Reason to Hope

Slow, incremental progress is powerful. And easy to overlook.

A few weeks ago, I went for a long hike with my elder son in Frontenac Provincial Park, an impressive swathe of wilderness in eastern Ontario. The trees were covered in a spray of frost, the ground dusted with snow, and ice crept outward from the shores of the small lakes that speckle the granite landscape of the Canadian Shield. An early morning fog lifted and the day became silver and silent. Over six hours and 15 kilometres, we didn’t see another human.

Rounding a lake deep in the park, we heard the unmistakable call of trumpeter swans and spotted a flight of six spiralling down for a landing. It was spectacular. Trumpeters are enormous birds, the biggest of all the swans, with adults weighing as much as 30 pounds (13.6 kg). Their wingspans can reach ten feet (3 m). And trumpeters are a pure, dazzling white that commands attention for miles around. When a flight of trumpeters comes in for a landing, horns blaring, the whole forest stops to watch.

But that moment was more than a delightful experience for my son and me. It was also a demonstration of how we miss what is going right in the world.

Trumpeters blanketed much of North America until firearms arrived and the swans were slaughtered relentlessly, as much for their plumage and skins as their meat. By the 1930s, trumpeters had effectively been wiped out across most of North America. Fewer than a hundred survived in the remote regions like Yellowstone Park. Extinction seemed certain.

In 1935, a tiny refuge in Montana was created to protect the few survivors. In the 1950s, a new population of trumpeters was discovered in a remote corner of Alaska, providing invaluable genetic diversity for breeding programs. In the decades that followed, the swan was protected by legislation and programs nurturing the population sprouted across the United States and Canada.

In 1968, the year I was born, there were an estimated 3,700 trumpeters in all of North America. By 2015, there were 63,000. And their numbers keep climbing. Until recently, we never saw trumpeters at my cottage, not far from Frontenac Park. Then came the occasional sighting. Now spotting trumpeters is almost common, or would be if it didn’t feel wrong to call something so spectacular “common.”

Every single sighting is proof that progress is possible.

At least that’s how I experience it. But does everyone feel the same surge of optimism when they spot one of those glorious swans? Probably not.

Certainly, anyone lucky enough to see trumpeters will be thrilled by the sight, but you can only see those birds as proof that progress is possible if you know the history. Do most people know that history? If they’re birders, sure. Same for conservationists. I know it thanks to my dad, who was a wildlife biologist, and my mum, who long ago worked for Harry Lumsden, a legendary conservationist who did much to restore the trumpeter.

But most people? They have no reason to know the history. And the growth in the population of trumpeters, however impressive it looks on a graph, is only incremental change spread across decades. That sort of change never makes headlines in the news because it never delivers a day or two when something significantly changes. And it is that sort of abrupt change — what’s different today than yesterday — that is effectively how we define “news.” As a result, despite the almost tectonic power of slow, incremental change to transform the world, such change may seldom or never be mentioned in daily news. Or public discourse.

The most extreme illustration of this dynamic is improved life expectancy. Nothing could be more important. When longevity inches up year after year, decade after decade, it utterly transforms human lives and societies. And that’s what has happened for most of the last two centuries in the developed world (and, increasingly, most other places in the world.) In fact, you could argue there is no bigger story in those two centuries than the enormous growth in life expectancy. But don’t look for it in the news. Slow, incremental improvement is all but invisible to journalists covering daily news.

The problem isn’t journalists, please note. It’s a human thing. If you spend decades living at a lakeside in eastern Ontario, but you’re not a birder, and you don’t know the history of trumpeter swans, you may notice when you see a trumpeter for the first time. But will you even recognize this is a first? Will you understand the significance? Probably not. You’ll only have a sense it’s unusual. And as you see trumpeters with increasing frequency over the years and decades that sense will fade. What will replace it? A sense that something important is slowly and steadily changing for the better? Almost certainly not. Seeing the swans will become normal. Baseline. Ordinary. It will only be a matter of time before you forget there was ever a time without swans. Having swans at the lake will simply be the way it has always been.

Human beings are not intuitive statisticians.

On top of this lies what psychologists call “negativity bias,” which is a tendency to give greater attention and memory to bad news over good: A species declared extinct commands attention — and headlines — in a way that a species slowly brought back from the brink never will. For most people in eastern North America, wild turkeys are a very common sight at roadsides or pecking away in farm fields. Their populations are measured in the millions. But wild turkeys, like trumpeter swans, were almost hunted to extinction by the early 20th century. If they had been wiped out, you can be sure most people would know that fact, just as they know about the extinction of the passenger pigeon. But instead, thanks to determined conservation efforts, turkeys had such a miraculous recovery that seeing them now elicits shrugs from people who have never heard the story of their a miraculous recovery.

This asymmetry can easily produce an excessively bleak perception of reality. And that’s why stories like the trumpeter are so important.

They tell us that we can do better, that even at the brink it is possible, with awareness and determination, to recover. Every single trumpeter swan is reason to hope.

Steven Pinker has been banging this drum for years, so I would be remiss not to mention his work, particularly the magisterial compendium of progress, Better Angels. Or this recent essay. Of you’d like to explore for yourself, spend some time on the website of Our World In Data, which has a huge array of interactive charts about the state of the world.

