In an earlier post today, I mentioned “negativity bias,” which is our hard-wired tendency to notice and remember negative information more than good news. In many contexts, negativity bias serves us well. It often makes perfect sense to pay more attention to and more vividly remember the things that hurt us more than those that don’t. That was especially true in the ancient environments in which our brains evolved.

But today? Negativity bias can and often does distort our perceptions of the world in ways that lead not only to misunderstanding but bad decisions. So my thanks to the World Economic Forum and McKinsey for providing a handy illustration.

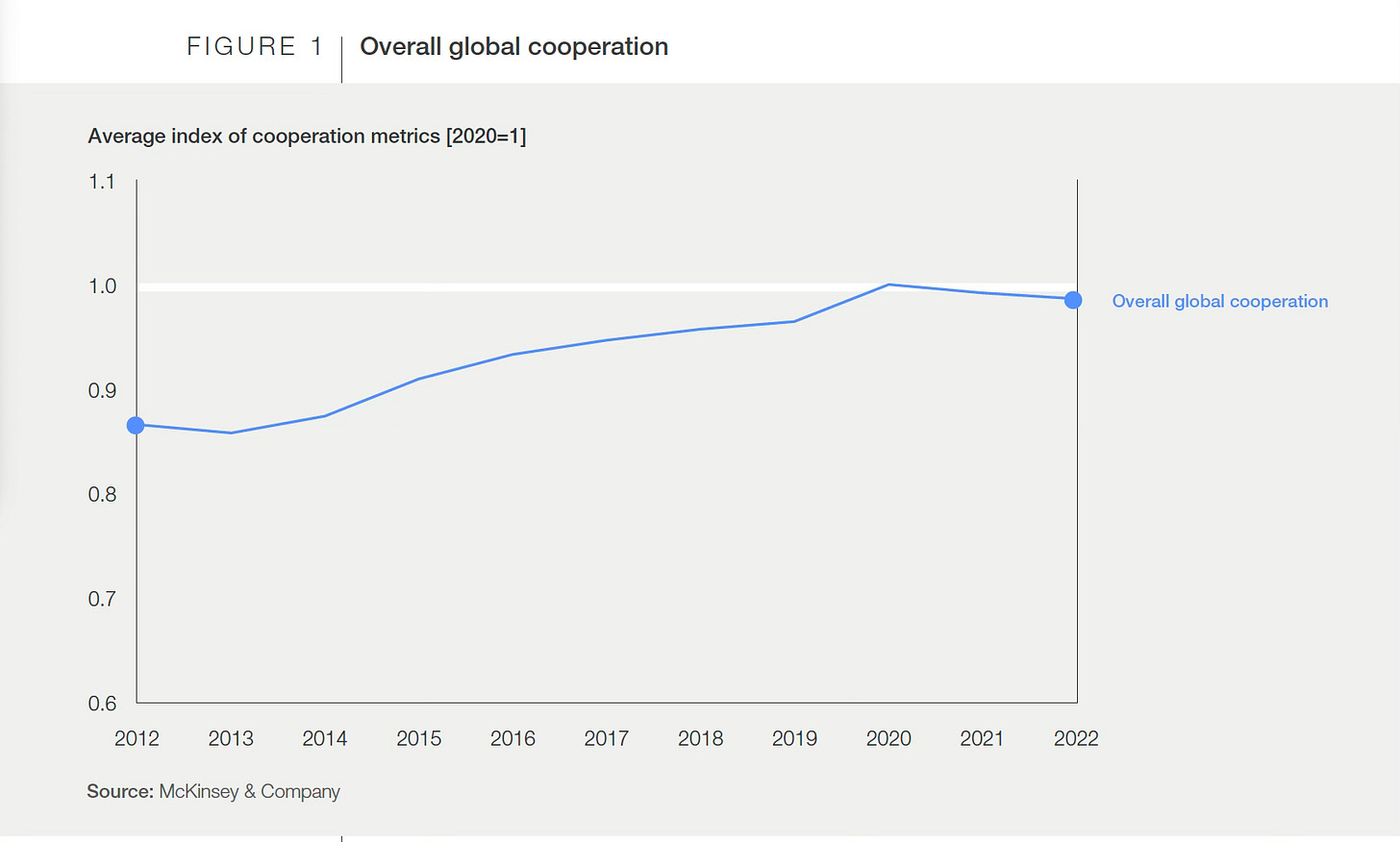

The WEF’s just-released “Global Cooperation Barometer” is an attempt to create an index of global cooperation. It strikes me as a reasonable and worthy effort, with global cooperation subdivided into five categories — trade and capital, innovation and technology, climate and natural capital, health and wellness, peace and security — each of which is measured with a handful of metrics. The Barometer is indexed to 2020 and the researchers quite sensibly calculated the numbers backward to 2012, so we can see the trend lines from 2012 to 2022.

