Technological Unemployment

Kurt Vonnegut and the long history of a jobless future

First: Picture a future in which immense productivity boosts churn out staggering wealth, like a molten river of gold lava flowing from a volcano.

Second: Picture a future that is a jobless wasteland, with unemployment rates permanently at Great Depression levels.

And finally, imagine a third future — a future in which the two preceding futures combine to form a bizarre new reality.

Among the many smart people trying to figure out what AI will become and what effects it will have on society, a considerable number think that third future is likely. Some are AI executives working hard to make it happen, such as Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, one of the major AI players, who made headlines when he said he expects that within the next one to five years AI will drive unemployment rates up to 20%. That is higher than the unemployment rate through most of the Great Depression. Geoffrey Hinton, the Nobel laureate and the “Godfather of AI,” recently said that if he had children deciding on a career path, he would tell them “train to be a plumber.”

This week on his podcast, Ezra Klein talked with

about the attention economy and the fate of Gen Z, which inevitably brought the conversation to AI — and the possibility of a future in which spectacular productivity gains exist alongside mass unemployment.Mid-way, Klein said something particularly important.

I think debates like that — whether we should welcome this productivity increase or try to stop it — will become much more salient in a way that people aren’t ready for yet, because they’re so used to technology just being adopted — as opposed to debated.

That’s exactly right.

One of the most important features of American democracy in the fifty or so years of the digital era is how little serious debate about technology there has been. Not “debate” in the sense of arguing “this technology will lead to that.” That sort of talk is constant. I mean “debate” in the sense of “do we want to do this? Maybe we shouldn’t.” That’s because the idea that we can collectively choose how new technology is deployed — or even whether it is deployed — is simply absent. When legendary investor Charlie Munger said crypto should be banned, he made a million eyes go wide. Ban a new technology? Inconceivable.

For decades, particularly in the United States, but also across much of the Western world, the assumption underlying almost all discussion of technology is that what will be, will be. We cannot stop it. We cannot shape it. We must simply adapt to it as best we can.

But that assumption is wrong. Categorically wrong.

By that, I don’t mean morally wrong. I mean incorrect. As the history of technology amply demonstrates, we do not have to simply accept and adapt. We can, collectively, choose.

To put it in pugilistic terms, if the relationship between people and technology were a boxing match, humanity has always been the stronger fighter. We still are.

But a boxing match is zero sum and the relationship between people and technology is decidedly not that. A much better metaphor is that of ballroom dance partners: They move together, each influencing the other, in an endless loop, which can be beautiful when it’s done right. But the dancers aren’t identical. One leads, deciding what the next move will be and communicating to the other with subtle gestures, shaping the dance.

In humanity’s dance with technology, people lead. Always have. Still do.

That’s actually the theme of my new series in this newsletter. And the book I’m working on now.

I used some of that fancy AI to create a little logo for the series. Here it is:

One of the interesting features of the discussion Ezra Klein had with Kyla Scanlon is how ahistorical it is. They talk about the present. They speculate about the future. But they say nothing about history.

Yet every theme in their conversation has deep historical roots. Some stretch back decades. Some, centuries.

In fact, as luck would have it, I’ve been reading an old and largely forgotten novel whose congruence with that podcast is downright eerie.

Here’s one illustration from the novel: The protagonist, Paul, is onboard a train which is entirely automated. Everything from the “all aboard!” to the checking of tickets to the driving of the train is done by machines.

Paul finds himself seated next to a retired conductor who grumbles that no machine could do everything he did in his 41 years working on the train before automation eliminated his job. “I’d like to see one of them machines deliver a baby,” he grouses. “And I never seen a machine yet that’d watch out for a little girl three years old all the way from St. Louis to Poughkeepsie.” And his final complaint: “With machines, you get quantitty, but you don’t get qual-ity. Know what I mean?”

This prompts Paul to be amazed “at what believers in mechanization most Americans were, even when their lives had been badly damaged by mechanization. The conductor’s plaint, like the lament of so many, wasn’t that it was unjust to take jobs from men and give them to machines, but that the machines didn’t do nearly as many human things as good designers could have made them do.” To me, that sounds a lot like Ezra Klein noting that Americans aren’t used to debating how or whether technology should be adopted “because they’re so used to technology just being adopted.”

