Fools, Tools, and Liars

You are rational and objective. Why can't everyone be reasonable like you?

In this post, I will answer a question you probably ask yourself when you go on social media websites: “Why are so many people such complete jackasses?”

They’re ignorant. They’re stupid. Their thinking is blatantly skewed by psychological biases, but they can’t see it. Or worse, their thinking is driven by malign motives, which they deny no matter how obvious. And they absolutely refuse to see reason and change their minds.

They’re fools, tools, and liars. You wish they couldn’t vote. And you can’t understand why more people aren’t rational and objective. Like you.

Hence the question: “Why are so many people such complete jackasses?”

The foundation of the answer lies in some elementary neuroscience and epistemology.

To understand it, I want you to stop reading and look up. What do you see? A kitchen table, maybe. A chair. A tree in your backyard. Your dog. Someone in the subway seat opposite you.

Whatever it is, you know that what you are seeing is the objective reality around you.

Simple, right?

Except it’s not objective reality. Perceiving it as such is an illusion.

The belief that we experience reality directly is called “naive realism.” Psychology and neuroscience picked up the term from philosophy. It means the belief that we experience reality directly, unfiltered, unmediated. And it is wrong.

You do not see that table, chair, or whatever directly. You see an image of the table, chair, or what. That image is painted by your brain.

The brain is a good painter. Much of the image you are seeing does correspond with objective reality. The brain manages that, in part, by using information that flows from that reality. If your chair is blue, for example, your eyes detected light waves bouncing off the chair. Your brain worked that information into its painting.

But do you remember that long-ago primary-school lesson about how light and colour work? The chair looks blue to you because the frequencies of light that correspond to other colours were absorbed by the chair, while the blue light frequency bounced off the chair and entered your eyes. So is the chair objectively blue? I suppose you could argue it is “objectively” every colour but blue. Or maybe not. Funny how even something so simple can be complicated.

Also remember that the visible light which the human eye can detect is only a small portion of the electro-magnetic spectrum. There are all sorts of other frequencies we are blind to. If you could see those frequencies when you look at your blue chair, you would think you were having an LSD flashback. And yet, seeing the whole of the electro-magnetic spectrum would be much closer to seeing the full, objective reality.

There are lots more illustrations like that. Every human eyeball has a blind spot, for example, where the optical nerve attaches to the retina. But we never see the blind spot — because the brain automatically takes whatever it sees around the blind spot and fills in the blind spot with that.

What’s fascinating about naive realism is that it’s essentially impossible to shake. I know that I don’t see reality, only my brain’s painting of that reality, but I can’t stop seeing it as if it were reality. That’s what makes optical illusions so fascinating. We see “objective” reality. But when we see the illiusion, it violates what we see. Which feels impossible. Yet even after the illusion is explained, we can’t turn it off. We keep seeing the impossible.

And when two people look at the same thing and see something different? It is mind-blowing.

If I look the dress below and see it is white and gold (as I do) I am seeing objective reality. If you look at the same dress and say that it is blue and black, I am stunned.

Did you really look?! Look again.

If you say you still see a blue and black dress, I am unsettled. Is there something wrong with your eyes? Maybe you should get your eyes checked.

The famous 2015 blowup over “the Dress” was built on naive realism.

There’s a good reason for the stubbornness of naive realism: Particularly in the past, survival required quick, automatic responses. Detect motion on the ground at your feet? Jump back! See a large beast emerge from the long grass? Run! If we experienced our perceptions of reality not as objective truth but as the subjective interpretation of reality they are, it could undermine that rapid response: “Was the motion I detected at my feet real or was it a momentary misperception in my brain’s painting of reality?” The snake just bit you.

So naive realism is a powerful illusion because it is a valuable illusion. It kept our ancestors alive. And it does the same for us, in certain situations, like when you are about to pull into an intersection and spot a car blowing through a red light.

