I love Ken Burns. Even when I don’t know anything about his subject. No, especially when I don’t.

Baseball? Bores me to tears. I have not the slightest interest. But I watched Burns’s long, long documentary about baseball from beginning to end, found it fascinating, and came away with a better appreciation for baseball’s presence and meaning in American culture.

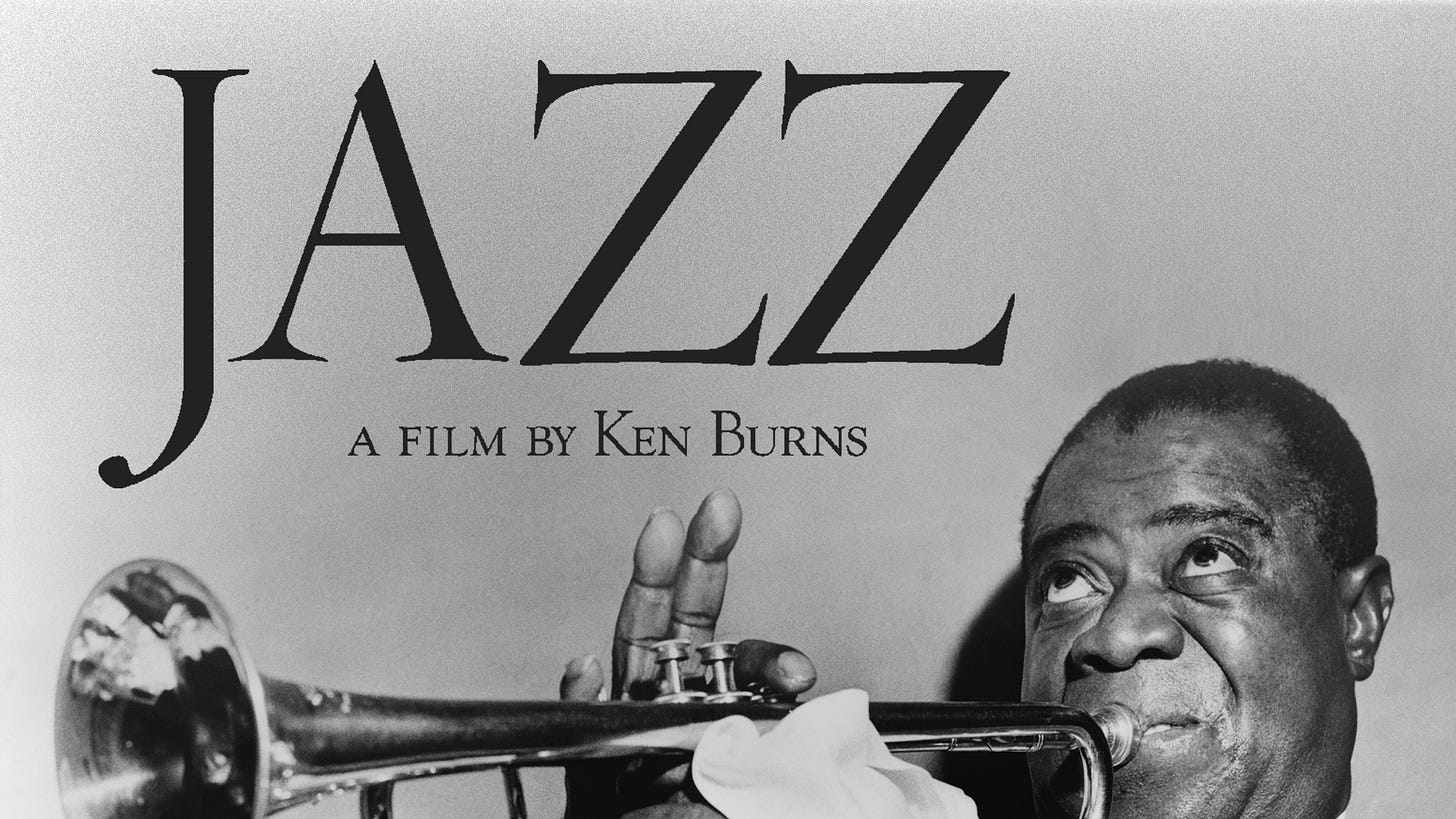

I do listen to jazz but I knew nothing about it until I watched Burns’s documentary. I had no idea Louis Armstrong was such a pioneer. And, as with baseball, I was amazed at what a superb barometer jazz is of many fundamentals of American society, particularly race.

