No Billionaire Is "Self-Made"

A critical lesson from the Gilded Age that we need today.

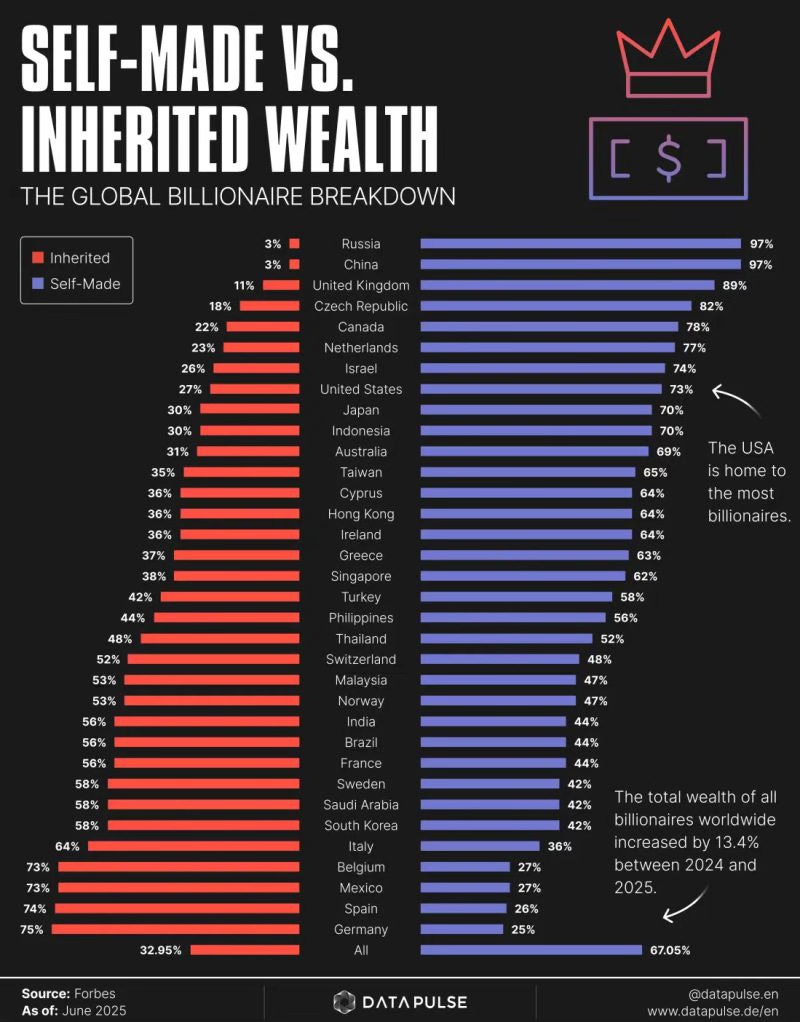

I recently came across an interesting chart on LinkedIn, though the data and terminology come from Forbes magazine and its famous list of the world’s wealthiest people.

Note the analytical framework: “self-made” versus “inherited.” There is no option three. Anyone with a billion dollars or more must be one or the other.

You probably find nothing noteworthy in that. It is, after all, how we routinely talk about the wealthy in public discourse. You probably also attach a degree of moral judgement to the two categories. That, too, is very common.

“Inherited” wealth is fine, as far as it goes, but it says little about the person. “Inherited” billionaires simply won the birth lottery. We may envy them. But most of us neither admire nor despise them.

The “self-made” billionaire is something else entirely.

The self-made billionaire conjured the vision, spotted the opportunity, seized the initiative, and won a fortune. His wealth is irrefutable proof of his intelligence and drive. He is a winner. He is someone to be admired, feted, and emulated, which is why there is a cottage industry devoted to gleaning the wisdom and learning the lessons of these paragons of excellence.

True, this judgement is far from universal (the people with “every billionaire is a policy mistake” bumper stickers don’t believe it) but in my experience and reading it is extremely widespread, particularly in the United States, where a “self-made” billionaire is automatically qualified to offer sage counsel or hold high office. Recall the current president — who had never held public office or run a large organization before deciding he should be president — responding to Hillary Clinton’s accusation that he didn’t pay his taxes. “That makes me smart,” he boasted. And recall who won that election.

