Regular readers know how I feel about Donald Trump. His election was horrible. His re-election is a disaster.

But I won’t go on about that.

Here, I simply want to lay out two thoughts that draw on history.

The first casts this moment in a darker light than you may have considered. But the second offers at least some modest hope.

In any event, we must “keep buggering on,” as Winston Churchill often put it. Churchill’s life was a rollercoaster of highs and lows, sometimes with the fate of the world riding on which way the rollercoaster went next, and he got through all that while coping with depression. “Keep buggering on” was his way of expressing the attitude that saved him. He often urged others to do the same. (Although he would say “keep bumbling on” if ladies were present.)

Churchill even made it an acronym: KBO.

Keep buggering on. Sound advice, now and forever.

KBO, everyone.

KBO.

#1/ The Great Depression: Compare and contrast

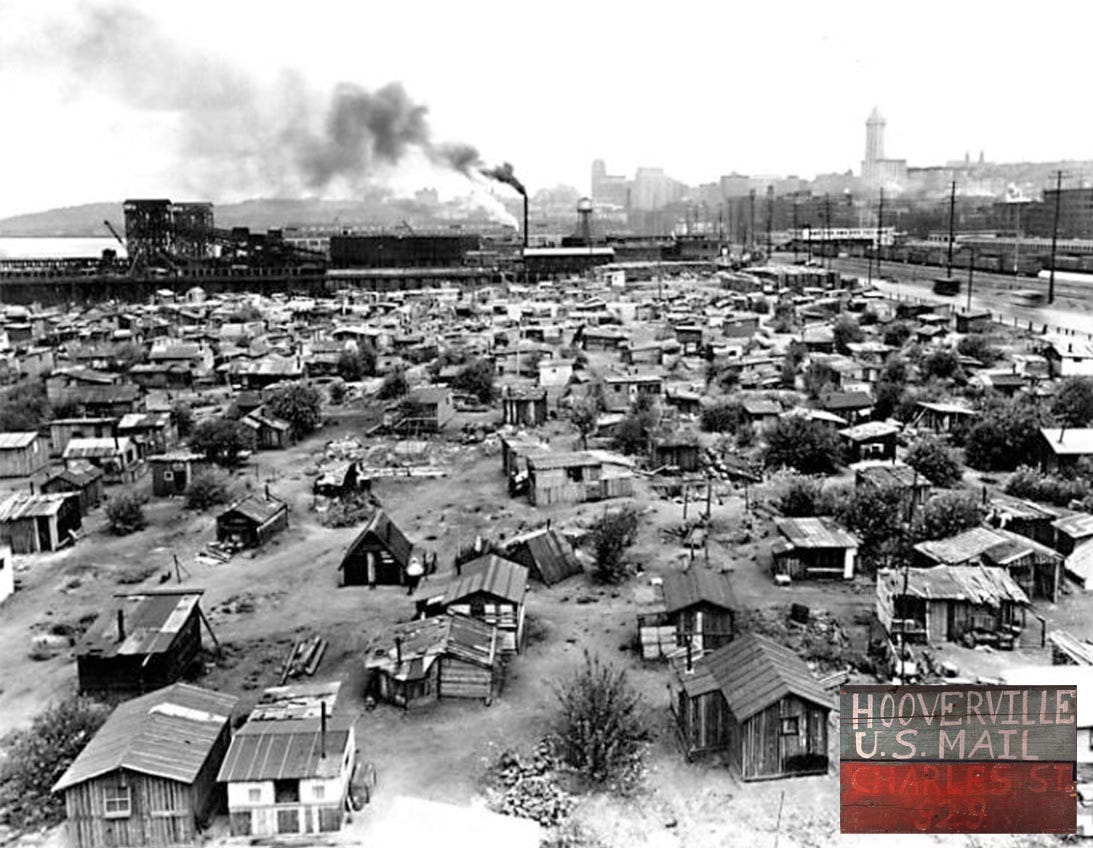

Save only for the Civil War, the Great Depression was the most dismal era in American history. And unlike the Civil War, the suffering of the American people was not in the service of a noble cause. It was simply a decade of grinding misery.