Before I get to how the report frames its findings, let me skip straight to the final, aggregate score over the past decade.

You may remember 2012 was far from an untroubled time. Several European countries teetered on the edge of bankruptcy and there was widespread fear that if Europe went over the cliff it would take the rest of the world with it. And the US was hardly in a position to save the day as it continued the long, painful struggle to climb out of the pit of the Great Recession. Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party had revealed deep discontent on the lest and the right. There was a sense that American politics was coming unglued (a motif that has become as predictably repetitious as a Philip Glass composition.)

So what do you see in that chart?

I see a whole lot of good news! That lines goes up and up and up. There is a slight downtick coincident with the pandemic but it hardly takes away from a generally positive trend. Doubt that? Imagine it’s 2012. You’re told this is how a measure of global cooperation will look over the coming decade. Are you happy? Oh yes.

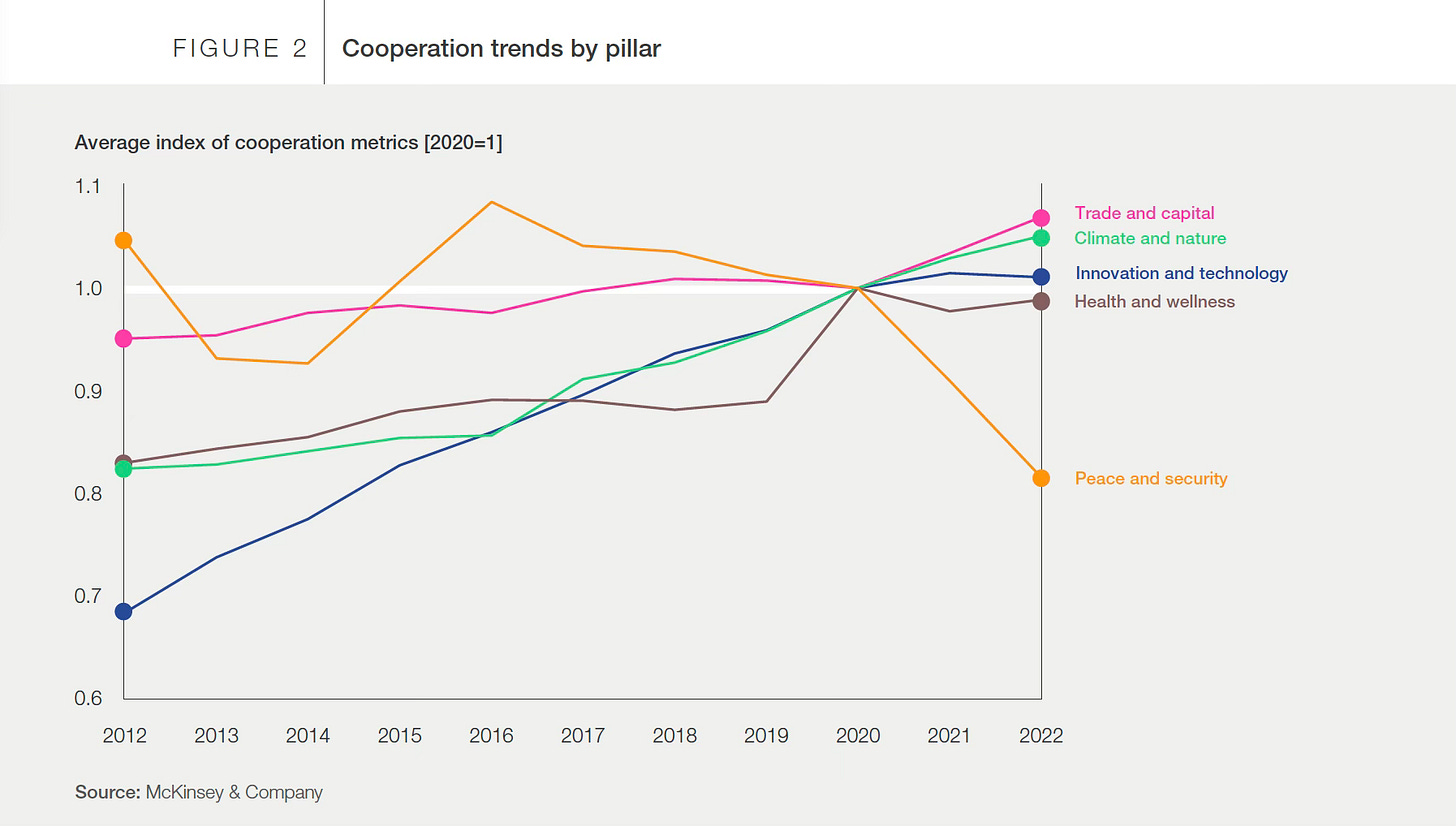

But of course that’s the aggregate number. What about each of the five components of the index?

Here they are.

