Most American presidents slowly drift out of public memory. For some, that’s a shame. Presidents like Dwight Eisenhower deserve more than their small and shrinking presence. But for others, it’s a mercy.

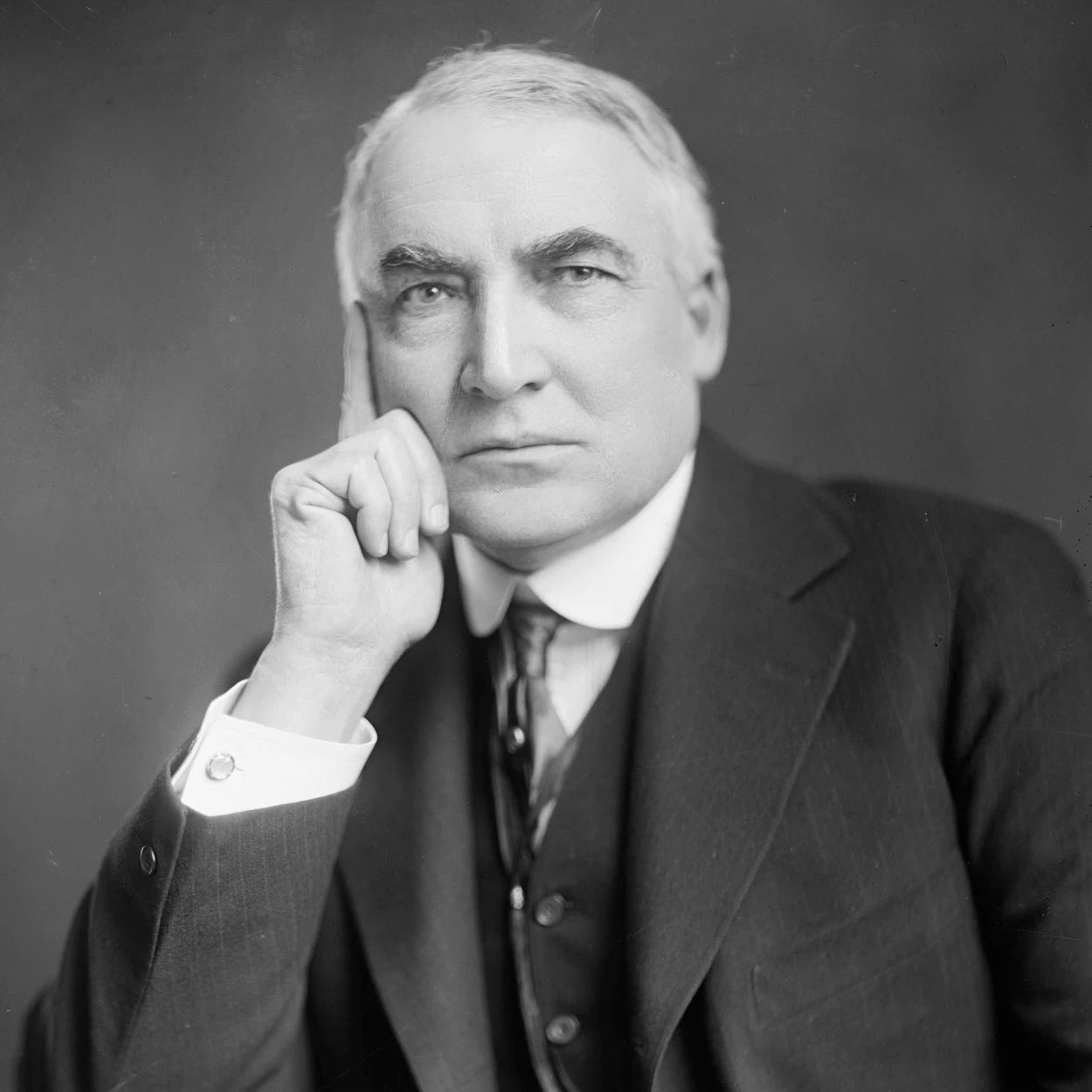

Consider Warren G. Harding.