To get a flavour of that horrid time, following are a few passages taken from Freedom From Fear, the Pulitzer-winning history of America in the Great Depression and the Second World War, written by David M. Kennedy.

Unemployment and its close companion, reduced wages, were the most obvious and the most wounding of all the Depression’s effects. The government’s data showed that 25% of the work force, some thirteen million workers, including nearly 400,000 women, stood idle in 1933.

In Pennsylvania, Hickok's first destination, Governor Gifford Pinch had reported in the summer of 1932 that some 1,150,000 persons were ”totally unemployed." Many others were on "short hours." Only two-fifths of Pennsylvania's normal working population, Pinchot concluded, had full-time work. Elsewhere, the Ford Motor Company in Detroit had laid off more than two-thirds of its workers. Other giant industries followed suit. Westinghouse and General Electric in 1933 employed fewer than half as many workers as in 1929. In Birmingham, Alabama, another of Hickok's destinations, Congressman George Huddleston reported that only 8,000 of some 108,000 workers still had full-time employment in 1932; 25,000 had no work at all, and the remaining 75,000 counted themselves lucky to toil a few days per week. "Practically all," said Huddleston, “have had serious cuts in their wages and many of them do not average over $1.50 a day."

Some of the jobless never appeared on the relief rolls at all because they simply left the country. Thousands of immigrants forsook the fabled American land of promise and returned to their old countries. Some one hundred thousand American workers in 1931 applied for jobs in what appeared to be a newly promising land, Soviet Russia.

Nowhere did the Depression strike more savagely than in the American countryside. On America's farms, income had plummeted from $6 billion in what for farmers was the already lean year of 1929 to $2 billion in 1932. The net receipts from the wheat harvest in one Oklahoma county went from $1.2 million in 1931 to just $7,000 in 1933. Mississippi’s pathetic $239 per capita income in 1929 sank to $117 in 1933.

Accelerating foreclosures on defaulted home mortgages — 150,000 homeowners lost their property in 1930, 200,000 in 1931, 250,000 in 1932 — stripped millions of people of both shelter and life savings at a single stroke and menaced the balance sheets of thousands of surviving banks. Several states and some thirteen hundred municipalities, crushed by sinking real estate prices and consequently shrinking tax revenues, defaulted on their obligations to creditors, pinched their already scant social services, cut payrolls, and slashed pay-checks. Chicago was reduced to paying its teachers in tax warrants and then, in the winter of 1932-33, to paying them nothing at all.

“I saw old friends of mine — men I had been to school with — digging ditches and laying sewer pipe. They were wearing their regular business suits as they worked because they couldn’t afford overalls and rubber boots. If I ever thought, ‘there, but for the grace of God … ‘ it was right then.” —Frank Walker, president of the National Emergency Council, 1934

Miners who had earned seven dollars a day before the Crash now begged the pit-boss for the chance to squirm into thirty-inch coal seams for as little as one dollar a day. Men who had once loaded tons of coal per day grubbed around the base of the tipple for a few lumps of fuel to heat a meager supper — often nothing more than ‘bulldog gravy’ made of flour, water, and lard. The miner’s diet, said United Mine Workers president John L. Lewis, “is actually below domestic animal standards.”

… “Most of the women you see in camps are going without shoes or stockings… It’s fairly common to see children entirely naked…. Dysentery is so common that nobody says much about it.” “We begin losing our babies with dysentery in September,” one of Hickok’s informants casually remarked.

Two days after the election, on November 10, 1932, [Roosevelt’s] aide Adolf Berle had sketched a tentative legislative program for the new administration. Berle cautioned that "it must be remembered that by March 4 next we may have anything on our hands from a recovery to a revolution. The chance is about even either way.”

The president of the Farm Bureau Federation, among the most conservative of agricultural organizations, warned a Senate hearing in January: "Unless something is done for the American farmer we will have revolution in the countryside within twelve months."

