Over the years, I’ve found that a remarkable number of people are hesitant to acknowledge progress. Life span. Wealth. Goods and services. The comforts of our homes. Mention that any of these is better than ever in human history, for the average person in the developed world, and increasingly in the developing world, too, and you can expect blowback. Even if you are careful to emphasize that you do not think we live in paradise, that you agree we still face very grave problems, and that, yes, some things that matter are certainly worse today than in the past. If you simply say “some things are better,” you invite scoffing, incredulity, and scorn. Or worse.

I once said in a talk that air quality in most cities in the developed world is far better than it was in the mid-20th century and after I finished a woman marched up to me, almost vibrating with anger. She demanded to know my sources. I cited one. She dismissed it with a huff. I suggested others. Same reaction. Finally I said she could consult any reliable source she liked and she would discover that my statement was as controversial as claiming that average temperatures are lower in winter than summer. She left as angry as she came.

And that’s for material progress, the sort of thing that can be settled by unambiguous numbers. Make a claim for moral progress — for the idea that, yes, in some ways, the average person behaves better than in the past — and the denial will be considerably more vigorous. The erudite will sneer and quote Candide — “all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds” — even if you explicitly insist that you are absolutely not saying anything like that. The middlebrows will call you Pollyanna. Others will say worse.

But sometimes it has to be said. This is one of those times.

A week ago, President Joe Biden signed a bill making lynching a federal hate crime. In a sense, it wasn’t a big deal. The bill changed little about the legal realities. Nor does it mean much in practical terms, as lynching is, blessedly, close to extinct in America and investigated and punished when it happens, in stark contrast with the past. (For modern examples, see the murders of James Byrd in 1998 and Ahmaud Arbery in 2020.)

And yet black commentators — and only black commentators, as far as I can make out — saw enormous significance in it. And they were right to.

To explain why, let me tell you about baseball legend John McGraw.

After a successful career as a player in the 1890s, McGraw spent 30 years as the manager of the New York Giants. He won ten pennants and three World Series. In an era when America was obsessed with baseball, he was a towering figure. Even today, baseball aficionados consider him one of the greats.

Like a lot of professional athletes and managers, John McGraw had a good luck charm that he carried in his pocket. It wasn’t a rabbit’s foot. It was a little piece of rope — a piece taken from the noose that had been used to lynch a black man. Fans gave it to McGraw, who, apparently, was delighted.

And it seems he wasn’t the only one in baseball who thought a murder weapon was a dandy souvenir. Following is a United Press story from Mobile, Alabama, dated March 19th, 1909, which ran under the headline, Lynching Rope As A Mascot:

As a token of good luck, rare in these parts and still rarer in the North, Manager Lajoie, of the Naps, has received a section of rope used at a lynching. A local rooter presented it. Accompanying it was the following information: “A portion of the rope used to lynch the negro Richard Robertson, Saturday morning, January 23.”

On the morning of the lynching a masked mob of white men broke into he jail, and overpowered the jailors and inside of three minutes they left the jail and the negro was hanged to a tree, half a mile from the Mobile county Jail. It is said by the Spanish of olden times that the best of luck came to the possessor of any portion of a rope used for lynching.

Lajoie turned it over to the Cleveland club for framing.

As lynching souvenirs go, a piece of the rope was modest. Many lynchings, particularly in the late 19th century, drew enormous crowds. In the excitement, ladies were known to create their own little souvenirs by dipping handkerchiefs in the victims’ blood. Small body parts, such as fingers and toes, sometimes served the same purpose.

These are not the inscrutable ways of distant people in medieval or ancient times. This was the behaviour of Americans in the lifetime of my grandparents.