But the consequences of naive realism go well beyond mere visual perception and reflexive reactions.

From a piece I wrote a couple of years ago:

I have presented all this in terms of vision. But the brain does a lot more than paint static images. It also makes sense of what it’s seeing. And it anticipates what will happen next.

It does this using prior experience and existing beliefs.

If I see a flash of red in the branches of my maple tree, I’ll immediately conclude it’s the male cardinal, the only bird (in this region) that is all red. I will also feel that it is here, as so often in the past, to get the seed in the bird feeder that hangs off a branch of the tree. And I will expect to soon see the female cardinal, because I know cardinals spend their lives in pairs and seldom appear alone. All these perceptions and expectations are the product of what was described above as a “mental model” — my brain’s construct of what cardinals are and how they behave.

Now imagine taking someone from a country where there are no cardinals, putting her in my chair, and having her lsee exactly the same flash of red that I saw. What will she make of it?

I don’t know, of course. But I can be certain that even though the sensory input she gets is exactly the same as the sensory input I got, her sense of what she sees will be different. Because she and I have different experiences and different beliefs. Because she and I are using different mental models.

It is not only possible for two people — reasonable, honest people — to look at the same situation and draw very different conclusions. It is normal. It is routine. Given what we know of how humans perceive, think, and decide, it is exactly what we should expect.

Reasonable people not only can disagree. They should disagree, at least to some extent. It is the absence of disagreement that we should find alarming. “If everybody is thinking alike,” General George S. Patton once wrote, “then somebody isn’t thinking.”

That, at least, is what we should think if we are familiar with naive realism and mindful of how the brain makes sense of the world. But most people are not aware of any of that. And even those who are, struggle to apply it in daily life. Because naive realism is tenacious. It does not turn off. It does not want to be denied.

So we get some very familiar human behaviour.

You look at a situation.

You learn some facts.

You make sense of the situation. You connect the facts. You draw a conclusion. You now have a belief.

I look at the same situation. And I tell you I have a belief, too. It is the opposite of yours.

How do you feel about that? There’s a good chance you find that as unsettling as you did when you looked at The Dress and clearly saw one thing but others looked at it and saw something else.

“How can you possibly believe that?!”

Your reaction will be the same, too. Because it’s following a simple sort of logic.

You looked at objective reality and saw one thing, and I am telling you I saw something else. It follows — “logically” — that I did not look at the same thing as you and, as a result, I am missing information you have. I am, in a word, ignorant.

But there’s a cure for that! Give me the information I lack. Then I will see things the way you see them.

So you ask me to look again. And you helpfully provide me with facts and figures.

I do as you ask. And I say I still see things differently than you.

You are floored. My ignorance has been cured yet I still don’t see things as you do! How is that possible?! (In the corporate world, this little drama plays out all the time, and at considerable expense: When corporations have external problems — consumers or regulators don’t see something the way the corporation sees it — they commonly create a communications strategy to fix the problem. “They don’t see things the way we see them? They must lack information! Let’s give them that information, then they’ll see things the way we see them.” These strategies commonly fail because they misunderstand both people and the problem.)

If ignorance can’t explain my strange belief, what can? There’s an obvious possibility.

I am stupid. A little thick. Not the sharpest axe in the woodshed.

Nothing cures stupidity, but with patience you can help the dim-witted get to the right conclusion. You just have to urge them to think more carefully. Give them a little nudge here and there. Guide them along.

So you do that for me.

And after much patient coaching, I declare that I still hold a view contrary to yours.

Now you are flummoxed. What is wrong with me!? You need an explanation!

A final possibility dawns on you.

I am not ignorant.

I am not stupid.

I must be … lying.

I am not arguing in good faith. My words are not sincere. Why would I lie? Well, that’s obvious, isn’t it? I have a secret motive that compels me to hold my clearly incorrect view.