There’s much more at work here than language, naturally. But language is hard at work.

Call a billionaire “self-made” and you can’t help but picture someone who forged vast wealth from nothing. That’s more impressive than a medieval alchemist turning lead into gold. To be a king is one thing, but to be king by one’s own hand — like Conan the Barbarian — is legendary. Surely we are blessed such people walk among us.

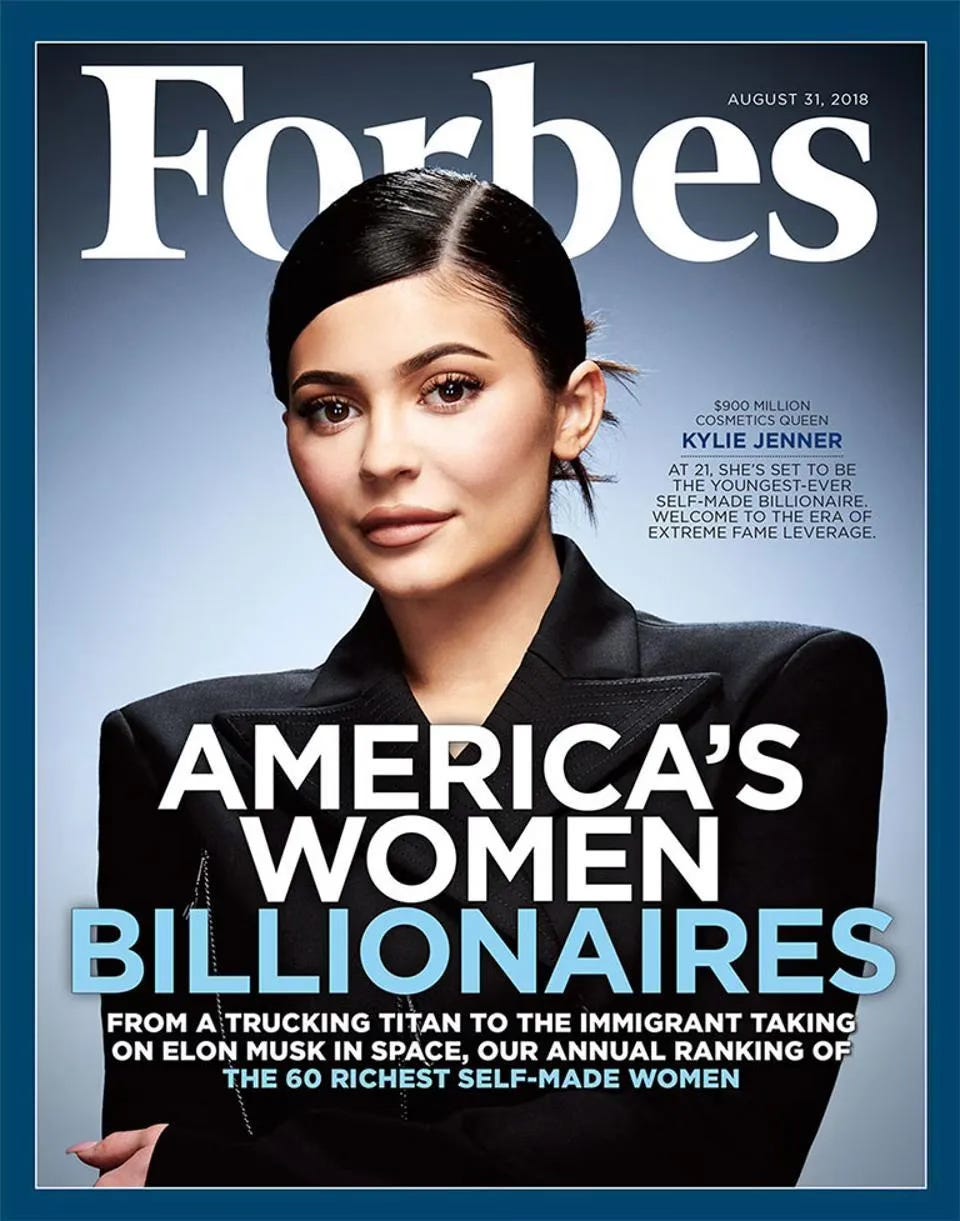

The “self-made” label promotes idolatry, the absurd apex of which was surely reached when Forbes ran a feature on “the sixty richest self-made women.”