Huey Long. Frank Lloyd Wright. Muhammad Ali. Jack Johnson. The dust bowl. The first crossing of the United States by car. I’ve spent a lot of enriching hours with Ken Burns. (I should note that when I say “Ken Burns,” I mostly mean “the people who make Ken Burns documentaries,” which is more than Ken Burns. In particular, Burns works with his long-time partner Lynn Novick. But “Ken Burns” is now both a person and a brand. Like Thomas Edison.)

Burns has a new documentary on PBS — The United States and the Holocaust. I’ve only seen the first episode but it’s a subject I’m quite familiar with so it hasn’t grabbed me the way some other docs have. But that’s just me.

Today, I want to praise Burns & Co, starting with the smallest of their accomplishments — which is quite substantial nonetheless — and moving to one that’s grand and critical today.

First, technique. How does a documentary filmmaker, who works with motion pictures and sounds to stir thoughts and feelings use the still and the silent — old letters and grainy photographs — to bring history to life? Burns invented new techniques. They were so successful they have been routinely copied, to the point where they are even embedded in standard software programs: When your iPhone automatically assembles your photos into video presentations, it shamelessly copies Ken Burns. Now that his techniques are so common, it’s tempting to treat them as banal and deny Burns credit. Resist that temptation. The ubiquity of what Burns invented is the best proof of his genius.

The United States is also incredibly lucky to have him, particularly given the longevity of his career.

I watched his documentary on Huey Long a year or two ago and I was shocked when it went to old men who explained why the voted for the Kingfish. To have been a voter in the early 1930s, I thought, these men would have to be ancient… Only then did I realize that the documentary is itself old. It first aired in 1985. Only then did I realize how good — how timeless — the documentary is. That was also when another penny dropped: Burns has been doing this work so long that he has done extensive interviews with a huge array of disparate people who are now long dead and gone. His oral history archive must be massive. And it’s there, preserved, to be consulted by future historians. That alone is a considerable accomplishment.

But above and beyond that, I think the United States is lucky to have Ken Burns because of the peculiar era we — the whole developed world — have entered.

The stories nations have long told to define themselves collectively are dissolving. “Today, we no longer have narratives that provide meaning and orientation for our lives,” noted the South-Korean-born German philosopher Byung-Chul Han (a little overstatedly for my taste). “Narratives crumble and decay into information.“ This phenomenon is related to the increasing difficulty we have agreeing on shared facts as the basis for political conversations, and it’s happening in part for the same reasons. The fracturing of 20th-century mass media. The rise of the chaotic kaleidoscope of social media. The empowerment of psychological biases by information technology. Sheer information glut. Disinformation campaigns.

But it’s also happening because the old biases, blind spots, and lies that allowed nations to tell simple, clean, compelling stories about themselves have been peeled back. The marginalized and ignored are being seen. The shameful and the tragic that had been glossed over, or omitted entirely, in the old national stories, are now front and centre.

We can see this shift in academic history, where, over the last forty years, what subject matter qualifies as “history” has changed dramatically. On a podcast recently, the historian of science and technology Ruth Schwartz Cowan — who, in the early 1980s, published a landmark book on the effects of domestic technology with the brilliant title More Work For Mother — discussed how, in the 1970s, older, tenured professors often did not consider women and the home a fit subject of investigation. To them, history was nations, politics, and wars. What Cowan was doing was … something else. The field has changed radically since then and what was peripheral is now central. It should go without saying — but I’ll say it anyway — that this shift was an enormously good thing. History has been vastly enriched by expanding its ambit to include vast swathes of human experience ignored by the generations of mostly white male professors who insisted history was solely about chaps with maps.

We can also see this shift at a more personal level, in the population at large, as sub-national components of identity — race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality — are flourishing and multiplying and becoming the focus of personal definition. Again, that’s often to the good, particularly when it reflects declining marginalization in the public discourse.

But there is, I fear, a cost to be paid. The constant focus on difference and distinction — this is my sub-community’s story, that is your sub-community’s story — generates centrifugal forces tending to pull people apart. The old national stories, however deficient and reprehensible they may have been, were centripetal forces that tended to draw people together. If the balance tips substantially from the centripetal to the centrifugal, how do our societies keep themselves from coming apart at the seams?

