Hitler And The Study Of History

Why do popular misperceptions of history persist? In part, it's bad teaching.

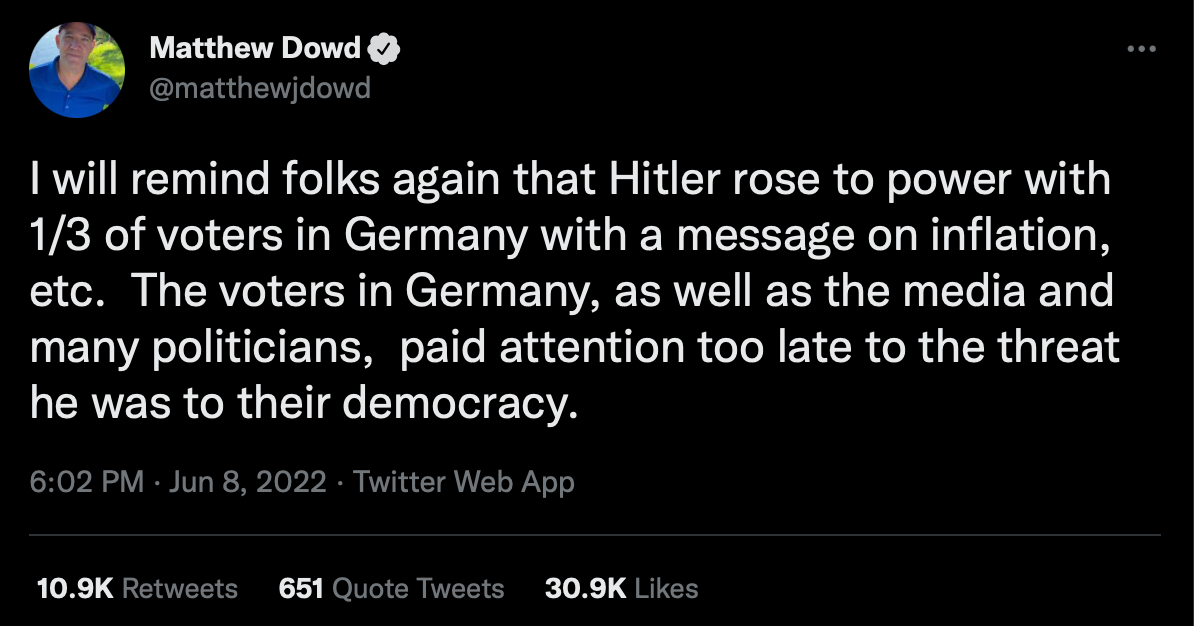

On Twitter yesterday, I came across a viral tweet about the rise of Nazi Germany and American politics today.

I’m all for being vigilant in defence of democracy but this tweet is, I’m afraid, a classic of a certain genre. I want to unpack that first. Then talk about why misunderstandings like this persist.

Notice what’s highlighted here: Hitler rose to power “with a message on inflation, etc”

This is a reference to the major inflation that struck Germany in 1921 and 1922 and the hyperinflation that exploded in 1923.

Bills were printed in vast quantity, in escalating denominations — during the worst of the hyperinflation, Germany was printing 50 trillion mark notes — until even piles of cash were effectively worthless.

Finally, starting in late 1923, the introduction of a new currency in strictly controlled denominations and numbers smothered hyperinflation like a raging fire deprived of oxygen.

The period of hyperinflation was a wonderland if you were visiting Germany with foreign currency in your wallet, and it was a delight if you were deeply in debt. For everyone else, it was a terrifying experience. And if you had savings, you were hit worst of all: Every pfennig was gone.

The trauma of that period was seared so deeply into German culture that it’s still there. Germans obsess over savings and tremble at the thought of inflation. This obsession has real consequences. In the crisis between 2009 and 2012, when deflation was the greater threat, the Weimar hyperinflation was often cited in economic policy debates in support of policies that — many economists argue — worked to the detriment of Germany and other European countries. But set that aside for now.

Given how traumatizing the hyperinflation was, it’s perfectly reasonable to think it radicalized much of the German population, empowering the Nazis and bringing Hitler to power. And lots of people do, in fact, think that. Like the person who wrote the tweet above, apparently.

