How bad is it?

Depends on the benchmark. Here's one that will make you feel a little better.

Judgements about the present tend to be relative.

The average American in 1960 was much better off than ten or fifteen years earlier, so he considered himself blessed in 1960. But if we were to remove the income, house, car, clothing, and consumer goods of the average American today, and replace them with the average American’s in 1960, today’s average American would think he had suffered a calamity.

What you see depends on what you compare it to.

The first point of comparison any of us has is the immediate past, which we experienced personally. For those unfamiliar with history, that first comparison is likely to be the last. But those who study history discover it contains a plethora of benchmarks.

History’s benchmarks are handy at any time, but living in the Trump era they are something of a psychological necessity: Knowing that other eras have been far more appalling — more squalid, corrupt, immoral, incompetent, bigoted, dangerous, violent, and uncertain — is like wrapping your arms around your childhood teddy bear. It may not do any practical good. But it calms the mind.

So today I thought I’d offer you a remarkable benchmark.

If you think things are bad and getting worse (stage whisper: I agree) then read on. And file this away for use the next time you’re watching the news and you need a hug.

Long before he became a famous Austrian writer, Stefan Zweig was the world’s luckiest baby.

Born in 1881, Zweig’s mother came from a rich banking family. His father was a wealthy textile manufacturer. The Zweigs lived in Vienna, which was at the height of its imperial splendour.

Little Stefan Zweig grew up in the world of Gustav Klimt, art nouveau, grand balls, cavalry officers in dashing uniforms, and confidence that things would only get better.

As he wrote in his autobiography:

At the end of this peaceful century, a general advance became more marked, more rapid, more varied. At night the dim street lights of former times were replaced by electric lights, the shops spread their tempting glow from the main streets out to the city limits. Thanks to the telephone one could talk at a distance from person to person. People moved about in horseless carriages with a new rapidity; they soared aloft, and the dream of Icarus was fulfilled. Comfort made its way from the houses of the fashionable to those of the middle class. It was no longer necessary to fetch water from the pump or the hallway, or to take the trouble to build a fire in the fireplace. Hygiene spread and filth disappeared. People became handsomer, stronger, healthier, as sport steeled their bodies. Fewer cripples and maimed and persons with goiters were seen on the streets, and all of these miracles were accomplished by science, the archangel of progress. Progress was also made in social matters; year after year new rights were accorded to the individual, justice was administered more benignly and humanely, and even the problem of problems, the poverty of the great masses, no longer seemed insurmountable. The right to vote was being accorded to wider circles, and with it the possibility of legally protecting their interests. Sociologists and professors competed with one another to create healthier and happier living conditions for the proletariat.

Small wonder then that this century sunned itself in its own accomplishments and looked upon each completed decade as the prelude to a better one. There was as little belief in the possibility of such barbaric declines as wars between the peoples of Europe as there was in witches and ghosts. Our fathers were comfortably saturated with confidence in the unfailing and binding power of tolerance and conciliation. They honestly believed that the divergencies and the boundaries between nations and sects would gradually melt away into a common humanity and that peace and security, the highest of treasures, would be shared by all mankind.

Zweig studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and wrote novels, novellas, and historical studies in his spare time. In 1904 he earned his doctorate. His life as a wealthy intellectual continued to unfold precisely as expected.

Until 1914.

That year, a driver made a wrong turn, an assassin seized the chance to murder the heir to the Austrian throne, and the world went mad.

In his autobiography, written in 1941, Zweig recounted, “I was born in 1881 in a great and mighty empire, in the monarchy of the Habsburgs. But do not look for it on the map; it has been swept away without trace.”

In the 1920s, Zweig’s career soared as his writing enjoyed international success and he became friends with luminaries such as Sigmund Freud and Richard Strauss. But the rump state of Austria was unstable and impoverished.

The Great Depression followed. In 1933, the Austrian expat Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. In 1934, a Catholic-fascist government took control of Austria. (Annexation to Germany would follow in 1938).

And for all his Viennese polish and global fame, Stefan Zweig remained, in the eyes of the rising powers, merely a Jew. So in 1934, Zweig and his wife fled to Britain.

In 1940, with Britain at war and the Nazis rolling across Western Europe, Zweig fled again, across the Atlantic to America, and then continued on to a German-speaking community in Brazil.