The author of this long-forgotten novel? Kurt Vonnegut.

Player Piano was Vonnegut’s first novel, published in 1952. It got good reviews but was barely noticed and didn’t sell. It took 15 years and five more novels before Vonnegut became a star following the publication of Slaughterhouse Five in 1969.

But today, for anyone interested in the history of technology, and our relationship with technology, Player Piano is fascinating.

A “player piano,” as everyone knew in 1952, is a piano that uses paper rolls dotted with punched holes to play tunes by itself. A human is only needed to put the roll in and mindlessly pump a pedal. The machine does the rest.

In Player Piano, Vonnegut imagined a future in which automation has turned all of America into one enormous player piano. Industry is fantastically efficient and productive under the leadership of a single technocratic organization that runs all of society like a perfectly tuned and oiled machine. Punch cards sum up credentials and aptitudes and assignments, and every person’s fate is determined by the arrangement of the holes on their card. For the few with the right combination of IQ and degrees, the system makes them engineers and managers. They are rich. But the fate assigned to most is mediocrity — working as a poorly paid lackey to the technocrats — or unemployment. No occupation has been spared. The engineers are even on the cusp of creating “electronic writers.” (How chilling….)

Given that the novel was published in 1952, and we, today, think of the 1950s as a golden era of full employment and rising prosperity, Vonnegut’s concept may sound out of synch with his times. It was not. In fact, Player Piano is very much a product of the years leading up to its publication.

The Great Depression of the 1930s had generated staggering levels of unemployment. As it ground on with little sign of relief, one of the leading explanations for the disaster was technological: Production had become so efficient, it was widely believed, that most labour was surplus. And as science and technology advanced, the problem would only get worse.

Fears of permanent mass unemployment temporarily eased when millions of men were sent to fight the Second World War, but many observers — including economists — believed that the dismal process would resume in the post-war years.

That was the context in which Vonnegut wrote Player Piano. And Vonnegut had a personal perspective on the issue.

His father was a successful architect whose practice was ruined by the Depression, and his family, like so many others, plunged from wealth and social standing into poverty. It was a shattering experience for both his parents. Vonnegut was ten years old at the height of the Great Depression. Witnessing his parents’ degradation — he later said his mother turned bitter and vicious — must have been searing.

Vonnegut went on to study mechanical engineering before dropping out to join the US Army in 1943 and it’s hard not to see the author in his protagonist, Paul, a mechanical engineer who turns against the system. Why do we let them take jobs from men and give them to machines? Paul wonders. That’s the nagging theme of the novel, one which defenders of the status quo — the engineers and managers of the technocracy — have developed glib answers for.

At an organizational retreat, the technocracy’s top people watch a play in which the system is literally put on trial, with an unemployed worker named “John” brought to testify. Seeking to convict the system, a man identified only as “radical” examines the witness.

What happened to your income after the system was introduced, the radical asks.

“Well, sir, when the defense work and all got going before the war, seems to me I could make better’n a hundred a week with overtime. Best week I ever had, I guess, was about a hundred and forty-five dollars. Now I get thirty a week.”

“To be exact, John, your income dropped about eighty per cent,” the radical notes.

To cross-examine the witness, and defend technocracy, a young engineer steps up.

YOUNG ENG. John, tell me—when you had this large income, before the star arose, did you by any chance have a twenty-eight-inch television set?

JOHN. (Puzzled) No, sir.

YOUNG ENG. Or a laundry console or a radar stove or an electronic dust precipitator?

JOHN. No, sir, I didn’t. Them things were for the rich folks.

YOUNG ENG. And tell me, John, when you had all that money, did you have a social insurance package that paid all of your medical bills, all of your dentist bills, and provided for food, housing, clothes, and pocket money in your old age?

JOHN. No, sir. There wasn’t no such thing then, in those days.

But John has all this abundance now — thanks to technology and technocracy!

John is not deprived. John is blessed!

YOUNG ENG. John, you’ve heard of Julius Caesar? Good, you have. John, do you suppose that Caesar, with all his power and wealth, with the world at his feet, do you suppose he had what you, Mr. Averageman, have today?

