Don't Trust The Trust Decline

A truism we often forget: What's true in the United States may not be elsewhere.

I’m sure you’ve heard the story about trust. It’s down.

Trust in government. Trust in politicians and corporations and news media. Even trust in each other. All down.

We trust less. We squabble more. Division and polarization are the key features of our time. The theme of this year’s World Economic Forum meeting in Davos was, not coincidentally, “rebuilding trust.”

You’ve heard variations on this theme if you’re American, certainly. But also if you’re Canadian, British, Australian, or some other nationality that shares the English language. You’ve probably heard it in other countries as well, particularly in Europe.

And that matters because trust matters. Trust makes social engagement of all sorts easier, especially economic activity, while its absence weakens bonds and societies. In fact, there’s a remarkable degree of correlation between how much people say they trust other people in their society and economic development. Trust is a very big deal.

“Trust is hugely consequential for us as human beings,” psychologist and sociologist David Halpern said to me recently. “It’s monumentally consequential.”

So today, I’m going to tell you two things you need to know.

First, that story about trust is mostly not true. In fact, in some places, the truth about trust is the opposite. There’s even evidence that the COVID pandemic, far from worsening social fractures, actually gave trust a boost.

Second, a big reason why that false story has spread far and wide is the world’s obsession with the United States (a theme I’ve written about before.) We foreigners sometimes chide Americans for talking as if America is the world. But we foreigners often make the same mistake: The United States is so big and its soft power so great that we can’t take our eyes off it, and we confuse “what is true in the United States” with “what is true in my country” or even “what is true in the world.”

So what is the truth about trust?

It varies enormously. From place to place and subject to subject. Like the world, it’s complicated. And anyone who tries to summarize it all with one simple, neat, compelling story is selling something.

But let’s start where discussions like this always start, the United States.

It will come as a surprise to precisely no one but Americans’ trust in government is not only down, it is at historic lows. Why?

Chances are you can easily come up with an explanation. And chances are that explanation will relate to events of the last decade or less.

I say this because people conjure explanations for observed phenomena as automatically and easily as they breathe. And those explanations tend to be narrowly focussed on the present. That is human nature.

But take a look at the following chart.

Two things jump out. First, the line tends to rise when the economy does well and fall when the economy tanks. And second, the decline in Americans’ trust in government can’t be explained by reference to Biden or Trump or Obama or Bush. It is a phenomenon more than 50 years in the making.

