Is The AI Backlash The Same Old Story?

A close look at Marc Andreessen's claim

Elsewhere on Substack, Marc Andreessen recently published a fierce defence of artificial intelligence.

I’m not endorsing the content of Andreesen’s essay. In fact, this post will mostly be a criticism of a particular point he makes. But I do think his essay is well worth your time for a couple of reasons.

There’s been a scarcity of strongly pro-AI voices in the debate, particularly now that the tech giants have made the political calculation that it’s better to rush ahead and lead the parade to regulation than to be trampled under it. I support regulation. But I also know that one-sided debates are a bad way to understand reality and a worse way to make regulations. Andreessen has done us a service, even if you think he’s quite wrong.

More specifically, the good that AI could do has received a fraction of the airtime given to the potential harms. That’s understandable. Even defensible, up to a point. But it helps to have a fuller, richer, more imaginative picture of what AI could do for us alongside what it could do to us.

You should also read the essay because Marc Andreessen is Marc Andreessen, co-creator of Mosaic and Netscape, and co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz, an influential Silicon Valley venture capital fund. He’s a central node in Silicon Valley’s brain. If you want insight into what a big chunk of Silicon Valley is thinking, reading Andreessen is a good way to start.

But in this post, I’m going to set all that aside.

Instead, I’m going to zero in on one small section of the essay. It’s a little tangential to the piece. It may seem minor, even trivial. But I don’t think it is. In fact, I think it has important implications that warrant careful scrutiny.

This is the section in Andreessen’s essay:

In contrast to this positive view, the public conversation about AI is presently shot through with hysterical fear and paranoia.

We hear claims that AI will variously kill us all, ruin our society, take all our jobs, cause crippling inequality, and enable bad people to do awful things.

What explains this divergence in potential outcomes from near utopia to horrifying dystopia?

Historically, every new technology that matters, from electric lighting to automobiles to radio to the Internet, has sparked a moral panic – a social contagion that convinces people the new technology is going to destroy the world, or society, or both. The fine folks at Pessimists Archive have documented these technology-driven moral panics over the decades; their history makes the pattern vividly clear. It turns out this present panic is not even the first for AI.

That last paragraph is the sticking point.

Andreesen is saying, in my paraphrase, “every time we introduce a major new technology, society loses its collective mind in ways that look embarrassing later. The reaction to AI is just the latest iteration of this old story. Get a grip, people.”

That is arrogant and dismissive.

Worse: It is wrong.

I’ve spent the past few years researching popular reactions to the introduction of technologies that we now consider old and commonplace. I’ve read what historians have written. I’ve immersed myself in the magazines and newspapers of the day.

And I don’t recognize Andreessen’s description of the past.

It’s true, of course, that every new technology has raised concerns and criticisms, some of which seem unfounded to posterity. But are these all “moral panics”? Some people slap that label on almost any concern they think isn’t, or wasn’t, reasonable, but that’s not what the term originally meant, nor how it should be used if it’s to be meaningful. A true moral panic is a mass phenomenon in which something is widely seen as a threat to social values. An example is the 1980s-era belief in secret Satanic ritual abuse of children and repressed memories of victims. Widespread. Mainstream. Consequential. That was a moral panic.

Were there moral panics in response to the introduction of major new technologies in the past? I can think of a couple of instances which could, I suppose, possibly qualify. If we keep the bar low. But they were pretty minor and inconsequential. More importantly, they were not remotely on the scale of what we are seeing now in response to AI.

Yet Andreessen says what’s happening now is no different. Freakouts about important technologies always happen, he claims. It’s a universal law.

Why does he think that?

He thanks “the fine folks at Pessimists Archive” for having “documented these technology-driven moral panics.” Their work “makes the pattern vividly clear.”

That does make something vividly clear. But it’s not what Andreessen thinks.

For those who don’t know, Pessimists Archive is a Twitter account, website, newsletter, and (formerly) a podcast whose stated goal is “to jog our collective memories about the hysteria, technophobia and moral panic that often greets new technologies, ideas and trends.”

To this end, Pessimists Archive scours old newspapers and magazines for stories fears that sound ridiculous to us today.