The cover was adorned with the heroic visage of Kylie Jenner.

At the risk of belittling Kylie Jenner’s towering accomplishments, I must insist she is not remotely “self-made.” Not because her family bestowed on her a reality TV role she leveraged to make her fortune. Her biography has nothing to do with it.

No one is “self-made.”

Not Elon Musk. Not Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg.

Not Bill Gates or Warren Buffett.

Not Henry Ford.

No one. Ever. In any country. At any time in history. No rich person has ever been “self-made.”

Every fortune ever made is at least partly the product of networks and institutions — familial, social, educational, transportation, legal, political, security, health, etc. — that the person holding the fortune did not create. Or to put that more simply, every fortune ever made could not have come into being without other people.

In no real sense is any billionaire “self-made.”

If you worry I’m about to springboard this post into a “tax the rich” screed, let me assure you, no, I’m not. (If you hope I am, sorry.) It isn’t socialism to say no one is “self-made.” It is reality.

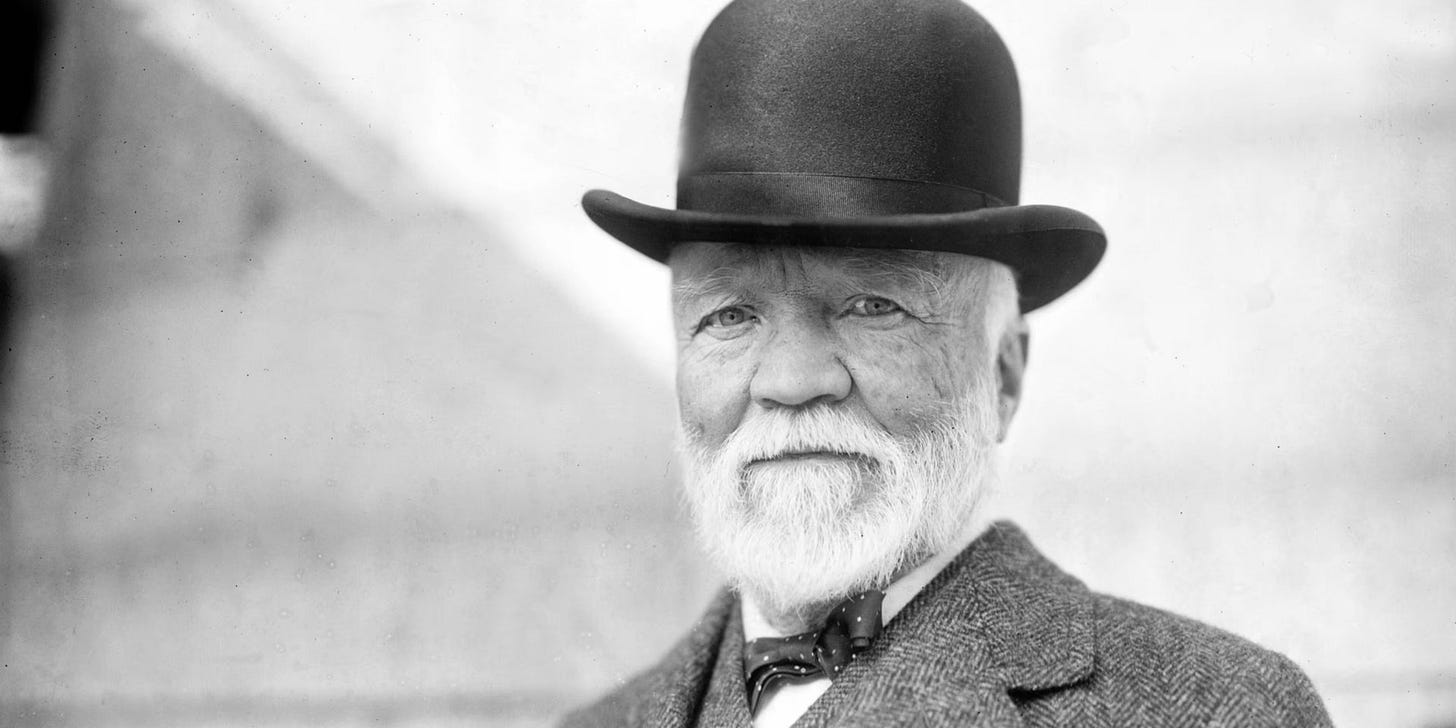

Andrew Carnegie — Scottish immigrant to America, the original robber baron, one of the towering billionaires (inflation-adjusted) of the Gilded Age — understood reality better than most.

