"Mokusatsu" and the Atomic Bomb

The old debate about Hiroshima and Nagasaki marginalizes the Japanese perspective. Add that and it's clear miscommunication and misunderstanding played tragic roles in how history unfolded.

From Dan Gardner:

Following is a guest post I am delighted to share with PastPresentFuture readers. I’m sure you’ll agree it’s timely. And unsettling.

The author is

, a British historian of Japan, professor at the University of Edinburgh, occasional BBC broadcaster, and author of popular histories of Japan. I’m reading and thoroughly enjoying his History of Modern Japan, which begins with the forcible opening of Japan by American warships in 1853 and the race to modernize. I highly recommend it for those who, like me, want a good introduction to a society that is as bewilderingly complex as it is highly consequential. Also note has his own Substack newsletter, so be sure to click on his name and subscribe.Now, over to Christopher Harding.

On July 26, 1945 — eighty years ago today — the leaders of the USA, Great Britain and China issued the Potsdam Declaration, setting out the terms for Japan’s surrender in World War II.

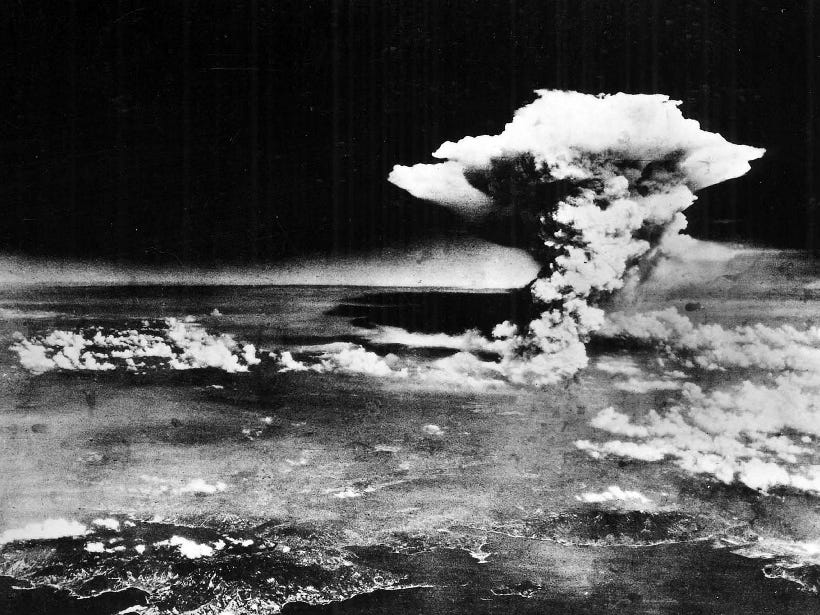

Had this moment been seized upon by Japan, most people around the world would never have heard of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Our sense of the potency of atomic weapons might still rest only on nuclear tests, not their deployment in war.

So why didn’t Japan act?

On the face of it, the terms of the Potsdam Declaration appeared clear enough:

“Unconditional surrender.”

The “eliminat[ion] for all time [of] the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest.”

“Convincing proof that Japan’s war-making power is destroyed.”

The relinquishing of Japan’s colonies and the temporary Allied occupation of parts of Japan.

Justice meted out against war criminals. Ordinary Japanese soldiers to return to civilian life.

The revival of democracy and of fundamental freedoms and human rights.

And should Japan’s leaders refuse? Those famous words: “prompt and utter destruction.”

The Japanese couldn’t have known about the Trinity test, conducted just ten days earlier, which confirmed the viability of what physicists the world over had suspected since the 1930s — that nuclear fission could be harnessed to create a “super-bomb.”

And yet the trend of the war had been obvious for months. The USA was out-producing Japan in war material many times over and was rapidly reversing Japanese gains made in the early months after Pearl Harbor. In Japan itself, people were starving, disease-ridden and deeply pessimistic about the future. Rationing had become so extreme that they were being taught how to use sawdust as a supplement for flour in making bread. Fuel was so scarce that in Okinawa, people were said to be reading at night by the light of phosphorescent sea creatures.

So it wasn’t steely resolve amongst the people of Japan that prevented the country’s leaders from accepting immediately the Allies’ terms. Instead, it was something at once prosaic and heart-breaking: failure of communication.

Of two kinds.

First, the Potsdam Declaration was not presented to the Japanese Foreign Ministry. Instead, it was communicated to Japan via the American media. This may have been one reason why the Japanese side, too, decided to respond via the media.

“I believe the Joint Proclamation by the three countries is nothing but a rehash of the Cairo Declaration,” the Japanese prime minister told reporters. “As for the Government, it does not find any important value in it, and there is no other recourse but mokusatsu and to resolutely fight for the successful conclusion of this war.”

The key word there is “mokusatsu,” which has a literal meaning of “silence” — but also other meanings, including ignoring something that is trivial or beneath you.

