On Kahneman and Complexity

Reality is complicated. Our thinking should reflect that.

A couple of weeks ago, I started drafting a post that led off with Daniel Kahneman’s now-famous story of being a seven-year-old Jewish boy in Nazi-occupied Paris.

One day, playing with a friend, Kahneman stayed out past the Nazi-enforced curfew. When he realized how late it was, he turned his sweater inside-out to hide his gold Star of David and hurried home.

A man stopped him. A German. In a black uniform. Kahneman knew this man was SS, the people he had been taught to avoid above all others.

The man picked up the boy and hugged him. He took out his wallet and showed Kahneman a picture of his little boy. He gave Kahneman some money and sent him home.

“I remember the astonishment, the complexity of it,” Kahneman recalled in an interview with Steve Forbes. “That was telling you that life was very complicated.”

Daniel Kahneman died last week at the age of 90. His legacy is immense. He was, as he put it, the “grandfather” of behavioural economics — think economics but with a realistic model of what a human is — a role which won him a Nobel Prize. But Kahneman’s legacy is bigger than that. Kahneman and Tversky changed how we think about how people think, and if you change that, you change everything. You can see their influence all across the social sciences and much of the humanities.

But this is not a remembrance of Daniel Kahneman, whose endorsement of two of my books will forever be a professional highlight. There are many, lovely reflections on Kahneman as a man and scholar. I recommend Daniel Engber’s appreciation of Kahneman’s willingness to say those three simple words, “I was wrong.”

This post is about complexity.

Kahneman wasn’t unsettled by complexity. It intrigued him. Basic human decency from an SS officer? What a devilish contradiction. Fascinating! Among the ingredients required to become the insightful researcher he was, Kahneman’s comfort with complexity has to rank near the top.

That comfort also separated him from a goodly portion of the human race.

H.L. Mencken, that nasty old cynic, famously wrote that “for every complex problem there is a solution that is simple, clear, and wrong.” Simple and clear. That’s what most people want — which is why every marketer knows that simple and clear sells, whether you’re selling toothpaste or public policies or politicians. Simple and clear may not work, mind you. It may deliver disaster. But it definitely sells. Donald Trump has repeatedly said the war in Ukraine is so simple and clear he could settle it “in a day” and a large portion of the American population does not take that statement to be the grotesque hubris of a delusional narcissistic conman. They hear confidence and they find it reassuring. Because they are not fascinated by complexity. They are frightened by it. And they want someone to sweep it away — which Trump does at every rally.

I was reminded of all this by the release of a new study exploring the relationship between political knowledge and political extremism.

Among political scientists, it’s widely believed that knowledge and extremism have a positive correlation, so as you go toward the extremes of both left and right, you see knowledge rise. It’s not hard to imagine how that dynamic could come to be.

If you have no interest whatsoever in politics, you are likely to define yourself — if pressed to define yourself in political terms — as being somewhere “in the middle.” That’s not a centrist by conviction. It’s a centrist by default. Something similar happens when people are asked to choose the probability of some event or answer or whatever: If you graph their answers across the range of probabilities, from 0 to 100, you often get a spike at exactly 50% — because people treat “smack in the middle” as meaning “I dunno.” It is the numeric equivalent of a shrug.

A centrist-by-default is very unlikely to possess much political knowledge. They’re just not interested. And if their lack of interest doesn’t change, neither will their knowledge. So people who are ignorant and apathetic are likely to be found clustered at the centre.

The dynamic is quite different for someone with an interest in politics.

If you are interested, you probably have been collecting political information and forming political judgements. You are not likely to shrug and say “I’m in the middle, I guess.” You are likely to give a more considered judgement which will put you on the right or the left, at least to some degree.

You will also continue to seek out new political information, but having drawn a conclusion about which side is more correct, and having labelled yourself accordingly, that information processing isn’t likely to be unbiased. You will tend to go looking for information that supports your existing views, whether right- or left-wing, and you will tend to accept such information uncritically. Simultaneously, you will not think to go looking for contrary information and if you happen to bump into some you will subject it to far more skepticism. This is Confirmation Bias 101. The net result is predictable: Your modestly left views, or modestly right views, will become more left or more right.

If you continue to hoover up information in biased fashion — and you probably will — you will be nudged further along the spectrum. You’re now in a feedback loop which steadily inches you away from the centre. If this loop continues, you will gradually become both more knowledgable and more extreme. Hence, political knowledge and political extremism increase together.