Some observers, awed by Hitler's decisive march to power in Berlin, or by the enviable efficiency of Benito Mussolini’s regime in Rome or Josef Stalin’s in Moscow, urged that the dictators be imitated in America. Al Smith, once Roosevelt’s political mentor but now an increasingly venomous critic [also the 1928 Democratic candidate for president] compared the crisis of early 1933 to the ultimate emergency of war. "What does a democracy do in a war?” Smith asked. "It becomes a tyrant, a despot, a real monarch. In the Wold War," he said with much exaggeration, "we took our Constitution, wrapped it up and laid it on the shelf and left it there until it was over.” The Republican governor of Kansas declared that "even the iron hand of a national dictator is in preference to a paralytic stroke." The respected columnist Walter Lippmann, visiting Roosevelt at Warm Springs in late January 1933, told him with great earnestness: "The situation is critical, Franklin. You may have no alternative but to assume dictatorial power."

Amidst such desperation, radical ideas flourished. Some, like “technocracy,” sparked only brief enthusiasm. But there was a surge in interest in the two fresh new ideologies, communism and fascism, along with a strange brew of populism that combined elements of both with the vernacular of America — as exemplified by the Louisiana Senator Huey Long and the popular radio preacher Father Charles Coughlin.

By early 1935, Democratic officials believed that if Long, who had become a fierce critic of President Roosevelt’s, ran as an independent candidate for president, he could take at least 10% of the national vote in 1936, enough to hand the election to the Republicans. Other observers thought the threat was greater than that. Novelist Sinclair Lewis wrote It Can’t Happen Here, about a populist-cum-fascist who closely resembles Long taking power and turning America into a dictatorship. At a time when even major mainstream figures like Al Smith thought dictatorship was the medicine America needed, Lewis was surely right that, in fact, it could happen here.

Today, thanks to Donald Trump’s recent rally at Madison Square Garden, many people are familiar with the images of a 1939 American Nazi rally in the venue of the same name. A giant banner of George Washington between swastika banners. It’s stunning.

But Huey Long was assassinated in 1935 over a local political dispute in Louisiana and no comparable figure replaced him. The vast majority of the frightened, hungry masses of America never embraced political extremism and no communist, fascist, or populist demagogue ever came within a country mile of taking power during the Great Depression. And Franklin Roosevelt never assumed dictatorial powers.

Today could not be more different.

The unemployment rate in the Untied States is around 4%. I am 56 years old. That unemployment rate is among the lowest since I was born in 1968.

As for inflation, it never got to the levels of the 1970s, it was high only briefly, it came down faster in the United States than elsewhere, and it is now low and normal. Donald Trump will undoubtedly declare victory over inflation sometime in February, and hold a parade in his own honour, but in reality that victory was won months ago.

Economic growth is much stronger in the United States than its peers. Real wages are rising faster. A torrent of international investment is pouring into the United States, and American stock markets, because American economic prospects are the best in the world.

But set aside immediate conditions and look long term: The median American — the ordinary Joe who voted for Donald Trump — is so much wealthier and more comfortable than his equivalent during the Great Depression that America in 2024 would have sounded like an opium-fuelled fantasy to Americans in 1934.

And yet Americans today did what Americans then did not.

They voted for a demagogue whose attraction to violence and dictatorship is openly expressed, a man who traffics in dark, dehumanizing rhetoric, whose corruption and greed make Huey Long look like a medieval monk, who claims any election he may lose is rigged, and whose hostility to democracy has already led him to attempt to subvert one election and inspire a violent insurrection. They voted for a man who stepped out of a fever dream of Sinclair Lewis.

Americans today are not starving. Their children are not naked. They are not huddled in shacks desperately figuring out how they will survive another day.

Americans today are among the wealthiest, most fortunate people in history. And they succumbed to what the dirty, poor, desperate Americans of the Great Depression did not.

#2/ Progress can happen despite our stupidity

Now let’s shift a little further back in history, to the very beginning of the 20th century.

