"Leader of the Free World"

Americans keep calling the president that. Does it make sense? A little history is in order.

In her response to President Joe Biden’s fiery State of the Union Address, Republican Senator Katie Britt declared herself shocked and appalled. “The free world deserves better than a dithering and diminished leader,” she huffed.

Democrats and Republicans will disagree on whether “dithering and diminished” accurately describes President Biden. But they will agree that “the free world” deserves better than that. More importantly, they will agree with the underlying point that the President of the United States is the leader of the free world.

That is a truism in American politics, after all. Even reporters state it as simple fact when they want to underscore the importance of the president’s office.

“This is a race to be the leader of the free world.” — Nikki Haley’s campaign manager, Betsey Ankney, The New York Times, February 5, 2024.

“Delighted by his access to the president, Meadows frequently put Trump on speakerphone — one time doing so in the middle of a speech he was giving — so that others could appreciate how close he was to the leader of the free world.” —New York Times political reporter Robert Draper in his profile of Mark Meadows, President Trump’s chief of staff, The New York Times, February 8, 2024.

But when Senator Britt used that classic trope she got me thinking.

The term has been kicking around for ages, clearly. I’m old enough to get the senior’s discount at my local weed store — if I were so inclined — and I’ve heard the President called “the leader of the free world” my whole life. But how old is that term, exactly? How did it come to prominence? Has it evolved?

And the important question: Given the historical context of its origin, does it even make sense any more?

To have a look around, I used the database newspapers.com.

The earliest use I found will probably surprise you. I know it surprised me.

It was published in a newspaper with the magnificent name of The Vermont Cynic. Still in print, it’s the student newspaper of the University of Vermont, in Burlington, Vermont. The story in question appeared on April 28, 1917.

That date is significant: A few weeks earlier, the United States had abandoned neutrality, declared war on Germany, and joined what would later be called the First World War as an ally of Britain and France.

The spring meeting of the New York Alumni Association had been held the previous evening, the newspaper reported. The food was excellent. The Class of ‘93 led some strange school chant. Then the Class of ‘14 did their own strange chant. Finally, “cigars were lighted” and the guest speaker was introduced: He was Major Charles William Gordon, a chaplain in the Canadian Army.

”He brought home to those present in a deeply impressive way fundamental causes of the war and the ideals — American ideals — for which the British Empire and her allies were fighting. It was because their ideals were similar, he said, that Britain and America would be leaders of the free world that would arise after the war.”

Whether Gordon actually used the phrase “leaders of the free world” I can’t say. But there it is. The first reference in an American newspaper to America as a “leader of the free world.”

It did not catch on.

It didn’t catch on for a good reason. While the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson tried valiantly to get the United States to take a seat at the table of Great Powers, during the war and after, Republicans rejected any talk of American leadership and instead demanded a return to traditional American isolationism. (I sketched this history recently.) Republicans took the White House in 1920 and held onto it until the election of 1932. Both American policy and society became deeply isolationist, and remained so until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor finally forced the United States into the Second World War. In that era, calling the President the “leader of the free world,” or even “a” leader, would not only have been absurd. To many, it would have sounded downright unpatriotic.

(And Charles Gordon, the man ahead of his time? He is mostly forgotten now, which is a shame. Among other accomplishments, he helped lead the drive to create the United Church of Canada. But he was internationally famous for the novels he wrote — exciting, patriotic, wholesome — under the pen name of “Ralph Connor.” The retired Ottawa Citizen columnist Charles Gordon is his grandson. I knew Charlie way back when I started at the Citizen. He’s a mensch. This has been another instalment of Six Degrees of Historical Separation.)

So where did “leader of the free world” really get started? Not when you think. Or where.

The catastrophic German blitz through Western Europe and France in the spring of 1940 left Great Britain isolated and vulnerable to a degree it hadn’t been since the peak of Napoleon’s power. When Winston Churchill became prime minister, and a negotiated peace was ruled out, the idea of the beleaguered free peoples holding out against a tide of enslavement took hold. It was spontaneous, to an extent. But it was also calculated — and promoted by the British government for a very specific reason.

