Technology = Experience

Design narrows because experience teaches

I don’t think I’m giving away the plot if I note that in my forthcoming book — ahem — there’s an important point about the value of experience: It isn’t only people who are shaped, honed, refined, and improved by experience. It is technology.

We can see this in the history of the bicycle. The earliest designs were almost comically varied. Two-wheeled-scooters. Three-wheelers. Four-wheelers. Two-wheelers with a small wheel in front and a large wheel behind. The “penny-farthing,” or “high wheel,” in which the rider sat atop a huge front wheel with a second, tiny wheel behind. Experience with these designs revealed some things worked well, while others did not, and a few ideas were hare-brained and dangerous. These lessons were shared and informed subsequent designs. By the 1890s, designs merged into the basic idea of the modern bicycle: two wheels of the same size, in line, with a frame, seat, and handlebars, plus pedals and chain for propulsion. It was an excellent design — because there was decades of experience embedded in it.

That wasn’t the end of innovation, naturally, but innovation has, almost always, occurred within those design parameters. Go to your local bike shop and you will not find some new iteration of the penny-farthing. But you will find a breathtaking number of iterations in line with forms established a century-and-a-quarter ago. (I bought a gravel bike this spring. Prior to that, the last time I bought an adult bike was 1997, and I was stunned to see how much bicycle technology had improved in the last 25 years — a century after the bicycle’s basic modern form had been settled. And yet nothing I saw differed in terms of the basics established in the 1890s.)

The idea that the things we use can be more or less experienced, just as people are more or less experienced, and we should value this experience just as we value experience in people, is a basic stuff. But it’s remarkable how often it is overlooked in a world where the word “new” is treated as a synonym for “better.” So in the book Bent Flyvbjerg and I make the elementary but important argument that, no, “new” is not a synonym for “better.” All else being equal, we should prefer more experience over less — in things as in people.

Then the other day I watched All Quiet On The Western Front.

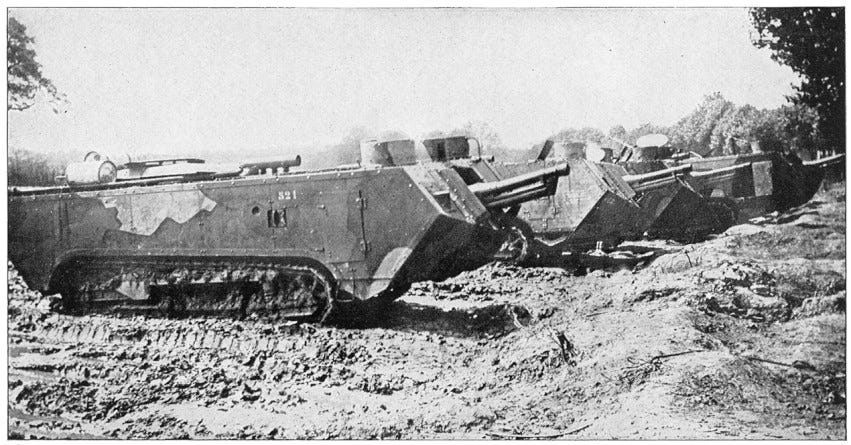

It was a new German production of the classic book now on Netflix. (It is superb and worth your time. It is also devastating. You have been warned.) In that movie — no plot spoilers here, don’t worry — there is a scene in which a French attack is led by tanks. More specifically, it is led by French Saint-Chamond tanks. The Saint-Chamond looked very different from tanks of the Second World War, much less later tanks. Instead of the basic shape of a tank, so familiar to us, the Saint-Chamond was more like a metal shoebox on treads with a single gun sticking out the front of the shoebox. I’ve never seen the Saint-Chamond in a move or TV show before, so it really caught my eye.

I realized I was looking at the perfect illustration of how experience is embedded in technology.

Prior to the First World War, cars with internal combustion engines were increasingly common and reliable. So were trucks. Militaries were making growing use of them. Inevitably — this doesn’t take much imagination — vehicles had metal welded to their sides and guns stuck on top, creating the armoured car and the armoured truck many years before Germany invaded Belgium in August, 1914.

But outside the fertile imaginations of a few individuals, tanks did not exist.

As I’m sure everyone knows, the initial rapid assaults of the First World War soon bogged down into the infamous stalemate of trench warfare. Ordinary tactics failed. No matter how large the assault. No matter how many men died.

This was a shocking development to strategists. In desperation, combatants authorized a wide array of experiments. Most came to nothing. But in Britain, one such effort was the “Landship Committee,” established by First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill in February, 1915, which Churchill created in secret because he thought his superiors would block it. (Churchill was always that kinda guy….) When it was realized that “landship” gives the idea away, the thing being designed was given the codename “tank” and the committee’s name was changed to the superbly bureaucratic and boring “Tank Supply Committee.” This program gave rise to the first tank to enter combat, the Mark 1.

Similar efforts got underway in France and Russia. Germany started its own program only after being shocked on the battlefield by British tanks.

All these countries were trying to solve the same problem: The terrain of the static battlefield was brutal.

Trenchlines, barbed wire, giant craters. Smashed tree stumps. Heaps of debris and rubbish. Oceans of mud. What sort of vehicle would be able to travel across that? What sort of armour would it need to keep from being smashed to pieces by enemy guns? What sort of weapons did it need to blast through enemy trench lines?

About the only thing the designers knew was that existing armoured cars and trucks were completely useless in that environment. Beyond that, the drafting table was blank.