JOHN. (Surprised) Come to think of it, he didn’t. Huh! What do you know?

RADICAL. (Furiously) I object! What has Caesar got to do with it?

YOUNG ENG. Your honor, the point I was trying to make was that John … has become far richer than the wildest dreams of Caesar or Napoleon or Henry VIII! Or any emperor in history! Thirty dollars, John—yes, that is how much money you make. But, not with all his gold and armies could Charlemagne have gotten one single electric lamp or vacuum tube! He would have given anything to get the security and health package you have, John. But could he get it? No!

In the novel, the play is written by one of the technocracy’s wealthy managers, but slip in a reference to Universal Basic Income and it reads like something Marc Andreessen would write with the help of ChatGPT.

Notice that the young engineer’s defence of technocracy rests entirely on material conditions. Sure, John is out of a job and his income has shrunk. But he has a twenty-eight inch television set and healthcare. What more could a man want?

The play doesn’t touch that question because the technocrats are oblivious to it. But it’s at the heart of the novel.

What Vonnegut drills home in Player Piano is that a job is much more than a way to get material goods and services. It provides purpose, dignity, even identity. The technocracy cannot compensate for the loss of those. It isn’t even aware they have been lost.

The agony experienced by the unemployed in Player Piano is less material than spiritual, a reality made brutally apparent in the form of a make-work organization grandly called the “Reconstruction and Reclamation Corps.” Its “workers” aren’t fooled. They flush sewers and patch potholes. Anything to keep them busy. Everyone knows them as the “Reeks and Wrecks.” They call themselves that. They are surplus. Disposable. They are nothing.

Materially, they’re getting by. Spiritually, they are crumbling.

These are old themes. Ancient, even.

In the century prior to the Great Depression, waves of new technologies turned skilled artisans into unskilled machine-tenders, or left them entirely unemployed. Some tried to smash the machines taking their livelihoods. The Luddites are famous even today, thanks to the addition of “Luddite” as a word heaping scorn on those who oppose technological progress, but there many others like them. The Silesian Weavers is an 1844 poem by Heinrich Heine about German weavers — the Luddites were weavers, too, as textiles were among the first products to be mechanized — who led a futile rebellion against wage cuts.

Even in the early 19th century, this was an old and familiar pattern.

All the way back to the Middle Ages and beyond, some clever person would occasionally figure out a way to do the work of ten men with two, and these attempts to improve productivity were met with hostility from all those doing that work. But how did the ruling classes adjudicate these conflicts? That is something that has changed in modern times.

In the distant past, the potential benefits of disruptive technology were often little appreciated by anyone save those directly pocketing the savings. And disruption was seen as inherently bad in conservative societies where preservation of the status quo was a sacred duty. So when new technologies were met with hostility, rulers often backed opponents and banned the technology. There is even a theory — which I find compelling — that a key reason why Britain was the first to undergo Industrial Revolution is that Britain was the first country in which the ruling classes refused to side with the status quo and permitted the widespread adoption of labour-saving technology. (See Carl Benedikt Frey’s brilliant The Technology Trap.)

Several years ago, in the brief period when fully autonomous vehicles were widely believed to be months away, and they would quickly erase millions of jobs driving trucks, far-right commentator Tucker Carlson said flatly he would ban the technology. It caused a stir. Ban a brilliant new technology? Simply because it would eliminate jobs? It sounded bizarre. Yet what sounds bizarre in modern America was common in the past.

For the record, I am very much not a Luddite. Machines may indeed wipe out jobs, but they can also make life easier and better, and the wealth they generate can create new jobs, often of a sort that can’t be imagined at the time they are eliminating jobs, leaving later generations much better off. Early in the 20th century, AT&T was the largest employer in the United States, and half its employees were operators manually connecting phone calls. Automation erased those jobs. Nobody misses them.

So, I agree with the technology boosters: Humanity has been vastly enriched by accepting the disruption that comes with technological advance.

