How to Stop Digging the Hole You're In

Admitting error and changing your mind requires preparation

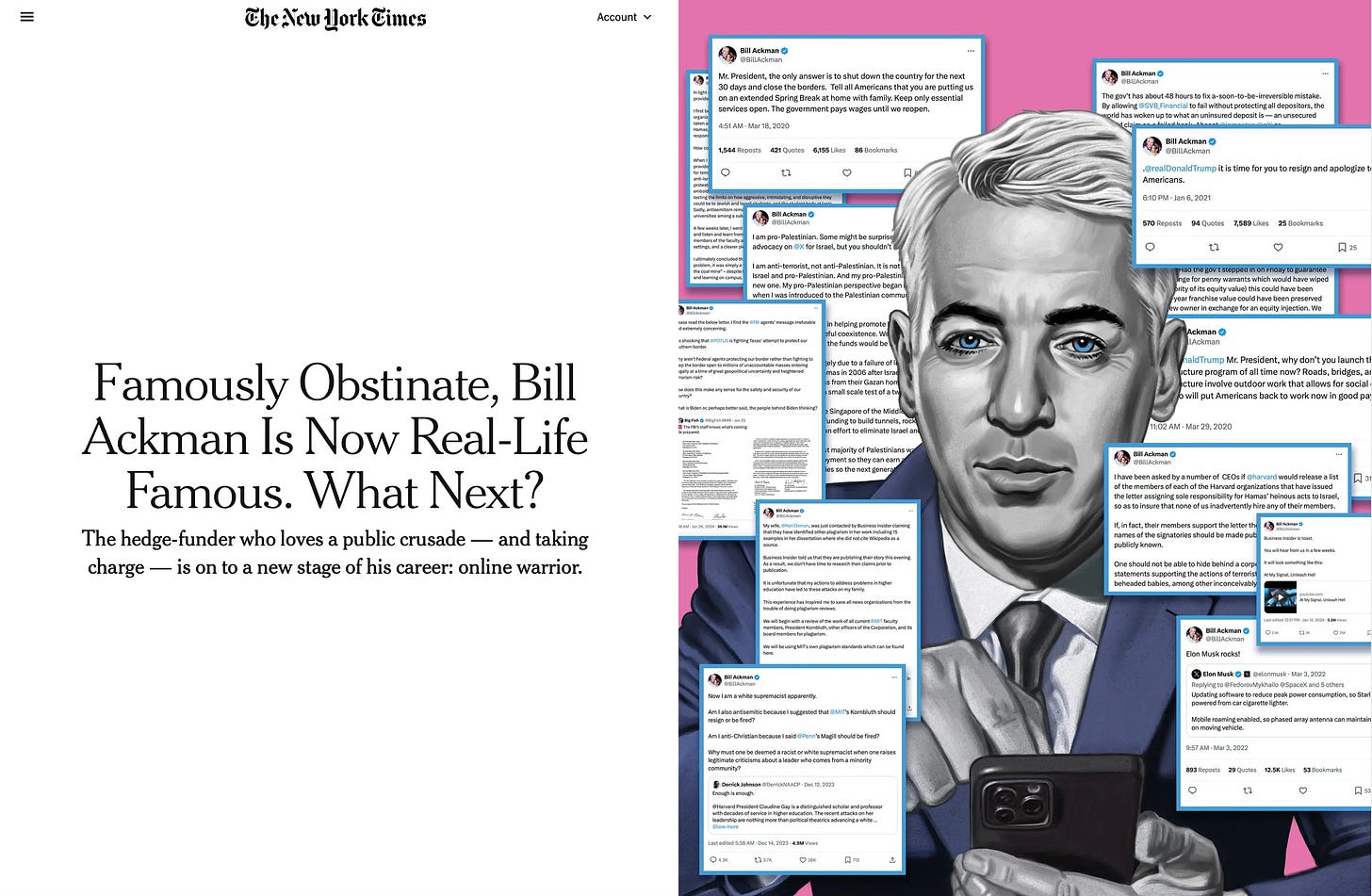

When Harvard President Claudine Gay testified to Congress about her university’s response to anti-Semitism, Bill Ackman was upset. Ackman was far from alone. Lots of people were upset by Gay’s testimony. But unlike lots of people, Bill Ackman is a billionaire with 1.2 million followers on Twitter and a taste for public expostulation. So he went after Gay on Twitter. About Harvard’s response to anti-Semitism, please remember. Bear that detail in mind as I lay out the saga that followed.

With a public spotlight shining intensely on Gay, Chris Rufo (a conservative political activist and leading critic of “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) policies) published what he said was proof that President Gay (a strong supporter of DEI policies in her career as an administrator) had committed plagiarism in her academic work. So Bill Ackman went after Gay on that count, too. And Ackman blasted DEI policies for good measure.