We all know what the solution ultimately was, so I’ll skip straight to it. Following are some of the basic tank types in use at the start of the Second World War, whose design reflected the lessons learned in the First World War.

Like the bicycle of the 1890s, these tanks all have the same core design: roughly similar size, low, squat metal body on treads, gun in a turret capable of turning independently of the body. These are the obvious features. They share many others that are not so evident, such as the thickness of armour, size of engine, etc. They also differ, of course. But they are broadly similar in the way bicycles of the 1890s and subsequent years were broadly similar.

But now look at some of the earliest designs for tanks in the First World War, starting with the Saint-Chamond, followed by the British Mark I, the first tank to enter the war.

Even if you know nothing about tanks, a quick glance is enough to see these are radically different designs.

Even the scale of these vehicles varies widely. See the French Renault FT (third from the top of World War One tanks)? It has a crew of two. The German A7V (last) had a minimum crew of eighteen and could hold up to twenty-five.

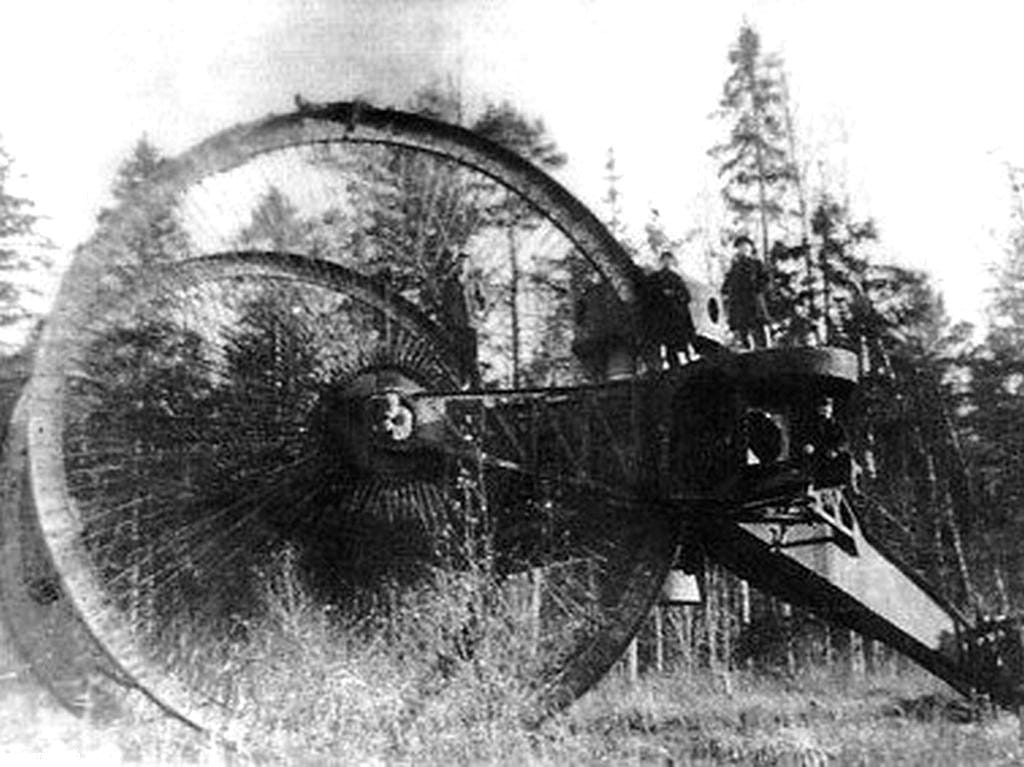

Also note that the one commonality (almost) all had was the continuous track instead of wheels. Why do they (almost) all have that? Because that was an existing, proven technology, developed for bulldozers and tractors, dating back to the 19th century. The one exception is the Russian “Tsar,” which experimented with the idea of wheels so gigantic — they are nine metres (almost 30 feet) high! — they could simply roll over anything. It was a daring experiment but it didn’t work. The tracks did. So in future, all tanks had tracks.

Something that isn’t obvious about the little Renault FT is that it has a turret that turns, so its gun can aim independent of its body. None of the others has that. Experience proved that to be an invaluable feature. Twenty years later, all tanks had rotating turrets. It became impossible to even imagine a tank without one. Which explains why the Renault FT, size aside, looks more like the Second World War tanks than all the others.

That is experience shaping design. Or if you prefer, experience becoming embedded in design.

We often fail to appreciate the value of experience in design because we see new designs as advances on old, which makes “new” a synonym for “better.” But “new” is, by definition, an experiment. Run the experiment and see what happens. Run it many times. If the experiment delivers good results, “new” will indeed mean “better.” But you will know that not because it is new. You will know that because you have the results of those experiments.

Which is to say, you will know that thanks to experience.

Great insights and lessons.

I, of course, immediately apply this lesson to my favourite hobby, pinball. Early pinball tables were hugely varied. They all had some kind of plunger that launched the ball to the top and it'd trickle down and hit different stuff, but after 50 years or so the first machine was created with flippers… all over the place [0]. Then within a decade or so of experimentation the "Italian Bottom" [1] took hold and now every pinball machine has two flippers facing each other on the bottom, with two inlanes, and two outlanes. Every couple decades someone will try to deviate, but it's never popular.

[0] https://www.ipdb.org/machine.cgi?id=1254

[1] https://www.thisweekinpinball.com/understanding-the-italian-bottom/

Is the problem here that while new is not always better, better will usually be new.