Free for a limited time only!

Some home news. Plus a list of good reads. Even a TV recommendation.

I’m taking a family road trip soon, so, for a few weeks, I’ll be unplugged from the great, throbbing brain that is the Internet. Barring misadventure, we’ll drive through Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, on our way to New Brunswick. The driver’s goal is to find portraits of dead presidents in antique stores. Last time we did this trip I landed a first-term Franklin Roosevelt, and now I dream of finding a dusty Coolidge or a mouse-chewed Wilson. Or maybe a portrait of Hoover where his expression moans, “why did I want to be president?!”

Incidentally, a little-known fact about Maine is that there are more antique stores than moose, lobsters, and residents combined. The family driver finds this delightful. Others in the car see it as a strong argument for skipping the state.

This leads me to the following important housekeeping note:

When I started PastPresentFuture in the spring, my goal was to produce at least one reasonably substantial piece a week. With experience, I still think that’s feasible. But in the last month, work and family intruded and I fell well below that bar. Now I have a family vacation coming, followed by other pressing matters, and August isn’t looking good by this metric. This isn’t fair to paid subscribers. So I’m going to click on a very handy Substack feature which allows payments to be stopped, meaning no new payments are charged, and existing payments are extended as long as the pause remains in place. I’ll keep that pause on for at least a month, although I expect to be writing at least occasionally sooner than that. I’ll only switch it off when I manage to get back to a normal writing pace.

While I’m on the subject of filthy lucre: Thank you. Sincerely. Enough of you have signed up for a paid subscription that this newsletter, in effect, has paid for me to do some expensive research, and more to follow. (It’s mostly expensive because I’ve been ordering old books and copies from archives. I love archives, and archivists, but great Caesar’s ghost it’s expensive to get documents whose value to your research you can’t possibly know until you hand over your credit card.) I haven’t written about that research but I will, sooner or later, because — forgive my enthusiasm — it’s fascinating. I really can’t wait to share it.

But now, before I go, here’s a random collection of things I’ve read or seen that I thought may be of interest:

First up is the Substack publication SHuSH, by Ken Whyte. As Canadian readers will know, Whyte is a long-time journalist, editor, publisher, and author (his biography of the aforementioned Herbert Hoover is superb). He launched his own small publishing business, Sutherland House, and his newsletter is routinely filled with practical insight into the world of publishing. In particular, check out his reporting on the trial in which the US Department of Justice is trying to stop Penguin Random House from buying Simon & Schuster.

It’s insightful stuff for a number of reasons, but two stand out for me: First, the evidence of how bad publishers are at forecasting sales is remarkable, but even more remarkable is the evidence that publishers don’t seem to think this is important enough to take even the elementary steps — like precisely scoring the accuracy of forecasting, reviewing results, and adjusting in light of what experience teaches — needed to correct it. They are far from alone in this, it bears repeating. Whole industries spend vast amounts of money on the forecasting that informs key decisions yet it is quite common for those industries to do very little to ensure it is as good as it could be. This seems self-evidently ridiculous, but that’s our species, ladies and gentlemen. (For those who still think that maybe, possibly, we actually could do a little better, may I recommend a book?)

The second reason it’s interesting to me? I write books for a living and the numbers Ken presents in that piece pretty strikingly illustrate (warning: self-pity ahead) how precarious the financial position of authors has become. And that’s despite the fact that the focus of Ken’s piece, and the trial, is on high-end author advances of $250,000 or greater. Fewer than one percent of all advances — yes, one percent — are in that ballpark. And the gross numbers involved are impressively large. One could reasonably imagine that the lucky author who lands a contract like that now sleeps on Easy Street. But I can assure you the lucky author does not because that gross figure is highly misleading. First, you must take fifteen percent off the top to pay your agent. (Without whom you would starve, so begrudge not.) Then you have to divide the advance into four separate payments, one made when you sign the contract, another when you deliver the manuscript, a third when your book is first published, and the last made when the paperback comes out. For a non-fiction writer like me, that time span can easily be three, four, five years, or more. On top of all that, expenses incurred in the writing of the book — like buying old books or paying archives for copies — have to come out of the advance. As a result, you can easily land what the vast majority of authors would consider a magnificent contract and yet only net $50,000 a year. Or less. With zero job benefits. No pension. And not an ounce of security after the contract is completed. Thus, even if you are the rare author who lands one of these contracts, you are decidedly not a fat cat and you better bloody hope your book sells and sells and sells.