It was there that he wrote his autobiography.

Against my will I have witnessed the most terrible defeat of reason and the wildest triumph of brutality in the chronicle of the ages. Never—and I say this without pride, but rather with shame—has any generation experienced such a moral retrogression from such a spiritual height as our generation has. In the short interval between the time when my beard began to sprout and now, when it is beginning to turn gray, in this half-century more radical changes and transformations have taken place than in ten generations of mankind; and each of us feels: it is almost too much!

As Zweig was writing those words, Hitler ruled Europe from the Atlantic to Moscow, while Germany’s ally in Asia, Japan, steadily expanded its power. It seemed the world would, as Churchill warned, “sink into the abyss of a new dark age, made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.”

Looking back on his life, Zweig was staggered by what his generation had already lived through.

It was reserved for us to participate to the full in that which history formerly distributed, sparingly and from time to time, to a single country, to a single century.

At most, one generation had gone through a revolution, another experienced a putsch, the third a war, the fourth a famine, the fifth national bankruptcy; and many blessed countries, blessed generations, bore none of these. But we, who are sixty today and who, de jure, still have a space of time before us, what have we not seen, not suffered, not lived through? We have plowed through the catalogue of every conceivable catastrophe back and forth, and we have not yet come to the last page.

The day after Zweig completed his autobiography in early 1942, he and his wife swallowed an overdose of barbiturates and held hands as they died.

So, are you worried about the trajectory of the last decade? Think your generation got a raw deal? You have a point.

But you should also give a little consideration to the benchmark of Stefan Zweig.

Incidentally, if and when the times turn sweet again, Zweig’s description of the world he was born into, and believed would go on forever, should also be kept on file as a warning against the complacency which settles in when bellies are full and the sun shines.

But that probably won’t be necessary for a while.

Obiter dicta

1/ On Republicans.

It’s often said today’s Republican Party is, despite its frequent appeals to nostalgia, ignorant of history. I think that’s not entirely accurate. It’s closer to the mark to say today’s GOP is determined to think whatever makes Democrats look bad is true, and that includes ignoring history. Or rewriting history. Or turning history on its head.

A case in point.

In this post, Paul Krugman copies a GOP fundraising pitch which includes some GOP boilerplate: “When we were growing up,” it reads, “our cities were beacons of American exceptionalism. But thanks to Democrat politicians, they’re now rat and feces infested gang headquarters for illegal immigrants.”

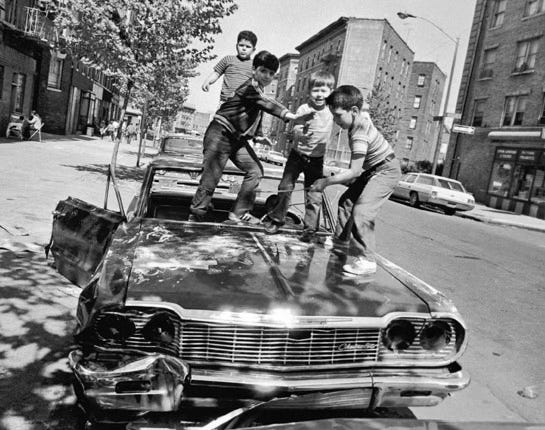

Krugman has various stats from recent years — using the 1990s as the baseline — showing that’s nonsense. But maybe the GOP was referring to an earlier golden era for American children? Let’s be generous and go further back.

I’m 57. Born in 1968. Grew up in the 1970s.

Were American cities shining “beacons” in the 1970s?

No. If you saw a fire burning in American cities it was probably a car set ablaze for the insurance money.

The phrase “urban decay” came into its own in the 1970s. The worst city of the lot was New York, which suffered unprecedented economic and political crises. It teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Even physical collapse. New York was “Drop Dead City.” Its decline into sleaze, filth, and crime became the backdrop for a parade of movies, including Taxi Driver (“You talking to me?”), while its bleak future inspired a long list of dystopias, like Escape From New York, which depicts the city as a walled-off dumping ground for the worst criminals — a place so dangerous that even that bad-ass Snake Plissken barely escapes with his life.