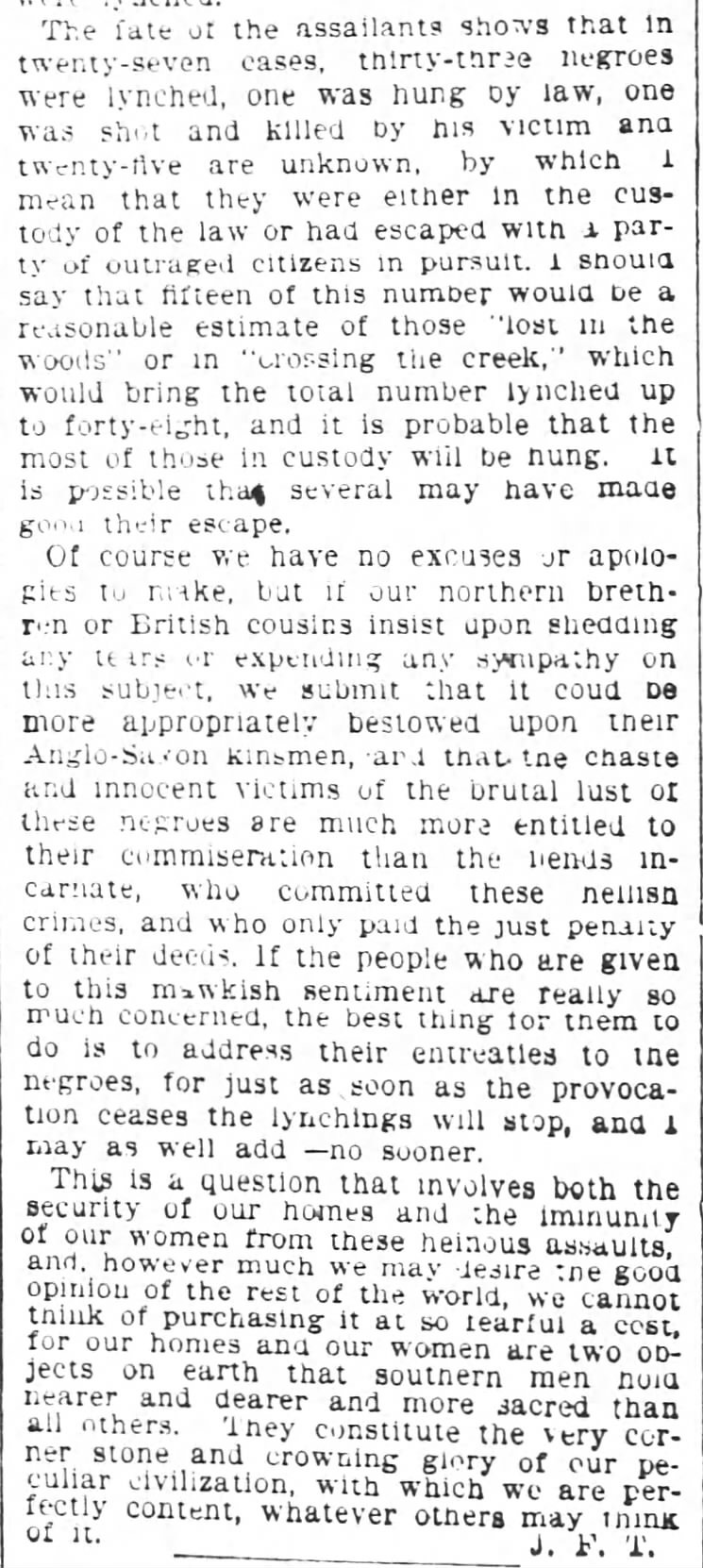

In the late 19 century, lynching was particularly common in the south and was thus condemned widely in the north, and in the United Kingdom, as the lingering spirit of slavery. Southerners openly defended the practice. Even in the pages of newspapers, where language was tempered by the need to keep up appearances, the arguments they offered make for stunning reading today. Here is one, written by the editor of the Atlanta Constitution and published on June 17, 1894.

JFT’s defence of lynching against the “mawkish sentiment” of those who objected is nothing more than “they deserve it.” That rumours and accusations may not be accurate, that there may be other motivations at work, or that investigation by lawful authorities and due process for the accused is the proper way to handle alleged crimes seems not to have crossed his mind. At least not in this public statement addressed to Yankees and Brits. What he said in private can only be imagined. And this man, remember, was the editor of a major regional newspaper.

