In late 1906, Henry Ford started a new project.

Ford directed staff to build a new room in the main factory of his Ford Motor Company. The room needed a door big enough to drive a car through, Ford said. And put a good lock on the door. Only essential staff would be allowed inside. No peeking permitted.

When the room was ready, a small team assembled. Ford told them they were going to design a new car. From the ground up.

Intent on keeping the car as lean, light, and uncomplicated as possible, they worked through the components — the engine, the transmission, and all the rest. Ford sat in a rocking chair for long hours, watching everything, speaking up when needed. Sketches became designs. Designs became blueprints.

Scale models were built and Ford handled them, looked at them from every angle, played with them. The team calculated performances, revised designs, built new models.

Parts were machined and tested. Components were cast and assembled. More testing, more modification.

Ford was always present, always watching and thinking.

Central to the design was a new steel made with vanadium. It was lighter than other steels. Ford wanted his car to be made with this new steel so he found an Englishman who had pioneered it and an Ohio foundry that could make it.

A prototype was built. They drove it for miles then took it back to the design room, disassembled it, inspected the parts for wear, and drew conclusions. They reassembled the car. More testing.

Ford oversaw everything. He drove the car for hours. “Mr. Ford would not let anything go out of the shop unless he was satisfied that it was nearly perfect as you could make it,” a mechanic recalled. “He wanted it right.”

This went on for two years.

The result was the Model T.

First put on sale in early 1909, the Model T was an immediate hit. Sales escalated year after year. The Ford Motor Company grew with astonishing speed but still it couldn’t keep up with demand.

Ford would ultimately make and sell 15 million “Tin Lizzies.” The car became “as common as horseflies and as American as apple pie,” in the words of Ford biographer Steven Watts (whose excellent biography of Henry Ford, The People’s Tycoon, I am relying on here). By 1920, American roads were flooded with automobiles and almost half were the car designed in that little room.

The Model T elevated the Ford Motor Company from one of many car makers to the colossus of the industry. It made Henry Ford the most revered figure in the United States. It changed America and the world.

On a list of the most successful new products in history, the Model T must rank near or at the top.

Why was it such a success?

It’s easy to credit the extreme care and rigour of the process that developed the car, the wisdom of designing it from the outset to be as simple as possible, and the discovery of the new, lighter steel. Henry Ford and his engineers did all they could to make a magnificent car that cost far less than most cars of the day. And that’s what they did.

But as true as all that is, it misses something profoundly important — a step that came well before the Model T’s design and development. Without this step, the Model T would probably not have become what it was, and made history.

It’s a step that has been done well in countless big, ambitious, complex projects that paid off handsomely, as Bent Flyvbjerg and I illustrate in How Big Things Get Done. The architecture of Frank Gehry. The biographies of Robert Caro. The iPod and many other Apple products. And much of what Amazon does.

It is asking a question, the question Frank Gehry asks each client who walks in his front door.

“Why are you doing this project?”

Three years before Henry Ford ordered the creation of the little room for his next project, he founded the Ford Motor Company. It was 1903. Car makers were springing up at a relentless pace. Buckmobile. Stevens-Duryea. Pierce-Arrow. Greenleaf. Sandusky. There were countless other names, most now long forgotten because most of these new companies lasted only a few years.

Some people got into the car business because the technology was new and exciting. More were enticed by money. In 1903, cars were novelties sold mostly as luxury goods to wealthy owners who drove them for amusement and to impress friends. As usual with luxury good sold to the rich, profit margins were fat.

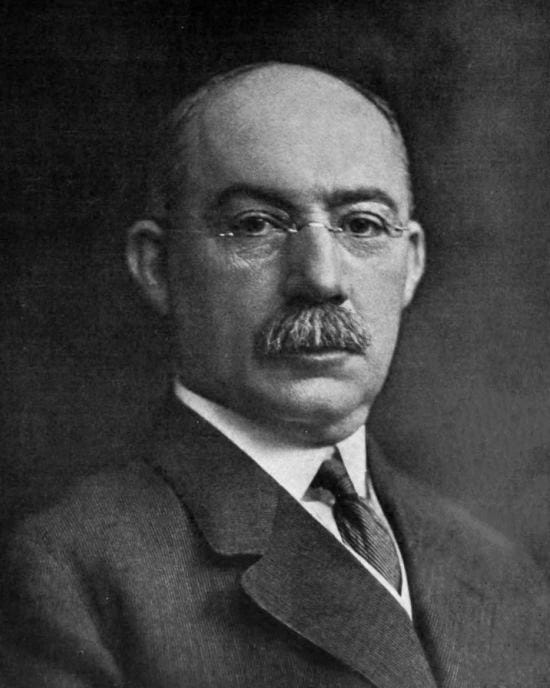

To launch Henry Ford’s new company — which was not his first — Ford had the backing of a wealthy investor, Alexander Malcolmson, a 38-year-old Scottish immigrant who had made his fortune as a coal dealer. Malcomson expected Ford to do what everyone was doing — make expensive cars for the rich and reap those fat profit margins.

