Bits and Bobs

The speed of news, Dennett, cancel culture, Andreesen, no more "grifters," the uncertainty illusion, and a little shameless bragging.

Please, news media. Slow down.

Speed has always been prized in the delivery of news.

After the Battle of Waterloo, fought on a Sunday, the Duke of Wellington dawdled a little — a man’s got to relax after defeating Napoleon — then he wrote an account of the clash that determined the fate of Europe. This was handed to Major Henry Percy of the 14th Light Dragoons on Monday afternoon. Percy rode off madly to the coast. Light winds becalmed the ship carrying him across the English Channel, so he lowered a row boat, put two captured French eagle standards at the bottom, and rowed furiously. In England, he commandeered a carriage and horses and raced on with much cracking of whips.

In London, news had arrived that the French and British armies were about to meet. But there was no news of the outcome that, by then, had surely been decided. A whole nation held its breath and waited. And waited. And waited.

Percy roared in and the city went wild. It was past 11 PM on Wednesday.

In news, speed matters. It always has. It always will.

But the world today has radically changed, and not only relative to the world as Wellington knew it. It is astonishingly different even from the world of Bill Clinton playing his saxophone on Arsenio Hall’s show. (“Arsenio who?” Ask your parents, kids.)

Back in the Clinton era (I feel so old writing that) newspaper and television reporters constantly hurried to meet evening deadlines. At a minimum, they had to be as fast as their competition. But that wasn’t the goal. The goal was to be first to deliver news — the first to roar in like Major Percy, announcing that Little Boney had been thrashed. That was the crowning glory.

Reporters found the pace of this relentless treadmill hard to maintain. So did anyone who had to keep up with the daily news cycle, as any politician of the era will remember.

But that was almost 30 years ago. Today, we all have phones in our pockets, and social media, and push alerts. To today’s reporters, the phrase “daily news cycle” sounds as pleasantly slow and thoughtful as Thomas Jefferson scratching out a letter by candlelight and handing it to a rider to be delivered to John Adams.

The speed of news is now as fast as a human can type and light can zip through fibre optics. Soon, human fingers will be withdrawn from that production process. The dizzying speed of news will accelerate again.

And that is horrible.

Information flow is good, generally, and faster information flow is better than slower. To a point. The human brain can only process information at a certain speed, in a certain volume, and if by “process” we mean “can reasonably understand, and accurately judge, and make use of” — then that speed is considerably slower than what our technology now enables.

Which brings me to this travesty.

When The New York Times published this online — and The Times was far from the only major news outlet to make this mistake — we knew almost nothing about this event other than what Hamas claimed. That headline and caption are wildly irresponsible. The phrasing is dangerously ambiguous (a reader could reasonably conclude that it was a fact, substantiated by The New York Times, that Israel struck the hospital, with the “Palestinians say” referring only to the death toll.) But more to the point, The Times knew almost nothing! This was not the time to report anything. This was the time to make phone calls and learn more.

Any decent reporter would know that. Hell, any mediocre reporter would know that. And this is The New York Times! They hire the best of the best.

With perfect predictability, countless online commentators took this as proof of the Times’ nefarious political agenda. Maybe it was. Without further investigation, I can’t rule that out. But I know there is a much simpler explanation. An explanation with bigger implications.

Some gnome at the Times pressed “publish” on this because the gnome felt there wasn’t time to ask other editors to take a look. There wasn’t time to have a discussion about what this says, and whether it accurately reflects the facts as known as the time, or even whether there were enough facts to report anything. There wasn’t time.

Because the gnomes are under intense pressure to be first.

So the gnome pressed “publish” on a package that a little reflection would have revealed was not remotely ready to be published. With predictable results: Israel said it wasn’t responsible, US intelligence agencies concluded it was probably an errant rocket launched from within Gaza, the rocket actually hit a parking lot next to the hospital, the real death toll seems to be far lower… Yeah. That’s what happens when you report on an event you know almost nothing about.

(Are you wondering why there’s a photo of a demolished building if the rocket actually hit an adjacent parking lot, not the hospital itself? Look closely at the photo caption. That’s not the hospital. It’s a building elsewhere. Which you won’t grasp unless you read with the sort of extreme care no normal news reader uses.)

The speed of news has become unsustainable. It makes reporters and editors do stupid things like publish unverified allegations from one party to a conflict. And that can do terrible damage.

This fiasco has damaged The Times’ reputation for professionalism with countless readers. Some see a political agenda. More see incompetence.