But there’s a problem: Hyperinflation ravaged Germany in 1923. By 1924, it was over. And in the following years, the Germany economy was stable and robust. The second half of the 1920s was actually a relatively prosperous time in Germany. Only in 1930 did the economy nosedive into the Great Depression. That’s when unemployment exploded. Not because of inflation. On the contrary, the Great Depression was deflationary, meaning prices declined.

And there’s another problem: In 1923, the year of the hyperinflation, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party attempted to capitalize on the turmoil by staging the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich. They were defeated in a pitched battle. The survivors were arrested and Hitler was imprisoned.

Far from bringing Hitler to power, 1923 was the Nazis’ annus horribilis.

When Hitler was released from prison at the end of 1924, the Nazis weren’t even a legal party. After Hitler promised to seek power only by democratic means, the ban on the party was lifted, but it did the Nazis little good. The improvement in economy had cooled the political atmosphere and radicals like the Nazis were on the outs. (In 1928, they got 2.6 percent of the vote.) And they stayed there … until 1930 and the Great Depression. When unemployment surged, so did the Nazis’ electoral success, culminating in Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor in 1933.

This simple chronology of events is enough to see how wrong it is to draw a straight line from the hyperinflation to the rise of Hitler. If anything, it suggests the real culprit was deflation.

And yet, people routinely blame inflation for the rise of Hitler. Even in Germany. Especially in Germany. One study of the German public found “Germans do not distinguish between hyperinflation and the Great Depression, but see them as two dimensions of the same crisis. They conflate Weimar economic history into one big crisis, encompassing both rapidly rising prices and mass unemployment.” The craziest part? The people who are more likely to make this serious mistake are “more educated and politically interested Germans.”

This is not to say that the hyperinflation in 1923 did not contribute at all to the rise of the Nazis. It does, however, show that drawing a straight line from one to the other — “this caused that” — makes little sense. And we should pay more attention to the dangers of deflation and mass unemployment. (Historians continue to debate the extent to which the experience of 1923 contributed to the disaster of 1933. A recent data analysis came down strongly on one side: “I find no connection between the traumatic experience of hyperinflation and the electoral success of the Nazis nearly a decade later.” How is that possible? Some have suggested that the erasure of savings by the hyperinflation was not as great as thought because savings had already been devastated by the crushing years that preceded it. Even calamities can blur if you suffer enough of them.)

So now on to the second task: How do misunderstanding like this persist even though the basic chronology of the period is enough to clear them up?

There are many factors at work (to borrow the favourite cliche of historians) but one that I want to highlight involves that word — “chronology.”

There was a time, in the not too distant past, when students in history classes were instructed to memorize a list of facts and dates. That’s it. Fact and dates, facts and dates. What happened in 1914? 1918? 1923? 1933? And so on. Get a good mark on the quiz and you have mastered history.

Mention this to history teachers or professors today and they will roll their eyes. And rightly so.

This isn’t serious history. Memorizing all the Kings of England — which was standard in history classes throughout the British Empire, then the Commonwealth — may help you if you are ever a contestant on Jeopardy. But it gives you very little grasp of the past. At best, it’s some raw material you can use when you get serious about studying history.

But this view can be taken too far. And all too often, it is.

In high schools and universities, it has long been commonplace to put students in classes which are not organized chronologically, where little effort is made to lay out basic facts as plainly as I did above, and the mastery of those facts is not considered one of the core goals of the class.

Instead, history is organized around in themes and students are urged to think critically. That is wonderful for students who have already mastered basic facts and chronologies. For those who haven’t, it’s in invitation for confusion, muddle, and bluffing. And a good reason to never take another history class if you can avoid it.

It also means easily corrected but popular misunderstandings like "hyperinflation led to the rise of the Nazis” continue to flourish. These degrade popular discourse. And occasionally — as in recent German economic policy — have serious, immediate consequences.

But never mind me. After I tweeted some of the preceding thoughts, historian Peter Schulman directed me to a compilation of interviews and writing of the historian Tony Judt, who was thoughtful, deeply informed, and a dazzlingly clear communicator. Judt was masterful on this point.

So I’m just going to shut up and give him the floor. (The speaker in italics is historian Tim Snyder.)

As per usual, Dan provides brilliant insight.