I’ve been spending considerable time going through American books, newspapers, and magazines from the years between, roughly, 1900 to 1935. The other day, I came across something that nearly knocked me off my chair. And it got me thinking about the nature of evidence — both historical and other kinds.

I was reading an obscure book. A really obscure book. It is a volume called Education on the Air, “the fifth yearbook of the Institute for Education by Radio,” a collection of conference papers written by academics who studied how to advance education using the amazing new technology of radio. It was published by Ohio State University in 1934.

It’s mostly as dull as it is obscure. But then I got to an essay entitled, “Where Is American Radio Heading?” It discussed the government’s regulation of radio, and the actions of the licensing authority, and concluded both needed to change but were not. Then came this:

On the whole, broadcasting is a purely private enterprise for private gain. The tendency of the licensing author, whether or not as deliberate policy, has been to crystallize the status quo, and you all know the darky’s definition of status quo: “Rastus, status quo am de Latin words fo’ de mess we’s in!”

If you’re not familiar with antique racism, I should explain that “Rastus” was a name commonly used by American whites for a generic black man who is amusingly ignorant. (In fact, the name was almost never used by black men. “Rastus” was the name given to a black character in the original Uncle Remus book, which was enormously popular among whites.) In the minstrel shows that were a major part of white culture in the late-19th century, white men would dress up in black face, grin, guffaw, and say silly things in exaggerated black vernacular. The characters in these shows were often named “Rastus.”

So what I was reading was an academic, at an academic conference in 1934, performing an old-time minstrel routine at the podium.

In a sense, I shouldn’t have found this so shocking. After all, the most popular program on radio at the time was Amos ‘n Andy, which featured two white actors pretending to be black and cracking jokes in exaggerated black vernacular — a somewhat toned-down version of the old minstrel shows, in other words.

But the man who delivered this paper was Levering Tyson. He had a PhD from Columbia University, had been an assistant to the president of Columbia, and was one of the first to advocate using the new technology for education. With the support of AT&T, and funding from Carnegie and Rockefeller foundations, he produced some of the first educational programs ever broadcast. Tyson later became president of Muhlenberg College, a private liberal arts university, and chancellor of the Free University of Strasbourg. He was the epitome of a thinker dedicated to the elevation of the public mind — and he performed a minstrel routine at an academic conference.

That context made it stunning. But more than that, it was stunning because I’ve seldom run into it’s like before. It was stunning because it is rare: I have combed through a huge amount of material from that era and there just isn’t that much explicit racism. Which is itself remarkable. Astonishing, really.

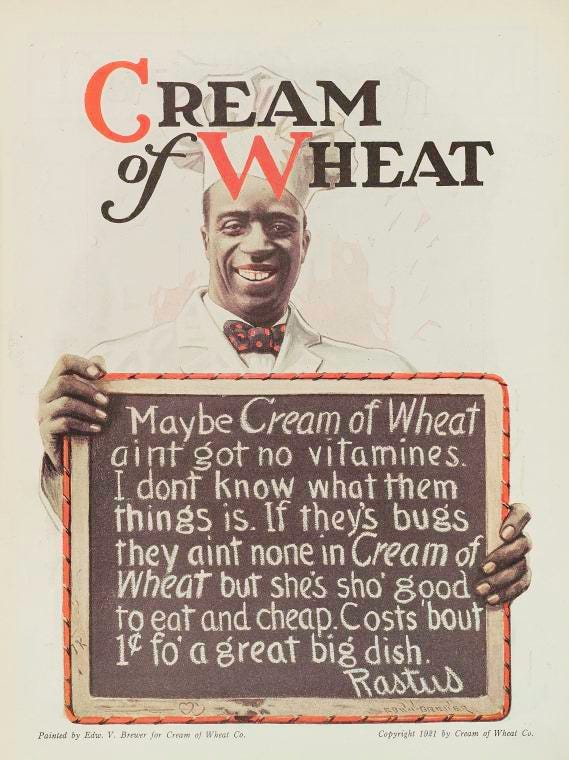

After all, this this was an era when ads and entertainment — like Amos ‘n Andy — were flagrantly racist.

In these years, the Ku Klux Klan was a major political force capable of drawing 30,000 members to a march in Washington DC. Scientific racism was even more mainstream, while writers like Lothrop Stoddard — an American who helped inform Nazi thinking — were respectable voices in cultured salons and halls of power.

Society was absolutely steeped in racism.

So how is it possible for this era to be profoundly racist and yet overt racism in the media was rare? This is where the nature of evidence comes in.

In all the material I went through, there’s something aside from overt racism missing: There are almost no black people. They’re neither the authors nor the subjects of the writing. They’re seldom mentioned even in passing. They’re just not there.

Even in popular histories that purport to survey the whole American experience — books like Our Times by Mark Sullivan and Only Yesterday by Frederick Lewis Allen — you would scarcely know blacks existed. And yet, at the time, black people were about 11% of the American population.

To give you a better sense of how bizarre this absence is, consider that, in 1921 — smack in the middle of the years Sullivan and Allen were writing about — white mobs rampaged through black neighbourhoods in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The death toll is unclear but it may have been in the hundreds. Thirty-five square blocks of the city were destroyed. Tens of thousands of blacks were left homeless. And yet, the word “Tulsa” doesn’t appear in Only Yesterday or the six thick volumes of Our Times. And I’ve never come across a reference to the massacre in all the time I’ve spent going through archives of the era.

Ads and light entertainment like Amos ‘n Andy may have been racist but they at least acknowledged that black people existed. In the books, magazines, and newspapers that served the white population — basically all the media outside of black communities — that was unusual. It was one thing to see black people as a source of amusement. It was quite another to think about them when it came to serious matters.

And that explains why overt racism could be rare in a time of extreme racism: The racism of the era primarily manifested itself in disregard and wilful blindness. For that reason, the most probative evidence is not the prevalence of racist jokes and the like. It is what’s not there.

This can be broadened to all of history. And beyond.

Like the dog that didn’t bark in the Sherlock Holmes story, what didn’t happen, what isn’t recorded, what’s not there, is often what is most revealing.

I bet that women are disproportionately missing too. And indigenous folk and Spanish speakers. If it didn't happen to, or concern, white men, it didn't happen.

Another quibble - 35 SQUARE blocks? Was this a 5 block by 7 block area that was approximately square? Or was it a square that was 35 blocks on a side? Or are you just quoting a sloppy account? Bring on the square acres.

Excellent post. The absence maintained the disenfranchised condition. When Barack Obama sought the Democratic nomination that set of a counter reformation. Anyone for a cuppa Woodrow Wilson?