Consider this story from a British newspaper:

The brutal massacres of innocent hostages in France, coupled with the systematic campaign of extermination in the other occupied countries are condemned to-day in the sternest words by Mr. Churchill and Mr. Roosevelt.

The leaders of the free world voice the general horror of all free men at the develish (sic) excesses of the Nazi hordes.

That story is dated October 26, 1941 — more than a month before Pearl Harbor. The United States was still neutral. While Roosevelt had declared a state of emergency and was sending a steady flow of aid to Britain, and he clearly wanted to take the United States to war, popular support for direct intervention was still too weak to overcome the determined opposition of isolationists.

By framing Britain and the United States as “the free world,” led jointly by their leaders, the British government portrayed Britain and the United States as de facto allies. More importantly, it used American language in a way British officials knew would appeal to Americans, strengthening Roosevelt’s hand. In a word, it was propaganda.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and Germany declared war on the United States, America was in. And the Allies were often called, and called themselves, “the united nations” or “the free world.” The latter was a little awkward given that the third major ally was the Soviet Union, but accuracy is not propaganda’s concern. As a result, gems like the following sentence occasionally appeared in British and American newspapers: “As Russia enters on its third year of war Marshal Stalin, her man of destiny, has been receiving inspiring messages from the other leaders of the free world.” If it ain’t fascist, it’s free.

Now, at last, we get to where you thought we’d start: the Cold War.

After victory in the Second World War, the Soviet Union installed puppet governments in Central and Eastern Europe. In 1946, now out of office, Churchill gave a speech in Missouri in which he declared that an “iron curtain” had descended across Europe “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic.” (Churchill apparently had a high opinion of Americans’ knowledge of geography.) In the years following, the phrase “Cold War” rapidly grew popular as a description of the growing hostility between the former allies.

To go with “Cold War,” the American press dusted off “free world” and turned it into a self-flattering shorthand for the liberal democracies squaring off against the Soviet bloc.

But by the late 1940s, British economic, military, and political power had plunged. And by the time NATO was formed in 1950, there was clearly only one remaining “leader of the free world.” It was the United States. Which made the President the “leader of the free world.

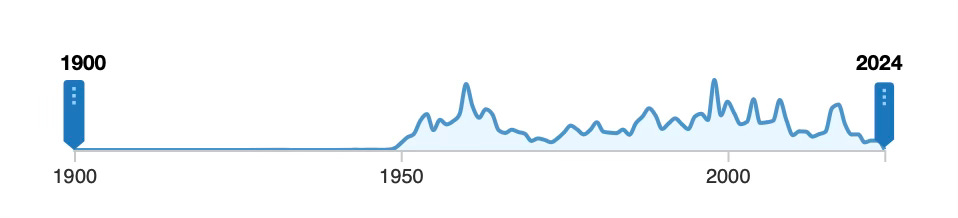

That phrase spread rapidly, too. Here’s a chart of “leader of the free world” in American newspapers:

Dwight Eisenhower played a major role in that rise.

Ike had been Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during the Second World War. He had been instrumental in the creation of NATO and he became its first commanding officer in 1950. Then, in 1952, he defeated an isolationist senator for the Republican nomination and he won the presidential election.

When that happened, on November 4, 1952, it was unmistakable that the United States had reached a major watershed. Four days later, the phrase “leader of the free world” first appeared in The New York Times.

The author was Anne O’Hare McCormick, a Times editorialist. And she absolutely nailed the moment.

These pictures illustrate two striking facts of the 1952 campaign. One is the broadening popular base on which the United States policy rests. The other is the widening reverberations of the American debate. There were no forgotten men or submerged fractions in this election; in the niagara is of words that flooded the country, every segment of the population was appealed to and every one had its say. And in distant lands, people argued over issues and candidates almost as hotly as we did. They took sides. In some places governments held their breath and postponed important decisions until a vote was counted.