So over the past half century, did American cities, led by Demoncrats, fall from glorious heights to become today’s “rat and feces infested gang headquarters for illegal immigrants”? No. In fact, if we must generalize so broadly, their trajectory was the reverse.

Now, to be fair, the 1970s were an unusually grim era for America’s cities. So what happens if we go a little further back?

It’s true the cities did boom in the 1950s. But how old would you have to be to say “when we were growing up in the 1950s”? Far older than the overwhelming majority of Americans. In fact, you’d have to be as old as Donald Trump. And that’s old. Trump was born in 1946. His cohort is entirely in its seventies and eighties.

So why would GOP fundraising use that perspective? In part, I’m sure, it’s rational calculation. Most Americans know little about the decades before they were born beyond the images they’ve absorbed from ads and movies — and the image of an Edenic America before the 1960s is a potent one in American culture, as is the image of growing up in that era, even for those born decades too late for that. So you allude to “when we were growing up” without specifying when that was to allow the audience to read in those images, and feel loss even though they have lost nothing.

But I also think this runs deeper than calculation.

Today’s Republican Party has been absorbed, Borg-style, by Donald Trump, so Trump’s assumptions and obsessions are now the GOP’s assumptions and obsessions. And Trump is very much a product of his time.

In his twenties, Trump started inventing the character he has played ever. That was in the 1970s. In New York City. And the worldview Trump developed and articulated then did not evolve as the years passed. In fact, it was frozen in amber. Any historian familiar with the language of urban decay in that era recognizes everything Trump says about urban decay today. It’s identical. Word-for-word. When Trump talks about American cities today, what he says sounds exactly like what a rich young asshole would say about American cities in the 1970s.

That’s a big reason why, in the world imagined by the Republican Party, New York City is forever the urban hell Snake Plissken barely escapes with his life.

2/ We’ll meet again, Maine.

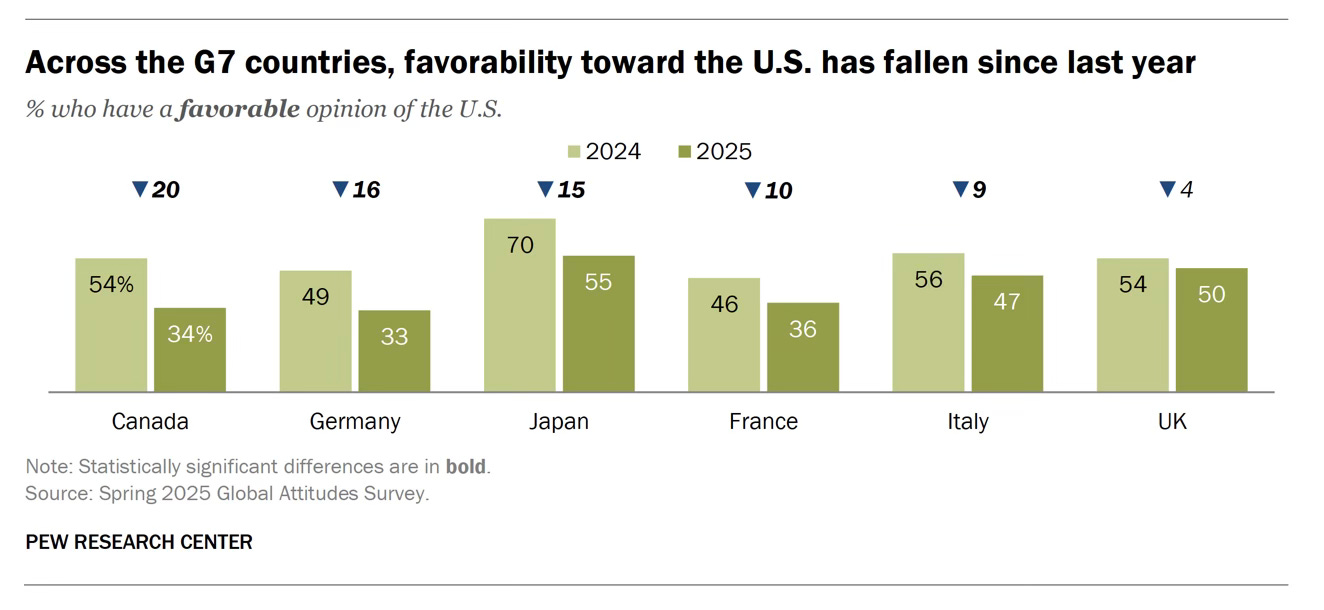

One of Donald Trump’s biggest lies (this is no small claim) is that under his leadership respect for America has soared around the world.

