Eighty years ago today, the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany took effect and the Second World War ended in Europe.

In the United States, May 8th is Memorial Day. At least it was. It may still be. It’s not clear. That’s because, on May 1, Donald Trump announced he was “hereby” renaming Memorial Day, but the “hereby” was a late-night post on social media and, contrary to the president’s apparent belief, not every utterance of the man has the force of law. And the White House hasn’t made it clear if the administration will use formal channels to enact Trump’s latest brilliant idea.

(NOTA BENE: May 8th isn’t Memorial Day. (Can you tell I’m Canadian?) Apologies to my American friends. I must have taken his reference to “renaming” May 8th and unconsciously made the connection. As for the official status of Trump’s plan, this AP story makes a valiant effort to explain.)

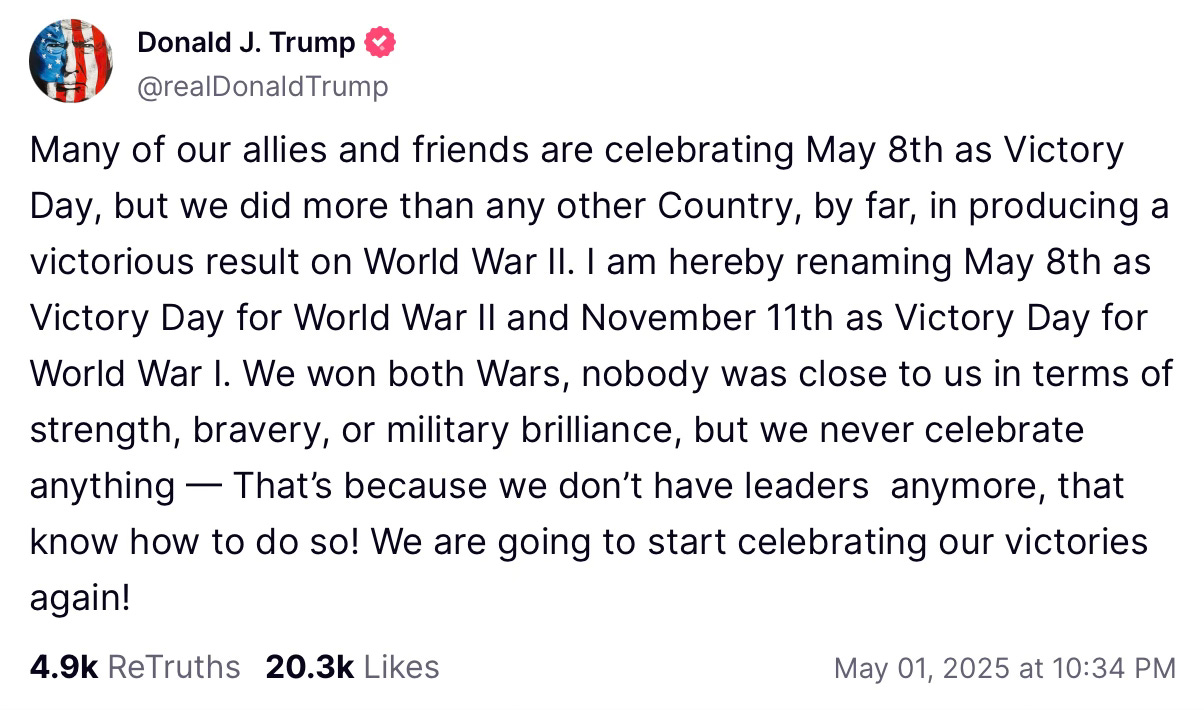

But whether the plan goes ahead or not, it’s worth reading exactly what Trump wrote.

Note the “again.” Trump seems to believe that somewhere in the American past, there were leaders who talked like he does. There were not. Ever. His is the language of Vince McMahon, not Franklin Roosevelt.

In fact, what Trump wrote is antithetical to the spirit that actually won the war and built the post-war global order. On the eightieth anniversary of the hinge-point of the 20th century, I want to briefly reflect on that spirit to underscore what America is losing in the Trump era.