Now you start to lose your patience with me. And if this little drama continues much longer, it is just a matter of time before you start to feel real animosity toward me. “You know what you’re doing,” you hiss.

Now, remember, that this whole time, it is likely that I have also been thinking along the lines created by naive realism. I think you are ignorant. Then I think you are stupid. Then I doubt your sincerity.

And you are getting hostile with me? And making insinuations about me?!

How DARE you?!

You know where this is going, right? You’ve seen it on social media a thousand times.

A simple disagreement ends with strangers screaming profanity at each other.

I insult your parentage. You declare my genitalia inadequate.

And we both walk away grumbling, “why are so many people such complete jackasses?”

Do I exaggerate?

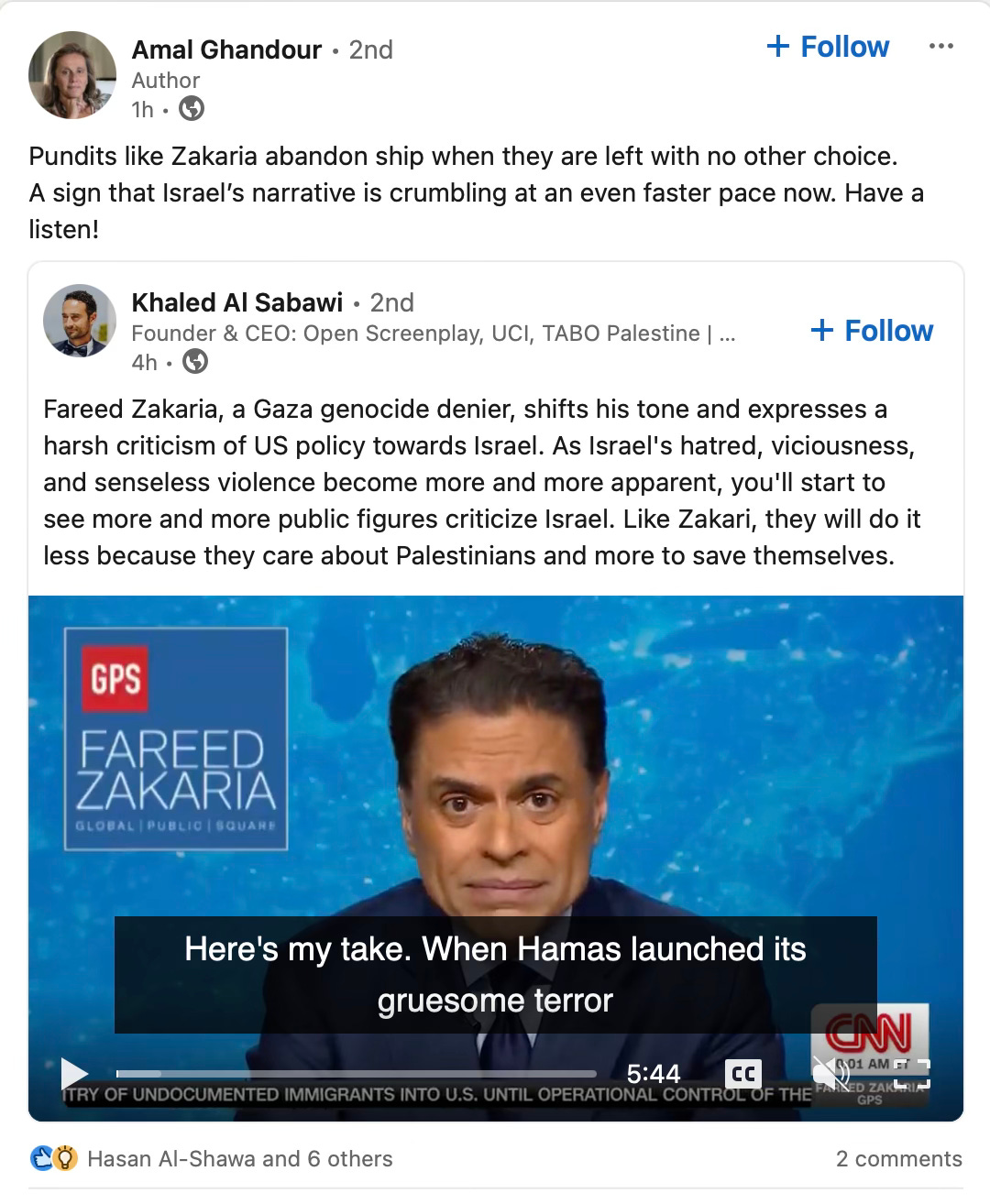

Following is an exchange I saw on LinkedIn. It touches on the war in Gaza but I’m not interested in that. Nor do I post it because it is extreme. Just the opposite. I post it here because it is a typical specimen of something that happens routinely, every day, on social media.

Fareed Zakaria is a famous pundit on CNN. He writes and comments mostly on global politics. As noted above, he supported Israel in the weeks and months following the October 7 atrocity. And he supported the US policy of backing Israel. As Zakaria noted in his commentary, the American policy was to back Israel but use its support to urge Israel to show restraint in attacking Hamas by taking as much care as possible to minimize the death and destruction for innocent Palestinian civilians. But Zakaria now says that policy has failed because Bibi Netanyahu chose to ignore Biden’s warnings. The devastation in Gaza is massive and rising. For both humanitarian and strategic reasons, Zakaria concluded, a major revision of US policy is in order.