But many tech boosters are far too glib abut the costs of technological disruption. Try telling a 45-year-old man who finds himself permanently unemployed — his education, skills, and experience all rendered useless — that he should be happy because the technology that put him out of work is boosting the nation’s GDP and one day his children may get some unforeseeable new type of job. He will hit you, if he’s not stoned on fentanyl. And he would be right to. Because what too many tech boosters shrug off as nothing more than a period of disruption and adaptation — a mere blip — may be the remainder of his life. People deserve better than to be consigned to the Reeks and Wrecks.

Many tech boosters also tend to blithely assume that, in time, tech automatically lifts all boats. That’s simply not true. As Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson showed in Power and Progress, the wealth created by new, productivity-boosting technology does not automatically flow to the benefit of all but is instead more often captured by a relative few. Only with concerted political effort have the few been compelled to share with the many. Remember how I said “we choose” if and how to adopt new technology? This is a big chunk of the choices we need to make.

And finally, there is always the possibility that, to use the old phrase, “this time is different.” It is true that for more than two centuries the adoption of disruptive new technology that eliminates jobs has created more wealth and abundant new forms of employment. And it is true that, as in the 1930s, many people in the past have incorrectly believed that “this time is different” and high unemployment was permanent. That history suggests fears of an AI-induced era of unemployment overwrought. But they do not guarantee it. As always, this time really may be different.

Contrary to so many others, who seem to think they have it all worked out, I am utterly uncertain about how AI will unfold, in part because I recognize that forecasting that future requires far more than an ability to forecast the technology’s development, as difficult as that is. There are hosts of political, cultural, and economic questions involved. Change the answers to any one of those and the future changes. I think that is a forecasting challenge beyond the capability of anyone. Or any machine.

So as so often, we are left to simply contemplate the range of possible futures. And it is immense. I can easily imagine a future in which AI development using existing techniques hits insurmountable walls (as it has done multiple times over the almost seven decades since the term “artificial intelligence” was coined), the AI investment bubble bursts, and the wilder hand-waving of the past couple of years — good and bad — looks ridiculous in a decade or two. But I can also imagine a future in which AI produces great disruption, wealth, and such amazing new jobs and life-enhancing abilities my grandchildren pity me for having lived in these benighted times. And I can imagine a future in which AI has spawned a handful of tech trillionaires along with hundreds of millions of unemployed white collar workers, and my grandchildren’s only shot at a job is working for the private militias guarding the rich.

Between these extremes, of course, I can imagine a thousand other futures.

If I had to bet, I’d put my money on some middling, contradictory, confused, messy scenario containing far less drama than any of the more extreme possibilities. The reason for that bet? New technologies have routinely inspired extreme expectations in the bewildering first few years of their development — The future will be heaven! No, the future will be hell! — but what actually unfolded was neither heaven nor hell but the middling, contradictory, confused, messy world we live in. So that’s the base rate. And a good forecast always starts with the base rate.

I am, however, quite confident about one particular forecast: We will talk a lot more about technological unemployment in the next few years. Which makes the long history of technological unemployment important to grapple with now.

You can start by reading Player Piano.

Bonus Tracks

Canuck fact-checking

My fellow Canadians will remember Kevin Newman as a top-tier broadcast TV news anchor, host of Question Period, contributor to W5, and more. Americans with as much grey hair as I have will also know Kevin from the decade he spent on American TV as an anchor with ABC News and co-host of Good Morning America.

No longer doing the daily journalism grind, Kevin is keeping busy in the most appropriate way possible: He’s part of “Get Fact,” a group that is doing fact-checking of claims in the news with the help of “Laura,” the group’s own AI fact-checker.

Give it a try here. And consider kicking in. In this world, God knows, every effort to keep the collective mind sane and informed is on the side of the angels.