Either way, it’s poison. Because speed isn’t the only thing that matters in news. In fact, it’s not even the most important thing.

The thing that matters the most — what towers over all others — is trust.

If people trust The New York Times to properly vet information and only report what they are confident is true, The New York Times can thrive. If they do not trust The Times — if they do not say, “it must be true, I read it in The New York Times” — it’s over.

Trust is the foundation of the news business. Destroy that and it all collapses.

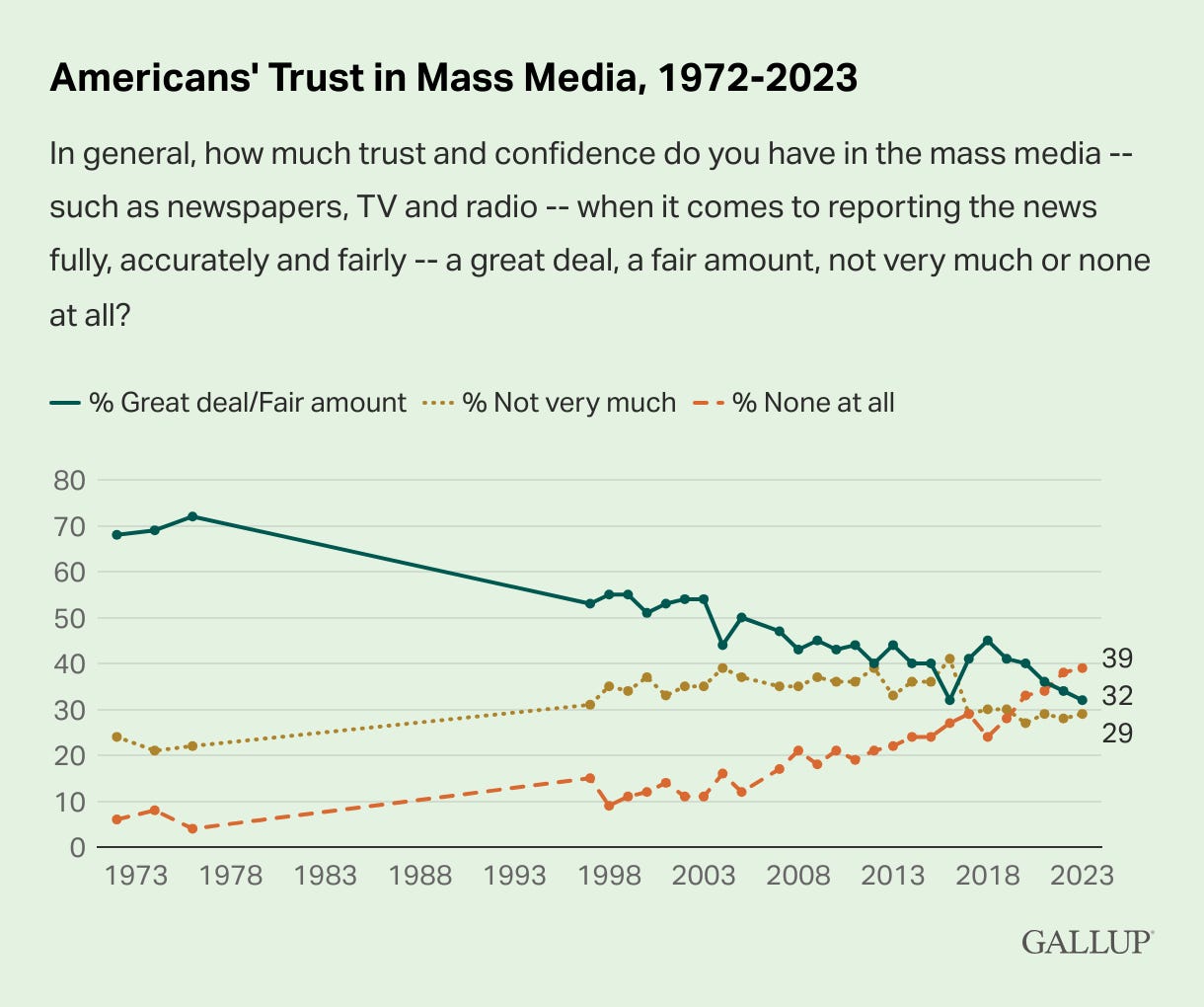

That foundation is crumbling. Take a look at Gallup’s just-released poll on trust in the American news media.

An important element of maintaining trust is being open and straightforward about your failures and explaining how you intend to do better in future.