That’s what Ford mostly did, at first. But Ford came from modest circumstances and he had a democratic streak that chafed at this direction.

Ford wanted to make a car that more people could buy. So in the company’s earliest years, it also produced cheaper models.

The Model B, the rich man’s car, was heavier and more powerful. It sold decently but unspectacularly. The Model A — succeeded by the Model C and the Model F — were more in line with Ford’s thinking. They didn’t have the fat profit margins but they sold much better than the Model B.

Ford kept thinking.

In that era, cars were built by teams of craftsmen who did more than merely assemble identical parts. They worked with the parts, filing and shaping them, getting them to go together just so. It took skill. And while the cars they built were similar, the application of the craftsman’s skill meant they were not truly identical.

Ford believed cars could be build at much lower cost by pushing manufacturing toward more precise machining of parts in order to produce truly identical cars.

When you get to making the cars in quantity, you can make them cheaper, and when you make them cheaper you can get more people to buy them. The market will take care of itself…. The way to make automobiles is to make one automobile like another automobile, to make them all alike, to make them come through the factory just alike; just as one pin is like another pin when it comes from the pin factory, or one match is like another match when it comes from the match factory.

In Ford’s mind, a much less expensive car offered a far more promising business model. Inexpensive goods sold at low prices may have paper-thin margins but there are millions of ordinary people and millions of potential sales. Millions of sales with thin profits beats the pants off selling a handful of goods with fat profit margins. That’s basic math.

But however cheap a car may be, why would ordinary people want to own one?

In hindsight, that’s not a question we would ask, but at the beginning of the 20th century, people got to and from work, and went about their daily lives, without cars, as they always had. So even if Ford could dramatically cut the cost, why would millions of ordinary people with little disposable income pay $500 — more than $15,000 adjusted for inflation — to buy what had only ever been a novelty, a plaything, a rich man’s toy?

Ford knew why.

In his statements and his advertising, Ford noted the utility of a car. Get to and from work. Move people and goods. Go when you choose and move at your own pace. But Ford understood that the lives of ordinary people were changing.

In the mid-19th century, a factory worker might put in a grinding 70 hours a week. Add in time getting to and from the factory and exhausted workers had little or no free time, Sundays aside. But as manufacturing expanded and grew increasingly efficient, pay rose and — more importantly — hours of work declined.

The change was summed up in one word: “weekend.”

Originally spelled, “week-end,” the word came from the industrial north of England, where it referred to the Sabbath, then Saturday afternoon and Sunday. Until the turn of the century, it appeared only rarely in American newspapers. Then it exploded. One database shows it was used 26,872 times in 1906 alone.

Increasingly, ordinary people had leisure time.

Henry Ford saw this the change and understood its significance far earlier than most.

I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family but small enough for the individual to run and care for…. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one — and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.

Utility and leisure ensured demand. Ford just had to figure out how to make a good car far more cheaply than ever before. Do that, Ford believed, and he would sell not the thousands of cars that successful manufacturers were turning out in a year. He would sell millions.

Ford’s thinking persuaded some of his key partners, notably James Couzens, Ford’s Canadian business manager who was so critical to the company’s success in its first decade. But Ford couldn’t change Malcolmson’s mind, and Malcolmson was the biggest shareholder.

With a series of deft corporate maneuvers, Ford and Couzens ousted Malcolmson, freeing Ford to pursue his vision.

Ford ordered the little room built and got to work designing the Model T. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Now, let’s go back to that question: Why was the Model T such a success?

Yes, the work of Ford and his team in designing and developing the car was superb. They crafted a fantastic car.

But if they had crafted a fantastic car people didn’t want, it would have been a fantastic flop. Business history is littered with fantastic flops.

What was absolutely essential to the success of the Model T is that Ford had perfect clarity about his goal and what the new car had to be to achieve it. And he had that clarity before he and his team drew their first sketch.

During the years in which Henry Ford founded his company and designed the Model T, an engineer and business consultant named Henry Gantt developed the “Gantt chart,” the classic method of laying out and managing projects. In a Gantt chart, tasks that must be completed are placed in a series of boxes starting on the left and flowing to the right. The project’s completion is the last box on the right. There are lots of more-modern variations of Gantt’s invention but the basic idea remains the same today.

In How Big Things Get Done, Bent Flyvbjerg and I argue that in order to succeed, project managers need to manage from left to right — but they must “think right to left.”

That means the project must start with the final box on the right. That’s the end. The goal. Not merely the completion of work, but the achievement of the good things the project promises to deliver.

Only when there is perfect clarity about what is in that box should planning begin. And for the duration of the project, the project manager must constantly bear in mind what is in that final box. That goal informs and guides everything else.

That is precisely what Henry Ford did with the Model T.

As Ford himself put it:

Ordinarily, business is conceived as starting with a manufacturing process and ending with a consumer….

But what business ever started with the manufacturer and ended with the consumer? Where does the money to make the wheels go around come from? From the consumer, of course. And success in manufacture is based solely on an ability to serve that customer to his liking….