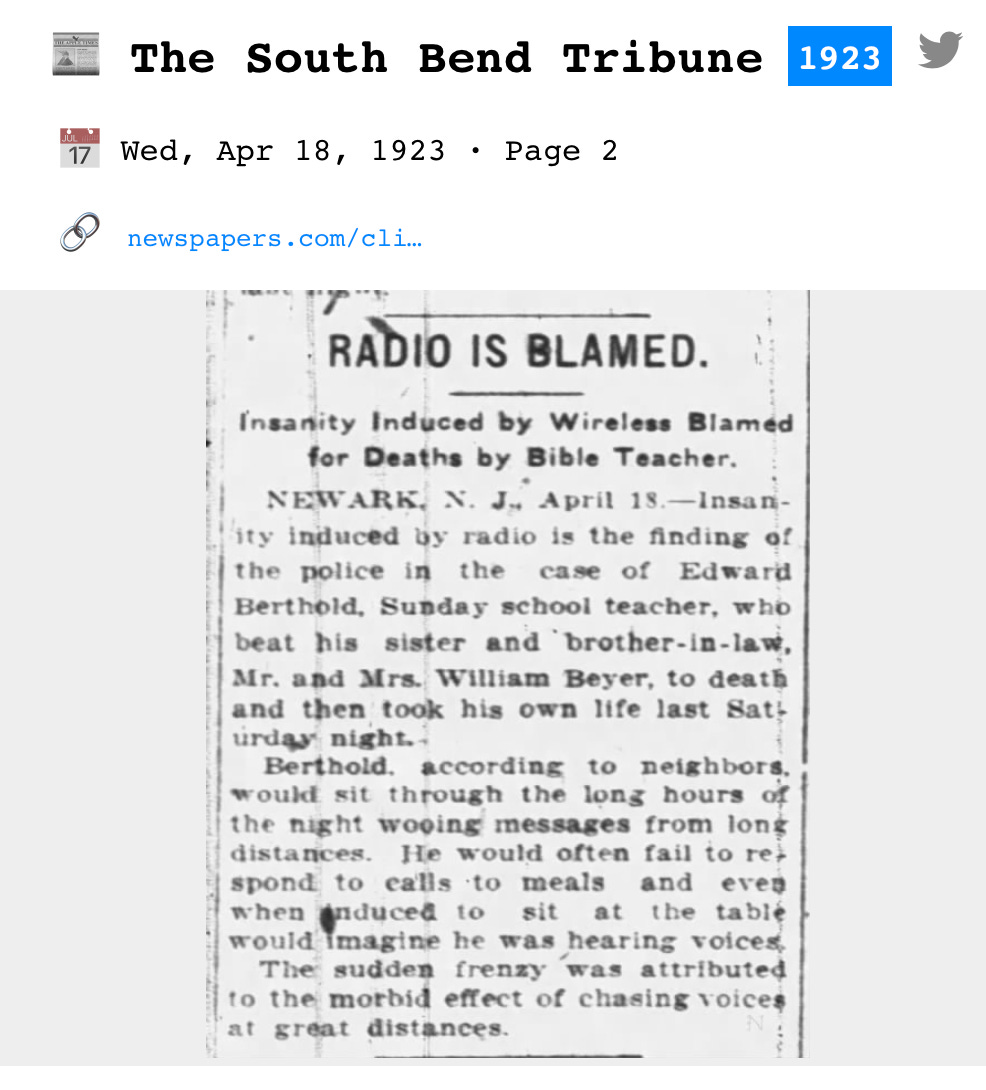

Here’s a typical example:

And another:

As readers of PastPresentFuture know, I love reading old newspapers and magazines, and I especially adore oddball little stories like these. For quite some time, I listened to the Pessimists Archive podcast and followed the Twitter account and I enjoyed it and guffawed as much as anybody.

But then I started studying old technologies seriously and reading what scrupulous historians had written about the social reception of these old technologies.

And I started combing through old publications expecting to find scads of stories like those Pessimist Archives collects and promotes. After all, they have so many of them. The impression I got is that newspapers and magazines back in the day were stuffed with them.