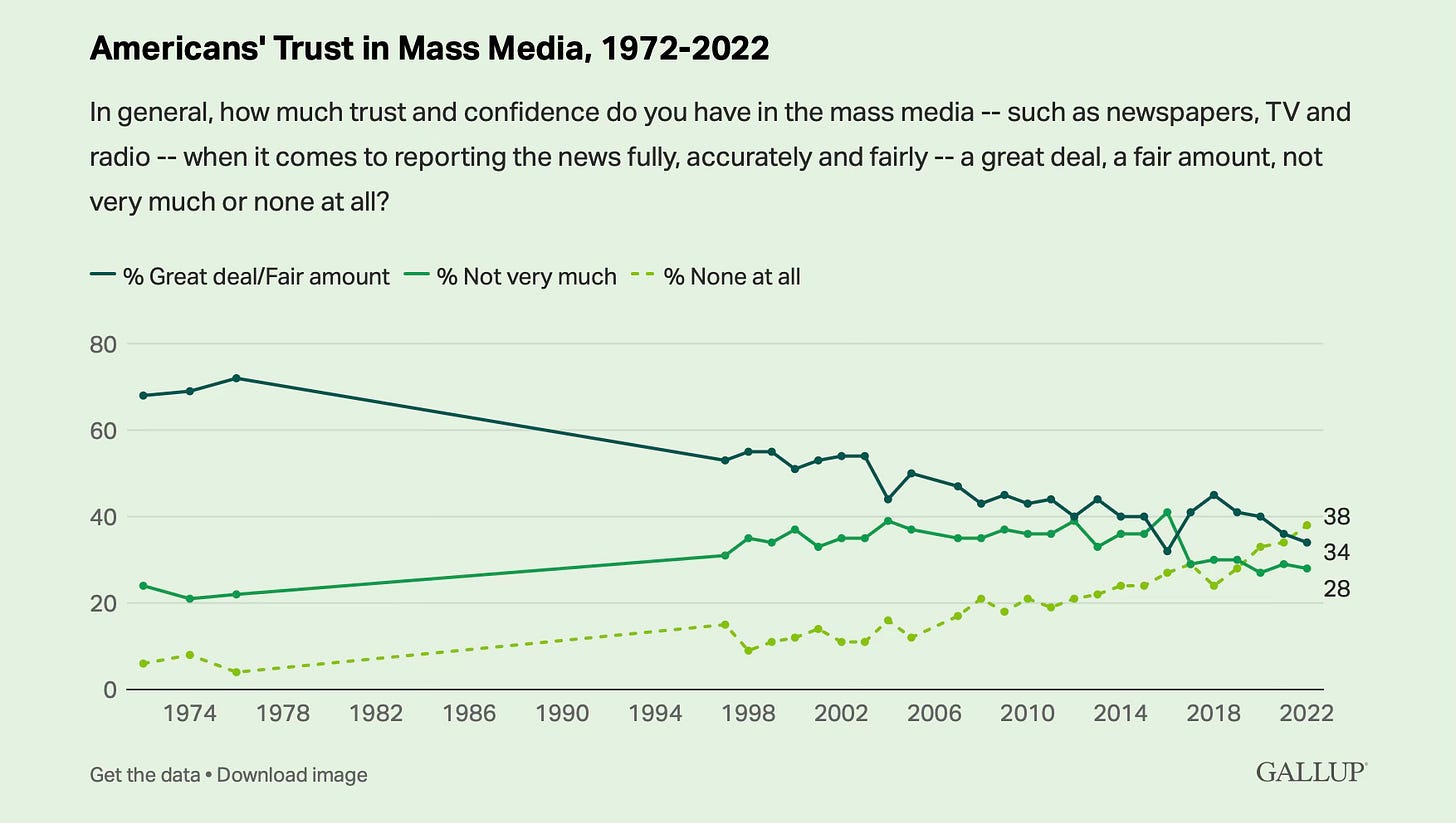

Now consider Americans’ trust in news media.

That is also at record lows. Again, I’m sure it would take you only a second or two to think of an explanation focussed on recent events.

And again, your explanation would be wrong.

Take a look at this:

So that’s another indication that something longer-term and more profound is at work.

There are lots more numbers like that but the most important is how Americans answer the simplest question of all: Do you think “most people can be trusted?”

Why is that number so important? Researchers have been asking that question since the 1950s and it has consistently proved to have remarkable probative power. In fact, scores on that question actually correlate strongly with national wealth. (And yes, causation likely goes in both directions.)

So what do the American data on that question look like?

It’s not pretty.

That’s not down as much as the earlier measures but it’s still a substantial decline. More importantly, it’s a long-term, sustained decline over a half century.

In 2000, the sociologist Robert Putnam published his landmark book Bowling Alone about the long-term decline in American “social capital” — meaning social connectedness and trust. The title comes from bowling leagues. In the 1950s or 1960s, if you bowled, you probably bowled as part of a team or a league. That’s social capital. But by 2000, connectivity in bowling had dramatically declined. People bowled alone.

This long-term decline has been a hot topic in the US since at least the publication of Putnam’s book.

But the United States isn’t merely one of many countries. It is by far the wealthiest country, with the most lucrative media markets, so what Americans say to other Americans is broadcast over the biggest loudspeakers (The New York Times, CNN, Hollywood) in the world. And people all over the planet pay extremely close attention to what Americans say, both for rational reasons — what Americans think makes a difference to the lives of everyone — but also because American cultural pull is immense. The US may not be the “hyperpower” of 25 years ago but its soft power, to use Joseph Nye’s term, is undiminished. In cultural terms, the US is a black hole drawing all things, even light, toward it.

So if the US is suffering a serious, long-term decline in trust, if the US is the most polarized and bitterly divided it has been in modern times, if the US is on a scary trajectory, you get countless foreigners talking about declining trust, and polarization, and the scary direction things are headed. Do that enough and lots of those foreigners will start to blur the distinction between the US and their country. American reality becomes their reality.