But the four co-authors of an important new paper argue that earlier papers which claimed to find this pattern were flawed in various ways. They used small datasets. They only surveyed Americans. That sort of thing. So the authors of The Association Between Political Orientation and Political Knowledge in 45 Nations attempted to do better with a sweeping study that drew on international surveys.

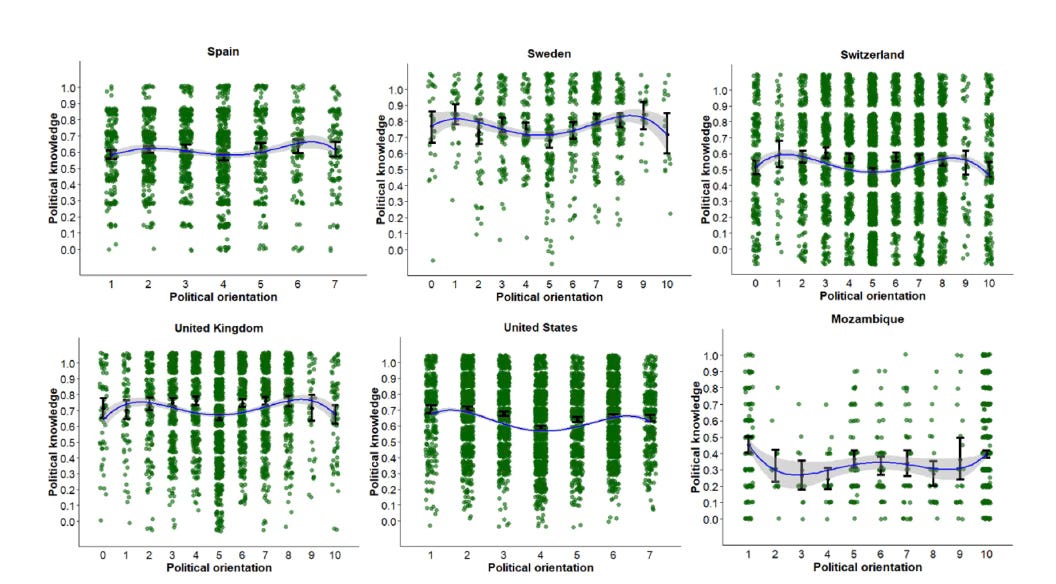

The researchers “found no evidence that people at the political extremes are the most knowledgeable about politics.” Instead, they found — to the delight of complexity-lovers — patterns that varied by geography and culture.

The most common of these patterns was one in which political knowledge was low in the centre and at left and right extremes, while the highest levels of political knowledge were found among those at the moderate right and the moderate left. This pattern dominated Western countries.

A sample:

This paper got me thinking about Superforecasting and conversations I’ve had with my co-author Phil Tetlock.

If you’ve read Superforecasting, you’ll know a big theme is the value of seeking out various perspectives and synthesizing them into a single judgement. We used the metaphor of a dragonfly’s eye to illustrate.

You can see how the orbs are composed of thousands of tiny lenses. (Technically, they’re not lenses. But non-entomologists would call them lenses.) Each of those lenses has a slightly different position than all the other lenses. So each has a unique perspective. By synthesizing thousands of these unique perspectives, the dragonfly’s brain creates an astonishingly broad and accurate picture of reality — which allows dragonflies to pluck mosquitoes out of the air at high speed.

Humans can do something similar.

Seek out other perspectives. Don’t be deterred by difference. Relish it. If someone believes precisely what you believe, you learn nothing from them. But if someone has a very different way of seeing a situation, and has come to very different conclusions, that’s someone worth listening to. Of course, that doesn’t mean you blindly accept contrary views. You can’t. They’re contrary to your own, and, often, each other. You need to synthesize them with your own, and with the other views you collect. That requires constant critical analysis of what you’re hearing, of the quality of the reasoning, of the strength of the evidence it rests on. And a relentless struggle to understand how it squares with other views.

None of this comes naturally or easily. But it’s worth the effort. As we showed in Superforecasting, this sort of “actively open-minded” thinking produces demonstrably better judgements. Just as the dragonfly is better able to spot and catch mosquitoes, the actively open-minded are better able to discern the present and forecast the future.

But something else happens when we are actively open-minded.