But as many people pointed out, Gay’s alleged plagiarism amounted to repeating snippets of commonplace language used by earlier published sources. There was no evidence she had committed the far more serious thefts — of ideas or artful language — most people think of when they hear “plagiarism.” One who made this point was John McWhorter, a linguist, New York Times columnist, and frequent critic of what we might call the Ibram Kendi/Claudine Gay academic left. “The term ‘plagiarism’ still covers both ‘real’ plagiarism — the theft of another person’s ideas — and the use, perhaps inadvertent, of another person’s language,” McWhorter wrote. That’s unfortunate because the one offence is far more serious than the other. We need a new word for lesser “plagiarism,” McWhorter sensibly concluded.

Neither Rufo nor Ackman seemed interested in such nuances.

But then Business Insider published an article which claimed to find plagiarism in the work of Neri Oxman, a former MIT professor who also happens to be Ackman’s wife. Ackman’s response was dramatic. “In the blink of an eye,” McWhorter noted in his column, “Ackman acquired an exquisite sensitivity to the difference between real plagiarism and the other, accidental-word-copying kind.” Ackman attacked Business Insider for what he deemed shoddy journalism. He called for the reporters on the story to be fired. He threatened to sue and retained a major law firm. And for good measure, he promised to investigate the work of all MIT professors, including the university president, to see if they, too, had committed plagiarism according to the more expansive definition he now rejected.

Then, earlier this week, The New York Times ran a long profile of Ackman whose main theme is how the “famously obstinate” Bill Ackman loves going on the attack and never backing down. You can probably guess what happened next.

Ackman was furious. He attacked The New York Times.

Now that you’re all up to date on this little saga, do you see what happened? Ackman was upset about one thing. He expressed his feelings. Fine. But that wasn’t enough.

He seized every opportunity to repeat and expand the attack. He refused to acknowledge that maybe some of his thinking in these attacks was undercooked, which would have been a relative minor admission of error and required only a modest retreat. He just kept attacking. As a result, a dispute about Harvard’s response to anti-Semitism spread into a multi-front war — a war that has little or nothing to do with Harvard’s response to anti-Semitism.

Admittedly, this is an extreme case. But the dynamic is common. We’ve all seen it. Many of us, like Ackman, have been swept up by it. (Mea most definitely culpa.)

It is summed up in the old joke about what you should do when you dig yourself into a hole: Stop digging.

That is exquisitely simple advice but it is awfully hard to follow because digging in is what people do naturally. Once we have a belief, for any reason, good or bad, we all tend to uncritically accept information that supports the belief while working hard to find a reason to reject information that contradicts it. So the belief gets stronger. That’s garden-variety confirmation bias. It afflicts us even when the beliefs are minor, passing thoughts we aren’t particularly committed to.

But when we speak publicly — when we proclaim our position, pound the table, and loudly insist that I am right, dammit! — our cognitive conservatism grows exponentially. You know the phrase “to eat crow?” Admitting error on something you publicly railed about really is as enjoyable as stuffing the carcass of a scrawny old crow in your mouth. Most people would do just about anything to avoid that. So when life serves you a plate of crow, what do you do? You slap the plate away and tell life to go bleep itself.

In other words — to mix metaphors horribly — you keep digging.

This is why so many arguments on social media start with a person saying something like “popular music is creatively stagnant” and three hours of angry debate later the same person is passionately arguing about infanticide in ancient Sparta. This person’s first thought about infanticide in ancient Sparta may have occurred to him only fifteen minutes ago. He may be Googling like mad to find information to support his case. But he must be right! And that sonofabitch he’s been arguing with for three hours must be wrong! (Again, mea so culpa. But I’m doing better. Kicking Twitter to the curb helped a lot. I strongly recommend it.)

Please note that intelligence and education do not protect against this dynamic. In fact, all else being equal, the intelligent and educated may be at more risk than ignorant dummies because intelligence and education make us more capable of crafting the rationalizations that allow us to dismiss unwelcome information and dig the hole deeper. Bill Ackman is a very clever fellow. That’s part of his problem.

So how can we stop ourselves from becoming the fool trying to dig his way out of a hole?

I have a file in which I keep good examples of people with big profiles and strong views who nonetheless managed to say the hardest words any human being can speak — “I was wrong” — and change their mind. There aren’t many items in it. But the few stories I have all share one thing in common.

To illustrate, I’ll use the most recent addition to my file.

The hero of this story is Glenn Loury, a conservative economist, Brown University professor, and a popular podcaster (often working with John McWhorter) with a large following. For the purposes of the story, it’s also important to know both Loury and McWhorter are black.