Carnegie got his start in life not in a school but in a Pittsburgh cotton factory where the boy worked twelve hours a day, six days a week. In another factory, he got a job tending the steam engine in the basement, shovelling coal in stifling heat and filth. At 15, Carnegie got the break that changed his life. He became a telegraph messenger. With brutally hard work, constant self-directed study, and fierce determination — and more than a little ruthlessness — Carnegie steadily climbed the long ladder of America to its highest peak.

If anyone in history deserved to be called “self-made,” it was Andrew Carnegie. But Carnegie would have none of that. He knew that his fortune was the product of a vast industrial enterprise embedded in all the other institutions and networks that constitute society. He knew that he was a billionaire because countless others shovelled coal into steam engines. As a robber baron, he could be brutal. But he always knew in his bones where his money came from.

In 1889, Carnegie published The Gospel of Wealth, a short essay I wish every billionaire on the planet would read and seriously contemplate. You can find the full text here. It’s well worth your time, billionaire or no.

Three years ago, I wrote an essay quoting Carnegie at length, with extensive commentary and biographical detail, so I’ll simply note that Carnegie wouldn’t neatly fit in any political category we know today. On the one hand, he was a rock-ribbed capitalist who insisted capitalism makes everyone from the billionaires to the coal-shovelers better off — and any talk of socialism or communism was purest folly. But unlike some of our more vociferous billionaires today, Carnegie was capable of holding more than one thought in his head, and he frankly acknowledged that while capitalism lifted all boats, it also concentrated stupendous wealth in the hands of the few while leaving most to choke on coal dust. It was a moral conundrum.

How to resolve it? Not with fantasies of being “self-made.” Instead, Carnegie wrote, the billionaire should see himself as “but a trustee for the poor” because his wealth is not his alone. He is simply “entrusted for a season with a great part of the increased wealth of the community.” And because the billionaire’s wealth is not his alone, Carnegie argued, he has a duty to give that wealth away in whatever manner he thinks will best benefit the community.

Those who don’t are, in Carnegie’s eyes, moral monsters, the human equivalent of dragons who hoard wealth and breath their last on heaps of gold: “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced,” Carnegie famously concluded. Harsh words were not enough for such miscreants, however. Their wealth should largely be confiscated, Carnegie argued. “By taxing estates heavily at death the state marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire's unworthy life.”

Carnegie lived up to his words. Among the wide array of good works he funded in his lifetime were 2,509 Carnegie libraries in cities and towns around the world.

I wish an essay written by a robber baron 136 years ago were not relevant today. But The Gospel of Wealth is at least as important in the present as the day it was published. In fact, Andrew Carnegie’s perspective may be America’s only hope of pulling out of its spiral.

In 2020, the legendary political scientist Robert Putnam showed with a trove of data that since the 1960s the United States evolved in ways that make America in the present startlingly similar to the America of Carnegie’s era. To some, that may sound just fine. Donald Trump has repeatedly said the United States was at its richest in the Gilded Age, when there were tariffs, no income tax, and the government had so much money it didn’t know what to do with it. It’s a theme repeated by Howard Lutnick, Trump’s billionaire commerce secretary. (Is it true? See the postscript below.) But for anyone who knows that the term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain to suggest an era when a thin veneer of gold hid the corruption and rot beneath — that is, for anyone who knows anything about the real Gilded Age — Robert Putnam’s careful demonstration of parallels between that era and the present is frightening.

Huge and growing wealth disparities are only the most obvious parallel between the present and that distant past. The same is true of growing health disparities, as the rich live longer while life expectancy has slowed, stalled, or even reversed, for much of the rest. But most importantly, today’s America resembles Gilded Age America — in stark contrast with the America of the mid-20th century — in being a radically selfish, hyper-individualistic society.

