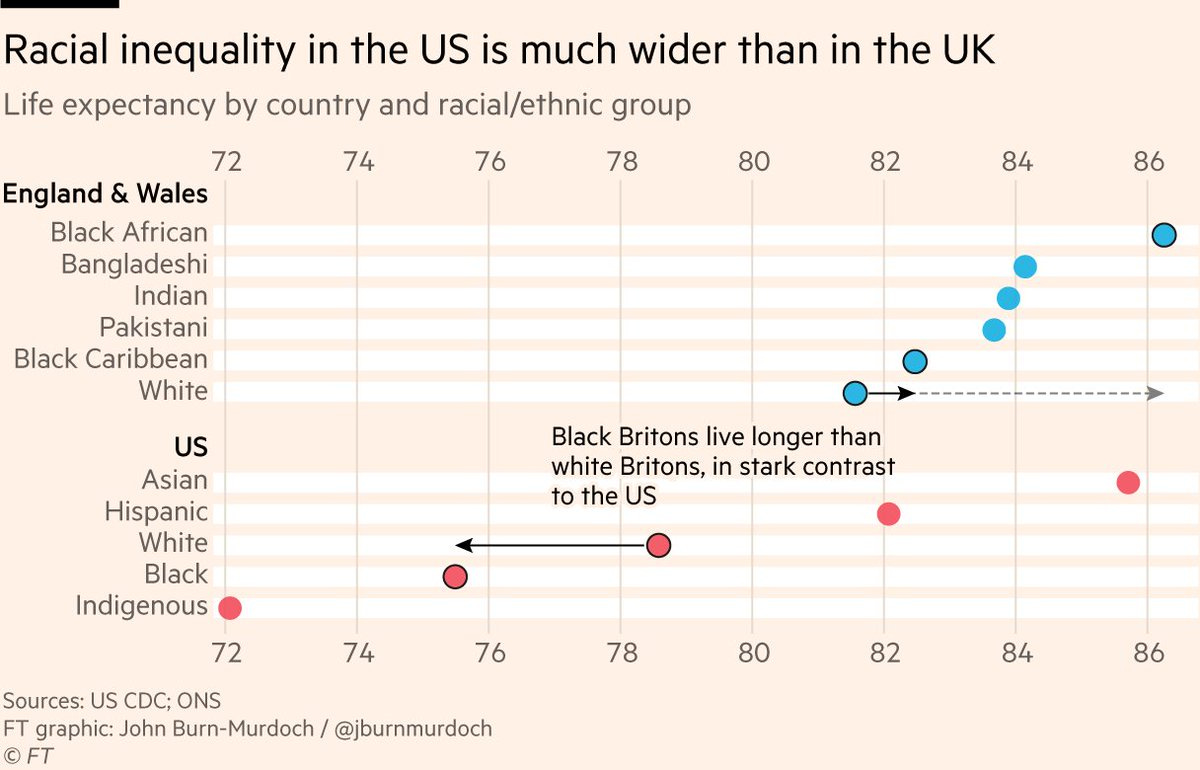

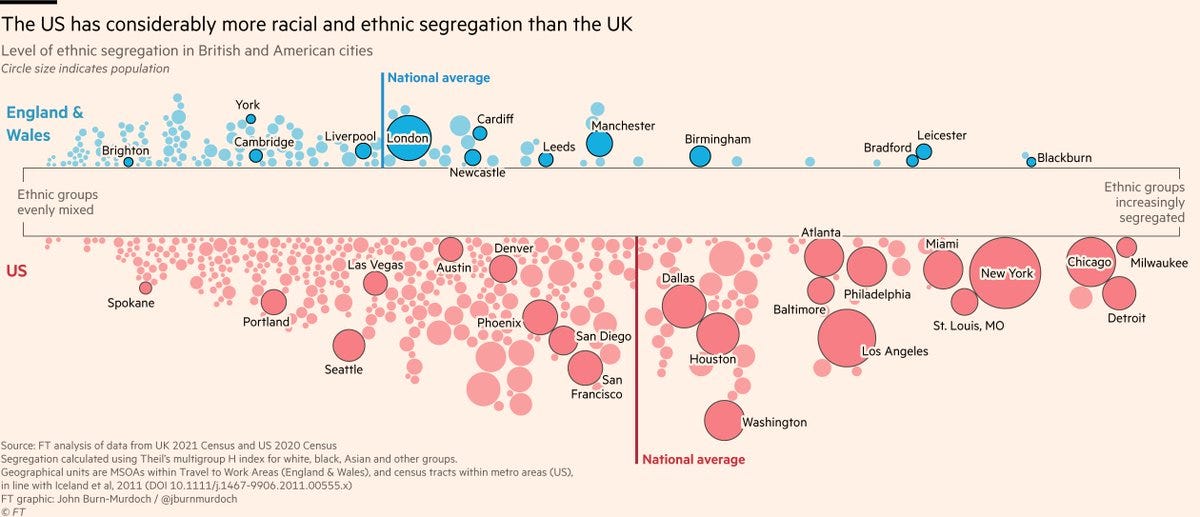

The false perception that American reality is British reality is a favourite target of John Burn-Murdoch, the superb chief data reporter for the Financial Times. In a recent thread, he laid out some statistics. Here are a few. (Read the whole thread. It’s astonishing.)

How many Brits know that the life expectancy of black Britons is higher than that of white Britons? I suspect it’s quite low. In fact, I’d bet a large amount of money that much of the population thinks the reverse is true — because it is in America — and they would be stunned to learn the truth.

Yet the histories of black people in the United States and black people in Britain are radically different. It shouldn’t be a surprise that their current realities are different. It should be the default assumption.

But that’s not how we think today. Because we’re all living in Amerika.

The history of absolutely freaking everything.

Something I love about Substack is the diversity.

There are lots of big-name writers, like Matt Yglesias, who do the sort of writing here they formerly did elsewhere. They are lots more little-known writers doing the same. There are also writers like me, who use Substack idiosyncratically, shall we say. (Idiosyncratic: from the Latin for “whatever odd little idea burbles up.”)

There are also a few using Substack much more ambitiously.

Take David Roman. He’s a former Wall Street Journal reporter who decided it would be “fun” to write a “long, detailed, single-author history of mankind.” Yes, “fun.” He actually wrote that.

Roman’s been at it for two decades, so although he hasn’t quite written everything about everything, he has completed acres of writing. Which he has brought to Substack, where he regularly adds to it. And because the history of the whole damned species isn’t enough, he also has a forthcoming book comparing Chinese and Western philosophy.

As you can imagine, laying this all out gets a bit complicated. Here’s the piece he wrote explaining how to navigate his magnum opus.

WYSIATI is a warning, not advice.