If that sounds exaggerated, consider the influence of debates about race in the United States on discourse around the world.

It should go without saying that the long history of black people in the United States is unique. No other developed country has a history that’s even similar. Not surprisingly, the situation of black Americans today, which is the product of that history, is also unique. Education rates, income rates, wealth rates, incarceration rates. Black Americans aren’t just distinct from white Americans. They’re distinct from any group, anywhere. It would be foolish to assume that if something is true for black Americans, it must be true for black Britons, black Canadians, etc.

Obvious, right? And yet, exactly that sort of assumption is often made. Consider life expectancy. Black Americans notoriously have considerably shorter life expectancies than white Americans. So what do you think the reality is in, say, Britain?

I’m very confident that most people assume that black Britons also have shorter life expectancies than white Britons. They don’t. In fact, the average black Briton from the Caribbean lives a little longer than the average white Briton, and the average black Briton from Africa has a much longer life expectancy — longer even than the life expectancy in Japan, which is among the world’s highest. (Similarly, all-cause mortality is lower among black Canadians than white Canadians. I doubt I’ll ever read that in the Toronto Star, although I will read headlines like this.)

The conflation of black realities in the US with black realities in Briton is so common that Tomiwa Owolade, a British author who is black, recently published a book begging people to stop. Its title says it all: “This Is Not America.”

