Musk's Problem? No Alanbrooke.

Even the wise need someone to tell them when they are foolish

Close observers of MuskWorld, including Kara Swisher, who was a friend of Musk’s for many years, have noted that Elon Musk made the classic mistake of the powerful: He surrounded himself with like-minded friends, family, and hangers-on who do far too much cheerleading for the great man and far too little pushing back.

That has worked as well as it usually does, and thanks to Musk’s X addiction we can all see at least some of the consequences play out daily. Ridiculous statements. Gratuitous insults and public beefs. Diffusion of focus. Conflicting goals. Superficial thinking and poorly informed decisions. Brands in flame (literally) and an empire in jeopardy.

Steve Davis is emblematic of Musk’s mistake.

An aeronautics engineer who has worked for decades with Musk, Davis is reportedly loyal to a fault: Once “a fun outside-the-box” thinker, says an old friend, he is now Musk’s “blind servant.” During the campaign, Musk had him lead his superpac despite the fact that this self-professed fan of Ayn Rand admitted “I know nothing about politics.” Now he is Musk’s point-man as DOGE races through the government, swinging chainsaws at agencies and programs that Musk and his handful of engineers barely understand — with results that range from the predictably shambolic to the predictably tragic.

The tiger-trap Musk fell into is as old as civilization itself.

A man — it’s usually a man — does the hard work of assembling information, seeing problems from multiple perspectives, and analyzing with extreme care. Thanks to the rigour of his thinking, he gets excellent results. Success brings power. He learns to trust his judgement.

This is all fine if the process ends there, but it commonly does not.

Instead, this man’s trust in his own judgement grows like a cancer until he believes his judgements are excellent not because of the hard work and careful thought he puts into them. He believes his judgements are excellent because they come from him. The very fact that he believes something to be true is proof that it is.

At that point, he inevitably becomes more impulsive. And obstinate. After all, his judgements are superior, so if others say he is wrong, or evidence grows that he is wrong, he should dismiss that and dig in.

Just as inevitably, his judgements get worse, because the very qualities that made his judgement excellent in the first place have been jettisoned and replaced with blind confidence.

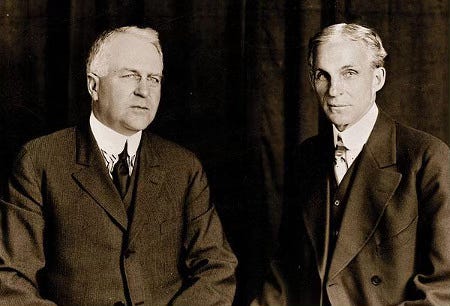

In business, this is sometimes called “CEO disease.” There are countless examples, but for me the exemplar of the phenomenon is Henry Ford, who revolutionized manufacturing and built an empire but became so convinced of his infallibility on every subject under the sun that he nearly lost everything.

The ancient Greeks called this hubris. As the Greeks constantly warned, hubris angers Nemesis. And Nemesis humbles even the mightiest.

The solution to this trap is as ancient as the trap itself: Always have smart, independent, tough-minded advisors who test your thinking and speak up without hesitation when you are foolish.

In that sense, Henry Ford’s opposite was Winston Churchill.

After becoming prime minister in 1940, when Europe had fallen to the Nazis and Britain faced invasion, Churchill appointed Sir Alan Brooke the new Chief of the Imperial Staff — his top military advisor.

Brooke was not an old friend of Churchill’s, much less a crony. He was simply the best general the British had, as both his reputation among his peers and his recent performance in France attested. He was also known to be hard on everybody. Himself. His subordinates. His superiors. He pushed and pushed and constantly demanded nothing less than excellence.

Churchill knew that before he appointed Alanbrooke (who was confusingly dubbed “Viscount Alanbrooke,” so he is referred to as “Alanbrooke” as if that were his surname.) He had even personally experienced it.

After the Dunkirk evacuation, when the remainder of British forces need to be organized for evacuation, Alanbrooke was in France leading the effort. Churchill got him on the phone and gave him orders. Alanbrooke explained at length and in detail why the prime minister was wrong. “All right, I agree with you,” Churchill concluded. Then he made Alanbrooke his top general.

That was their relationship in a vignette.

