Is this the End of an Era? Or even a Watershed of History?

Maybe. Maybe not. It is literally impossible to know -- and anyone who says otherwise is deluded or selling you something.

“Donald Trump’s return to power is proof that we have lived through a real turning point in history, an irrevocable shift from one era to the next.” Thus spake Ross Douthat in The New York Times.

Pundits are forever declaring the coming and going of eras. Most such grand pronouncements are soon forgotten. That’s fortunate for the pundit. Because they are mostly wrong.

There’s a reason for that. Now is an excellent time to come to grips with that reason — and its implications for how we should think about the present and the future.

Want to see a genuine, indisputable turning point in history?

In March, 1933, Franklin Roosevelt became president and immediately launched a barrage of unprecedented laws, programs, and agencies known to history as the New Deal. It changed America in critical ways. Those changes became part of the foundation of the United States. Many still exist, shaping America in the 21st century. If anything was “an irrevocable shift from one era to the next,” surely the New Deal qualifies.

But imagine this is 1934. Or 1935. Or maybe it’s 1937, when Roosevelt was sworn into office a second time. Could you have known that you were living in watershed years? You could certainly feel that you were. Lots of people did. And said so. But notice the word “irrevocable.”

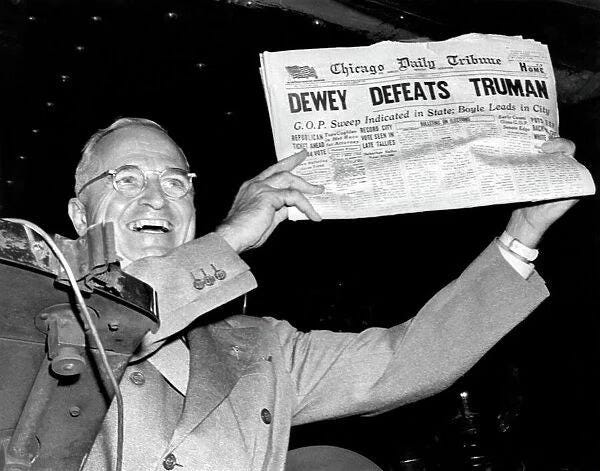

In 1934, the New Deal was still very much revocable and the Republicans intended to revoke it at their first opportunity. But they lost the White House in 1936. And 1940. And 1944. So the New Deal was safe in those years. And in 1948, Roosevelt’s vice president, Harry Truman, won the White House, saving the New Deal for another four years. Still, the Republicans wanted to scrap it. In 1953, the Republicans finally took the White House. But the new Republican president, Dwight Eisenhower, decided scrapping the New Deal would be a brutal, possibly crippling fight, so he told Republicans to let sleeping dogs lie and the GOP made its peace with the New Deal. Then, and only then, was the New Deal made a secure and unquestioned part of American life.

So in the 1930s, the only way to really know that the New Deal marked a true watershed in American history was to accurately foresee how electoral politics would evolve 15, 20, or 25 years into the future. And that was impossible.

Want proof that it was impossible? Consider that Truman was overwhelmingly expected to lose in 1948 but he eked out a victory. It was one of the biggest upsets in American history. If it hadn’t happened, history would have changed spectacularly — including a return to isolationism and the scrapping of the New Deal. And Dwight Eisenhower? He didn’t want to get into politics. But in the lead-up to the 1952 election, which the Republicans were again expected to win, the leading candidate was an old-school isolationist who very much wanted to take America back to the 1920s. Eisenhower thought that would be a disaster so he ran for the Republican nomination and won. If Eisenhower had decided instead to enjoy his celebrity and new wealth — selling his memoir war netted him roughly $11 million in today’s money — the US likely would have gone back to isolationism and scrapped the New Deal.

So to know in the 1930s that the New Deal was a watershed, you had to correctly forecast a long series of events far into the future, including events so surprising they stunned informed observers when they happened. That’s impossible. Hence, in the 1930s, it wouldn’t have been possible to truly know the New Deal was a watershed.

Here’s another illustration, just to show this isn’t an American thing.

To this day, France celebrates the beginning of the French Revolution with Bastille Day on July 14. But if you had been a Frenchman living in those years, and if you had seen the storming of the Bastille, would you have known this event was one of the world’s great watersheds? Not in the least. There was lots of unrest across France in the months and years before then. Indeed, many historians point to other events as the “true” kickoff of the revolution. To someone living in Paris at the time, the storming of the Bastille was a small, ugly little affair easily forgotten in the long flurry of events before and after.