Who are we? All of us, together. What knowledge and values do we share in common? What stories sum up who we are? These are fundamental questions of collective identity. If a nation can’t answer them, that nation is on a melting ice floe.

Burns has a PBS-based web portal for exploring his work and American history in general. It is called “Unum,” as in E pluribus unum. I don’t need to belabour the significance of summing up the Burns oeuvre in the word “one.” As he said in a New York Times interview, “It’s important for me to speak to everybody and to be able to try to remind us that we have things in common.”

Burns isn’t merely producing documentaries about whatever catches his fancy. He’s doing something much more ambitious, although that wasn’t his intention when he began.

In a time of profound change and re-evaluation, when old truths are dissolving and identities are fracturing and multiplying, he is offering answers to the question: “Who are we?” And he’s doing it without indulging in nostalgia for past verities, or being wilfully blind to tragedy and shame, or keeping the marginalized out of the spotlight — all the techniques that American reactionaries are using now to defend the old, flawed national narratives they cling to with the desperation of sailors holding on to wreckage.

Ken Burns is writing a national story for the 21st century.

Many criticize this or that aspect of his work. That’s all fair game. But let’s keep this in perspective. In a time of centrifugal forces relentlessly pulling us apart, he is making an inspired attempt to create a centripetal force that draws people together. With informed, evidence-based, thoughtful history, not reactionary politics and myth-making. It’s hard to overstate the value of that work.

As far as I can tell there’s nothing remotely like what Burns has done in other countries.

I’m Canadian. I see the same dissolution of an old national story, the same disintegration, the same proliferation of sub-national identities, the same reactionary impulse to dismiss it all. The need for what Burns does is, arguably, all the greater here.

This past July, during “Canada Day,” Canada’s blandly named national holiday, a national newspaper published a story about indigenous people’s conflicted feelings about the holiday. Most of those quoted denounced Canada’s crimes in the past and expressed little sense of “us.” I can understand the sentiments, but I don’t see how this sort of thinking will do anything but erode national identity, weaken bonds, and cast a shadow over the future of us all. But Chief Robert Joseph got said something much more constructive and hopeful.

Canada Day, from its inception, emphasized colonizers and the colonized country and excluded the time and history that existed before newcomers came and any evidence of our presence in the colonial period. Now, we are weaving together a new narrative that we are all one and should celebrate as one.

The first part of that sentence is, if anything, an understatement. “We think of prehistoric North America as inhabited by the Indians, and have based on this a sort of recognition of ownership on their part,” wrote the beloved teacher, political scientist, and humourist Stephen Leacock in a history of Canada published in 1941. “But this attitude is hardly warranted. The Indians were too few to count. Their use of the resources of the continent was scarcely more than that by crows and wolves, their development of it nothing.” Leacock went on to describe how sparsely populated “the empty continent” was, and concluded “such and no more is the meaning and extent of the Indian ownership of North America,” before writing that North America was awakened “from this long sleep” by the arrival of Columbus. Leacock’s history of Canada actually gave far more attention to the Vikings than all the peoples who inhabited these lands for thousands upon thousands of years.

As to the second part of Chief Joseph’s statement — “we are weaving together a new narrative that we are all one” — that is precisely what needs to be done. Answer the question: Who are we? All of us. Together.

That’s a huge undertaking. We desperately need a Ken Burns. Or two or three.

I’m not a close enough observer of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, much less continental Europe, to know if this applies to the same degree there. I suspect so in the latter two. Maybe less so in the UK, where popular history remains a thriving industry. (Please share your thoughts below if you have a personal or professional perspective.)

But I do think the decline of the centripetal and the rise of the centrifugal is happening all across the developed world, to one degree or another, not least in the United States.

We all need to look at what Ken Burns is doing.

Can you imaging a Burns-like documentary of residential schools? What a blessing that would be.

The opposite of Pierre Berton, for whom nothing mattered but drunken, genocidal Scots and railways. Leacock's statement is an accurate reflection of the settler-descended chauvinism of the time, and in his defense, there was little evidence to suggest otherwise.

With modern archaeology and anthropology, we safely assume that there was social and political friction and tumult, up to and including war, for thousands of years before First Contact. Our ancestors didn't have Enlightenment when they first arrived. They were party crashers who had no idea that they were ruining it for everybody. If we'd been smarter, we would all be Métis now.