Looking at the very broad trends across a host of indicators, Putnam sees what he calls the “I-We-I” cycle.

America in the late 19th century: a socially fragmented nation in which “get mine and devil take the hindmost” was the prevailing ethos.

American in the mid-20th century: a society with strong social fabric in which American individualism is balanced with a social ethos that we need each other.

America today: back to the “get mine and to hell with you” ethos.

As a result, trust levels in recent decades have been plunging and social capital is dissolving. Think of social capital as the bonds between people. It is as fundamental to the wellbeing of a society as the sort of capital Trump and Lutnick care about. Arguably, more so. And America is running out of it.

Putnam is careful to note he can’t disentangle cause-and-effect in such a complex puzzle. But one chronological sequence seems particularly important to me: The fragmentation since the 1960s mostly preceded the rise in wealth inequality. That suggests wealth inequality did less to dissolve social capital than some economically minded observers may think. It seems likelier that dissolving social capital promoted at least some of the policies — tax cuts for the rich, cuts for the poor — that spurred rising wealth inequality. That would make culture, not economics, the primary driver behind the move to a society in which a billionaire who published an updated version of Andrew Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth — urging billionaires to seem themselves as “trustees” of “community wealth” — would be condemned by at least half the country as a Communist. No doubt Trump would try to deport him.

It’s forgotten now but I think a major milestone came during the 2012 election campaign, when Barack Obama gave a speech about success and solidarity. Obama said business successes should be celebrated and rewarded, but it was important to remember that such successes don’t happen in isolation.

…if you've been successful, you didn't get there on your own. You didn't get there on your own. I'm always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something – there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there.

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you've got a business, you didn't build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn't get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.

The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together.

At almost any time in the 20th century, Obama’s speech would have been as controversial as a Hallmark greeting card. Democrat or Republican, it would have made no difference. Of course individual initiative matters. Of course the community around the individual matters. They’re both important. I’ve seen similar sentiments expressed by everyone from Ronald Reagan to Dwight Eisenhower. Similar sentiments were boilerplate for Herbert Hoover.

Yes, Herbert Hoover.

But by 2012, the Republican Party, in particular — the Democrats moved too, but not so much — had become a party of extreme individualism in which any suggestion that people need each other in order to accomplish things would make Republicans hiss “Marxist!” So the American right spent weeks hammering Obama as a dangerous collectivist, or even a secret Kenyan socialist, because he said something that would have made Herbert Hoover shrug.

But what comes around can also go around.

In the Gilded Age, as now, the dominant ethos of devil-take-the-hindmost created a violent, corrupt, fragmented, dangerously unstable society. That gave rise to the turn-of-the-century Progressive reform movement that shaped the more egalitarian, more honest, more stable — and more prosperous — America of the mid-20th century.

That’s why Putnam’s message is, despite the blizzard of grim numbers, ultimately hopeful. In the past, Putnam argues, America reformed itself and delivered a happier future. It can again.

Putnam makes his case in The Upswing. It was released in 2020 and I suspect the pandemic diverted the attention it would otherwise have received. It should be much better known than it is. I think it is one of the most important books of our era. It is also a brilliant use of history to illuminate the present and light the path to a better future. I hope to write something substantial about it in the coming months.

In the meantime, let’s do our bit for a better future by consigning the phrase “self-made billionaire” to the dustbin of history.

“Gangster isolationism” revisited

Look at Donald Trump’s statements about the world since the 1980s and it’s perfectly clear the man has always favoured a policy of what I have been calling “gangster isolationism” or “gangsterism” for years. “Gangsterism” means no permanent alliances and friendships, only the ruthless use of power to squeeze whatever America can from others as and when it wishes. It’s all about the shakedown.

I got a little pushback for that. Such extreme language, I was told. “TDS much?”

Well, we now have the better part of a year of Trump in office and the one word appearing in almost any fair account of his actions is “extortion.”

Over and over again. Foreign allies? Extortion. Universities? Extortion. Corporations? Extortion. Trump is like a baseball pitcher who can only throw fastballs.

I wish I could be embarrassed that I called Trump a gangster. But I don’t feel embarrassed. I feel prescient.