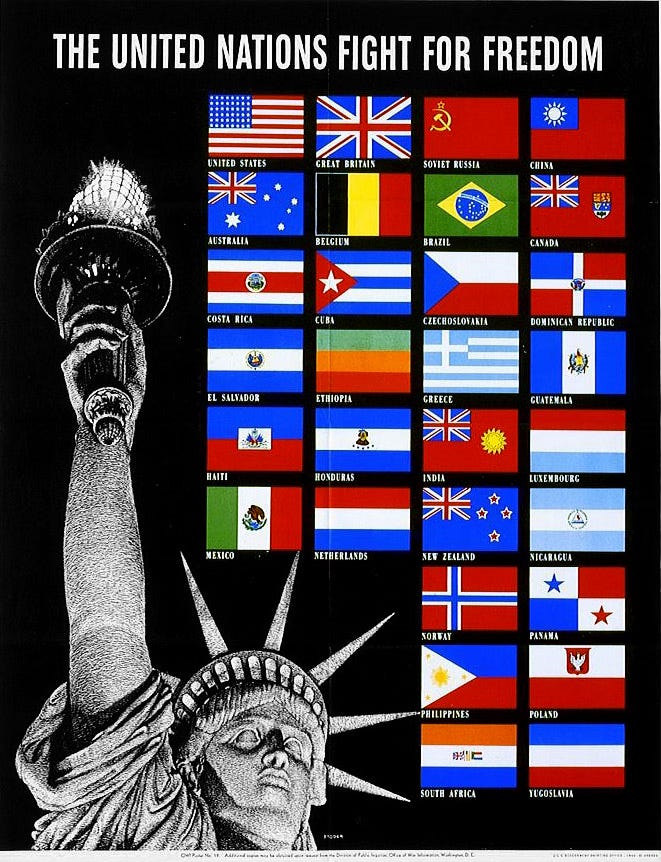

The Allies typically did not call themselves that during the war. They called themselves the “United Nations.”

That started, formally, on January 1, 1942, in Washington DC, when representatives of the United States, Great Britain, China, and the Soviet Union signed a declaration of alliance. It was mere weeks after the Japanese Imperial Navy had wiped out much of the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor; Nazi dominion extended from France to the outskirts of Moscow. The world stood at the brink of a dark age, and the nations of the world rallied. On January 2, 1942, representatives of 22 other countries signed on. By the war’s end, the declaration had 47 signatories.

The global nature of this crusade was reflected on the battlefield. Steven Spielberg taught the world that the invasion of Normandy was an American triumph, but only two of the five beaches seized on that day were taken by Americans, while the other three fell to Britain and Canada. And the coalition present on that day was much broader than that. Among the Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen at Normandy, there were French, Australians, Czechs, Poles, Dutch, Norwegians, New Zealanders, Greeks, and South Africans.

Look carefully at many famous battles of the war and you’ll see the same startling diversity. Indians and Brazilians fought in Italy. Czechs flew Spitfires in the Battle of Britain.

The Allies called themselves the United Nations because they understood their cause to be international and global. The world would struggle together, or the world would perish.

In 1943, University of Michigan historian Preston Slosson published a slim book entitled After the War — What? It makes for fascinating reading today because Slosson framed what he expected would be America’s great debate of the post-war years.

I want to share what he wrote, verbatim, taking from a chapter entitled “America’s Place in the World.”

America’s Place in the World

Two main problems confront the American people as they look forward to the days beyond the war. One of these questions is the relation of the United States to the other nations of the world. Shall we strive to be sufficient unto ourselves, or seek cooperation with others? The other question is how we can sustain and improve the high level of prosperity which our nation has generally enjoyed, throughout the difficult years of postwar reconstruction. These two questions are not independent of each other. On the contrary, our domestic policy and our foreign policy are so intertwined that one cannot discuss either without having the other in mind.

1. AMERICA AT THE CROSSROADS

In general, there are two ways of looking at our position in the world.