Chances are you know nothing about Harding, or if you do know something, it’s not good. He routinely appears at or near the bottom of historians’ rankings of presidents. Not because he made bad judgements with catastrophic consequences, like a certain Texan named Bush. Or because he was dangerously impulsive, like a more recent occupant of the White House. Harding was an awful president because he was a small man, bereft of vision, who put smaller men in office. And he looked the other way as his administration became a carnival of corruption.

Really, after becoming president in 1921, Harding did only two things right: First, he confided that “I am not fit for this office and should never have been here.” Then, in 1923, he dropped dead of a heart attack at the age of 57.

But in politics, as in comedy, and life, timing is everything. And Harding’s exit stage left was superbly timed. The corruption of his administration was only starting to come to light, and so, by dying, Harding dodged the difficult decision of whether to resign, decline to run for re-election, or fight an uphill battle for a job he never particularly wanted. He also ducked out before it was revealed he had multiple mistresses. And a love child. And had used a closet in the Oval Office for unpresidential conduct. And had named his penis “Jerry.”

Other unpopular presidents — Nixon, Hoover — have their defenders. Not Harding. It is all but universally agreed that he was a terrible chief executive.

So what follows here is stunningly ambitious. Or perverse, if you prefer.

In this post, after first conceding that Warren G. Harding was a truly terrible president — he was, there’s no dispute — I will argue that Harding may have done more good than any other.

That’s because Warren G. Harding played a critical role in saving America and the world from Adolf Hitler.

Now, if you’re familiar with the chronology of events in the first half of the 20th century, you may think that’s bonkers. There is no connection between Harding and Hitler. Their time on this earth didn’t even overlap, at least not in the years that matter. Thus it would seem impossible for Harding to have had a hand in the fight against Hitler, much less a decisive one.

So let’s start by reviewing that chronology on the American side:

Warren G. Harding became president in 1921 and died in 1923. Harding was succeeded by his vice president, Calvin Coolidge, who easily won the 1924 election.

In the years following, the American economy boomed — the good times were often called “Coolidge prosperity” — and Coolidge was all but guaranteed re-election in 1928. But Coolidge shocked the nation by announcing he wouldn’t run again.

His commerce secretary, Herbert Hoover, seized the moment, took the Republican nomination, and became president in 1929. A little more than half a year later, Coolidge’s decision not to run turned out to be the smartest move in American political history — as the stock market crashed and the United States plunged into the Great Depression. Hoover worked as energetically as the economic orthodoxy of the day allowed — it mostly called for balanced budgets, the gold standard, and waiting — but to no avail. Disaster turned to catastrophe. The whole country seemed to be on the edge of collapse when Hoover lost the 1932 election to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Roosevelt’s New Deal — which FDR aptly called “bold, persistent experimentation” — shovelled enormous sums into public works programs and aggressively intervened in economic affairs to a far greater extent than ever before. A long, slow improvement set in until FDR prematurely scaled back in 1937 and the economy again slumped.

But at that point, Roosevelt shifted focus to international affairs because Japanese and German aggression was raising the risk of a terrible new war. The White House imposed an embargo on American oil sales to Japan, which was a huge blow to Japan given that the US was the world’s largest oil producer and Japan had no reserves of its own. And over the objections of a strong isolationist movement, the Roosevelt administration gradually ramped up support for Britain, particularly after Germany invaded Poland, sparking the Second World War, in September, 1939.

Finally, on December 7, 1941, Americans were dragged fully into the war when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States. And you know the rest.

Now let’s look at the chronology in Germany:

In 1923 — the year Harding died — Hitler led his Beer Hall Putsch in Munich. The Putsch failed and Hitler went to prison. Weimar Germany enjoyed six solid years of relative stability and prosperity, a period in which Hitler and his movement faded into obscurity. Only with the coming of the Great Depression in 1930 did the Nazis revive. And only in 1933 — a decade after Harding’s death — did the Austrian corporal become chancellor of Germany.