It made sense that they would be. Newspapers and magazines — in the past as today — are biased toward stories involving novelty and negativity for the simple reason that human psychology is biased toward novelty and negativity. These attributes grab our attention and make information more memorable. So if an editor hears about allegations that a sexy new technology like radio or cars may be harmful or dangerous, well, that’s a damned good story. Whatever its source. Whatever evidence supports it. Any editor worth his or her salt would want to immediately play up that story for all it is worth — particularly in, say, the New York City of the 1920s, where newspapers were in a war for readers and the new tabloids were dragging the low professional standards of “yellow journalism” even lower.

Which is why I was surprised when I found that these sorts of stories were much rarer than I expected.

They weren’t rare in terms of sheer numbers, of course. If you spend a lot of time looking for them, you will indeed find them by the dozens and scores — as Pessimists Archive has demonstrated. And when they are all collected together, you will have a lot of stories — stories that give the impression that people in the past lost their heads over these technologies. Every time. Just as Marc Andreessen said.

But the absolute number of such stories doesn’t actually tell us much about what people were thinking. What matters far more is the relative number of such negative stories.

Think of it this way: Radio broadcasting only really began in 1920 but its growth was explosive, with audiences growing from the hundreds to the millions by 1925. Radio was a phenomenon — at least as big as the Internet in the late 1990s.

Newspapers and magazines were all over it, naturally. I don’t know the total number of stories that were published over the first decade or two of radio but it was undoubtedly massive. Some of those stories merely mentioned or discussed radio, without offering positive or negative views about it. Other stories were positive. Still others were negative.

It’s only in the last group that we may find stories that could possibly support the conclusion that there was a moral panic.

If we are to judge whether there really was a moral panic, we need to see the number of negative stories relative to the number of stories about radio that were positive or neutral. If we don’t — if we simply ignore the positive and neutral stories — we could develop an extremely skewed perception.

To illustrate, consider these (made-up) numbers.

Imagine the total number of stories about radio is 50,000. Let’s say 30,000 of those stories merely mention the technology. They’re neutral, expressing neither positive nor negative views. Another 19,900 are overwhelmingly positive, filled with hope and excitement for this wonderful new thing.

A final 100 are very negative. They raise baseless fears. They make nutty claims. Tinfoil hat stuff. The stuff that would definitely support a “moral panic” narrative.

Knowing these facts, what could we say about how people thought and talked about radio in those years?

Clearly, the overall picture is not one of moral panic. Quite the opposite. At most, a tiny minority was alarmed. That’s it.

But now imagine that some people combed through the archives. They ignored the 30,000 neutral stories. They ignored the 19,900 positive stories. But they carefully collected each and every one of those 100 negative stories.

Then they highlighted those stories, one by one, portraying them in the most negative light possible. And they claimed as historical fact that there had been a moral panic. As these stories prove.

If this presentation of the evidence were all you knew about the subject, what would you conclude? Of course there had been a moral panic! Look at all those stories! The evidence is overwhelming.

Thus, reality is turned on its head.

In my judgement, that is what Pessimists Archive has done and continues to do. And influential technology thinkers like Marc Andreessen have been misled as a result.

There’s some irony here. The sociologist who coined the term “moral panic,” Stanley Cohen, wrote that in a moral panic “the untypical is made typical.”

No one is doing more to make the untypical appear typical than “the fine folks at Pessimists Archive.”

Lots of smart people I know love Pessimists Archive. I know this because they have recommended it to me over the years. Like Marc Andreessen, they think it’s good history.

So it pains me a little to say this, but, no, my friends, you’re wrong. What Pessimists Archive does is not historical research.

Pessimists Archive started with a firm conclusion in mind. The people behind it root through archives looking for anything that confirms that conclusion while ignoring anything that doesn’t. And they present what they find with the goal of convincing people that their conclusion is true.

In public policy circles — where “evidence-based decision making” is the gold standard — this sort of analysis is sometimes called “decision-based evidence making.”

But what I think the more accurate label for what Pessimists Archive is doing is “propaganda.”

