Here’s an experiment you can try right now. All you need is blank paper, a pen, and your memory.

Ready? Write the numbers 1 through 46 on the page. Now list the names of American presidents. You can start at the beginning with #1 and go forward, if you like, or start with the current president and work backwards.

If you can’t remember where a president falls in the order, write his name off to one side. You have five minutes.

(Hint: This guy is #34.)

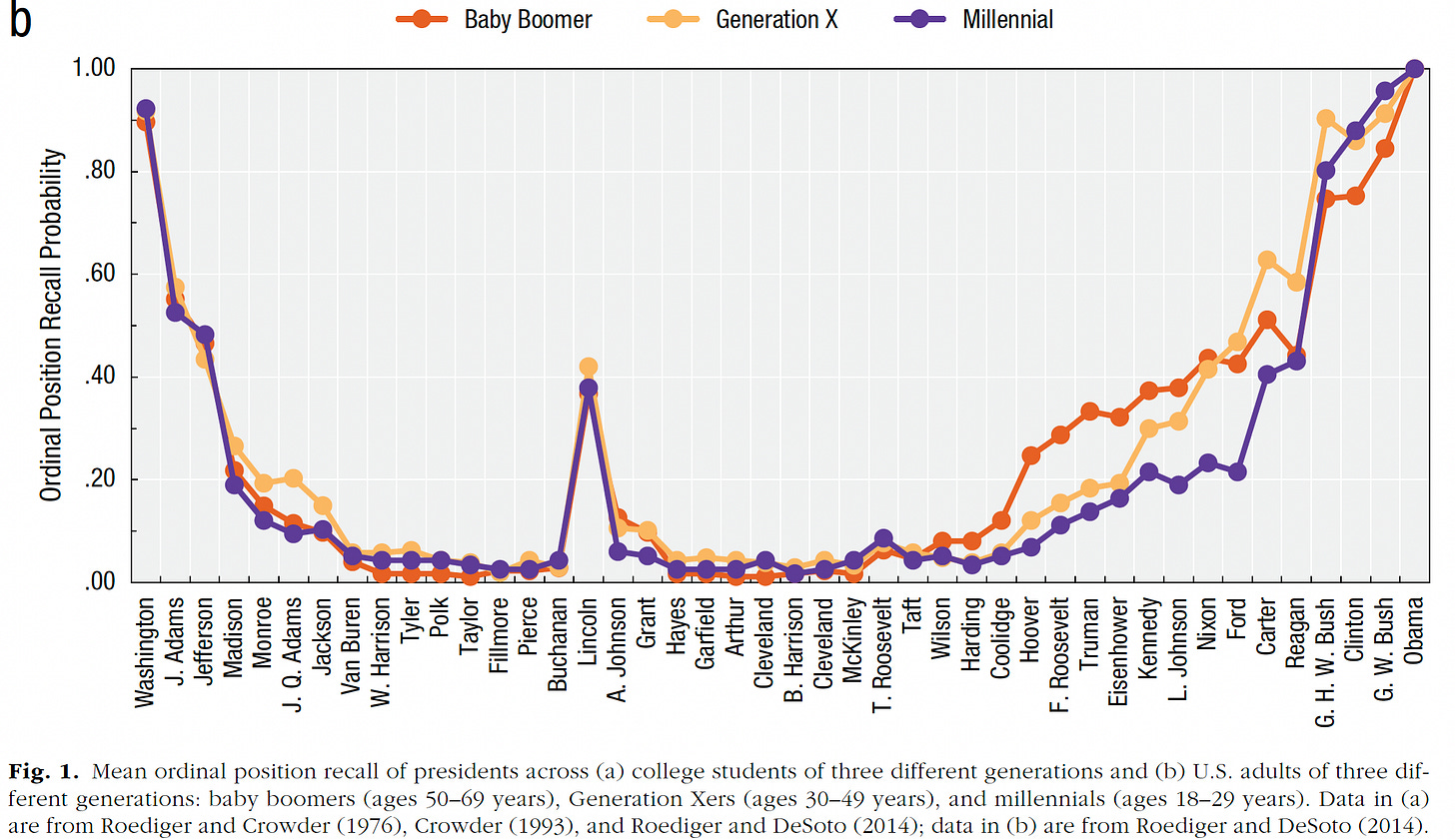

In 1974, the psychologist Henry L. Roediger asked undergraduates to do this exercise. He found that students’ recollections followed a clear pattern: The first several presidents were well known, particularly the very first president, Washington, who was universally remembered. The same was true of the current president and his immediate predecessors. But the further removed recall was from the first and last presidents, the more it declined. Most presidents fell in between the two ends, naturally, and most students could not recall them.

There was one big exception: Abraham Lincoln. His two immediate successors – Andrew Johnson and Ulysses Grant – were also substantially better-remembered.

Put these results on a chart and it resembles a deep, wide crater — with Lincoln sitting on a flagpole in the middle of the crater.

In 1991, Roediger repeated the exercise. The result was almost identical, except the right-hand side of the crater had shifted ahead 15 years.

In 2009, he did it again. And again, the results are basically the same, but shifted ahead. (See charts below, which come from this paper.)

In 2014, Roediger and Andrew DeSoto repeated the exercise with American adults drawn from three different generations – Boomers, Generation X, and Millennials. The same pattern appeared with all three generations, although Boomers and Xers had modestly better recall for presidents who were, for them, in living memory or close to it.