This past January, Loury and McWhorter devoted an episode of their show to a new documentary about the death of George Floyd. That film couldn’t be more explosive. In The Fall of Minneapolis, by Liz Collin and J.C. Chaix, the filmmakers argue that Derek Chauvin, the police officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck, was unjustly convicted. Loury and McWhorter discussed the documentary at length and were sympathetic. In another episode, they hosted the documentarians and had them make their case. In part thanks to this promotion, The Fall of Minneapolis has caused something of a sensation on the political right.

But then Radley Balko weighed in with a forensic analysis of the documentary that portrayed it as seriously flawed and misleading.

Glenn Loury responded by doing something astonishing.

He said he was wrong.

And not in a “I was wrong about minor details but basically I’m right” way. And not in a “here are two sentences tucked into the end of a column so get off my back” way. He prominently stated he was wrong, detailed what he was wrong about, and thoughtfully considered why he got it wrong. (Please do not comment on the Chauvin case or the substance of the documentary below. Who is right about that is not the point here. The point is how Loury responded to what he considered compelling evidence he was wrong.)

How often do prominent pundits so frankly admit error about an explosive issue? I can count the number of modern examples that come to mind with my right thumb.

Here’s Loury:

It was not wrong to call attention to the documentary, nor was it wrong to talk to the filmmakers. But I do wish I had not been so eager to accept their conclusions. I’ve spent years decrying the outsized reaction to the death of George Floyd, the riots and the antiractist mania that followed, and the superficial moralism of progressives who claim to find white supremacy at the root of even the most minuscule social infractions. When I saw a documentary that claimed to locate real, empirical corruption at the heart of the George Floyd case itself, I was primed to believe it.

I’ve had to take stock of my reasons for going all-in on The Fall of Minneapolis without subjecting it to scrutiny befitting the magnitude of its claims. Certainly I was ready to accept those claims, but at some level, did I want to accept them as well? I cannot be certain that my desire to strengthen my argument against George Floyd’s canonization did not neutralize the skepticism that should kick in whenever a shocking claim is made, no matter its ideological implications. The documentary’s counter-narrative fit neatly with my own, which should have moved me to seek further verification rather than accepting it at face value.

That degree of frank self-awareness and self-criticism, and willingness to share it publicly, should be table stakes in top-tier punditry. But you’ll find more of it in Donald Trump’s monologues.

Loury went on:

As you’ll see in this week’s clip, John doesn’t think we erred all that egregiously. But I do. I pride myself on remaining open to evidence and reason, even if they disconfirm something I had formerly thought to be true. I think I’ve succeeded in that where Balko’s critique is concerned, but only to the end of correcting an earlier failure. I sometimes describe myself as “heterodox.” That means looking on all orthodoxies with a critical eye, including the personal orthodoxies we develop over time. Without self-reflection and introspection, heterodoxy risks becoming orthodoxy by another name, a shallow rebrand that betrays its own purpose. As John is fond of saying, that won’t do. I may have fallen short this time. But, as I’m fond of saying, God’s not finished with me yet.

That paragraph is so beautiful it makes me want to cry. Every sentence is a gem worth a slow, careful appreciation.

But let me draw your attention to one sentence in particular: “I pride myself on remaining open to evidence and reason, even if they disconfirm something I had formerly thought to be true.”

That’s it. That’s the element that appears in every account I have in which a prominent person gives a full and frank admission of major error.

The best example is John Maynard Keynes.

The legendary economist was, well, let’s be blunt, something of an arrogant prick. Keynes was always the smartest guy in the room. He always had the answer. And if you disagreed, he would be pleased to expose your idiocy with words that cut like razor blades.

But like Glenn Loury, John Maynard Keynes was also proud of being the sort of person who seriously considers new evidence and new arguments, admits error when warranted, and changes his mind. That is what any rational, honest person should do, of course. “But most don’t,” Keynes might sniff. “Unlike John Maynard Bloody Keynes, thank you very much.”

That’s pride. And it makes all the difference.

When we are deeply invested in a belief, admitting error comes at great cost. But the cost isn’t dollars. It’s something more valuable than that. It costs us pride: Any time we loudly stake out a public position, we are implicitly saying to those listening, “I am qualified to make this judgement. I know what I’m talking about.” It’s personal. You are making a claim about who you are and what you are capable of. You say “trust me” to others.

To then admit error is embarrassing, even humiliating. But those feelings are about how you are perceived by others. The worse blow is internal.

To admit error can be a blow to your very self-conception: Maybe I’m not as qualified as a I thought. Maybe my judgement is worse than I believed. Maybe I’m the dummy.