Epic novels in the news

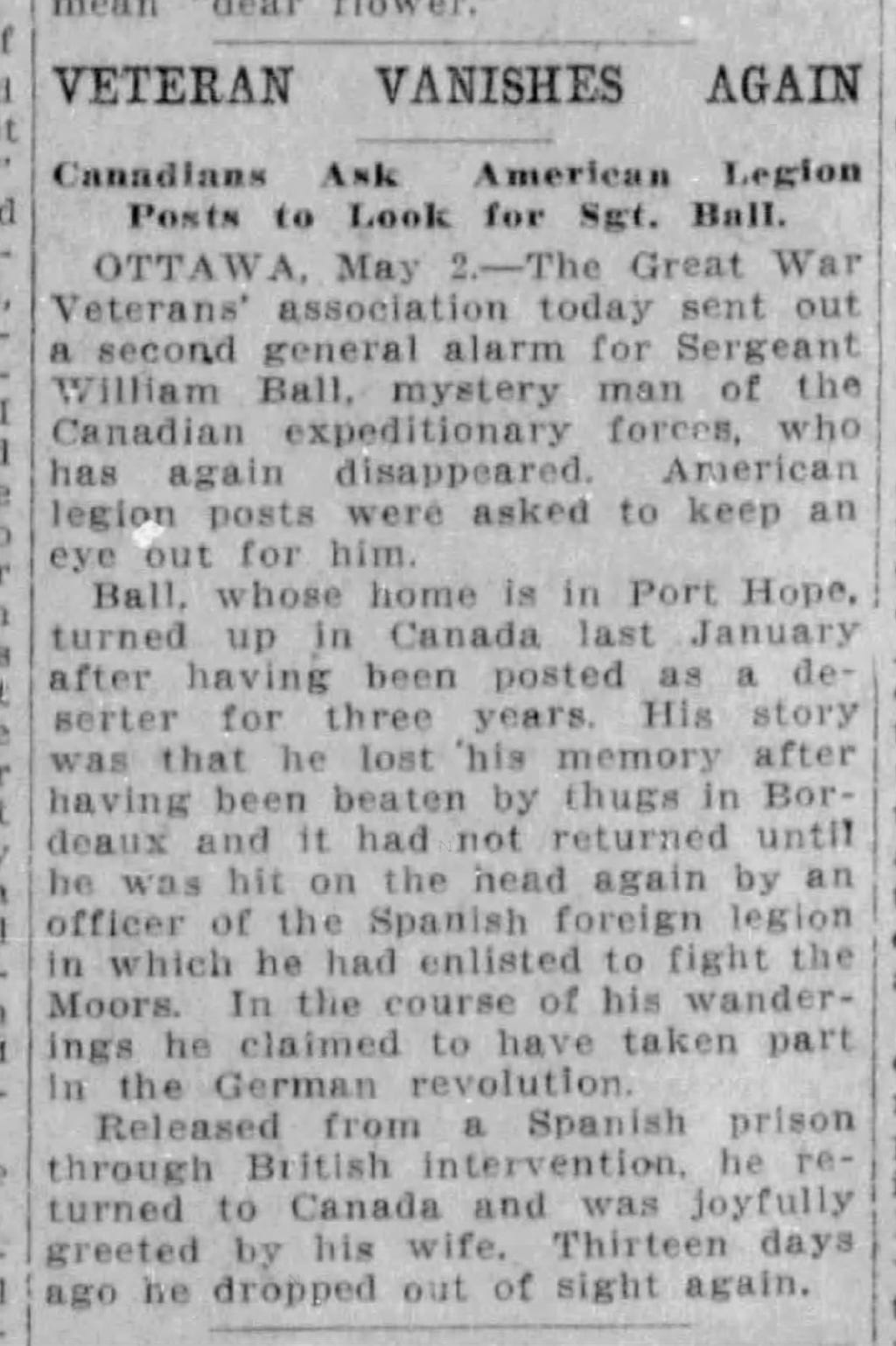

I spend a lot of time looking through old newspapers and magazines. Every now and then I come across some little snippet that hints at an underlying story so vast and dramatic it should be a sprawling novel.

Here is one.

From the Spokane Spokesman-Review of Spokane Washington, dated May 3, 1922:

What major achievable and sustainable technologies have we banned? It’s a genuine question, something I’ve thought about in the context of nuclear weapons (I think it’s unrealistic and fantastical to have expected Truman to have had the atom bomb explained to him and to have said “No, we won’t use it, this is a technology we won’t pursue, that we’ll effectively put beyond use”).

Well said. Reminds me of the video on YouTube “Is an AI Apocalypse Inevitable?” by Tristan Harris. The author points out that social media as currently designed didn’t have to be this way, but society wrote it off as inevitable. He uses nuclear weapons regulations as an example of collective decisions about technology that can work in practice.