People > Technology

Introducing a new series about the history of technology

Ezra Klein recently interviewed Jonathan Haidt, an enormously accomplished psychologist. (I routinely use his famous elephant-and-rider metaphor in lectures.) But you probably know Haidt best as a critic of smart phones and social media, technologies he blames for a host of ills — from dissolving social bonds to suicide — plaguing the generation that grew up with iPads and iPhones.

Haidt has both critics and supporters (I lean more to the latter) but I won’t judge his case here. It’s a complex debate and we’re a long way from settling it.

Instead, I want to focus on one particular observation of Haidt’s in that interview with Ezra Klein. It is essential for this issue, but it also applies much more broadly. In fact, I think it underscores a critical point we all need to understand in this era of sweeping technological change.

It came shortly after Klein mentioned a new regulation in Australia that requires social media and other platforms to block minors by deploying age-verification systems more robust than the “please lie to enter website” checks that exist now. Haidt helped inspire the policy. He strongly supports it. And he says that in country after country, support for the policy spans the political spectrum.

But two stumbling blocks remain.

One is technical: Quick, easy, accurate age verification systems do not yet exist.

The other stumbling block is human. It’s the real problem. It’s the one that truly matters.

Haidt explains:

The one real obstacle I have faced, once I put the book out — parents have loved it and are embracing it. Teachers are embracing it. The main objection I’ve gotten is resignation.

It’s just people saying: Ugh, what are you going to do? The technology is here to stay. Kids are going to have to use it when they’re adults — might as well learn when they’re kids. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.

But actually, we can. And we’re doing it. So I really want to make the point that we don’t have easy age verification now, but if we incentivize it, we’ll have it within a year.

Scott Galloway, my colleague at New York University, gives the example of how the social media companies, this industry, have put a lot of research and money into advertising. And so they figured out a way that, when you click a link anywhere on the internet and then the page loads — in between that time, there has been an auction among thousands of companies for the right to show you this particular ad. This is a miracle of technical innovation. And they did that because there was money in it.

And now the question is: Do you think maybe they could figure out if somebody is under 16 or over 16?

Tech companies have immense incentives to track highly specific data about each and every one of us — because advertisers will pay a lot of money to know that I’m a 57-year-old man who buys lots of non-fiction books and gardening products. As a result, the systems for doing that analysis and advertising are fantastically sophisticated and effective (and tech companies know a hell of a lot more about me than the preceding.)

But tech companies have no incentives — in fact, they have big disincentives — to figure out how to quickly, easily, and accurately determine if the person trying to access social media is an adult. Hence, age-verification systems are a joke.

It’s not hard for a government to create incentives for tech companies to get serious about age verification. Regulate it. Attach stiff fines for non-compliance. Let the free market work its magic. Done.

Of course the tech companies will moan that it’s impossible, but put their immense profits at stake and you can be sure they’ll deliver the impossible a couple of weeks after they stop complaining about how impossible it is. This is an old story in the history of regulation. As a journalist, I witnessed an example years ago, when the government of Canada ordered cigarette companies to feature full-colour photos of blackened lungs on their packages. It’s impossible, the companies insisted. The printers can’t do it. Shortly after the regulations passed, the printers did the impossible. Imagine that.

Why, then, does Haidt encounter so many people “resigned” to the technological status quo? Why do so many people think that once a technology appears, we can’t control it, shape it, make of it what we choose?

Why do so many people think we must adapt to the technology, and not the other way around?