The Japanese press took the government’s mokusatsu to mean an emphatic “no.” The US press took note and drew the same conclusion. So did the Allied governments.

It was not an unreasonable inference. The Allies knew, after all, that the newspaper Yomiuri had printed a comment piece under the headline “Laughable Surrender Conditions to Japan.” In a country where the wartime press was tightly controlled, could that happen if the government was inclined to take the Potsdam Declaration seriously? Surely not. So that must express the Japanese government’s view. Or so the Allies believed.

But had the Japanese government intended to express a firm rejection?

That question gets to the heart of the second failure of communication, which ran much deeper and broader in Japanese life. It had origins of a sort in Heaven itself.

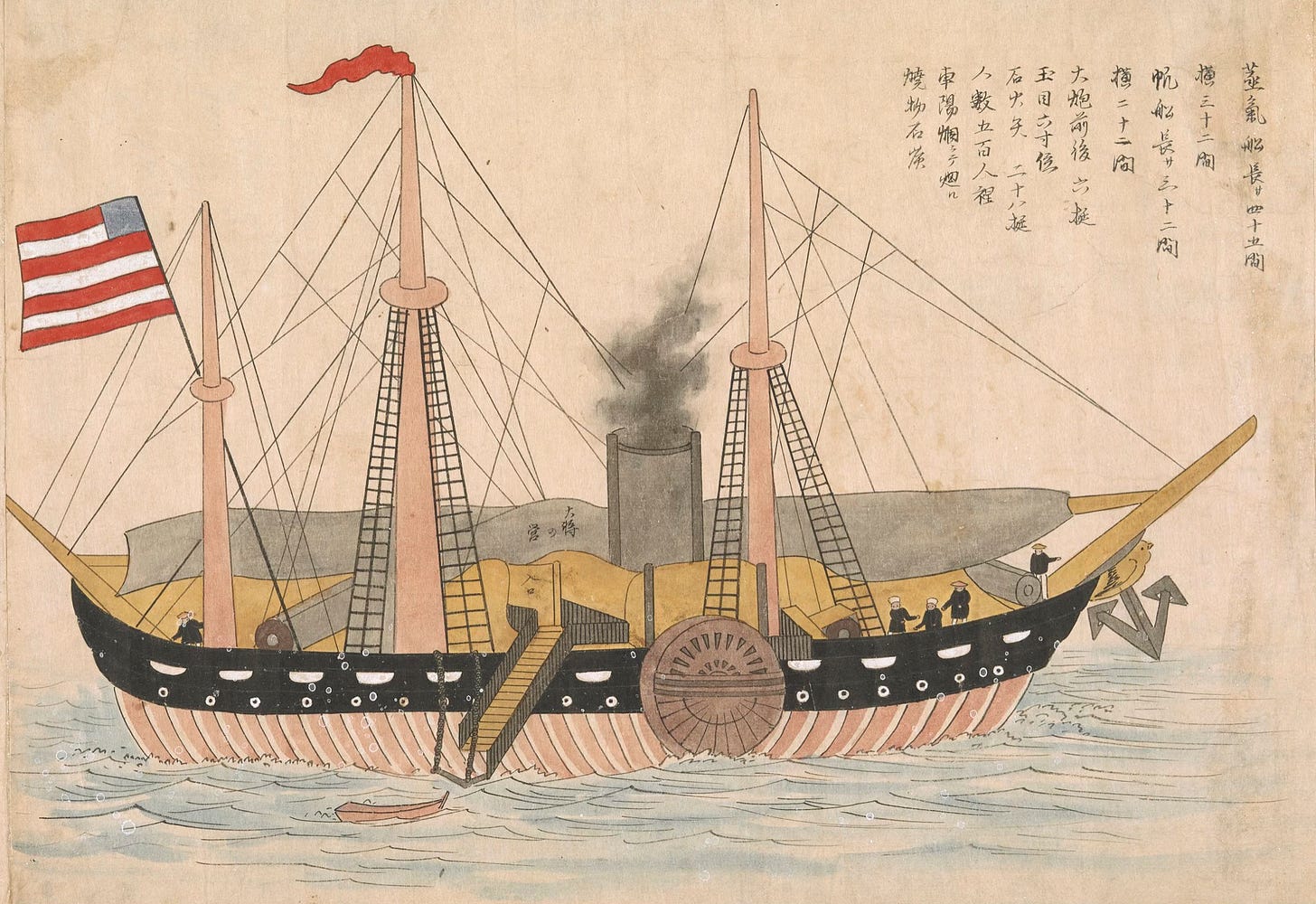

Modern Japan was built at a furious pace, in the latter part of the 19th century. Japan’s equivalent of America’s founding fathers were young ex-samurai who responded to the forcible opening of the country by an American fleet in 1853 by overthrowing the old regime in a civil war and set about building a new country that could hold its own in the modern world.