That is why “eating crow” is such a horrible experience. It is deeply, psychologically threatening. It is a blow to your pride. Which is why people will go to extreme lengths — rationalizing like mad, flailing at critics — to avoid admitting error.

But if pride is the cost, pride is also the solution.

Imagine you often say, to yourself and others, “I pride myself on really listening to new arguments and new evidence, on admitting my inevitable mistakes — to err is human, after all — and changing my mind.”

Then one day, you confront evidence suggesting you were dead wrong on a view you loudly and publicly declared. So you admit your error. Publicly and frankly.

How do you feel?

Proud, of course. By publicly admitting your mistakes, you publicly demonstrate that you are indeed the sort of intellectually serious and honest person you claim to be. A blow to your self-conception that could have left you reeling instead becomes confirmation of your self-conception. Your ego isn’t shaken. It is stroked.

For all his self-regard, John Maynard Keynes had no trouble admitting mistakes and changing his mind. And he didn’t do it quietly. He practically boasted about it. Keynes became so notorious for changing his mind that a 1945 Life magazine profile of him called him “the consistently inconsistent Mr. Keynes.” Many people would take that as a slam. Keynes revelled in it. It was proof that he was the sort of man he claimed to be.

Not coincidentally, Keynes’ thinking not only changed, it changed rapidly, and sometimes dramatically. And for the better. We can say this with confidence, without debating Keynesian economic theory, because in addition to being a world-famous economist, Keynes was also an investor. He invested his own money, that of friends and family, and he did some institutional investing. His thinking about investing evolved as rapidly, and sometimes as dramatically, as his thinking about economics, and it got stronger and stronger — the proof being the fortunes his investing made in an era (inter-war Britain) when life was brutal for most investors.

Now look at the sentence of Loury’s that follows the one I highlighted earlier: “I pride myself on remaining open to evidence and reason, even if they disconfirm something I had formerly thought to be true. I think I’ve succeeded in that where Balko’s critique is concerned, but only to the end of correcting an earlier failure.”

Yes, I failed, Loury says. And now, in admitting this failure, I succeeded.

That’s pride talking. And I suspect it’s a big reason why Loury was able to do what most pundits cannot.

Want to protect yourself from trying to dig your way out of a hole? Before you ever pick up a shovel again, tell yourself you are the sort of person who has no trouble admitting error and changing course. Brag about it. You are much more rational than most people! Tell anyone who will listen. Let that fact define you.

That will make it so much easier when the time comes to put down the damned shovel and climb out of the hole.

PS: After writing this post and scheduling it for publication, I learned of the death of the great Daniel Kahneman. This appreciation of Kahneman’s life and work, by Daniel Engber, is a gem, thanks to its focus: Kahneman’s humility and lifelong readiness to say, “I was wrong.”

While finding it difficult to admit error is undoubtedly a part of being human, I suspect that it has become even more difficult in the current climate as norms of what is acceptable have changed. On the one hand, it seems as if statements and actions of politicians which would have demanded retraction, apology or accountability 20 years ago now can be ignored or ridden through without consequence. Sometimes, the breaking of old norms becomes a value to be exalted. On the other hand, the smallest mis-statement or use of an inappropriate word seems to allow for the world to dump on someone incessantly and aggressively. Moreover, while one person may take pride in correcting their past conclusion as facts or their analysis changes, I suspect there is added fear in doing so now as their ‘team’ on that issue will come down on them like a ton of bricks for leaving or betraying the fold.

One of those "synergy" days when it seems as if everything I'm reading is multiple views of the same topic. I just finished finally reading the book version of Burke's "The Day the Universe Changed", where universe-changing depended on *many* proud people admitting previous error, so it was always a long fight for a new truth to be established.

Same day, I read it was 4 years since Anthony Fauci demonization started, and it was much earlier than I remembered, right after he corrected Trump even once on something. Later, he was beat up for changing his mind about masks - admitting they'd been wrong to not recommend them, doing a 180. But the demonization started months earlier. The entire Tony Fauci "controversy" was just beating up expertise itself, fighting against the very notion of a solid truth. NB: Fauci's admission of error was taken as a huge strike AGAINST him by the GOP.

Thing was, my jaw dropped at the 2nd-last paragraph in Burke's book, the big sum-up about the negotiations and fights between science vs myth, which always *compete* to provide humans with a sense of understanding and control. Having noted that we have structures that *try* to open up our prejudices and look at new facts on equal footing with old - academia, journalism - toward a "relativist" approach where no absolute truth is claimed... he suddenly says, in 1985:

"A relativist approach might well use the new electronic data systems to provide a structure unlike any that which has gone before."

And here were are, now arguing what's myth and what's truth in endless online discussions that drive, -and push around- academia, journalism, and politics alike!

Smart boy, that James Burke. Forty years ago.