Comparing these two chronologies, there would seem to be no connection whatsoever between Harding and Hitler. Which makes it difficult, to say the least, to imagine anything Harding could possibly have done to save the world from Hitler.

And yet I am arguing precisely that Harding saved the world from Hitler. Because there is a connection between Harding and Hitler.

That connection is Henry Ford.

Stick with me. This will all make perfect sense. Eventually.

It’s hard to overstate what a colossus Henry Ford was by the time Harding became president in 1921. In the first decade of the century, Ford had designed the Model T. In the second, he had improved the efficiency of manufacturing so radically that the cost of the Model T plummeted and owning a car became, first, a reasonable aspiration of ordinary Americans, then a necessity. By the early 1920s, Americans could see that modernization was rapidly transforming the United States, and their lives, and they credited Henry Ford as the man most responsible.

In a poll asking Americans to name the most important figures in all of human history, Jesus came first, Napoleon second, Ford third.

Inevitably, there were efforts — grassroots and elite — to get the great man into politics. Write-in ballot drives. Clubs stumping for Ford. Editorials and letter-writing campaigns. They should have gone nowhere. Ford was was an awkward public speaker, had no interest in the “belch and bellow” of political rhetoric (to use Mencken’s phrase), and even less use for the horse-trading that was the daily stuff of democratic politics.

But Henry Ford shared America’s high opinion of Henry Ford. Henry Ford was brilliant. Henry Ford was a visionary. Henry Ford was sure he knew what was best for Michigan, America, and the world. And it would be selfish for him not to involve himself in public affairs.

Ford’s first foray into politics was nothing less than an effort to end the First World War. In 1915, when the United States was still neutral, Ford chartered an ocean liner and invited American anti-war activists to join him in sailing from New York to neutral Norway, where they would … do something or other to end the war. It didn’t work. On the voyage to Europe, the peace activists fought incessantly, the press dubbed the mission “the ship of fools,” and Ford did little but sulk in Oslo.

This experience might have put others off politics permanently but Ford was far too sure of himself for that. In 1918, at the urging of President Woodrow Wilson, Ford decided to run for Michigan’s open seat in the US Senate, so he let his name stand in both the Republican and Democratic primary races, with the expectation that he would win both. Without giving speeches, shaking hands, and kissing babies. It worked on the Democratic side. But a wealthy Republican spent spectacular sums and eked out a win in that party's primary. In the general election, Ford again refused to campaign and was again defeated by the thinnest of margins. (The man who beat him would eventually be investigated for violating campaign finance laws and resign in disgrace.)

Despite Ford having a political record that was now equal parts hubris and incompetence, calls for him to enter politics only grew in the early 1920s. And it wasn’t a mere Senate seat people wanted for Ford. It was the White House.

While Harding and Jerry were cavorting in the Oval Office, the “Ford For President” movement grew. Ford played coy. He refused to officially announce his candidacy, but he also pointedly refused to say he was not running, and behind the scenes he quietly encouraged his admirers to take up the cry for their hero.

It didn’t matter that Ford had no consistent party identification and refused to put his name to any policy platform, or even a coherent set of ideas. He was a classic populist, a mid-Western farmer at heart, an isolationist by temperament, and a Prohibitionist by conviction. He dismissed “experts” with a sneer. To Ford, gut feel got things done. That may have smacked of arrogance coming from someone else but Henry Ford was the man who doubled his workers’ pay, turned his company into a giant, and got fabulously rich. Millions of Americans thought Ford walked on water. And Americans were looking for a messiah. The economy was weak. Unemployment was high. One Congressman reported hearing poor farmers chant ‘when Ford comes’ — “as if they were expecting the second coming of Christ.”

As Ford surged to new heights of popularity, the scandals of the Harding administration started to surface. Ford could not have hoped for better circumstances to launch a bid for the presidency, whether as a Republican, a Democrat, or an independent.

That’s exactly when it happened. Warren G. Harding had a heart attack and died.

Awful luck for Ford.