This means that more people outside the United States recognize that as America goes, so go the free nations. Likewise it means that more people inside the United States exercise influence on international policy. The American voters, in other words, whether or not they thought beyond local issues, assumed last Tuesday the double responsibility of choosing a president for this country, and the man predestined to be the leader of the free world for four decisive years. (emphasis mine)

There hasn’t been an election since 1952 in which those words could not be repeated.

Even today — especially today — people “in distant lands” pay astonishingly close attention to the United States today while foreign governments hold their breath and postpone important decisions. American voters (let’s be generous) are not renowned for their international concern and cosmopolitan perspective, but whether they think “beyond local issues” or not, those voters still determine who leads the American executive. And the American executive unavoidably influences much of what happens around the world.

But are American voters still choosing “the leader of the free world?”

In 1952, there was an alliance of nations that very much looked to the United States for leadership in what they viewed as an existential struggle with a hostile foreign power. However much British pride may have been bruised, however much it may have galled the French, the Germans, the Italians, the Japanese or anyone else, people who saw themselves as part of an alliance facing off against the Soviet Union had to see President Dwight Eisenhower as their ultimate leader— their supreme commander, if you will — in that struggle.

When the Soviet Union crumbled in 1992, and the Cold War became history, one might reasonably have expected that to end. NATO was a defensive alliance with nothing to defend against, after all.

But in the late 1990s, the American superpower got upgraded to “hyperpower” and the United States became what Bill Clinton’s Secretary of State Madeleine Albright famously called “the indispensable nation.” Famine in Somalia? Genocide in Bosnia or Rwanda? Tsunami in the Indian Ocean? Earthquake in Haiti? Pirates in the Red Sea?

Who you gonna call?

Sometimes the United States screwed up. Sometimes it arrived late. Or it didn’t answer the phone. But still the nations of the world called. There was no one else, after all.

Take a look at that chart, above. References to the United States or the American president as “leader of the free world” actually hit new highs in the Clinton era. The “free world” may not have needed a leader to stand against the Red Army. But Americans were more sure than ever that their guy was the free world’s guy. And that wasn’t unreasonable. The United States had built the international order and the United States was the ultimate protector and guarantor of that order. It was the Pax Americana and far from withdrawing from the world, America was doing more than ever. Calling the American president “the leader of the free world” seemed like small compensation.

Almost one quarter of a century has passed since that era, however. And important things have changed.

Today, of course, Vladimir Putin’s cosplay fantasies — he’s Peter the Great restoring the mighty Russian Empire — have solved NATO’s existential crisis. Even the Germans, the most delusional of Europe’s delusional pacifists, now recognize they need a strong military. And American leadership. So is it 1952 all over again? Doesn’t that ensure the American president will continue to be “leader of the free world?”

Not quite. Because something else has changed. Go back to 2001 and the arrival of the “Dubya” administration, as we old journalists remember the George W. Bush years.

American “hyperpower” spawned American hubris. And as we have known since the ancient Greeks, hubris makes people stupid.

A series of monumentally stupid decisions — Iraq, Afghanistan, the whole foolish “global war on terrorism” — damaged America’s international reputation, drained some dimensions of American power, and produced a “G Zero” world, as Ian Bremmer dubbed it, meaning that instead of a bipolar world dominated by two superpowers, or a unipolar world dominated by one hyperpower, the world is in important ways not dominated by anybody. Which is dangerous. In the same years, a lot of Americans understandably became sick of being the world’s first responders. Toss in the decline of manufacturing as production shifted to China, add the cynicism produced by a global financial meltdown and severe recession that resulted in none of the Wall Street fatcats responsible going to prison, and you have the conditions for an angry populist of the loudest, dumbest, angriest sort. Enter Donald Trump. Now eliminate the people and institutions who held Trump in check, fully Trumpify the Republican Party, and it’s no surprise the musty old word “isolationism” is back into the news.

As I explained previously, I don’t think Trump and his party are isolationist in the original sense of that term. But they sure as hell are not internationalist in the way every post-World War Two president has been internationalist. In a very meaningful sense, Donald Trump and Dwight Eisenhower are such polar opposites that it is a slur on a great man’s name to include them in the same sentence for any reason except to note how opposite they are.