That said, the thrill and glamour of saying “I am a New York Times bestselling author” will keep me warm, I am assured, should I find myself sleeping under a bridge.

Before I wrote books, I was a newspaper journalist with a focus on public policy, and before that I was a policy advisor in a couple of political offices. And always, I have been an avid student of history. To me, the idea that history has an important role to play in the development of effective public policy is rather like saying, “humans need water.” And yet, the value of history to public policy needs to be stated, loudly, emphatically, and repeatedly, because it is far from obvious to a startling number of policy makers.

So I was delighted to be directed to this series of blogposts about history and policy. “Any institution that has no sense of where it has come from is adrift,” writes Sir Anthony Seldon, historian and former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Buckingham.

If you’re on Twitter, follow @fakehistoryhunt. If you’re not on Twitter, check out the website. A Dutch historian, she does the holy work of investigating supposedly historical images and clips making the rounds of social media. I first came across her work when a photo of a European wearing a pith helmet, no less, went viral on social media — because the European in question was in a basket on the back of an Asian woman. This photo was presented as an illustration of what scum European colonizers were. Imagine a perfectly healthy man using a small woman like a pack mule! Outrage! Fury! Now, stop for a moment and think about this and it’s obvious that something’s off: Why on earth would even the vilest man want to be stuffed into a basket and bumped and jostled along by a vehicle that gasps and wheezes as it goes? But the narrative presented supported a firmly held political view, and, as psychology teaches, skepticism goes out the window when that happens. Enter @fakehistoryhunt. What I love about her account of checking this nonsense is how careful she is, and forthright in acknowledging an initial mistake of the sort that would take most people in, and how tentative her conclusions arenbecause that is all the evidence permits, as is so often the case. Good stuff.

And speaking of real history, there’s lots on Substack. Here are a few you might want to check out: Annette Laing is a former academic who keeps the writing decidedly non-academic at Non-Boring History. As someone who loves distant, tiny, empty museums, I particularly like that she travels about visiting such places and writing about it. The economist and economic historian Brad De Long is also on Substack, and he has a Whompin’ Big History Book coming next month which he’d love to tell you about. Kevin Levin writes about the US Civil War and its place in popular memory. Here’s his take on whether the US is headed toward Civil War Part Deux.

The history of abortion and its regulation in the United States is, unfortunately, highly relevant today. I found this 2016 review of the history fascinating. It’s also a good reminder that, contrary to what conservative jurists seem to want and expect, history is routinely far more complicated and contested than we imagine.

We’ve all seen the Internet memes featuring the photo of some famous person in the past, his face haggard and grave, eyes weary … and we are told that when the photo was taken, he was 22. This has spawned the popular perception that “people looked older in the past. This fits if you imagine the past as a time when all were malnourished, children worked in coal mines, anyone who reached 50 must have looked like Ebenezer Scrooge. If, however, you picture the past as a “slower, simpler time” bathed in golden light, it is a little more puzzling. In either event, this is a thorough consideration of whether, in fact, people did look older in the past, and if so, what could account for it. I’ll just share these two photos of James Thurber, American author and New Yorker writer. Can you guess how old he was when each was taken? Answers in captions.