So what do we see here? Four of the components are either modestly or strongly positive. “Peace and security” is the one exception — hardly a surprise if you follow the news — with a worrying drop between 2020 and 2022 after holding mostly steady.

How can we sum up these findings? Yes, there’s some clearly bad news in there. But overall, the index delivers mostly good news. (And I say that as someone who thought the picture would be grimmer, to be honest. These numbers are a lot rosier than I expected.)

But…

How do WEF and McKinsey frame their own conclusions?

Here is the opening of the letter than introduces the report.

The launch of the Global Cooperation Barometer comes at the start of a crucial year, amid a period of immense geopolitical, geo-economic and market uncertainty, when the bedrock of what was once a stable global system is shifting underfoot. Leaders in the public and private sectors will need to gain fluency in the dynamics driving the changes to not just stabilize their position, but to be equipped to shape a beneficial future.

It is no secret that the current global context is concerning, as heightened competition and conflict appear to be replacing cooperation. The result is that new power dynamics, changing demographic realities and breakthrough frontier technologies are raising the temperature on long-simmering distrust rather than fueling opportunities for benefit. Many businesses are responding to these complicated – and often fraught – geopolitical developments by shifting operations and facilities closer to home.

Yet, although the world is heading towards a dangerous divide by some measures, elsewhere there are prospects for and progress on cooperative arrangements.

Allow me to summarize in plain language: “The world is scary! It wasn’t in the past. But now it’s so uncertain! And scary! And complex! But it’s not all bad news….”

This is an inversion of what the numbers plainly show. Instead of “it’s mostly good news with some worrying signs,” it becomes “it’s bad and scary but don’t be discouraged because there’s also some good news.”

So how do media stories frame the report?

Here’s one headline: “Global cooperation declined 2 percent from 2020 to 2022: WEF.”

And here’s the lede from a Reuters commentary: “There is an overwhelming sense that the world is sliding toward a more competitive and even confrontational era as wars rage around the world, companies reassess supply chains, and frontier technologies become frontlines of strategic rivalry. Yet, in the face of these signs of divide, there are also signs that global cooperation is not only taking place but is more resilient in some respects than expected.”

I have yet to find a headline along the lines of “global cooperation up significantly over past decade, WEF report finds.”

So what’s going on here? As usual, I suspect a mix of influences is at work.

For one thing, the established, constantly repeated narrative is that the world is going to hell in a hand basket and a report that concludes global cooperation has greatly improved over the past decade is pure cognitive dissonance. If the focus is instead put on what’s negative in the report, with the positive made secondary, it fits the narrative, and provides an encouraging message at the finish. That’s the psychological sweet spot.

And, well, it’s Davos. Like Swiss fondue and champagne, expressions of alarm are to be expected. Whenever the world’s deep (and rich) thinkers gather to ponder the state of the world, they conclude it’s more uncertain than ever. The big buzz last year was around the “polycrisis.” Remember the “polycrisis?” I wrote about it. But whether it has a new buzzphrase or not, the mood is always, “holy hell, things are uncertain,” but rather than conclude that radical uncertainty is a permanent condition of modern human existence and has been for at least a century, they decide, every year, that radical uncertainty must be a scary new thing. (There’s an easy way to improve the quality of all discussion at Davos: Require attendees to watch a lecture about hindsight bias before being admitted.)

There’s also a little marketing going on. The WEF and McKinsey want to do more with their report than accurately describe reality. They want reporters to report on it. They also want top government officials and executives at multinational corporations to read it — and further consult with the WEF and McKinsey, who would be more than happy to do so for the appropriate fee. A report that says, “things are looking generally pretty good, with some exceptions” isn’t going to deliver on those scores.

But most fundamentally, I believe, it’s negativity bias at work.

If I show you pictures of ten faces, nine of them smiling, one scowling, which one is your eye drawn to? Which one do you remember? Of course.

Similarly, if I have five metrics and four are trending positive, but one recently turned negative, where does your focus go? What do you remember?

We are modern, educated, and sophisticated. But even those of us who travel on private jets are, like our ancestors, primates with severe hair-loss. And heavily prioritizing the negative continues to be a basic feature of human nature.

Caveat homo sapiens.

Might it not also be that this penchant for interest in negativity also tends to be married to an attraction to novelty ? If I look at the graph with the sub-categories displayed and four were pointing negatively while one was sharply positive, it is likely that my eyes will first be drawn to the outlier. And in much of our lives, no matter how bad and anxious we feel, what is novel are the markedly negative developments or events.

I keep coming back to how everyone now looks at the nineties as a golden age of peace and prosperity. It sure didn't feel that way while Rwanda and the Balkans were on fire, extremists bombed a federal building in OKC in response to the deadly standoff in Waco, and grunge music and gangsta rap dominated the charts. (Though in the latter case, music took a massive turn toward upbeat pop by the end of the decade.)