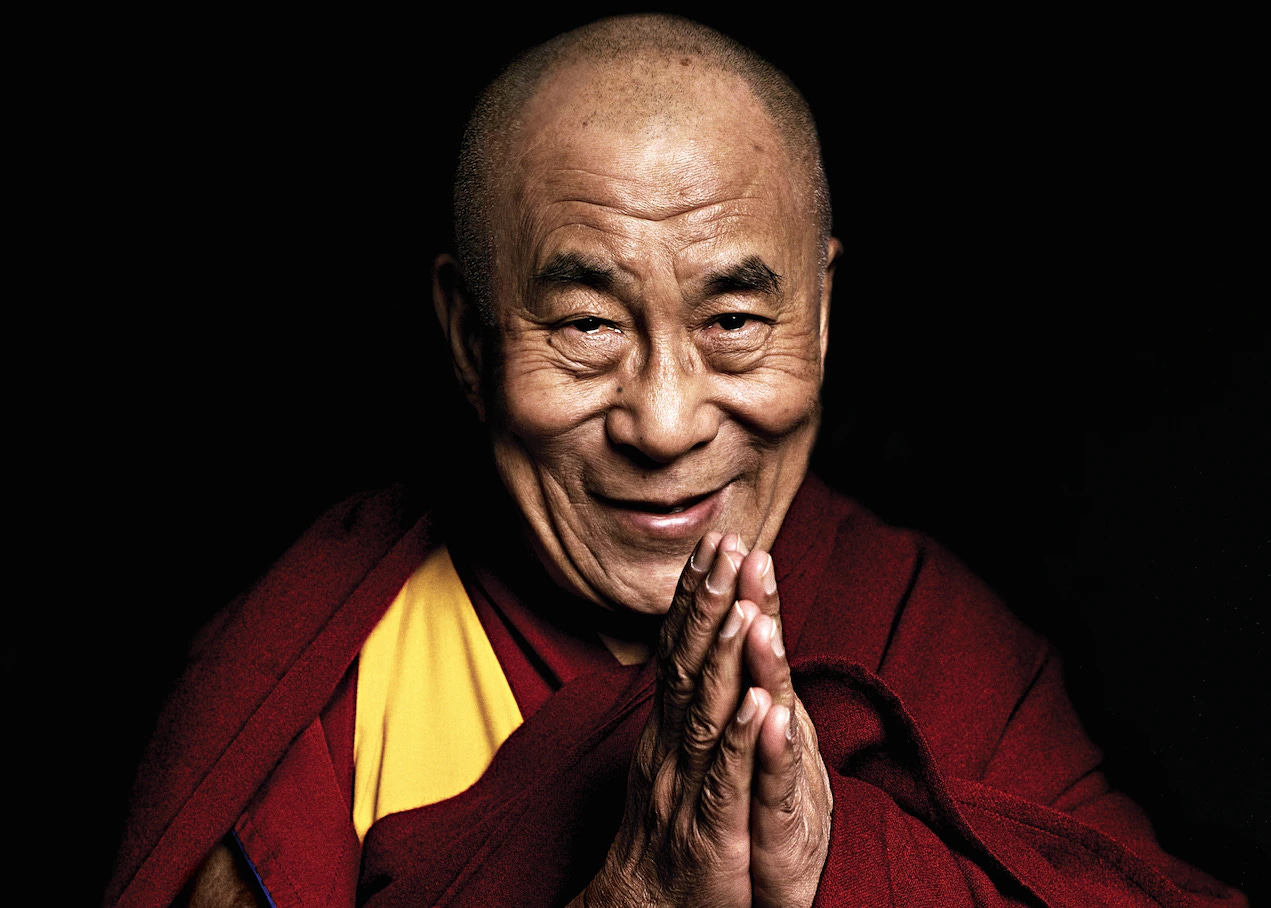

Picture this scene: An elderly man says to a young boy, “suck my tongue,” sticks out the tongue in question and laughs. The boy approaches and the man gently bumps his forehead against the boy’s. He gives the boy a small kiss on the lips.

If you are like most people, in most cultures, you now have — to use the technical term — the creeps.

So it’s no surprise that when this scene played out in front of a large audience and television cameras, with the Dalai Lama playing the role of the creepy old man, the video went viral. That was back in March. It has been seen by countless people. It’s still making the rounds on social media — and people are still reacting the way the vast majority reacted in March, with disgust and anger. Uncountable millions outright accused the venerable monk of being a pedophile, or silently suspected it.

That is also no surprise. It is foolish in the extreme. But not surprising. At least not if we bear in mind “WYSIATI” — What You See Is All There Is — the acronym coined by the Nobel Prize-winning psychologists Daniel Kahneman.

As Tibetans were quick to explain to any reporter who would listen, everything the Dalai Lama did was entirely innocent in the context of Tibetan culture. Greeting others by sticking out the tongue is common. Touching foreheads and noses and kissing on the lips are ordinary displays of chaste affection. As for “suck my tongue,” elderly Tibetans traditionally tell young children they’ve given them all their love and everything they have so all that’s left is their tongue — which they are invited to “eat.” The Dalai Lama was speaking in his poor English, which probably explains how it became “suck.”

But few people waited to hear that explanation before expressing dismay and condemning an honourable man. For that, we can thank WYSIATI.

Kahneman famously called the intuitive mind “a machine for jumping to conclusions.” The purpose of that machine is to deliver quickly. Confronted by snakes or lions, or a fellow human with a large club, our ancient ancestors couldn’t patiently look for relevant evidence, think about it all carefully, and decide whether the threat was imminent. They had to make a snap judgment. And the only way to make such a judgment is to treat whatever information you happen to have at this moment as the only information.

In other words, What You See Is All There Is.

We all know the danger of “jumping to conclusions.” We tell our children not to do it. But the unsettling truth is we all do it, every day, without a moment’s hesitation.

This hypocrisy is sustained by our failure to recognize what we are doing. Conclusions made this way don’t feel premature or barely considered. We don’t feel we jumped to a conclusion. In fact, we would be offended by the suggestion. We made the only reasonable judgment possible given the evidence. The conclusion is simply true.

So if an old man asks a child to “suck my tongue” then gives the boy a kiss on the lips, we instantly conclude it is sexual and deeply inappropriate. Period. We do not think, “based on the information available to me now, the only explanation for what I am seeing is that this man is creepy — but it is possible there may be information I am not aware of that, if known, may suggest different explanations.” Living in environments where hesitation can mean death, thinking like that can turn you into lion food. So we look, judge, and are certain we know the truth: “The Dalai Lama is a creepy old pedophile,” we type disgustedly. Then hit “tweet.”