So American voters really do have a fundamental choice ahead, and not only for all the obvious domestic reasons.

Joe Biden and the Democratic Party are offering a continuation of a model that has been in place since 1952. (You could even say the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944 is the benchmark. But I digress.) America built the international order. America leads the international order. And an America-led NATO is the military keystone of that international order. So if Biden is re-elected, one could reasonably say it is four more years for “the leader of the free world.”

But Donald Trump and his Trumpified Republican Party would at least seek to blow up much, or even most, of that model, starting with the NATO alliance. (Whether they would succeed is another matter. An order that is three-quarters of a century old is deeply entrenched.) The one component that would indisputably remain, in a Trumpian world, is the size and reach of the American military. How Trump would use that power is as unpredictable as his impulses. Remember, this is a man who loudly and proudly said he supported the use of torture and only backed down when his Secretary of Defense, a former four-star Marine Corps general, told him that using torture would endanger American servicemen. That Secretary of Defense came to despise Trump, as have all competent people who have worked with Trump, and so he, like most of the other checks on Trump’s zaniness, is long gone. Which means nothing is off the table. Nothing.

In a Trumpian world, the United States would still be an economic and military giant and the decisions of the President of the United States would still reverberate around the world. But would the President still be “leader of the free world”? That depends how you define leadership. If being a leader means being the strongest guy on the block, or the one others fear most, yes, the president would still be “leader of the free world.”

I suspect that for Trump and at least some of his fans, that is what defines a leader. But I’m certain that Dwight Eisenhower would have been horrified by that mentality. He would have considered it thuggish and recalled Josef Stalin’s dismissal of the Pope with the quip, “how many divisions does he have?” That’s a dictator’s mentality, Ike would say. And someone who thinks like a dictator should never live in the White House.

I’m also confident every president since Eisenhower, Republican and Democrat, would have agreed.

There’s another way of thinking about this, one that occurs to startlingly few Americans: Maybe we could explore the views of the free world’s resident who cannot vote for the free world’s leader because they are not American? (People like your correspondent, who is Canadian.)

Here is a strong hint of what those people would say.