One of the biggest problems they faced was that no-one in Japan had heard of them.

Why on earth would people consent to pay taxes, send their children to newly-built schools (when they could be helping out at home) and allow family members to be conscripted to the armed forces - all because a bunch of nobodies said so?

Japan’s new leaders needed a figurehead. They found one in the Emperor.

The Japanese imperial line went back, unbroken, around 1500 years. For some, its origins lay with the gods, as the emperors were said to be descended from the Sun Goddess Amaterasu.

During World War II, Allied propaganda made much of the idea that the barbaric and still semi-feudal Japanese were all in mystical thrall to this Emperor, prepared to sacrifice their lives in order to do his bidding. They were worrying about the wrong thing. What the Allies ought to have been worrying about was the potential for catastrophic failures of leadership and clear communication in a country where a semi-divine figure is theoretically at the very top of politics.

A diagram showing how Japan’s constitution worked, in theory, would feature arrows pointing from everyone - politicians, civil servants, army, navy, courts and prime minister - up towards the Emperor. And not only did the Emperor hold ultimate power — again, in theory — but many of these other important individuals and institutions reported only to the Emperor. They had little direct responsibility towards one another.

When times were good, they co-operated. When they began to want different things from one another, governance in Japan could — and did — fall apart.

As far back as the mid-1920s, military figures had started to say that quisling diplomats were selling Japan down the river in international negotiations. They criticised businessmen, too, for looking after themselves while mistreating the rural poor (from amongst whom the Army recruited heavily). It was a renegade army unit that kicked off the Manchurian Incident in 1931, launching a false-flag attack they pinned on Chinese soldiers. This was the pretext for taking over Manchuria — and starting the slide toward what became the Second World War.

On and on, across the 1930s, senior military figures pressurised and then sidelined civilian politicians. Such was the power of the armed forces under the constitution - not to mention the brute fact of their monopoly on the use of violence - that Japanese democracy steadily ebbed away.

By the time of the Potsdam Declaration, senior civilian figures in Japan had been calling for a negotiated surrender for some time. Most in the Army were opposed. That put the Emperor in an almost impossible situation. Hirohito saw himself as a constitutional monarch, not an autocrat. He desperately wanted those below him in the constitutional pecking order to agree on a path of action and then simply seek his blessing.

Critics of Hirohito argue that in fact he was personally very much in favour of the war — at least while Japan was winning it — and that he was amongst those pushing back against calls to end the conflict. We will probably never know, but what is clear is that Japanese decision-making and communications between its elites had been poor for a very long time. And now those things faced their sternest test.

Hopeless optimism complicated Japan’s calculations. Japan and the Soviet Union were still not yet at war and the Soviet Union was not a signatory to the Potsdam Declaration. Indeed, the Soviets didn’t even see a copy until after it was issued. Might this, wondered some in Tokyo, mean that Stalin could still be appealed to as an intermediary?

At the same time, the British electorate had just rewarded Winston Churchill for his extraordinary wartime leadership by giving him the sack. Might a new, incoming British government find a little room in their hearts for Japan?

Optimism aside, Japan’s leaders, hamstrung by their constitution and by the culture of military involvement in politics that had been allowed to fester over decades, simply couldn’t agree to a unified response to the Potsdam Declaration.

Some leaders wanted more time to explore a negotiated rather than an “unconditional” surrender.

Others worried that there had been no mention of the fate of the Emperor in the Declaration, and the idea of him being tried as a war criminal, of a 1500-year old imperial line ending with a man swinging by his neck from a rope, was unthinkable.

For Hirohito, there was a raw and well-founded fear for his life. But there was also a sense of duty to his ancestors to protect and preserve the throne.

So Japanese leaders dithered, delayed and assured one another that there was still plenty of time to see how things might play out. The firm rejection the Allies thought Japan had delivered was a mirage. Japan was silent because Japan did not decide.

Meanwhile, “Little Boy” was being assembled and the Enola Gay was flying test runs. A taste of “prompt and utter destruction” was just days away.

Extremely interesting article and thought provoking. The contents of the Potsdam Declaration echo in today’s chaos in America.

“The revival of democracy and of fundamental freedoms and human rights.”

The State that urged the Japanese to return to ‘freedoms and human rights’ has been seized by characters who would now argue to have those words stricken from the Declaration. How ironic.

In the context of the summer of 1945, the Japanese not deciding to surrender meant deciding to continue fighting. A crucial feature of the situation, interestingly, was poor bureaucratic design—a war cabinet with even numbers of officials that required a majority to change course, allowing a 3-3 deadlock to keep the war going EVEN AFTER the atomic bombings.

A good summary of how the summer’s events played out on the Japanese side is here:

https://nationalinterest.org/feature/what-oppenheimer-left-out-206722