About that Golden Age

As noted above, Trump and Lutnick are big fans of the Gilded Age, which they have both called a “golden age,” perhaps because they don’t know what Mark Twain meant by calling the age “gilded.” (Hint: There’s lot of gold in Mar-a-Lago, but Mar-a-Lago isn’t “golden,” it’s “gilded.” The gold is only a veneer, an ostentatious fraud.) Call me cynical, but I don’t think their infatuation is the product of wide reading in history because there’s a simpler explanation: Rather, Trump has been a fan of tariffs since Madonna sang “Material Girl” because rent seeking is as natural to gangsters as the taste of gazelle is to lions. When he became president, and people started lining up to curry his favour, someone who paid attention in American History 101 told Trump that in the Gilded Age the federal government had no income taxes and funded itself largely with tariffs. So Trump became a Gilded Age fan. Which meant those who wanted Trump’s ear became Gilded Age fans. And now there’s a little industry of people who should know better talking up how wonderful the Gilded Age was.

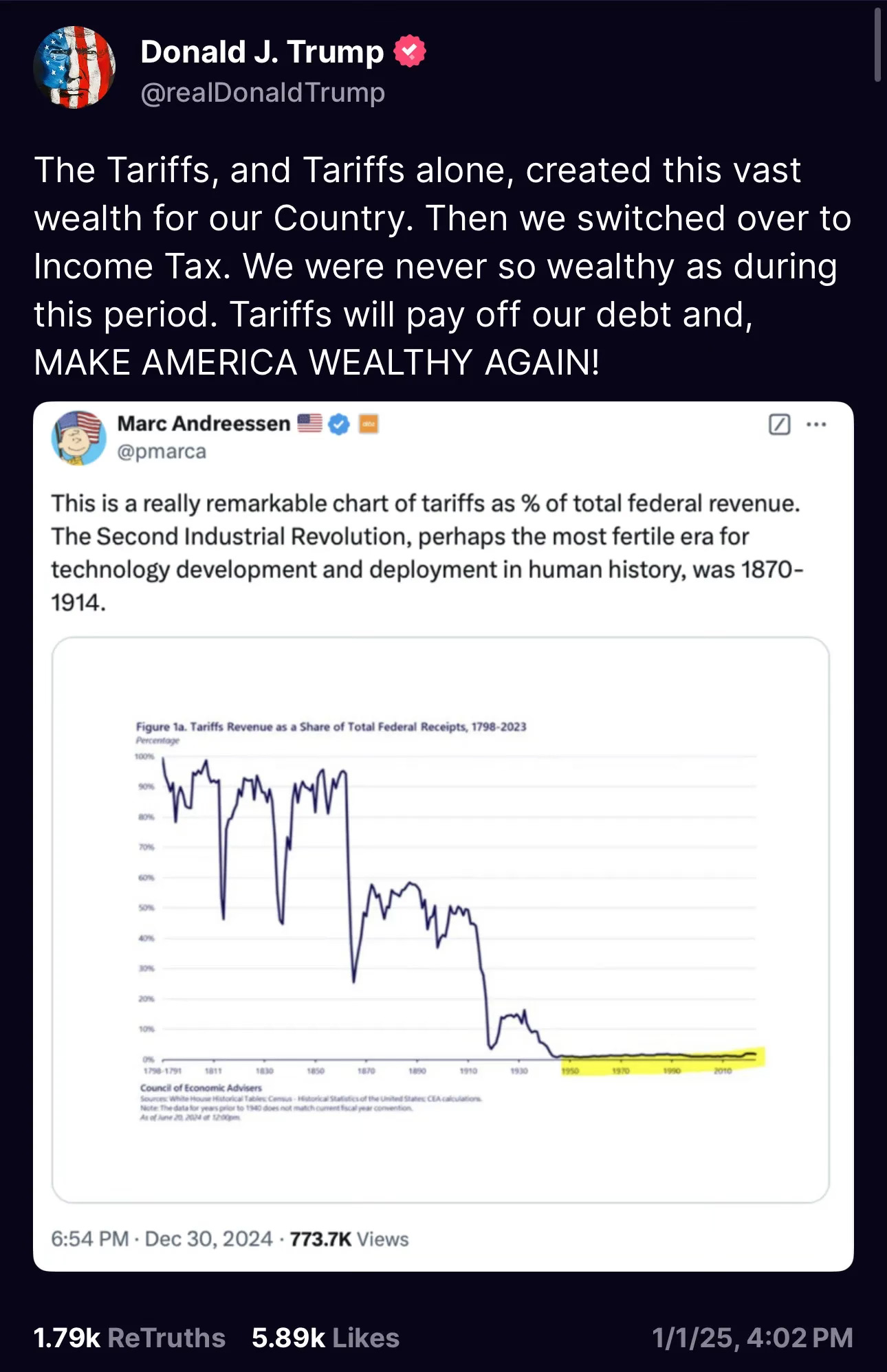

Check out the gem below. The first tweet is from Marc Andreesen, a major Silicon Valley VC, and now, thanks to backing Trump, a major voice in federal policy. Then Trump adds his gloss.

What Andreesen seems to want others to infer — while maintaining plausible deniability — is that federal tax policy in the era between 1870 and 1914 helped cause the explosive technology development and deployment. Which is bollocks, as anyone familiar with the technology of the era will know. But that’s sub-bollocks, as it were. Let’s stick to the chief bollocks.