Again, note, I am not discussing Gaza. I am only summarizing Zakaria’s stated views. Zakaria says he has changed his mind because he feels the facts on the ground have changed.

So what do the two people commenting on Zakaria’s commentary make of Zakaria’s contrary views?

They don’t accuse him of ignorance. This is Fareed Zakaria. That would be ridiculous.

They don’t accuse him of stupidity for the same reason. This guy is one of the most prominent global affairs pundits in the world.

So what could possibly explain why Fareed Zakaria’s views are so contrary to what is clearly, obviously, objectively true? It must be bad faith.

Zakaria is simply lying. His views aren’t sincere. They are the product of craven, self-interested calculation. The second commenter even turns this supposed observation into a general rule: Pundits “abandon ship when they have no other choice.”

I don’t know either of the two commenters above but I am near-certain that neither has telepathic powers. So how did they determine Zakaria is insincere? How do they know his secret motivation?

Because they see the objective reality. Zakaria’s views contradict theirs, but he’s not ignorant or stupid, so there is only one remaining explanation for his bizarre insistence on believing what he believes. And as Sherlock Holmes said, “when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Clearly, Zakaria is a lying, snivelling worm. The logic is irrefutable.

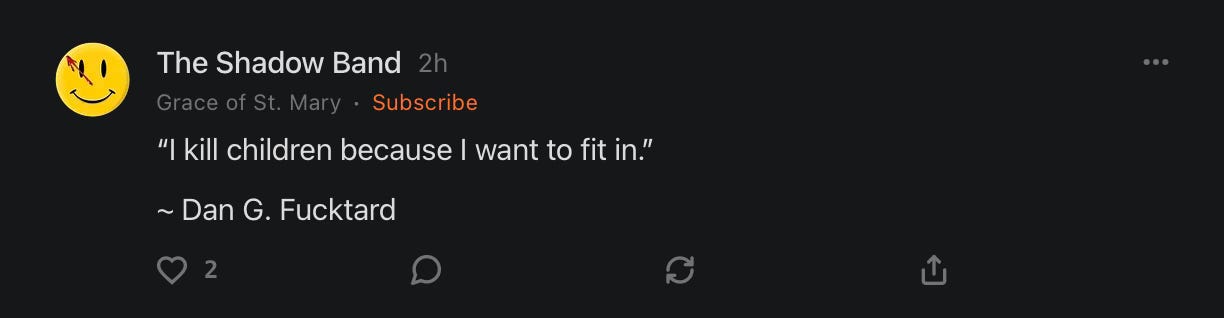

Here is another, blunter example.