But there was worse to come. The new president, Calvin Coolidge, may not have been a visionary or an outstanding administrator — to put it mildly — but he was a strait-laced New Englander with an unblemished reputation and the willingness to investigate and prosecute Republican colleagues. Coolidge quickly won Americans’ confidence. And became the prohibitive favourite for the 1924 election.

Ford’s window of opportunity closed. It never opened again.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how Warren G. Harding saved us from Adolf Hitler.

Yes, there’s a bit more to the story. To understand it, we need to look at who Henry Ford was. And what he likely would have done had he taken residence in the White House in 1925.

Henry Ford was fundamentally an autocrat. The Ford Motor Company was his empire. Ford was its Czar. He neither sought nor listened to expert advice or outside criticism. He ruled by decree. Those around him nodded often and vigorously.

Like all the best Czars, Ford was deeply paternalistic. To get the famous $5 a day salary, double the industry average, a worker had to agree to be monitored by the Ford “Sociological Department” and live up to its standards for behaviour and comportment — at work and home. The Department enforced these standards with unannounced inspections — at work and home. Cleanliness and hygiene. Cooking. Children in school. Personal finances. The Sociological Department combed all aspects of the lives of Ford’s workers to ensure they lived and worked as Henry Ford thought workers should live and work.

This wasn’t all as authoritarian as it sounds. The company also provided English lessons for new immigrants and instructions in home economics and safety. But the relationship Henry Ford had with his employees more closely resembled that of a stern but loving father and his children than that of employer and employees.

And Ford’s dreams of social engineering went far beyond that.

In the early 1920s, Ford pushed hard to get the federal government to sign off on a scheme of his that would have been one of the most ambitious in American history: On the Tennessee River, in Alabama, at a place called “Muscle Shoals,” Ford wanted to take over a hydroelectric development partially completed by the federal government during the First World War. Ford would expand its production of electricity. And build a gigantic new industrial city.

It would be a city like no other. Ford lamented the passing of the rural America he grew up in and he detested crowded, filthy, noisy cities. So he intended to design a hybrid that combined the best of rural and urban life and left out the worst. Workers would spend part of the year in the factory, part growing crops. It would be, Ford said, a “new Eden.”

Ford also proposed a new system of finance with a currency called “energy dollars.” Economists rolled their eyes but, as always, Ford didn’t care.

Visionary or delusional, Ford came very close to getting the government approval he needed to pursue his Utopia, but the relentless opposition of a lone senator, George W. Norris of Nebraska, put a stop to it. A decade later, when Franklin Roosevelt came to power, Norris would work with the administration to turn Muscle Shoals into the Tennessee Valley Authority — among the first and biggest of the New Deal projects.

And that was just one of Ford’s visions.

Ford always wanted his empire to be an autarky — self-sufficient — and he constantly expanded his operations so his own companies would supply the commodities, goods, and services Ford needed. That was a problem when it came to rubber, a commodity the Ford Motor Company needed in vast quantity. Rubber production was overwhelmingly dominated by the British so Ford couldn’t buy in. His solutions was to make a deal with the Brazilian government to buy 2.5 million acres of jungle where he would create rubber plantations and build a whole new industry. Ford chose poor project leaders, the plantations failed, and the industry never materialized. But the district is called “Fordlandia” to this day.

Now, with that picture of Henry Ford in mind, let’s go back to 1923 and run the counterfactual in which Warren G. Harding does not have the good sense to have a heart attack and die.

As the 1924 election approaches, Harding’s popularity sinks to dismal lows. Henry Ford easily defeats Harding to become the Republican nominee for president. Ford wins the general election and enters the White House in 1925.

The American economy surges that year, unemployment falls. President Ford appears to be every bit the genius his fans thought he was. Blessed with a booming economy, Ford wins re-election in 1928 by the largest margin ever.

In October, 1929, the stock market crashes. The Great Depression sets in. How does President Ford respond?

Not like President Hoover.