So why is the storming of the Bastille seen as one of history’s great watersheds? Not because of the event itself.

What turned a minor bit of civil unrest into a historic watershed was two things: First, it was all the events that followed, which, together, really did amount to an historic watershed. Second, when people looked back on their transformed world, they rather arbitrarily chose the storming of the Bastille as the single event they would use to mark the beginning of all that change, and thus a symbol of all that change. When they did that, they could easily have settled on any one of half a dozen or more such events. But that event won the lottery.

That’s contingency piled on contingency piled on contingency. History could have gone in innumerable different directions — and if it had, only specialized historians would know anything about the storming of the Bastille today.

So, if you were sitting in a Paris cafe a month after the storming of the Bastille, could you have thought, “this is the end of an era?” Maybe. If you were grandiose. But that wouldn’t have been a thoughtful analysis. It would have been little more than vague speculation.

Which is what most punditry proclaiming the coming and going of eras amounts to.

Maybe Donald Trump’s victory will mark the end of an era. Maybe it will even amount to a great historic watershed. Or maybe it will come to be seen as a brief period of turmoil before America settles down and returns to the course it was on.

Think that last option is impossible? Douthat does.

But consider: Between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the Great War, as its economy and international trade grew massively, the United States steadily shed its traditional isolationism and increasingly got involved in international affairs. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany and an immense new American army sailed for Europe. Enthusiasm for the war was overwhelming. America was going to make the world safe for democracy. Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” would reshape the globe. And as the war ended in victory, Wilson prepared to take America’s place at the head of the table in peace negotiations — and in creating Wilson’s “League of Nations,” within which America would lead.

Talk about a watershed moment. A new era! There’s no going back!

But Wilson was politically inept. He fell ill and was effectively disabled and sidelined. The United States suffered a severe recession. With the American public hurting and increasingly disillusioned, Republican presidential candidate Warren Harding promised “a return to normalcy” in the presidential election of 1920 — and that meant, among other things, scrapping all this involvement with international tomfoolery. Harding won. So then, after the no-going-back events of the Great War and America’s acceptance of the mantle of leadership … the United States took off the mantle of leadership and went back to isolationism.

There are countless more moments in American history which seemed to be historic watersheds — obviously! — which fizzled in unexpected ways. My favourite: When George W. Bush was re-elected in 2004, winning the popular vote and taking control of both the Senate and the House of Representatives, Bush’s political Svengali, Karl Rove, compared the moment to the McKinley era — Rove knows history — and declared it was the beginning of Republican dominance that would last a generation. It lasted two years. A converse example also involves Bush Jr.: The presidential election of 2000 was widely regarded as a low-stakes snoozer that only became interesting thanks to the “hanging chads” in Florida. (Ask your parents, kids.) It was the “meh” election. And through the first months of Bush’s administration, “meh” was the running theme. But then came 9/11. Although those responsible had no connection to Iraq, Bush and his brain trust decided to carry out the invasion of Iraq they had long desired, producing a fiasco so vast it increasingly looks in hindsight to be one of those rare watershed moments in history — an invasion that probably wouldn’t have happened if the it-doesn’t-matter election had gone the other way.

A little humility is in order. In fact, a lot of humility is an excellent idea when it comes to assessing the importance of current events: The meaning and importance of events depends entirely on the events that follow, and to the extent those later events are unpredictable, so the meaning of the earlier events is as well. And when you’re looking at timeframes of five, ten, twenty years and more, and you are trying to forecast politics, you are truly in the land of the unpredictable.

Speculation is fine. It’s always good to entertain hypotheses. But we have to be careful that in doing so we don’t fool ourselves into thinking we know more than we do. Possibilities aren’t probabilities, let alone certainties. Don’t think you or anyone else can spot watershed moments in history as they are happening — at least not any better than a flipped coin.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is why I will never be a famous New York Times columnist.

Thank you. While we often grasp for seeming-certainty to avoid the anxiety of the unknown, in this case undetermined-ness is the great comfort.

It seems to me that from some paths you go down in this essay, it could also be argued that a watershed moment literally is not a watershed moment at the time; the end of an era is literally not the end of an era until later events make it so. So it’s not just that you can’t know, it’s that it can’t BE, until the future arrives.