One group argues thus: Our American problems will require all our attention, all our effort, all our wealth. If we try to solve the problems of other countries at the same time, we may fail in both. For military security let us maintain such an army, navy, and air force that no one will dare assail us; if that does not suffice, let us make military alliances as we need them, but always remain free to withdraw from them when we wish. Let foreign trade be merely a convenience, not a necessity; and, to that end, let us protect our domestic market by tariffs, while we develop by subsidies the industries we now lack. Rubber can be grown on the Amazon as well as in Malaya; for that matter we are now making a good deal of it in factories right here in the United States. We never again want to be caught dependent on anything we cannot raise or make for ourselves. As for immigration, let us suspend it for a few years until all aliens now amongst us have been thoroughly assimilated to American ways, so that we may not become a “polyglot boarding house” instead of a united nation.

The other group replies: The dream of isolated independence ended when the airplane was invented. You can ring your country round with a “hoop of steel” but you cannot roof it over. If wars are permitted to occur at all, we shall be dragged in somehow, as in 1812, 1917, and 1941. Security for America necessitates security for all the world. Nor can we hope to be prosperous all by ourselves. Doubtless we could learn to do without the goods we cannot make or raise, but what a pinched, narrow, and wasteful way of doing things that would be! Is it wiser for North Dakota to raise bananas in greenhouses at great expense, or buy them cheaply from Costa Rica? Moreover, if we do not buy abroad we cannot sell abroad, and that reduces our market and lowers our standard of living. All the world must enjoy “freedom from want” so that we may enjoy it too.

In some such terms the national destiny will be debated for many years to come, and the decision will be yours to make. Upon that decision will depend not only the future of the United States but, to a great extent, the future of every land.

What Slosson laid out was the then-familiar debate between America’s isolationists and internationalists, whose origins lay at the conclusion of the First World War. But he was wrong about this being America’s great debate “for many years to come.”

The international character of the fight against fascism was so strong, and the folly of isolationism had been made so clear by the outbreak of another World War, that when the Allies won, and the work of crafting a post-war order began, leading Americans were overwhelmingly on the side of internationalism. Isolationism didn’t disappear entirely. But it was a shadow of the force it was before the war. The spirit of the “United Nations” dominated America.

Despite emerging from the war as a colossus with unparalleled economic might, American statesmen of that era would never have dreamed of speaking with Trump’s bombast. Not about who contributed what to the victory. Nor about anything else. They had no use for hubris and displays of power. Instead, they wanted a genuinely international, cooperative, open world in which trade crossed borders, not armies. So they created the Marshall Plan, the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, and the other architecture of the post-war order.

And it worked. For all the failings of the post-war order, it delivered an unprecedented era of (relative) peace and prosperity.

The post-war order was good for the world. It was even better for America. Presidents came and went, handing power from one party to the other, but they all embraced the wisdom of the internationalist view.

Until Donald Trump.

Today, it’s hard not to see at least some of the MAGA worldview in Sosson’s description of the isolationism. But there’s also much of MAGA that isn’t there. The relentless arrogance. The braying and bullying. The isolationists of Calvin Coolidge’s era wanted America to mind its own business, avoid entangling alliances, and spend as little as possible on the military; the isolationists of the Trump era have no use for alliances either, but they see America’s business as building up its military and shaking down other countries. Or as Trump calls it, “making deals.”

With the guarantor of the post-war global order rapidly turning into an enemy of that order — as is any nation that threatens to change borders by force — what was built starting 80 years ago today is crumbling rapidly. The lessons we learned from the staggering tragedies of the first half of the 20th century are fading like a morning fog. The spirit of collective struggle that allowed the world to survive the darkest days and forge one of the most peaceful and prosperous eras in history has been replaced by the hubris and greed that almost destroyed humanity.

It’s wrong to say people don’t learn from history. But sooner or later, it seems, we forget.

A very good analysis. I would suggest that readers look at the Canadian contribution to WW1 and WW2. The miners tunnelling under Vimy Ridge in WW1, leading to a rapid victory rather than the blood bath that occurred prior. The reason that the Netherlands to this day sends 20,000 tulip bulbs to Canada to be planted in Ottawa (They sent 1.1 million bulbs in 2024 for viewing this year) . The reason that Dutch children light candles at the graves of fallen Canadian soldiers buried there. I could go on. Others were in the fight long before the Americans came in.

Had been hoping to have your thoughts on this very important day in history, Dan. Thank you. Am sharing as widely as I can