Alanbrooke and Churchill made each other miserable. Churchill was forever pitching ideas ranging from the brilliant to the mad (more of the latter than the former) while Alanbrooke was the hard-headed strategist and analyst who kept the big picture in view while digging up the details that explained why Churchill’s latest enthusiasm was folly. Churchill pushed back. Alanbrooke pushed back. Churchill pushed back. Alanbrooke pushed back. It never ended.

Of course the two men bitched about each other. Each said and wrote harsh words about and to the other, along with other words of respect. But it was a creative dialectic. Churchill proposed. Alanbrooke criticized. And Britain marched to victory.

Alanbrooke summed up the paradoxical nature of their relationship with his judgement about Churchill: “Without him, England was lost for a certainty, with him England has been on the verge of disaster time and again.”

But remember, Churchill was the boss. The only way such a relationship can work is for the boss to see the need for it. To deliberately construct it. And to make the most of it — by really listening to what the advisor says and always having the humility to say, “you are right and I am wrong.”

Churchill had that humility and never lost it.

Then there’s Elon.

A few days ago, Senator Mark Kelly — former NASA astronaut and decorated fighter pilot — tweeted on X that he had just visited Ukraine and “what I saw proved to me we can’t give up on the Ukrainian people. Everyone wants this war to end, but any agreement has to protect Ukraine’s security and can’t be a giveaway to [Vladimir] Putin.” On X, Musk sent the following response to his nearly quarter-billion followers: “You are a traitor.”

There are countless examples like that. Stupid. Squalid. Loathsome. And every one of them a distraction from the goals Musk has set himself. Lots are even more ridiculous, more pointless, more self-defeating. And some are far more consequential — not least the whole DOGE travesty.

Elon Musk is a man who thinks he is an expert on every subject and his every thought is a pearl of truth that needs not even a moment’s vetting before it is shared or acted on. He has no Alanbrooke because he sees no need for an Alanbrooke.

That sound you hear is not a burning Tesla. It is Nemesis sharpening her knife. We know how this story goes.

There’s even an earlier version of it that involves another revolutionary car maker.

Aside from historians, few remember that Henry Ford did not build the Ford empire alone. James Couzens was nominally Ford’s employee, but in reality was Ford’s partner. Couzens focussed on business; Ford managed engineering and manufacturing. It was that partnership to took the Ford Motor Company from one of thousands of small car makers to a titan that dominated the industry.

But by 1915, when Ford had become a celebrity and hero, and he was constantly asked his opinion about the issues of the day, his CEO disease was already well-advanced. When he decided to use the company’s own internal newspaper to publicize his views about contentious political issues, Couzens told him, no, you can’t. It’s bad for the company.

Ford blew up at Couzens. Couzens quit.

In the years that followed, Henry Ford allowed his ego, pig-headedness, and political obsessions to consume more and more of his time and energy. He became a polarizing figure even as he neglected the company he founded. Ford stagnated, lost its dominance, and steadily fell further and further behind.

It wouldn’t revive until after the Second World War. And Ford’s death.

All major leaders need a Couzens or an Alanbrooke. But only the truly great know it.

Two related points came to mind as I read your excellent article.

First, is what has sometimes been referred to as the Myth of the Garage - the idea that important advancements come from the brain of one or two brilliant people toiling away heroically against the odds. The reality is always that there was much more involved in the success from outside funding to networking and experience gained elsewhere which helps to account for the success. It doesn’t necessarily take away from the insight or innovation of specific individuals. And thus, the most successful tend to be those who can take information and advice, including criticism, from others.

Second, there seems to have been a steady increase in the average number of authors of scientific and engineering studies over the past 4 years. It has been argued that this reflects an increasing need to be multidisciplinary in the pursuit of innovation. So, there is considerable value in having someone who is successful in one field look beyond that field for insights and inspiration. It just appears that it is unlikely any one man can have the ability to out-think and out-know everyone else in all fields.

Another historical example of relevance to your article and to these points is likely Edison.

Excellent piece. In the same vein, 'Team of Rivals' by Kearns (on Lincoln's cabinet) is a classic account of leadership, or even (a more minor key) the political sagacity in WLM King's Cabinet-making process, so very well described by Granatstein in 'Canada's War'. We also have intimate knowledge of the disputatious but ultimately effective US inner circle during the Cuban Missile Crisis, very nearly word-for-word, moment by moment. And of course the Roman slave, running alongside the victorious general, whispering of mortality amidst wild triumph.....