I was the subject of a Twitter pile-on once thanks to exactly this dynamic.

Several years ago, Jordan Peterson said something to a New York Times reporter which I thought was obviously ambiguous. Read one way, it was horrifyingly sexist. Read another, it was bland and barely controversial. The reporter treated the statement as if it could only have the horrifyingly sexist meaning. So did the millions of people who find Peterson appalling. Twitter swelled with furious condemnations. (I’ll keep this vague because what he said isn’t the point here and I don’t want to go down a Jordan Peterson rabbit hole. If you must know, I find both the love and the hate for the man to be mystifying. How can anyone love or hate someone so silly, banal, and hilariously pompous?)

I tweeted something like “his statement was ambiguous so we really should clarify what he meant before we pillory him.” For the next three days, something like 10,000 people took time out of their busy days to tell me there was no ambiguity, I was clearly a woman-hating Peterson fanboy, probably a Nazi, and by the way, I really should die already. It was a curious experience. Rather like jumping off a cliff in a squirrel suit. Or so I imagine, as I have never jumped off a cliff in a squirrel suit and, having experienced a Twitter pile-on, never will.

Then Peterson told reporters that he had meant the bland and barely controversial meaning. The hate-tweets kept rolling in.

The same goes for the Dalai Lama. He made a quick apology but that seems to have been taken by the mob as an admission of guilt that brought out still more pitchforks and torches. The explanations offered by Tibetans were swept away in the roar of the storm.

This isn’t complicated. Or at least it shouldn’t be. Contrary to what evolution has wired us to believe, in this big, messy world, there is almost always another possible explanation, even if we have no clue what it is. Could anyone who didn’t know about the obscure Tibetan custom involving old folks, children, and tongues, have imagined such a thing? I doubt it. But if you have spent some time on this planet, you should know that there is always more you and I don’t know, that what you see is not all there is, and quick conclusions that are “obviously” true may very well be wrong.

Putting an asterisk on all our conclusions, learning more, and being prepared to revise any of them in light of new evidence, is the hallmark of those members of our species who appreciate the fallibility of what evolution has wrought in our craniums. For the rest, the hallmark is raising a pitchfork and joining the howling mob.

The incident with the Dalai Lama suggests the latter still outnumber the former by a depressingly large margin.

The Blank Slate, revisited

While I’m on the subject of saying things that shouldn’t be incendiary but somehow are, Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate, a book that grabbed me by the lapels and shook me hard, is now twenty years old. In this lengthy interview with Razib Khan, the inimitable Pinker gives a good overview of the book, its reception, and what has gotten better and worse — mostly worse — in the intellectual climate over the past two decades. And it’s all delivered with Pinker’s usual breathtaking verbal clarity. (Transcribe the speech of even an unusually articulate person and it’s pretty choppy on paper. Pinker’s reads like it’s been through five drafts, two editors, and a proof reader. How does he do that?!)

This is an absolutely lovely piece. I was thinking it was likely that the Dalai Lama thing was going to have an OK explanation but I hadn't googled around to find out what it was ... and for that alone I need to thank you for writing this.

I feel like we need a term for this ability to see the "obvious" conclusion and yet at the same time to doubt that it is the end of the story. I don't remember who coined it, but the term "bullshit detector" is pretty good. Everyone needs one of those, and some people have much better detectors than others.

A different term that I like very much is "moral imagination."

Reading books, especially great books from or about other epochs, is a way of expanding our moral imagination. It's no surprise to me that someone with as deep an interest in history as yourself would be good at processing news without jumping to the worst conclusions. I've never been a big history reader but I have read many novels from other time periods and other cultures, as well as philosophy and theology from down through the ages, and those are the resources that come into play - automatically, it seems - as my bullshit detector goes beep beep beep at the latest stupid internet pile-on.

Another great piece. Reinforces my belief that learning the fundamentals of CBT (jumping to conclusions being one of the classic cognitive distortions) could have broad benefits beyond mitigating specific mental health issues and perhaps should be taught starting in elementary school.

I also think there’s something to the reverse CBT theory as written up by Haidt and Lukianoff (and Yglesias)…

https://www.thefp.com/p/why-the-mental-health-of-liberal