We learn a lot, of course. An actively open-minded thinker is likely to be a well-informed thinker. And what we learn is likely to be very complex. We are seeking out contrary perspectives, after all. That means we get lots of contradiction. Some of what we learn points in one direction. Some in another. It’s all very complicated.

What happens when we synthesize all those different views pointing in different directions? It’s likely — not certain, not universal, but likely — that we will land somewhere closer to the middle of the range of views than the extremes.

This is why I think, as a general proposition, that actively open-minded (and politically interested) thinkers will tend to be knowledgeable about politics. And they will tend to fall closer to the middle of the political spectrum rather than the extremes. Those at the extremes, conversely, will tend to possess less knowledge because less knowledge means what you do know is more likely to line up in one direction — which makes it easier to draw extreme conclusions. Hence the pattern discovered by researchers in the paper above is precisely what I would have predicted.

So congratulations, me.

Now, I won’t blame you if you think this is all Dan Gardner’s elaborate explanation for why the relatively centrist political views of Dan Gardner are superior to those of foolish extremists. I cannot deny the possibility that the hidden depths of my unconscious mind have guided me to a self-pleasing conclusion in a sort of meta-confirmation bias. But I think this argument makes sense. And that’s the best I can do.

I also have to put a big asterisk on my claim. It does not follow that political centrism, or moderation, is everywhere and always the superior position. Context is all. The Missouri Compromise had moderation right in its name but it was still wrong — while adamant abolitionists, the “extremists” of their era, were right.

Caveats aside, I do believe strongly — as in, willing to die on this hill — that there is at least some scrap of value in almost every perspective. People who dismiss whole political movements, or concepts, or thinkers on the assumption that literally everything within them is utterly and completely valueless are deeply misguided. You know the sort of person I mean. They’re the people who think there is no point reading one word of critical race theory or DEI policy because it’s all hogwash or worse. Or they’re the sort of people who are enraged when The New York Times interviews and tries to understand Trump voters. This attitude could not be more mistaken. There is value, however modest, to be found in almost every view, and if we we assiduously collect these bits and pieces of value, we will get more knowledgeable, our thinking will get more complex, and we will see reality a little more clearly. And our thinking, more often than not, will avoid the extremes.

Do this often enough, make it habitual, and when you encounter something as astonishing as a Nazi behaving humanely, you will not seek to impose order on your unruly perceptions by denying some part of what you see. You will accept the complexity. And see reality a little more clearly.

You may even embrace the complexity and find it as fascinating as Daniel Kahneman did. And that’s a strong hint you’re moving in the right direction.

Your asterisk condition is likely more important than it might appear at first. Overall views may be dominated by one issue of strong emotional value where compromise is impossible or extremely difficult. Abortion as an issue comes to mind. Or calls to the centre are extremely difficult to achieve in what are seen as binary decisions. Don’t recall where I read this example but in asking people whether they want pizza or a hamburger, very few would see the ideal result as a pizzaburger. So, if being on Team Pizza correlates with a set of beliefs and that this represents a crucial issue for me, I will not easily compromise on other issues, even if ultimately there should be no linkage.

Also, it is probably true that most of us overestimate our knowledge and understanding of issues. I seem to recall experiments showing that our estimates of our knowledge levels on an issue fall once we are asked to explain a process or an issue. Reflective as well, I suppose, of how few of us have an actively-open mind.

Linked to that is the probability that we close our minds once we have analyzed an issue with complexity because we don’t want to go through that process again. I remember being frustrated years ago trying to decide what TV cable/internet package to buy. None of the offerings ever allowed me to purchase the perfect mix that suited my needs. To get that mix cost became exorbitant and the default options always required purchasing things that were totally unnecessary. However, once the decision was made no amount of argument seemed likely to shift me off that position because I did not want to go through that process again and had no confidence that a better option was really available.

Personally, I don't find the Paris Nazi story at all extraordinary. Nazis were ordinary people in every respect, except for their hatred of Jews. You see the same thing in human nature the world over, throughout history. People who got along perfectly well and even intermarried in the former Yugoslavia suddenly turned on each other with an unimaginable ferocity and barbarism. Queers for Palestine defend atrocities against innocent Israelis that would have had themselves as targets had they been at that time and place. Civilization is a thin veneer over humanity's darker side, always ready to bust out - usually in very limited, focused directions (because it is too hard to hate everyone everywhere and live a normal life).

The mistake people make is to think that all bad things cluster together, and all good things cluster together, creating a binary. Good and bad impulses intertwine in human nature seemlessly.