As usual, the reality is the opposite of what Trump says. America’s standing in the world is in free-fall. And nowhere is the destruction of America’s old friendships happening faster than in my own country, Canada.

This antipathy is not only appearing in public opinion polls. A remarkable number of Canadians are boycotting American goods and services and cutting back on travel to the United States.

That hurts us, believe me. We like bourbon. (I do, at least.) And we love spending our snow pesos in Vegas and Florida. But the President of the United States repeatedly insulted Canada, a country that has never been anything but a loyal friend to the United States. He tore up a trade agreement he personally negotiated and signed, demonstrating that his word is, to borrow a phrase from John Nance Garner, not worth a bucket of warm piss. And he has threatened us with economic ruin if we don’t comply with his demand to erase our country and join the United States.

I’m sure any person with a cluster of functioning brain cells would understand why most of us take that personally.

Or so I would have thought.

The US ambassador to Canada recently defended Trump calling Canadians “mean and nasty” on the grounds that Canadians had responded to Trump’s gangsterism with something stronger than a pained smile and “please sir, may we have another?” Apparently, to the ambassador, tearing up trade deals and threatening an allied nation is boys being boys but refusing to drink American wine is downright hostile. I understand that representing the most ignorant, thuggish, incompetent president in American history is a tough gig, but honestly, is it too much to expect an American ambassador to a G7 country will demonstrate even a touch more wit and finesse than the short-fingered vulgarian currently staining the White House sheets orange?

But let’s set all that aside. Here, I want to be very clear about who is angry at whom.

Canadians may be boycotting American booze and American casinos, and we are certainly mad as hell at Trump and the billionaires and cowards (I repeat myself) enabling Trump’s assault on American democracy, America’s allies, and the world order America built. But I’m confident I speak for most Canadians when I say we are not angry at most Americans and we hate that the boycott may hurt Americans who are entirely innocent of, or even opposed to, Trump’s thuggery.

We want to visit and spend our pesos. We really do.

I live in Ontario and my family travels most summers to New Brunswick to visit my wife’s family. We often take the long way around, going south into Vermont, New Hampshire, then Maine. It’s beautiful countryside, the people are lovely, and the towns are full of history. I can’t say enough about Maine, in particular. I’ve never been anywhere with more antique stores per square mile, and poking through stacks of Americana looking for presidential bric-a-brac is my idea of August bliss. I have a 1932 portrait of FDR hanging on my cottage wall, along with medals commemorating Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, and a framed memorial poster for the slain William McKinley. They’re worthless. I treasure them.

I got them all from the same antique store in Skowhegan, Maine, a sprawling emporium on the main street across from a delightful bakery in an old bank. It’s called “The Bankery.” How frigging adorable is that?

I hope my point is clear: I am no anti-American. I am, in fact, an Americanophile. I love American history, the American constitution, and the portraits of American presidents hanging on my Canadian cottage wall. And I freaking love that antique store in Skowhegan. My abiding ambition in life is to land an Eisenhower portrait there one day. I’m sure I will.

But it won’t be this summer. We have a family wedding in New Brunswick this year. We’re taking the short route and staying well away from the border.

Because as much as I love August in Maine, I love my country more. And this boycott is the one way I — and tens of millions of my fellow Canadians — can tell that New York gangster to go to hell.

I hope our American friends understand.

In the meantime, naturally, you’re always welcome in Canada.

Just don’t make any “aboot” jokes.

I don't know what algorithm dropped your message in my in box but I am extremely grateful it did. It is shocking that my country finds itself here, antagonizing friends and cuddling dictators. While I see an unfortunate and long timeline of this madness, there is comfort knowing our shared humanity continues.

I met a man from Beirut who told me about the wonderful life he had growing up in Lebanon — a prosperous multicultural society where everyone got along — until it was destroyed by civil war, and it has not recovered since. My takeaways from that story and this one: enjoy what is good in life and be aware of how fragile goodness is and guard against its destruction.