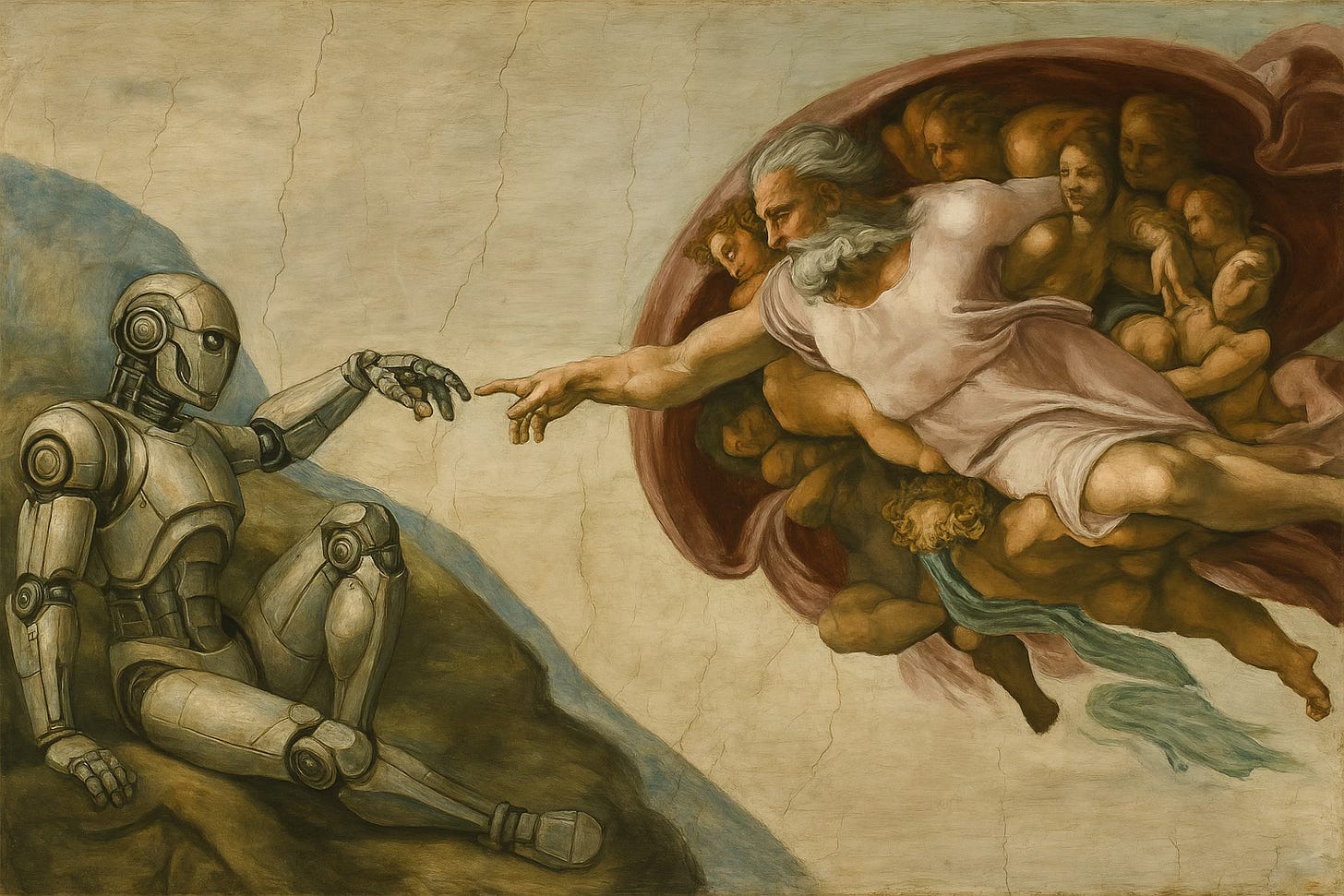

That’s a complex question with a complex answer. But the core of that answer, I believe, is technological determinism.

Don’t be put off by the number of syllables. “Technological determinism” is simply the idea that technology is in the driver’s seat.

In this view, a technology becomes an independent force in society the moment it is invented. Will it be widely adopted? The technology’s own properties will determine that. How will people use it? How they will not use it? What social effects will it have? The technology determines all that. People can’t change the outcome. We can only adapt to it.

Resistance is futile, as the Borg say.

If you’ve never explicitly thought about technology this way, or even heard the term “technological determinism,” that’s only because these theoretical debates seldom emerge in these terms from academic books and university seminars into newspapers and blogs. Yet this way of thinking about technology is all around us, at least implicitly.

“A surprising number of people, including many scholars,” writes renowned historian of technology David Nye, “speak and write about technologies as though they were deterministic.”

Some do that for reasons of self-interest. If the widespread adoption of a technology is “inevitable,” you’d better buy it and use it before your competitors do, so technological determinism can be good marketing. It can also be good politics. If a technology will “inevitably” be used certain ways, government shouldn’t interfere. Or it should fund development. Or give special assistance, like legalizing copyright violations — so your country doesn’t fall behind.

But more often, people who implicitly talk about technology this way aren’t so self-interested. They’re journalists, politicians, bloggers and others in the public forum who stumble into the trap of technological determinism without ever realizing it. They say a technology will do this and that, or it won’t do the other. As if the technology decides what the technology will be and do. As if the technology decides how the technology will change our work and our lives.

“A thousand habits of thought, repeated in the press and in popular speech, encourage us in the delusion that technology has a will of its own and shapes us to its ends,” writes David Nye.

Like Nye, most historians who study the invention, development, and diffusion of technology think that’s very wrong.

I think it’s worse than wrong. It’s dangerous.

If we believe technology is in the driver’s seat, and the technology is taking us somewhere we don’t want to go, what can we do? Nothing, really. We must resign ourselves to it, like those parents resigning themselves to smart phones as a fixture of childhood. “What are you going to do?” they sigh. “You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.” Resistance is futile.

That’s why technological determinism is worse than wrong. It encourages us to cede control of our lives and societies, to be passive, to let change happen to us. it encourages us to treat objects as subjects — and reduce ourselves from subjects to objects.

Technological determinism is fundamentally dehumanizing.

The opposite of technological determinism is “social constructivism.”