We start with the consumer, work back through the design, and finally arrive at manufacturing. The manufacturing becomes a means to the end of service.

This explains why Frank Gehry’s question — “Why are you doing this project?” — is the indispensable starting point of every project.

If you develop an informed, thoughtful, and crystal-clear answer to that question, you will know exactly what goes in the box on the right.

Picture Henry Ford telling you to build that little room where they are going to design a new car. You ask him the key question: “Why are you doing this project?”

Ford: “We are going to give ordinary people a car that is both practical and a pleasure to drive in their growing leisure time.”

Notice that the answer is not “we are going to use this cool new steel to make a new car.”

Nor is it “we are going to make an excellent car at a dramatically lower cost.”

Those are not ends. Those are the means to the end. They come later.

What was Ford going to do for customers? That’s what is in the box on the right.

Focusing on the goal first is a timeless idea. “You’ve got to start with the customer experience,” Steve jobs famously said, “and work backwards to the technology.” The language is more modern but that’s no different than what Henry Ford said 80 years earlier.

At Amazon, “working backwards” is not only a guiding concept, Jeff Bezos created a formal process to ensure it is the foundation of every project.

Bezos noted that after a project at Amazon is all but done, the very last task is the writing of a press release (PR) and a “frequently asked questions” document (FAQ). These documents are written for ordinary people who don’t know anything about the project so they use plain, simple, clear language. And they explain excellent new thing Amazon is delivering to its valued customers.

So, working backwards, Bezos made that last task the first task of every new project at Amazon.

As Bent and I wrote in How Big Things Get Done:

To pitch a new project at Amazon, you must first write a PR and FAQ, putting the goal smack in the opening sentences of the press release. Everything that happens subsequently is working backwards from the from PR/FAQ, as it is called at Amazon…. [Written in plain language] flaws can’t be hidden behind jargon, slogans, or technical terms. Thinking is laid bare. If a thought is fuzzy, or ill-considered, or illogical, or if it is based on unsupported assumptions, a careful reader will see it.

Projects are pitched in a one-hour meeting with top executives. Amazon forbids PowerPoint presentations and all the usual tools of the corporate world, so copies of the PR/FAQ are handed around the table and everyone read it, slowly and carefully, in silence. Then they share their initial thoughts, with the most senior people speaking last to avoid prematurely influencing others. Finally, the writer goes through the document line by line, with anyone free to speak up at any time.

These discussions are detailed and intense. Afterward, the person proposing the project considers the feedback and drafts another version of the PR/FAQ. This process may repeat many times before a project gets the green light. In this way, Amazon ensures that the goal of any project is as carefully considered and clear as Henry Ford’s was when he started to design the Model T.

Maybe this all strikes you as common sense. Perhaps it is. But I assure you that, however sensible it may be, it is not common.

Big projects often start without the careful consideration of the goal that Henry Ford brought to the designing of the Model T — and that missing piece can cause a host of problems, from scope creep, to teams working at cross-purposes, to a project that doesn’t deliver the benefits it is expected to.

Why do projects start without a clear, informed goal? It can happen for a number of reasons, the most basic being psychological. Quickly sizing up a situation, drawing conclusions about what it means, and settling on the first course of action that promises to effectively respond to it is natural human decision making. Why waste time talking about the goal when the goal is “obvious”? The get-to-work culture that is common in business — a culture in which research and planning are denigrated — rewards this sort of peremptory decision making and punishes those who wish to slow down and think. Few people in business get the years to ruminate that Henry Ford had.

There’s also the danger of falling in love with the means, which can even trip up executives who know the importance of starting with clarity about the end. In How Big Things Get Done, Bent and I cite Apple’s Power Mac G4 Cube, which was released in 2000 but looks, even today, like the super-cool embodiment of everything Steve Jobs loved about technology and design. And that was the problem. It was as if Henry Ford had been so smitten with vanadium steel and precision engineering that he designed a whole car around them and simply assumed the customer would love it as much as he did. The Model T may have bombed. As the G4 did.

It takes conscious, deliberate, determined focus to start a project with the box on the right and maintain that focus to the project’s completion.

Without that, there is likely to be trouble. With it, you have a shot at changing the world.

Good. I appreciate your articles, even if I don't always agree. This article makes many good points. Talking about personal vehicles, the problem that the auto/EV industry today has, is their product is NOT actually functionally equivalent to ICE vehicles, and for most of the harried middle class, EVs have LOWER utility than ICE cars. Whish is why the middle class is not yet buying them en masse.

Tata Motors hoped the tiny Nano would be for India what the Model T was for the USA. They succeeded in designing and building the most inexpensive new car in the world.

...which is exactly why it flopped.

The company overlooked an important factor: newly middle-class Indians saw new cars as status symbols and didn't want the stigma of owning a "cheap" vehicle. They were willing to save up or pay a bit more to get a larger (and presumably safer) car instead.

There's a lesson there about being one of the first countries to have an emerging middle class, and one which is only building up one now.