So how did The Times respond to this latest round of folly? With this story:

“Mistakes were made. By some. But they weren’t really mistakes. It’s hard, you know? Don’t blame us.”

Does that restore your trust?

Faster has always been better in the news business. No more. News is now moving at dangerous speeds — speeds that outstrip the ability of humans to make sense of what’s happening and ensure that only facts are reported.

For the first time in history, news reporting needs to slow down.

Take the extra time to question, to investigate, to verify. Or keep cutting your collective throat. That’s the choice the news media are facing.

That sounds a little grim but I think there’s also an opportunity here, for those who have the wit and the courage to seize it.

Slowing down is a necessity. But it can also be a virtue.

State explicitly that in a world in which everything is accelerating, and events are a blur, and people are increasingly dizzy, you will slow down in order to help readers make sense of the world.

You can even turn into an ad campaign: “We’re slower. That’s why we’re better.”

My hypothesis: A news organization that deliberately slowed down, and advertised that it was slowing down, would suffer in the short term as less scrupulous competitors beat them to Twitter. But, in time, they would slowly come to be seen as a more reliable news organization. A more trustworthy news organization.

And in the long term, the more trustworthy organizations will win.

“What if I’m wrong?”

The great Daniel Dennett has published a new intellectual memoir. In an excerpt, this passage leapt out at me:

What if I’m wrong? Good thinkers frequently ask themselves this question, the way good doctors frequently check their practices against the Hippocratic oath they swore, and not just as a formulaic ritual.

…

What, though, if my supposed insights are just generated by a prodigiously fertile mistake? It’s worth remembering that this has happened before, on a cosmic scale. Descartes wrote his retrospectively preposterous books—Le Monde(eventually published in full in 1667) and Principia Philosophiae (1644)—presenting the first detailed TOE (theory of everything). He had deduced (he claimed) the truth about everything under the sun and beyond the sun, including starlight and planets, tides, volcanoes, magnets, and much, much more, most of it dead wrong. It was Newton’s majestic Principia (1687) that decisively refuted Descartes. Descartes’s theory of everything is, even in hindsight, remarkably coherent and persuasive. It is hard to imagine a different equally coherent and equally false theory! He was wrong, and so of course I may well be wrong, but enough other thinkers I respect have come to see things my way that when I ask myself, “What if we are wrong?” I can keep this skeptical murmur safely simmering on a back burner.

We should all live with an awareness that even our most fundamental beliefs may be wrong. Few of us do. It can be exhausting. And enervating. “What if I’m wrong?” can make us afraid to try.

But as Dennett has shown — as many other thinkers, investors, and leaders have shown — it is possible to hold onto an awareness of fallibility while boldly making claims and pursuing goals. Those who manage this tricky balancing act can benefit from the brash confidence of human nature while reducing the dangers posed by that same brash nature.

Wringing our hands never got us anything. Rushing forward blindly risks everything. Wisdom lies in finding the middle passage.

Cancel culture

I’ve always avoided using the term “cancel culture,” just as I avoid “woke.” When a term becomes a flashpoint in a charged political controversy, it ceases to be mere language. It’s a switch. Say it and whole complex sub-routines are activated in people’s brains. Emotions. Assumptions. Arguments and counter-arguments. After the switch is thrown, what you do or don’t say matters little. The sub-routine does people’s thinking for them.

Only when events confound the programming is there an opportunity to get a word in.

Which is what’s happening right now.

For years, the sub-routine on the left has directed people to roll their eyes when the words “cancel culture” are spoken. There is no cancel culture. It’s an invention of right-wing culture warriors.

But now, in the wake of the Hamas atrocities, we are seeing events like this literal cancellation — a celebration of a Palestinian novelist at the Frankfurt book fair, the world’s largest, was scrubbed — are happening with unnerving frequency. The targets are overwhelmingly on the left of the spectrum. So what should we call this phenomenon? Maybe “cancel culture”?

Can we now have a more mature, more thoughtful conversation?

Some speech has always been, if not illegal, beyond the Pale. Tweet that the Holocaust was splendid — or declare Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassin a hero — and you will be called awful names and socially ostracized. You may also be fired by an embarrassed employer. And that’s fine. Some speech is so appalling that such judgments and reactions may be proportionate to the gravity of the offence.

Proportionality. That’s the key.

When the left dismisses “cancel culture,” the sub-routine’s standard argument is that “like everything else we do in society, speech has consequences. If you appal people with your speech, appalled people will react and your speech will have consequences. Don’t whine when it happens. Just don’t say the appalling thing if you don’t want it to happen.”