Along with David Nye and most historians of technology, I believe social constructivism provides a much more accurate picture of reality.

It also happens to be empowering.

“Machines don’t just keep coming,” writes historian Jill Lepore. “They are funded, invented, built, sold, bought, and used by people who could just as easily not fund, invent, build, sell, buy, and use them. Machines don’t drive history; people do.”

People make choices that determine what technology becomes. People determine technology, not the other way around.

Or to put that even more bluntly:

People > Technology

Of course I must put a big asterisk on that. I am simplifying greatly. This is a huge, complex subject with lots of caveats and contradictions. But I’ll save all that for down the road.

My purpose today is simply to make …

Thrilling drumroll….

… the following announcement.

More thrilling drumroll…

For the foreseeable future, I’m going to research and write PastPresentFuture full time. And yes, the history of technology will play a big part in the new PastPresentFuture.

This is a big change for me.

For many years, my work has been writing books and giving talks about my books. This newsletter, which I started in 2022, has only ever been a hobby. I write what I want when I want. Quite self-indulgent. But now I want to get serious with it.

What am I going to write about? Some of it will remain as it is.

Yes, I’m still going to write about Donald Trump, although I will do so less often than I have in recent months, if only to preserve my sanity. But I can’t ignore the whole mishegoss. The world is undergoing seismic convulsions the like of which we seldom see (fortunately). As a student of history it is fascinating. I also think historical perspective is essential to understanding what’s happening in the news, and the news media is terrible at providing that. So I’ll stay on that.

History, memory, and commemoration are lifelong obsessions of mine, as longtime readers will know. They’ll make appearances.

Psychology and decision-making are core to my work, and they’ll get lots of airtime here. In particular, I have a new book that will be released in October (more on that in another post). Its theme is trust: How it is won and lost. Few issues matter more today, at every level, from neighbourhoods to corporations to nations. I’ll have lots more to say about that next fall.

Then there’s the big, new addition: the history of technology and what it tells us about society and technology today.

With the history of technology, I’m going to try something I’ve never done before.

Longtime readers will know I’ve been researching a book on the history of technology for six or seven years now. And I’ve had a contract with Crown (a division of Penguin Random House) to write that book since 2023.

The frustrating part of writing a book is that you can’t simply share interesting content as you find it. The Internet is full of content-churners. They’re thieves, basically, constantly ripping off whatever they think can boost their numbers. Nuggets of information. Amazing stories. Publish them on the Internet and there’s a good chance that by the time your book appears your fascinating discoveries are stale beer. So I have heaps of research I don’t dare publish here.

Is there some way to square that circle? I think there is.

I’m mostly not going to share the subjects and material I already know well. Instead, as I explore technologies I’m less familiar with, I’ll write about what I find (while withholding anything with clickbait potential, unfortunately.) PastPresentFuture has developed a wonderful audience of thoughtful regulars who often comment and share thoughts, so I’m hoping that as I root around in these histories, others will, too. Or will at least share thoughts and suggestions. In this way, we can learn and develop ideas together. And, over several years, help shape a book.

Now, if you were a cynic, you may say this sounds rather Tom-Sawyer-gets-the-other-kids-to-paint-the-fence. But you’re not a cynic. So I’m sure you see this as a writer of advancing years who has maintained sufficient mental flexibility that he wants to experiment with new technologies and new models of work and cooperation. Which is admirable. Indeed, it is something you want to support.

At least I hope that’s what you think.

That’s because I am not independently wealthy, much to my dismay, so making this my full-time gig means I have to make more money doing it. And that means I’m going to have to start putting up paywalls and pleading with people to take a paid subscription.

I know…

And I agree! I hate the proliferation of subscriptions for everything. It costs too much. It’s hard to keep track of. And it risks turning public discourse into an endless sales pitch.

I promise I’ll minimize the paywalls various ways. And minimize the sales pitches. But I can’t dispense with them entirely. Sorry. Don’t hate the player, hate the game.

And so I come to the close. Which is, naturally, a sales pitch.

Hundreds of people are already paying subscribers of PastPresentFuture, which is genuinely amazing considering I’ve always made my writing free for all. But now I need to bump up that number. If you like my writing here, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you like my books, you can help make more of them by becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for your consideration. And more importantly, thanks for reading.

I’m looking forward to learning more about your book on trust. Before the Trump calamity came to dominate the Canadian election I thought that one of the main ballot questions should be “how will you restore and enhance societal trust?”

It is still an important question, perhaps even more important, as Canadians stand up and together in challenging times.

You touched obliquely on a couple of my concerns around AI. The output of LLM AI is non-deterministic and you can't trust it's true. And yet its use is pervasive and I expect more than few people just believe it. When in history has a new (untrustworthy?) technology been adopted by a billion people within 3 years of its launch? The intersection of trust, truth, technology, and politics is a fascinating space. As a technologist for over 40 years I'm looking forward to peeking behind the paywall!