Paul Krugman had a good short post about how this story is intended to make Americans forget that the mid-20th century, not the turn of the century, was the real golden age — for the simple reason that the mid-20th century was dominated by policies Trump hates, particularly high taxes on the rich. Talking up the Gilded Age is a way of promoting the replacement of progressive income taxes with regressive tariffs, which means shifting the tax burden from the rich to the middle-class and poor — and it doesn’t sound so sexy when you put it like that, does it? So, yeah, talk up the Gilded Age.

But dishonesty aside, two things drive me nuts about this talk.

First, the federal government then does not remotely resemble the federal government now.

There was no Social Security. No healthcare support of any kind. No FDA. No NASA. No FEMA. No FBI. No CIA or NSA. No… You get the idea. Go through the list of federal government agencies and departments and programs and you’ll discover that almost none of what exists now existed then. And the few that did exist then were a shadow of what they are today, in this vastly bigger, more complex world.

The US military is the best illustration. Trump loves his military. It’s the biggest, the best, the most wonderful. But the US military in the Gilded Age? It was not small. It was tiny. In the 1890s, before the Spanish-American War, the Army’s ranks numbered, at most, in the low tens of thousands; today’s New York Police Department has 36,000 uniformed personnel and another 19,000 civilian personnel. In 1891, the US Navy had 46 ships. Total. Of all types in all oceans. Forty-six.

So when Trumpians say that during the Gilded Age the federal government was largely funded with tariffs, they’re right. Technically. But they’re also trying to deceive you. Don’t let them.

The other thing that drives me nuts about talking up the Gilded Age is more fundamental.

It is true that the Gilded Age saw rapid growth and technological progress. (In the 1870s, it also brought a crash and a recession so severe it was known as “The Great Depression” until the 1930s depression displaced it. But, hey, details.) It was also a violent, scary era in which poverty so severe we can barely contemplate it today was commonplace.