But what people object to in “cancel culture” isn’t consequences. It’s disproportionate consequences.

When Alexi McCammond was named the next editor of Teen Vogue, she was fired — or more accurately, had her offer rescinded — when it was revealed she had made racist and homophobic tweets … when she was 16 years old. The consequences were wildly out of proportion to the offence.

What motivated these disproportionate responses? Much of it is simply people eager to display their moral rectitude, like villagers lining up to throw rotten tomatoes at the adulteress in the stocks. But some of it stems from a belief that if we are tougher on racist speech and acts, we can drive racism from society. There was some irony in that position. For decades, “tough on crime” has been a standard tenet on the political right, while it has been rejected and reviled on the left. The core premise of “tough on crime” is that we can punish our way to a better society. Now the left is insisting that we can punish our way to a better society, at least when it comes to racism. (For the record, I don’t think we can punish our way to a better society. Period.)

Debates about how to respond to speech are ultimately not debates about whether speech should or shouldn’t have social consequences. They are debates about proportionality.

Is the blowback proportionate to the gravity of the offence?

That is what’s really at issue, but that is seldom how these debates unfold. Instead, people line up to beat straw men: For the left, it’s “speech should never have consequences;” for the right, it’s “only agreement is permitted.”

Well, now the polarities have been reversed and the sub-routines confused. Maybe we can start thinking again? One can hope.

About that “Techno-Optimist Manifesto”

Regular readers will know I’m not a manifesto kind of guy. No one ever says “on the other hand” in a manifesto.

As Marc Andreesen demonstrated with aplomb when he published his widely discussed “Techno-Optimist Manifesto.”

Andreesen is one of the biggest Silicon Valley venture capitalists. If he says it, you can be sure lots of people in Silicon Valley are saying it. (And lots more people outside Silicon Valley who are paid with Silicon Valley money are saying it.)

Silicon Valley being Silicon Valley, this matters.

There is plenty I agree with in Andreesen’s manifesto. We are vastly better off today thanks to technology. We can do so much more. We must acknowledge that information is highly distributed, and limited, and we have little idea how the future will unfold. We are walking forward in the dark, probing ahead with extended hands, occasionally stumbling, but always learning. Let a thousand experiments bloom.

On the other hand….

Despite the epistemic uncertainty Andreesen acknowledges, and puts at the core of his argument, his overwhelming tone is iron certainty. Regulation is bad! Markets are good! Down with the enemies! Here is a list of heroes! Hail the heroes!

That’s the sort of thing over-caffeinated undergrads write at 3 AM.

I thought about writing a longer, more thoughtful response, but then I read this, by Jason Kuznicki, and I thought maybe I’d just link to it.

We do still need people out there having visions of the future. But also we need humility, and consumer feedback, and serendipity—they’re the space that we leave for everything that we smart folks of today can’t anticipate. The future isn’t coming from any one person’s brain, and we should plan accordingly.

Amen, brother.

Enough with “grifter”!

One of the worst habits to emerge from social media — this is no small claim — is the tendency to sling around the word “grifter.”

Disagree with a prominent supporter of a certain point of view? He’s a grifter. Obviously.

A grifter is a con-man. He doesn’t actually believe what he says. He’s manipulating rubes for money.

Some public figures may indeed be grifters. But evidence is almost never provided when this accusation is levelled. “Grifter” is simply a lazy slur.

That would be bad enough, but grifter does additional damage to discourse.

If someone isn’t sincere in his arguments, you need not engage with those arguments. In fact, it would be foolish to bother. You can just sneer and feel smug for having seen through the con.

That is profoundly anti-intellectual. And — ironically — dishonest.

That's why I was delighted that the linguist and commentator John McWhorter wrote this (narrow) defence of Ibram Kendi.

As anyone following the news knows, Kendi is a leading voice of the “anti-racist” movement that soared to prominence over the past half decade or so. Kendi published two giant bestsellers, commands enormous speaking fees, happily received bucketloads of money from Twitter-founder Jack Dorsey and other rich philanthropists, and created a lavishly funded “Center for Antiracism Research” at Boston University. For the “anti-woke,” Kendi is Public Grifter Number One.

So when Kendi’s Center laid off half its staff, apparently under financial pressure, there was a wave of schadenfreude. The grifter is getting his comeuppance.

McWhorter nails why that talk is wrong.

Deliberate immorality is exceptional. It should be a last resort analysis, not the first one. Accusing Kendi of being a bad man is symptomatic of how eager we tend to be to see bad faith in people who simply think differently from us. To delight in Kendi’s failure as the head of the Center for Antiracist Research is small.