Industrialization was spreading rapidly. Economic growth was exploding, while international trade soared. Scientific and technological advances were spectacular and, at least in the industrializing countries, people’s living conditions were improving rapidly. The last speech US President William McKinley ever gave, at the World’s Fair in Buffalo, before his assassination in 1901, is almost giddy with excitement.

But then, in 1914, a terrorist shot an Austrian aristocrat, statesmen made blunder after blunder, and the world plunged into an abyss. The Great War that followed was industrial slaughter, as all our magnificent science and technology was enlisted in the service of death.

There is no better symbol of the turn humanity took than Fritz Haber: In the years before the war, the brilliant German scientist developed a method to extract nitrogen from the air, creating artificial fertilizer and ensuring that agricultural abundance, not starvation, would be our future; when the war broke out, Haber turned his genius to the development of the gas that clawed at soldiers’ eyes and liquified their lungs.

When the war drew to its miserable close, nations mostly turned inward, especially in the United States, where “America first” and the isolationist belief that America could largely ignore the rest of the world dominated American politics for two decades. Russia succumbed to Lenin’s Communists. In 1922, Mussolini took his “fascists” to power. Despite the horrors of the war, both governments promoted highly militarized societies.

“The roaring twenties” are immortalized only because the United States enjoyed five boom years — and a dangerous stock market bubble — that produced classic novels still read today. In reality, for most of the world, the 1920s were grim. And they were followed by the devastation of the Great Depression, which was made so much worse than it had to be because statesmen accelerated all the worst trends — restricting international trade and cooperation, closing economies, embracing militarism.

Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 and … You know the rest. Appeasement, war, genocide. A new weapon capable of incinerating cities in a flash.

Fritz Haber didn’t live to see all that. Haber was a Jew. He fled Germany and died of a heart attack, homeless, in 1934. In Germany, Haber’s research led to the creation of the pesticide Zyklon B. The Nazis used Zyklon B in the gas chambers of the death camps.

The great British writer H.G. Wells was long a techno-optimist of Silicon Valley proportion but by 1946 he had been beaten into submission by this ceaseless parade of depravity. “The end of everything we call life is at hand and cannot be evaded,” he moaned. That was a common sentiment among the intelligentsia of the day.

Why am I recapping this litany of misery?

To cheer you up, of course.

You see, over the quarter-century between 1914 and 1945, humanity was — how shall I put this? — incredibly fucking stupid.

We made one idiotic decision after another. It was as if we had a collective death wish. In fact, if we had wanted to destroy the world and ourselves — if we genuinely hated humans and wanted us wiped out — it would have been hard to do better than we did.

This was stupidity that absolutely dwarfs the idiocy now sweeping through politics, in the United States and elsewhere. This was the mother of all stupidity.