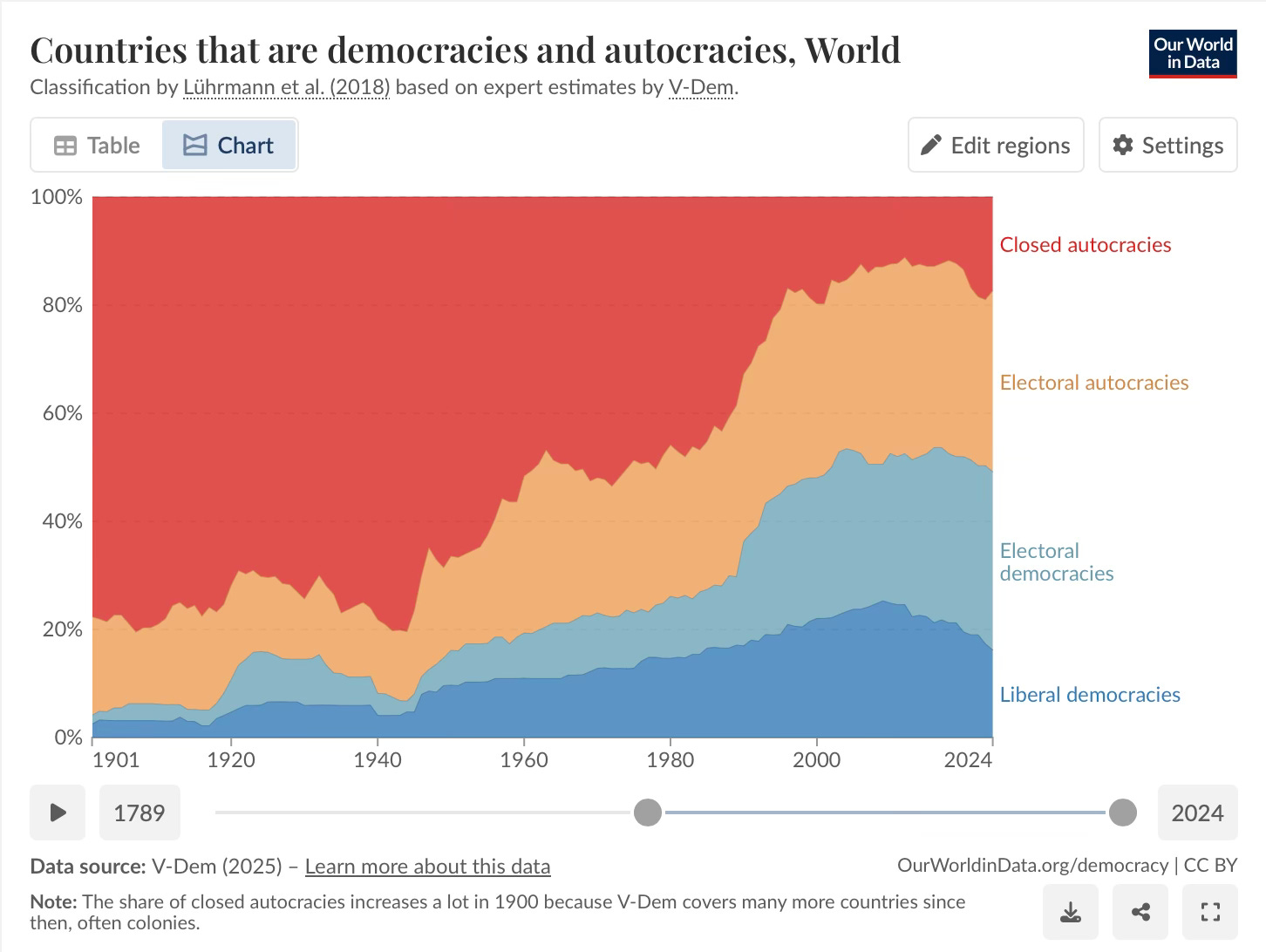

I am not Pollyanna. You’ll find plenty of bad news on Our World in Data. Some of the bad news involves slow, incremental progress turning into slow, incremental decline.

This is the chart that worries me most.

But still, take a look around. I guarantee you will find lots of slow, incremental changes for the better you weren’t aware of. Every one of them is another reason to hope.

In fact, let’s make this interactive. What is your favourite example of slow, quiet, little-noticed progress, whether gleaned from statistics or your personal experience? Leave a note in the comments.

Now, let me close with a photo of another swan.

This one is not a trumpeter. It’s a mute swan, in London’s Hyde Park, on a crisp December morning two years ago.

I share it because it was a wonderful morning that lingers in memory. And this particular swan is, I think you’ll agree, positively regal.

I loved this article. I spend weeks paddling in eastern Ontario every year, mostly on the Rideau Waterway. I started noticing the occasional trumpeter swan a few years ago, and dutifully reported them to the agency that was tracking them. A couple of years ago they notified me that there was no need to report anymore, the species was doing just fine. This made me very happy. My favourite swan story involves a flotilla of three who objected to my paddling too close to their spot. Being attacked in a kayak by three thirty-pound birds is a high point in my paddling career. Through sheer good luck I didn't capsize. They followed me relentlessly down the lake, squawking and strafing me as I sprinted away. These birds have attitude. You asked for another good news story: Loons are everywhere now. Ten years ago I photographed every one I saw. Now there are so many of them that I don't really bother, unless its an adult with young very close to the boat.

The trumpeter swan’s comeback is such a wonderful story . Anyone looking to dive deeper, check into the story of Ralph Edwards, the 'Caruso of Lonesome Lake.' He played a pivotal role in the 1950s by protecting a small group of swans near Bella Coola, BC, helping to ensure their survival in the region and likely the reason we are now seeing them regularly near us on Vancouver Island.