I mean that word in its precise sense, not as an empty pejorative. “Propaganda” has the same roots as “propagate.” It simply means to promote and spread. Pessimists Archive is not doing historical research. It is using history to promote and spread its belief.

That’s clear even in this article, which quotes one of the original people behind Pessimists Archive. And please note that the source of that article is the Charles Koch Foundation.

Yes, that Charles Koch — ultra-conservative, head of an industrial empire, and one of the richest men in the world. The Charles Koch Foundation helped fund Pessimists Archive, as it has funded other one-sided, ideologically driven projects — notably at the Cato Institute, a Washington DC think tank — whose goal is to push back fears about technology.

Normally, I wouldn’t mention funding like this, as I feel that angle is too often used as a cheap way of dismissing contrary points of view. But in his essay, Marc Andreessen argues many AI critics are, in effect, funded to be critical, and he thinks this diminishes their credibility. That’s his prerogative. But if he thinks that way, he’s got some Bayesian updating to do.

And while he’s at it, I would invite him to consider the following thought experiment.

Imagine that I loathe Silicon Valley, for whatever reason.

So I fire up the Google-box and go looking for dirt. Stupid statements. Nonsense. Outrages. Indictments. Prison sentences. Anything that makes Silicon Valley types look greedy, vicious, arrogant, foolish, or dangerous.

I stick with facts, please note. I’m a careful researcher and I consider myself ethical. I will not promote lies.

But in doing my research, I ignore literally anything that does not support my conclusion that Silicon Valley is loathsome. Stories of generosity, perceptiveness, or wisdom? Ignore them. The good done by Silicon Valley? Ignore it.

And when it comes to the factual nuggets I collect, I omit any details that could make them appear a little more complicated, a little more nuanced — a little less condemnatory.

I do my research, in other words, not like a scientist who wants to learn the truth. I do it like a lawyer determined to win.

It won’t take long for my file to grow thick. After all, there’s plenty of dirt in Silicon Valley. As there is in any large, wealthy, important industry. (See that last bit? That’s exactly the sort of exculpatory detail I won’t ever mention.)

Now I get a Twitter account. Every day, I take an item or two from my thick file and tweet it, always taking care to write and present the tweets to make the story look as bad/silly/outrageous as possible.

I produce podcasts in which I laugh and sneer at my targets, and invite the audience to join in the mockery.

Will I develop a following? Certainly. Lots of people have a deeply rooted ideological hostility toward much of what Silicon Valley represents. For them, my Twitter account and my podcasts will be pure confirmation bias — and will feel as good as easing into a warm bath. They’ll tell their like-minded friends. Who will tell their like-minded friends. I’ll have 50,000 followers in a month or two. Maybe more. Hell, if I had started doing this when Elon Musk bought Twitter, I’d already be at a quarter-million followers by now.

Then things will really start to cook. My most energetic followers will dig up new leads and send them to me. Disgruntled employees in Silicon Valley will DM me dirt. People will start to donate money, allowing me to devote more time to this project, or hire assistants. I might even find a simpatico billionaire who wants me to really scale up.

Another dynamic will also work in my favour. As people listen to my daily barrage of stories, their anti-Silicon Valley views will intensify. How could they not when, every day, they learn of more evidence that Silicon Valley is awful? Ambivalence becomes dislike. Dislike becomes loathing. Loathing becomes hatred. As feelings intensify, people’s support of my work — from promotion to donation — will also heat up.

I’ve created a positive feedback loop: More content generates more followers, passion, and support. Which generates more content. Which generates ….

Would Marc Andreessen and other Silicon Valley types think this is all incredibly unfair? Would they think that, even though I only ever share factual stories, I am promoting a grossly distorted image of reality?

I’m sure they would. And they’d be right.

Yet there is little difference between what I did in this thought experiment and what Pessimists Archive really does.

And if you think the dynamics of my thought experiment are outlandish, bear in mind that they are based on nothing more than basic social psychology. Confirmation bias. Group polarization. Information cascades (also known as “availability cascades.”) Combine them into a feedback loop and ever-larger numbers of educated, intelligent people may eventually hold beliefs that are wildly at odds with what a rigorous review of the evidence would show.