And yet…

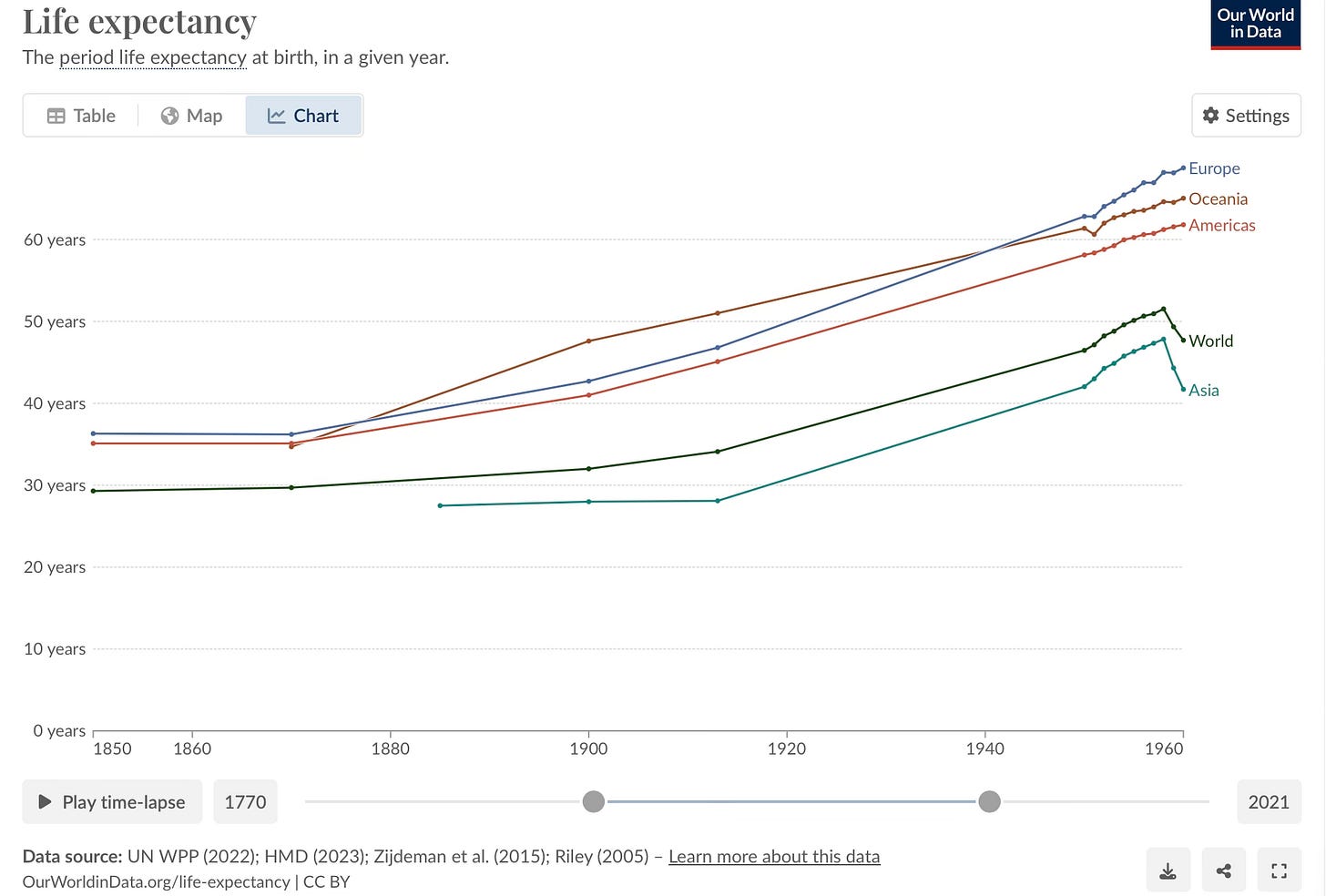

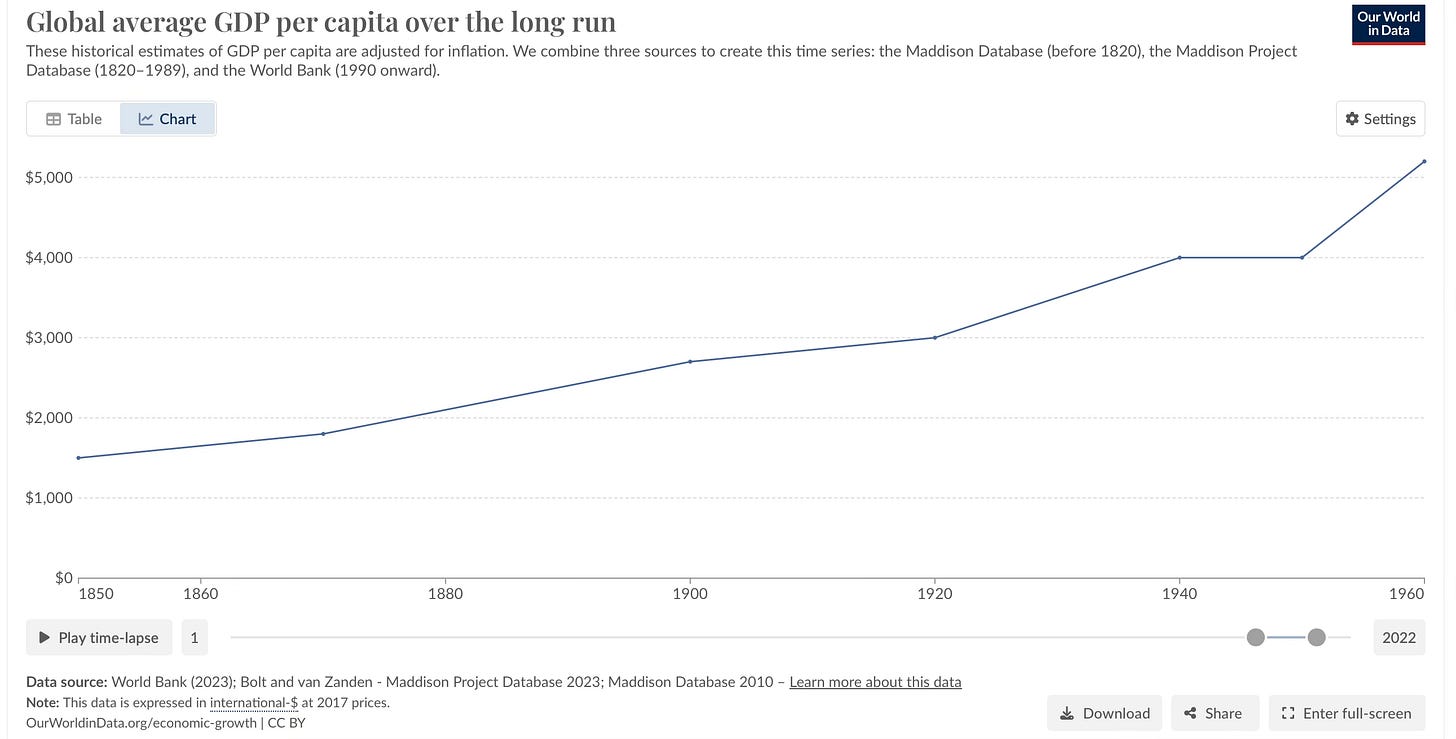

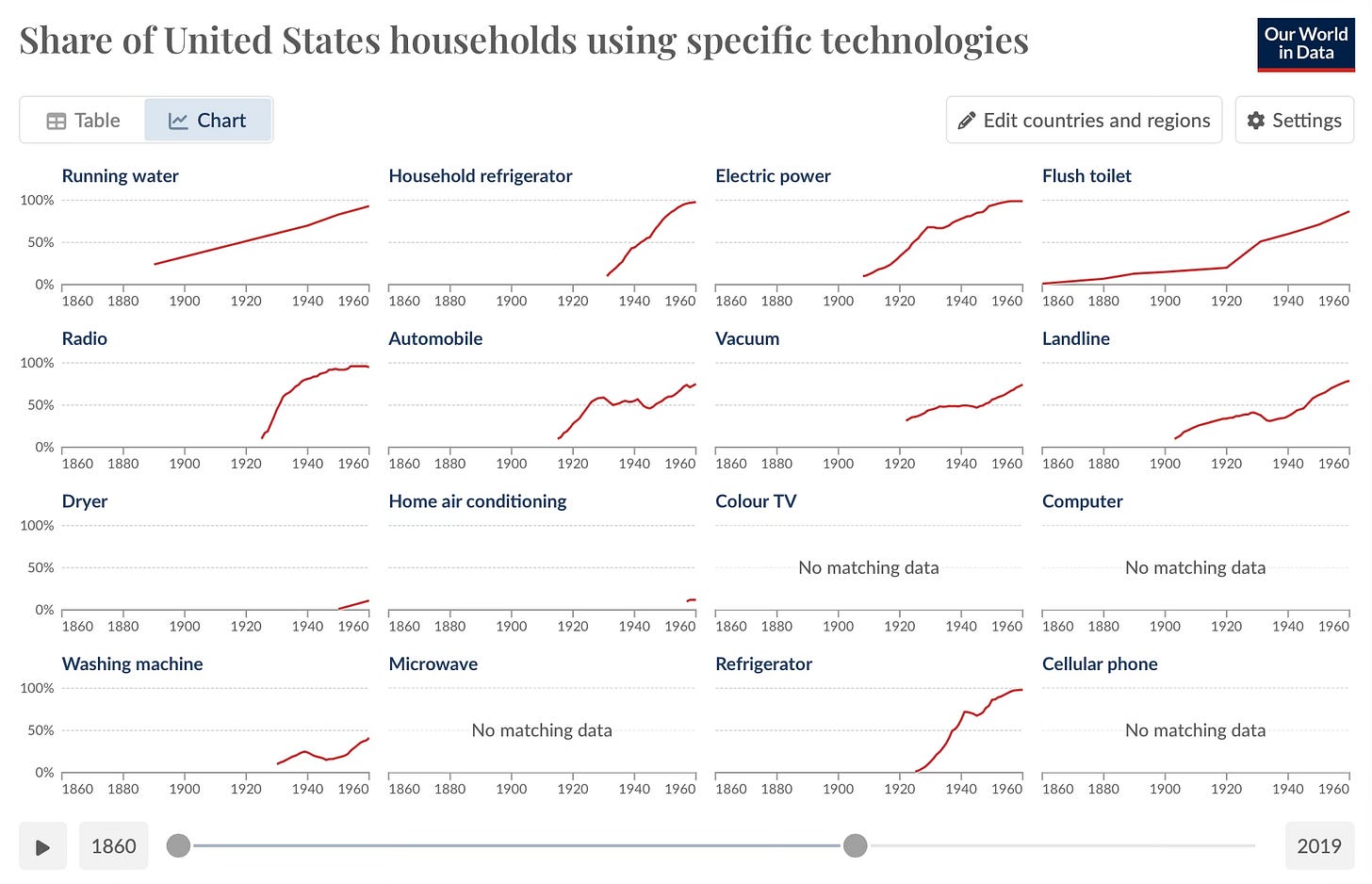

Following is a series of charts with highlights of human development between 1850 to 1960. (My thanks to the inimitable Our World In Data. Such a fun and useful resource.)

Focus on the period between 1914 and 1945 in particular. Do you see the world going to hell?

In some of these charts, you can see setbacks, particularly during the 1930s. But in context, those setbacks look more like … wobbles. They don’t significantly alter the trend lines.

The simple truth is that all the monumental stupidity our species exhibited between 1914 and 1945 did little to slow, much less stop, the advance of progress. People suffered horribly thanks to our stupidity. They died by the tens of millions. It was tragedy on a scale that defies words. Yet for all our bombs and hate and madness, when this era ended, humanity had actually made significant advances.

What does this mean for today? It proves that it is at least possible, if we are very fortunate, for humanity to make spectacularly foolish decisions without derailing progress and leaving our children and grandchildren worse off.

Which seems like a good thing to keep in mind today.

KBO, everyone.

Sir, I agree that Trump is crude and he is lewd but now he is renewed. So we have him for four more years.

I think that one needs to think of him in another way: he is a master bullshitter but everyone, particularly the electorate, knows that he is a bullshitter.

I expect fully that within these next four years we will see evidence of his age related decline, much as Sleepy Joe exhibited, and that is in addition to the pathologies to which he is already known to experience. The only saving grace is that he cannot run for re-election. J.D. Vance in 2028, anyone?

Now, how will Trump govern? As a Canadian - like you - I will be watching and considering. You note that you are 56; I am 73 so you are just a kid, but a much wiser kid than I. Nevertheless, as my late mother-in-law used to say, "This too shall pass." [Perhaps she was meaning me?]

Good article. I am a fan of stepping back and looking at the current moment in historical perspective, as a general principle of maintaining positive mental health. I recommended Steven Pinker's Enlightenment Now to some family recently for the same reason.

A reincarnated America First movement, with actual power this time, is obviously not what the world needs right now, but it is what we've got. Its not condescending to point that out.