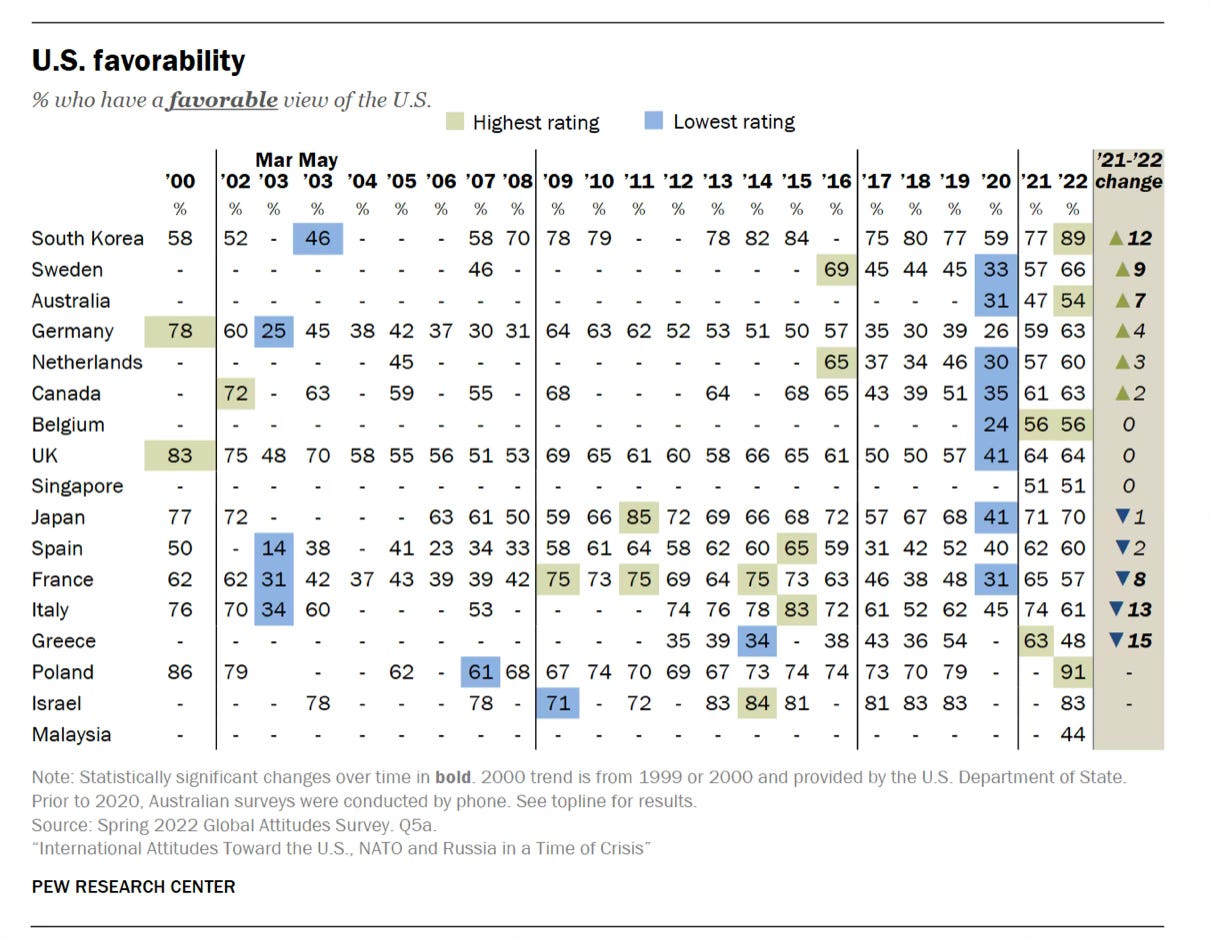

The trend couldn’t be clearer. When Donald Trump became president, the international stature of the United States immediately plunged, and it set record lows during his presidency. The moment Trump was replaced by Joe Biden, America’s reputation shot back up. (The secondary trend: George Bush’s invasion of Iraq turned much of the world against the United States. See my comment about “monumental stupidity,” above.)

Let me be blunt: Most residents of the free world outside the United States fear and despise Donald Trump. We breathed a giant, collective sigh of relief when he was evicted from the White House.

If Donald Trump is returned to the presidency — despite the incompetence, the lies, the assaults, the bullying, the insurrection, the impeachments, charges, and trials — Americans may continue calling their president “leader of the free world.” But this is a man who, in his first administration, when he was restrained somewhat by competent people, behaved like a drunken and belligerent Viktor Orban. Now that the competent people have been jettisoned, and the restraints on his power in a second administration are falling away one by one, Trump has gone so far as to say he would “encourage” Russia to invade … our countries. Us.

True, Trump did say he would only do that if he was dissatisfied with our defence spending. But that’s like your neighbour saying that if you don’t put a fresh coat of paint on your house, and take better care of your front yard, he will call up a gang he knows and “encourage” them to break down your door, rape your wife, and murder your children. When your neighbour talks like that, whether the change he is asking you to make is reasonable or not is — I think you will agree — beside the point.

If Donald Trump becomes president again, and Americans call him “leader of the free world” within earshot of the free world outside the United States, expect bitter laughter. Or a tirade. Or both.

But that is for the uncertain future.

In the meantime, we foreigners can only watch. And hold our breath.

Churchill was a master of the language and had no qualms about crafting a phrase as a trap or stealing good material. For instance, he swiped "iron curtain" from Josef Goebbels, who first used it in Das Reich on Feb. 5, 1945, and in his diary the next month.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1991/09/26/origin-of-the-term-iron-curtain/eba1de60-f26d-4c40-a069-37229c04e2b9/

Accurate description of, and warning about, Trump.