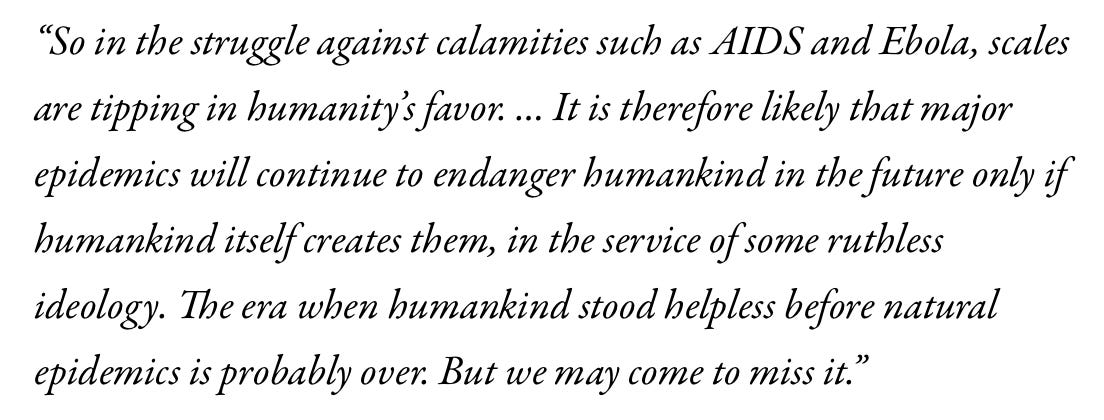

Historian Yuval Harari has developed a lucrative career as a universal prophet, with books that purport to look far into the future and audiences lapping up his every word like he’s the lovechild of the Dalai Lama and the Oracle of Delphi. As the reader may sense, I am not a fan. It’s not that I think he’s particularly bad at forecasting, mind you. It’s that I think long-view, grand-scale prediction of the sort that has Harari’s audiences enraptured is quite beyond the powers of mere mortals. In a century or two, I am confident, his readers will chuckle as often as I do when I read similar oracular pronouncements published in the 1920s and 1930s. Except few will. The fate of all such books, even the most spectacularly successful and popular, is to be entirely forgotten long, long before the future they predict comes to pass. Royalties and speaking fees are paid in the present, however, so I weep not for Mr. Harari.

However, in all such books, there are occasional comments which, as Fate would have it, can be judged sooner than expected. Here is one in Harari’s Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, published in 2017, a mere five years ago.

To be fair, Harari only wrote that we may come to miss it….

The best thing I’ve seen on television this year is “Severance” on Apple TV. Yes, it sometimes has the pace of a sedated bureaucratic. Often, the nothing happening is the point, which can be a challenge in our over-stimulated times. But it’s worth getting into its strange and unsettling headspace because, when you do, it becomes fascinating and funny. Remember The Prisoner, the 1960s pinnacle of psychedelic televisual weirdness? It’s like that. But stranger. Plus, it has John Turturro and Christopher Walken turning up the weird to eleven. Not even a holographic Patrick McGoohan could top that.

But what really hooked me was the core premise. A major corporation — which feels sinister and creepy although we don’t know what it makes and sells — has developed a procedure called “severance,” in which a person’s memory is divided: When people go to work, they remember only what happened at work and know nothing about life outside work; when they leave the office, they remember nothing of work. We follow a small group of people who choose to undergo the procedure for various reasons. They go to work, sit in slightly surreal cubicles, and do routine, boring, seemingly pointless tasks. They go home. They return to work. Repeat. But with time, segregated memories accumulate and the “innies” and “outies” — the term employees use to refer to their selves at work and at home — grow apart and even behave at cross-purposes to each other. Which makes perfect sense. After all, what makes you you? Memory. It’s the core of identity. Without memory, you’re no one. And if you have different memories at different times of day, you are, in effect, different people.

Wonderful. My God what a premise. And the writing lives up to it. I can’t wait for the next season.

That’s it for now. Be seeing you.

A rich potpourri, comme d’habitude. But a bit unfair - you make it tough to decide which of your themes to respond to among so many!

Let me focus on the valuable post you linked us to on the virtues of using history to make policy. The author suggests: “History is not a good in itself: it must be rigorously evaluated and applied, precisely why professional historians are needed”.

I agree, but only up to a point. History feels similar to risk management, in that we need professional advisors on the topic, but if the discipline is seen to be the preserve of a handful of boffins and not a responsibility or a skill set for the rest of us, the experts will get ignored at the most critical times by those ignorant of their craft. So we have to consider how can we make most people in organizations smart consumers of history who can then apply that knowledge constructively.

It might be interesting to train emerging leaders to do some research into why their organization’s longstanding capabilities, standards and processes came to be. What happened back then to which those practices seemed a useful response? What is or isn’t different now?

I particularly wonder whether something could be done to challenge the politicians who want to slash “red tape”, typically meaning regulations that (today) seem more of an irritation than they are worth. Could the politicos first be required to go back into the history of why the regulation was first devised? What problem was it an attempt to solve? Why should that problem no longer concern us or is there a more efficient solution now available? Under what circumstances might the de-regulator agree we need to re-regulate? Walkerton comes readily to mind…

Hoping that you have a wonderful trek - our annual trips to Nova Scotia via New England became a huge part of our family lore. As for different priorities, the complete recordings of Harry Potter by Jim Dale were the perfect antidote to such dilemmas!

Good post and happy hunting for new photos of old presidents. I particularly appreciate your understanding of the immense and irreplaceable value of archives. Happy trails.