President Ford is contemptuous of experts, remember. When they tell him he has to stick to the gold standard, and cut expenditures, and wait for recovery, he doesn’t listen. He trusts his gut. And he does what he has always wanted to do.

He launches the biggest public works programs in American history.

If Muscle Shoals hasn’t already been built, he gets it going, on an even bigger scale than the Tennessee Valley Authority became under FDR — and three years earlier.

Projects like that sprout all over America. With the crisis convincing Americans that government must play a bigger role in the economy and their lives, Ford delivers a far more ambitious, more radical New Deal.

Economists wail. Wall Street is furious. But Ford doesn’t care. The man who thought “energy dollars” were a brilliant idea in 1923 happily embraces all sorts of crazy, debt-fuelled schemes amidst the crisis a decade later (and there are lots of wacky ideas on offer in the early years of the Great Depression).

The short-term result of this anti-intellectual, populist policy-making would be far broader, deeper, and more effective relief for Americans than President Hoover delivered. And much stronger economic stimulus.

So in 1932, the United States is better off than other countries. Americans see that. And they re-elect Ford for a third term.

Ford’s schemes grow in scale and ambition. Huge numbers of Americans are now working for the government, one way or the other, but what matters is that they’re working. The upward trajectory carries on to 1936. And the revered old man — the intrusive, demanding, benevolent father of the nation — is rewarded with an unprecedented fourth term.

German and Japanese aggression begins in earnest. But President Ford is no Franklin Roosevelt.

For most of his life, Ford was an anti-Semite. The statements he made about Jewish financiers manipulating events and starting wars for their own profit were often indistinguishable from Hitler’s. Hitler’s Germany even decorated Ford in 1938, an honour Ford was happy to receive in person. With views often simpatico with Hitler’s, it’s impossible to imagine a President Ford taking a hard line against Nazi Germany unless compelled to by events.

And in his bones, Ford is an isolationist. What concern is it of America’s if Japan attacks China?

The United States does not embargo oil shipments to Japan.

Why should the United States again risk war to stop squabbling in Europe?

There is no Lend-Lease Agreement. Britain receives no assistance from America.

Ford was also a lifelong anti-militarist. He detested spending money on guns and bombs. In these years, contrary to FDR’s policy, President Ford does not expand America’s then-tiny military in preparation for war.

By the election of 1940, Henry Ford is 77 years old. He finally decides to retire.

The next president takes office in March, 1941. It’s possible whoever that is would introduce a more interventionist policy, though it’s hard to see why that would happen under those circumstances. But assume it did. America in March, 1941 would not be on the Allied side in all but name. Its military would not have spent the previous years preparing for war. And most importantly, America would not have embargoed oil to Japan.

That embargo encouraged Japan to consider seizing oil reserves in south-east Asia held by European colonial powers. Japan knew the United States would resist that expansion. So it settled on a a pre-emptive strike on Pearl Harbor to cripple the American ability to intervene.

But with President Ford, there is no embargo. No embargo, no Pearl Harbor. No Pearl Harbor, no war with Japan. And Hitler doesn’t declare war on the United States.

America sits out the war. Nazi Germany wins.

Or so history might have unfolded — if Warren G. Harding had not so exquisitely timed his heart attack and saved the world.

Addendum: You’ll notice I say nothing about probability anywhere. I would argue that at any given moment we face a near-infinite range of possible futures. This necessarily means that any single long-range, grand-scale series of events like I’ve outlined here must be, at most, highly improbable. But I hope I’ve established that, yes, if Warren Harding and Jerry hadn’t exited stage left at precisely the moment they did, the world at least could have followed this pathway to catastrophe.

Thank you, President Harding. And thank you, Jerry.

Also, I should mention a book called “Electric City,” about the Muscle Shoals project and the Tennessee Valley Authority. Chemistry, engineering, and the generation of electricity aren’t exactly enthralling to me but the author, Thomas Hager, did a superb job of making them clear and interesting, and interweaving the politics and visions that drove the Muscle Shoals/Tennessee Valley Authority projects. Well worth your time.