A while ago on Notes (that’s Substack’s Twitter equivalent, and if you’re not following me on Notes, what fun you’re missing) I posted a short commentary about the war in Ukraine. I support Ukraine. I support sending weapons and ammunition to Ukraine. When countries suffer unprovoked invasion by the armies of murderous dictators bent on imperial expansion, and innocent people are subjected to rape, torture, and slaughter, I tend to be sympathetic. I am funny like that, I suppose. But agree or not, that is my view. And my motive. (Full disclosure: I am neither an official of the government of Ukraine nor the CEO of Lockheed Martin.)

Some people objected to my views. That’s more than OK. Civil debate is good for everyone.

But there was little civility in the objections. Most started at “warmonger” and proceeded to drop f-bombs, call me an ignoramus and say I am a victim of Ukrainian propaganda. Insults flew. And what would a social media debate be without attacks on my obviously malign motives? I asked several of these people to try again, this time going easy on the f-bombs and whatnot and focus instead on arguments and evidence. I promised I would read and think about reasoned disagreement. But that only made them angrier and nastier.

This snippet sums up the experience.

Again, I am not posting this because it’s exceptional. Just the opposite. While this may be an unusually vitriolic specimen, the reasoning — as it were — is routine in popular discourse.

On contentious issues, it is not possible to be a reasonable person who, unfortunately, is wrong. If you disagree, there’s something wrong with you. Maybe you’re ignorant. Maybe you’re stupid. Maybe you have secret, twisted motives, like wanting to kill children to fit in. (I don’t understand, either. Never mind.)

Whatever your problem is, you clearly have one.

This is why disagreements far too seldom end with both parties shrugging and saying amicably, “reasonable people can disagree.”

Reasonable people can’t disagree! If you disagree with me, you are, ipso facto, not reasonable!

Disagreement is unreasonable: That’s the unspoken assumption in so much popular discourse. Thanks in large part to naive realism.

And every time we apply it, humanity gets a little dumber.

Of course, if naive realism were the root of all nasty disagreement, life would be easy. Publicize the hell out of it, make people aware of the trap, raise collective consciousness, and presto! Humanity gets smarter and happier.

But sometimes, people really are ignorant. Or stupid. And sometimes they really do speak in bad faith. And it’s important that we be on guard for each of these possibilities.

The challenge is distinguishing between real ignorance, stupidity, and bad faith from the appearance of each of these caused by our own naive realism. There’s no easy answer for sifting one from the other.

But the indispensable first step is recognizing the trap set by naive realism.

After that, the standard tools of skepticism apply. Always ask yourself “why do I think this is true? What evidence is informing my judgment?” And the big one: “If I traded places with the person I’m arguing with, would I still find the argument and evidence I am using to be as compelling as I think now?”

But most of all, avoiding this trap involves reminding ourselves, constantly, that reasonable people can disagree. In fact, reasonable people will disagree. It’s one of life’s few certainties, a reflection of both reality and human cognition. We shouldn’t regret that, or deny it. We should accept it. Even embrace it.

And please don’t forget it’s perfectly fine to end an argument with a shrug and a smile.

Good article. Good quote from Patton - it is very distressing to see unanimity across large bodies of politicians on certain issues. Agree that the hostility expressed on Twitter and now Substack isn't pleasant, anonymity partly breeds this. And there really are bad faith actors out there.

Great post, Dan!

https://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/culture_conflict#:~:text=Culture%20is%20an%20essential%20part,ideas%20of%20self%20and%20other.

Culture is an essential part of conflict and conflict resolution. Cultures are like underground rivers that run through our lives and relationships, giving us messages that shape our perceptions, attributions, judgments, and ideas of self and other.