I’m sure Marc Andreessen knows and understands these mechanisms. In fact, he wrote a short essay about information cascades. But as the legendary Daniel Kahneman has always insisted — even pointing to himself to illustrate — merely being aware of psychological traps is not enough to prevent yourself getting caught in them.

This is about much more than history, of course. This really matters here and now.

Contra Andreessen, the negative reaction to AI we are seeing is not yet another example of a phenomenon we have seen every time a major technology is introduced. It is so much bigger. And so much more intense.

That’s not to say it’s right! But it is different.

Another way the present situation differs, I would suggest, is the relatively muted level of hope and excitement we are hearing. There is some, of course. But nothing like what greeted electricity, radio, and the rest.

Surely, this should be cause for reflection from the tech sector.

Why is there so much fear and hostility? Why isn’t there more excitement about what could be a truly spectacular new technology? Why isn’t tech trusted? What are the wider social contexts?

But because Andreessen has convinced himself — with the help of the ahistorical propaganda of Pessimists Archive — that big new technologies always generate major public freakouts, he isn’t reflective. He is dismissive: Yet again, you people are losing your shit. You really should learn some history and get a grip.

He is like the man who comes across a distraught person and thinks the best response is not to learn more about why the person is distraught. It’s to say, “you always get hysterical! Calm down!”

For the record, I am not criticizing Pessimists Archive or Marc Andreessen because I am ideologically opposed to either. On the contrary. I’ve been writing about how progress is real — that we are blessed to live in the present because technology has improved human existence immeasurably — for the better part of two decades. See my first book. That is a central theme.

I think technophobia is real and destructive. I’ve written lots about it.

And Silicon Valley? I remember the first time I sat down to lunch at a VC’s conference and chatted with a random assortment of engineers and dreamers. They were amazing. They burned with the belief that, yes, we can make life better. And they had practical plans to make it happen. I loved it. I felt like I was seeing humanity at its best.

But as the wise have always understood, we are all flawed creatures, no matter how brilliant we may be. Confidence can curdle into hubris. An informed perspective can be simplistic if it excludes others. Facts poorly gathered and ill-considered can distort reality.

Even the best and the brightest may embrace bullshit if they let their vigilance slip.

Let us also recall that the phrase “the best and the brightest” comes from the title of David Halberstam’s book about the origins of the Vietnam War — when brilliant people deluded themselves and created a catastrophe.

That’s a real lesson from history.

There's a proposition in metaphysics (epistemology?) that, "If it's conceivable, it's necessary." As far as I'm aware, the logic supporting that is unassailable - though it has been over 50 years since I studied philosophy so it may be that the proposition has since been disproved.

In any event, the issue remains, in my view, that of machine learning, and the possible outcomes that can arise from that. Artificial intelligences are learning from one another, and are doing so in a language unknown (and untranslatable) to humans. They are a fundamental component of the internet of things, which is far more than "intelligent" refrigerators and thermostats.

What is "good" or "bad" is a human construct - they are the values of a society at any particular time. Does it even make sense to consider whether AI is capable of incorporating human values (which are dynamic and not universal)?

Within that context, the next issue that causes me considerable unease is the idea that humans can somehow regulate, presumably through legislation, what AI can and cannot do. the interconnectedness of AI is already global, but there are literally hundreds of legislative jurisdictions, and while the UN can adopt Conventions, it cannot enforce anything. And in any event, even if some sort of AI Convention could be adopted, how could it possibly be enforced?

Hence my apprehension. If the worst comes to pass will I still be around to experience it? Probably not - but my kids and their kids probably will. I don't like that thought.

As an afterthought, not that I've ever used it, but I wonder what kind of essay ChatGPT would come up with on this subject.

Andreessen and the Pessimists' Archive might overstate the "widespread moral panic" angle for the reasons you state. However, the more relevant point is not how widespread Luddism/techno-fear was for previous emerging technologies, but whether it was correct. Has it ever been?

If AI fear is more widespread now than, say, radio fear was in the past, that doesn't prove anything except perhaps that in the West of today, people seem to be more fearful about *everything*, despite living longer more prosperous lives than ever before.