What makes the piece particularly compelling is that McWhorter is one of Kendi’s chief antagonists. He despises — I don’t think that’s too strong a word — Kendi’s work. He has publicly sparred with Kendi countless times.

But McWhorter recognizes that loathing someone’s ideas, gagging on that person’s success, and choking when he rakes in big money, does not in the slightest prove insincerity. Being wrong but successful does not make anyone a grifter.

Got hard evidence that someone is only in it for the money? Show it. Otherwise, please drop “grifter” from your vocabulary.

The uncertainty illusion. Again. And again. And…

Here is Thomas Friedman, the longtime columnist, writing in The New York Times a couple of weeks ago:

A lot of people’s plans — and a lot of countries’ plans — have gone completely haywire lately. We’ve entered a post-post-Cold War era that promises little of the prosperity, predictability and new possibilities of the post-Cold War epoch of the past 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In 2008, I published a book called Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear (aka The Science of Fear in the US). Near the end, I wrote this:

In September, 2003, Friedman wrote, he took his daughter to college with the sense that “I was dropping my daughter off into a world that was so much more dangerous than the world she was born into. I felt like I could still promise my daughter her bedroom back, but I could not promise her the world, not in the carefree way that I had explored it when I was her age.”

Some day, when I have time to kill, I am going to comb through Friedman’s enormous archive looking for all his declarations that the safer, more stable, more predictable world of the past is no more, and now we face a volatile, uncertain world. I would bet my house and my dog — even my dog! — that I can find Friedman bemoaning the disappearance of a safer, stabler, more predictable world at least once a decade for his entire career.

I’m not writing this to mock Thomas Friedman, by the way. Friedman’s mistake is common.

Nor am I dismissing the possibility that the world may really have moved into more uncertain times, in the past or now. Equilibria come, equilibria go.

The issue is hindsight bias and the “uncertainty illusion” it generates. As I wrote in Risk:

Simply put, history is an optical illusion: The past always appears more certain than it was, and that makes the future feel more uncertain — and therefore more frightening — than ever.

Friedman isn’t wrong when he looks ahead and sees uncertainty and volatility. But when he compares that to the past, and declares the way ahead so much worse, he never actually examines that past carefully. He simply glances at the past, which appears more stable, more predictable. And that settles it. We’re in a new “age of uncertainty.”

Remember that daughter who, in 2003, Friedman dropped off into a world that was “so much more dangerous than the world she was born into”?

She was born in 1985. At the time, people were scared out of their minds about nuclear war. And they were right to be scared. The superpowers were eyeing each other nervously and there were several false alarms and close calls. In 1983, when NATO conducted a war-game called “Able Archer,” Soviet Premier Yuri Andropov (a former head of the KGB) was convinced it was cover for a NATO first strike — so he put his forces on high alert and ordered his intelligence agencies to find evidence proving him right. Some scholars now argue that we came closer to nuclear war in 1983 than at any time other than the Cuban missile crisis.

And that’s just nuclear war. Look at what people expected AIDS to do back then. Oprah Winfrey, 1987: “Research studies now project that one in five heterosexuals could be dead from AIDS at the end of the next three years. That’s by 1990. One in five.”

But sure, life was a lark in the 1980s. When you recall it in 2003.

To compare the present with the past, it’s not enough to glance over our shoulder. It takes the determined work of a historian to go back into that past and experience it as the confusing, volatile, uncertain present it was.

Very few public commentators do that work. Like Friedman, they just glance over their shoulders and get scared by the comparison. Then they scare and mislead their readers.

Department of Shameless Bragging

The Financial Times is the world’s leading business newspaper. (I suppose The Wall Street Journal would argue with that, but I’ve got bragging to do so I’m going with it.)

And The Financial Times’ Business Book of the Year (formerly sponsored by Goldman Sachs, then McKinsey, now Schroders) is the world’s top award for business books — an enormous and highly competitive category.

So when How Big Things Get Done was long-listed, I was pleased.

When How Big Things Get Done was short-listed, I fell off my chair.

The winner will be announced December 4, in London, my favourite city in the whole wide world.

I will take long walks, humming Jerusalem all the while.

Read every word. As excellent as ever. Congratulations on your nomination and best wishes. I wish you gave lectures at the NAC in the afternoons. It would be great.

A very perceptive piece. Thank you.

But it should be one of those warnings like “Never play cards with a man called Doc, etc.”

“Never, never bet your dog!”