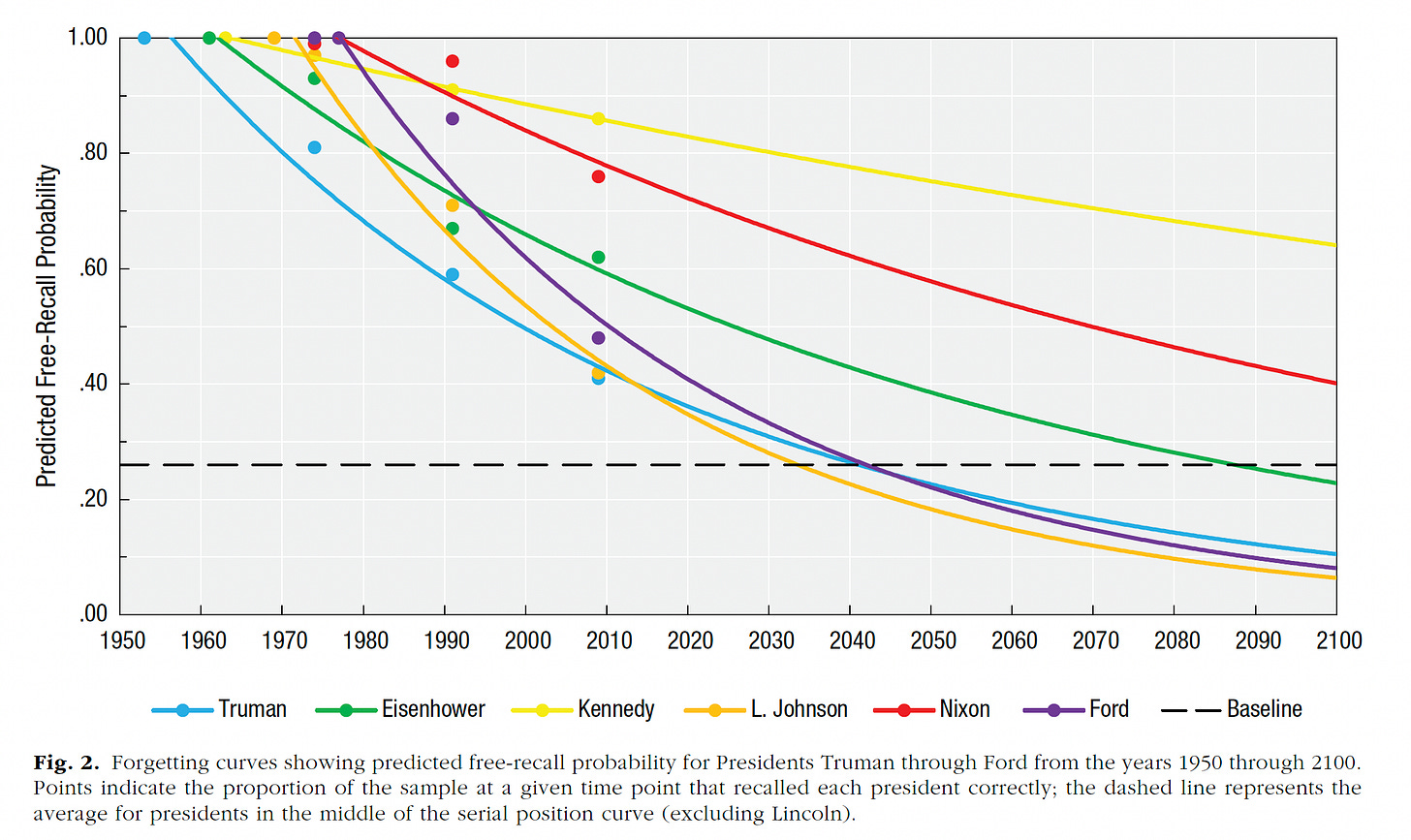

Roediger and DeSoto used this remarkably consistent pattern to predict how presidents will be forgotten in future.

For people who love history and politics (you’re reading this so chances are you’re in that category) this is all very cool in itself. But it has broader significance.

The pattern revealed here fits neatly with lab studies of people’s recall when psychologists give them artificial tasks like “remember this set of words.”

There are what psychologists call “recency effects” – the more recently we encountered something, the easier it is to recall, so items at the end of the list are more memorable. (Donald Trump and Barack Obama? Very recent, easily recalled. Franklin Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover? Much less recent, much harder to recall.)

There are “primacy effects” – meaning the first items encountered are better remembered. (Everybody knows George Washington, and lots know the first few presidents.)

Combine those two and a graph of individual recall on memory tasks typically looks like a crater – high walls on the sides and a big trough in between.

There are also “distinctiveness effects” (also known as “von Restorff effects”) – meaning unusual items are better recalled. (Abraham Lincoln is the president who saved the country in the bloodiest war in American history, then was assassinated. He stands out.)

So what we are seeing is that how Americans recall these important public figures is remarkably similar to how they would recall anything in their personal lives – from grocery lists to the names of friends to who they dated before getting married. And that’s significant.

“Collective memory” is how members of groups – families, teams, corporations, parties, societies, nations – remember their past. Historians, sociologists, and anthropologists have studied it forever. Psychologists only recently got involved but research like this shows that what we know of memory at the individual level may scale up to the collective. And that matters because collective memory shapes how the group sees itself – which influences the group’s perceptions and decisions in the present and its behaviour in the future.

So understanding how memory works at an individual level may be useful for understanding how groups think and act.

It’s also good to know that we will, in time, forget Donald Trump.

Hi everybody: Many people asked if there is similar Canadian research. As far as I know, there is only one small-scale equivalent. I wrote about it, and included a link, here: https://twitter.com/dgardner/status/1506248063928647689

Dan, this is fun but I would like to know how many people in our own country know who were the leaders of the Conservative Party between 1935 and 1957. I am guessing a few will know John Diefenbaker but none will know George Drew.