Along with racism and stunning cruelty, lynching represented the failure of governments to maintain control of criminal justice. Particularly in the late 19th century, victims were predominantly black but anyone accused of a crime could be at risk, particularly if they came from a marginalized population. The biggest mass lynching in American history happened in New Orleans in 1891, after Italian immigrants accused of murdering the police chief were acquitted at trial. An enormous mob, including many prominent citizens, broke into the jail where the men were being held and systematically shot them. Eleven men died.

But at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, criminal justice systems professionalized and strengthened, mob justice waned, and lynching declined. Everywhere but the South, that is. And among every population but black men. Lynching became exclusively a form of terrorism to enforce the racial caste system. When whites were lynched, it was for helping blacks. Or opposing lynching. In the South, what Jim Crow could not do was left to mobs with ropes.

It was one thing for officials in Washington to turn a blind eye to the disenfranchisement of blacks in the South. It was another to ignore torture and murder. The first bill to make lynching a federal crime — so federal authorities would be empowered to stop what state and local officials manifestly could not or would not — was introduced in 1900, by George Henry White, the only black man then serving in Congress. It failed to pass. Many more attempts to pass legislation were made. They all failed.

How could Congress refuse to act? By the first decades of the 20th century, sentiments had turned against lynching to such an extent that the blunt argument made by the editor of the Atlanta Constitution in 1894 — they deserve it — was no longer one that could be uttered in public by respectable persons. Opponents focused on the constitution, which gave states jurisdiction over criminal law. If the federal government could make lynching a federal crime, they argued, it could make anything a federal crime, and seize control of a major state power. To white southerners, that raised the spectre of Reconstruction and federal troops enforcing the law in their states. To them, that was more horrifying than lynching.

Here is a newspaper account — taken from the Tampa Daily Times, December 20, 1921 — of a speech in Congress delivered by Democratic Congressman James Benjamin Aswell of Louisiana. The bill he spoke to would have made lynching a federal crime, fine counties where lynchings took place for failing to enforce the law, and imprison local officials who colluded with the lynchers.

Reading Aswell’s comments — “the trustworthy, dependable negro of the south … has no interest in such legislation” — it’s hard not to imagine the stereotype of the southern sheriff or the plantation bigot. But Aswell was a teacher and educator. Before becoming a Congressman, he was Louisiana Superintendent of Education and a university president.

In 1930, the sociologist Arthur F. Raper published a careful investigation of lynching that concluded 3,724 people had been lynched between 1889 and 1930. “Over four-fifths of those were Negroes, less than one-sixth of whom were accused of rape. Practically all of the lynchers were native-born whites.” But the rate of lynchings was clearly declining, even in the South. In the late 19th century, there were more than 100 lynchings each year, and over 200 in some years. In 1930, there were 21 lynchings.

By 1939, when Billie Holiday recorded the mournful ballad Strange Fruit — written by Abel Meeropol, the son of immigrant Russian Jews — the annual toll was in the single digits.

The first year with no lynchings in the United States was 1952.

In 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy, was lynched in Mississippi.

In 2022, the United States Senate unanimously passed the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act making lynching a federal crime. That would have been historic in any year. But in a year when Senators likely couldn’t find unanimous agreement on the number of seasons, it was especially so.

When President Joe Biden signed the legislation, it became law — 122 years after the first of so many failed attempts to to make that moment happen.

“This is a day to rejoice that indeed the arc of the moral universe is very, very long, but it does ultimately bend toward justice,” noted Senator Cory Booker, paraphrasing Martin Luther King’s famous line.

There’s a phrase for what King described. It is “moral progress.”

Good reminder and hopefully this law will never be repealed!

Franklin Zimring published a book in 2003, entitles "The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment". https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/426490?journalCode=ssr

I immediately thought of it reading your piece, because Zimring painstakingly traces the correlation between those States in the U.S. where lynchings were "acceptable" in the past, and their continued use of capital punishment today. Conclusion? It hasn't really abated much, the form and process has just changed to make it seem less morally blameworthy.