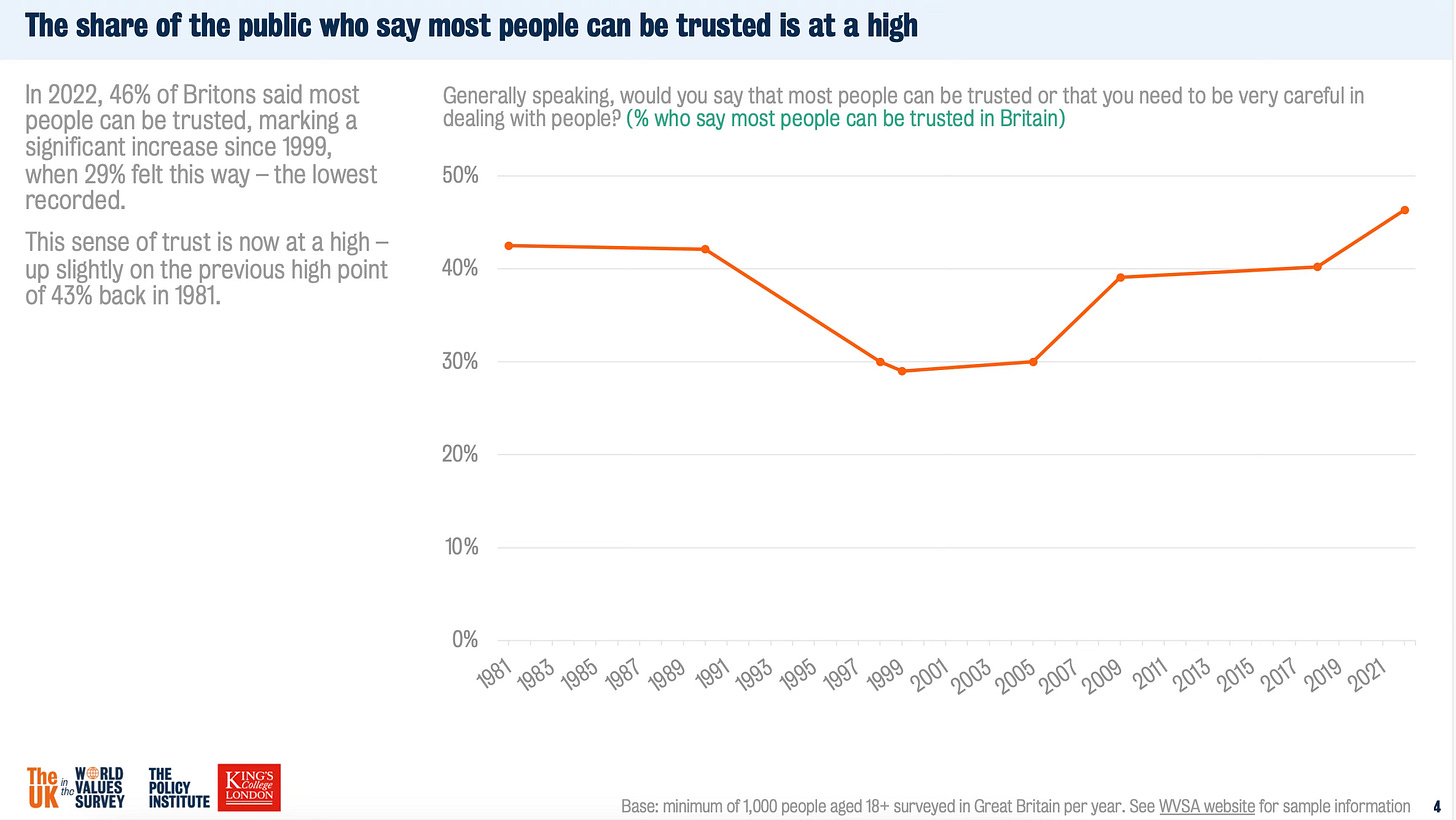

I’m pretty confident a similar phenomenon is at work in trust. Just consider the following headline on a press release issued this past June: “UK Public Among Most Trusting In World.”

A little surprising, yes?

That press release came from the Policy Institute at King’s College London. It’s for a report based on data drawn from the World Values Survey, a major international initiative that has been operating for decades. (The slides I’m using can be found here.)

Gaze in amazement at the all-important general question about trusting others.

Sure looks like good news to me.

And Britain has company in that regard.

And consider this fascinating question: Do you trust people of other nationalities?

That’s a tough one. It’s explicitly saying, “FOREIGNERS!!! Trust ‘em or no?!”

And look at the result.

Now, some of those numbers go back a few years. You may think the COVID pandemic, and all the bitterness and division it spawned, have undone these positive trends.

In fact, says David Halpern, “there's some evidence that COVID in a number of countries looks like it was an accelerating factor for social trust.” That’s because, contrary to the story that emerged from the United States and dominated global discourse — and enflamed by media that focused on conflict while ignoring cooperation — the response to COVID, in so many countries, was overwhelmingly one of people pulling together, following the rules, and making shared sacrifices. People may have hated those sacrifices and thought the policies were a mistake. And they may have been furious at officials like British Prime Minister Boris Johnson who took a “rules for thee but not for me” approach. But for the most part, we cooperated — and we saw others cooperating, too.

That’s good for trust.

As was the image below — Queen Elizabeth bemasked and isolated at the funeral service of her beloved husband, following the same rules as everybody else. (Her Majesty was a leader, unlike the buffoon who was her next-to-last prime minister.)

Incidentally, if you are British and you have never heard of that heartening data about trust that’s likely because the media mostly ignored that report when it was released last June. In part, that’s in line with the negativity bias that skews news reporting not because journalists are horrible people who want to scare the public for fun and profit but because negativity bias is a human bias, and journalists are human. But it’s also because, thanks to the exceptionally fractious response to the pandemic in the United States, and thanks to the overwhelming American dominance in the world’s collective mind, there was a strong, established narrative about how the pandemic worsened divisions and pushed trust further into the basement in the minds of journalists and the public alike. Casting contrary data on that is like casting seed on stone. It’s never going to take root.

My advice?

If you’re not American, burn the title of Owolade’s book into your memory and remember: This is not America.

If you are American, maybe do foreigners a favour and remind them they’re not. And they should count themselves fortunate for that, at least when it comes to trust today.

Seems like a lot of people should ration the mental effort devoted to the USA. Similar to rationing time on social media, a few minutes once a week and not a thought for the rest of your week.

I am going to give this a try.

Your analysis is cheering. However, I quibble about the "trends" on those charts. For example, we see Canada at 43% at one point and 46% ten years later. The sample size (at least 1000) supports confidence limits at maybe plus or minus 3%. Thus, it cannot be dismissed that the actual numbers were 46 and 43 (the other order). Polling is getting tougher and tougher with the demise of cell phones and the increasing diversity on the population. If those average opinions reflect the middle of increasingly polarized views, there is another story, deeper than your summary. Forced binary decisions are also problematic. Can't I trust most people but still be careful? Keep up the good fight.