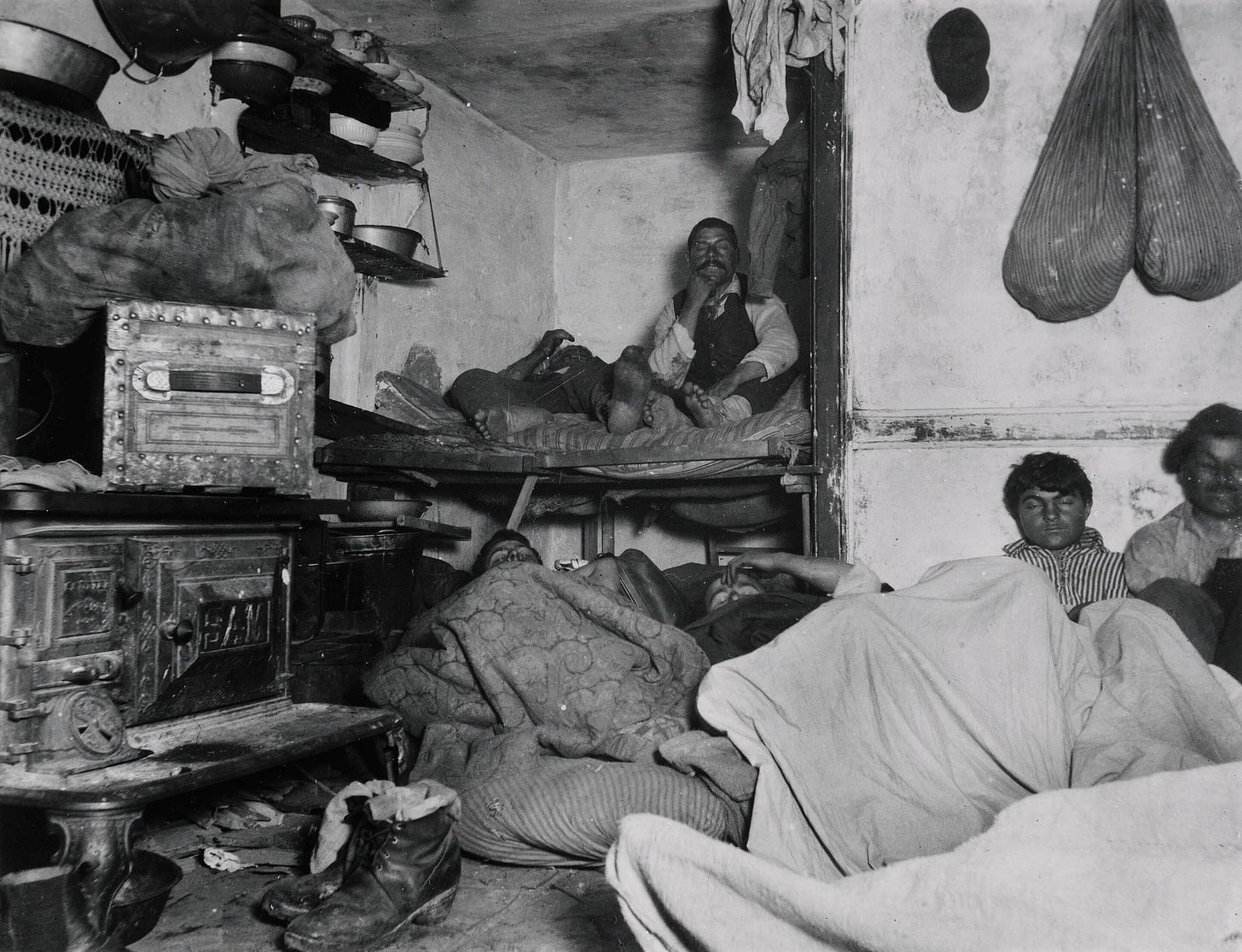

I could go on and on about this. I won’t. Instead, I’ll suggest you read How The Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis, the classic account of life in New York City’s tenements.

Riis was also one of the very first photojournalists and he took stunning images as he wandered the streets. A number can be found here.

Or just look at the image below.

This is what Donald Trump and Howard Lutnick call a “golden age.” This is what they aspire to bring America to.

There’s a Carnegie library in my neighbourhood: the Rosemount Library in Hintonburg, Ottawa. Its story is an interesting illustration of two types of billionaires.

When Hintonburg decided it should have a public library, “...thirty of Ottawa’s millionaires were approached for donations as it was hoped that the library might be erected with money donated by Ottawa’s wealthy citizens.’ (Ottawa Citizen, 1918)

Number of donations received: Zero.

Number of replies (even rejections) received to the donation request: Zero.

So, the mayor wrote to the Carnegie Foundation. Some thought this scandalous – a capital city shouldn’t have to appeal to a foreign benefactor in order to build a public library!

The Carnegie Foundation gave $15,000. The library was built, and is still much-loved and in constant use – one of the busiest public libraries in Ottawa, in fact.

There, in a nutshell, is the difference between the dragons and the custodians.

Thanks for this fascinating historical perspective, exactly what drew me to PastPresentFuture in the first place.

The City of Stratford (Ontario) accepted Carnegie’s donation on the condition that his name not be put over the door. How many of the current crop of narcissistic billionaires would accept that condition?