“I don’t anticipate stagflation.” With those words in 2008, Ben Bernanke, then the chair of the United States Federal Reserve, revived a word redolent of bell bottoms and disco. For those who knew what “stagflation” meant.

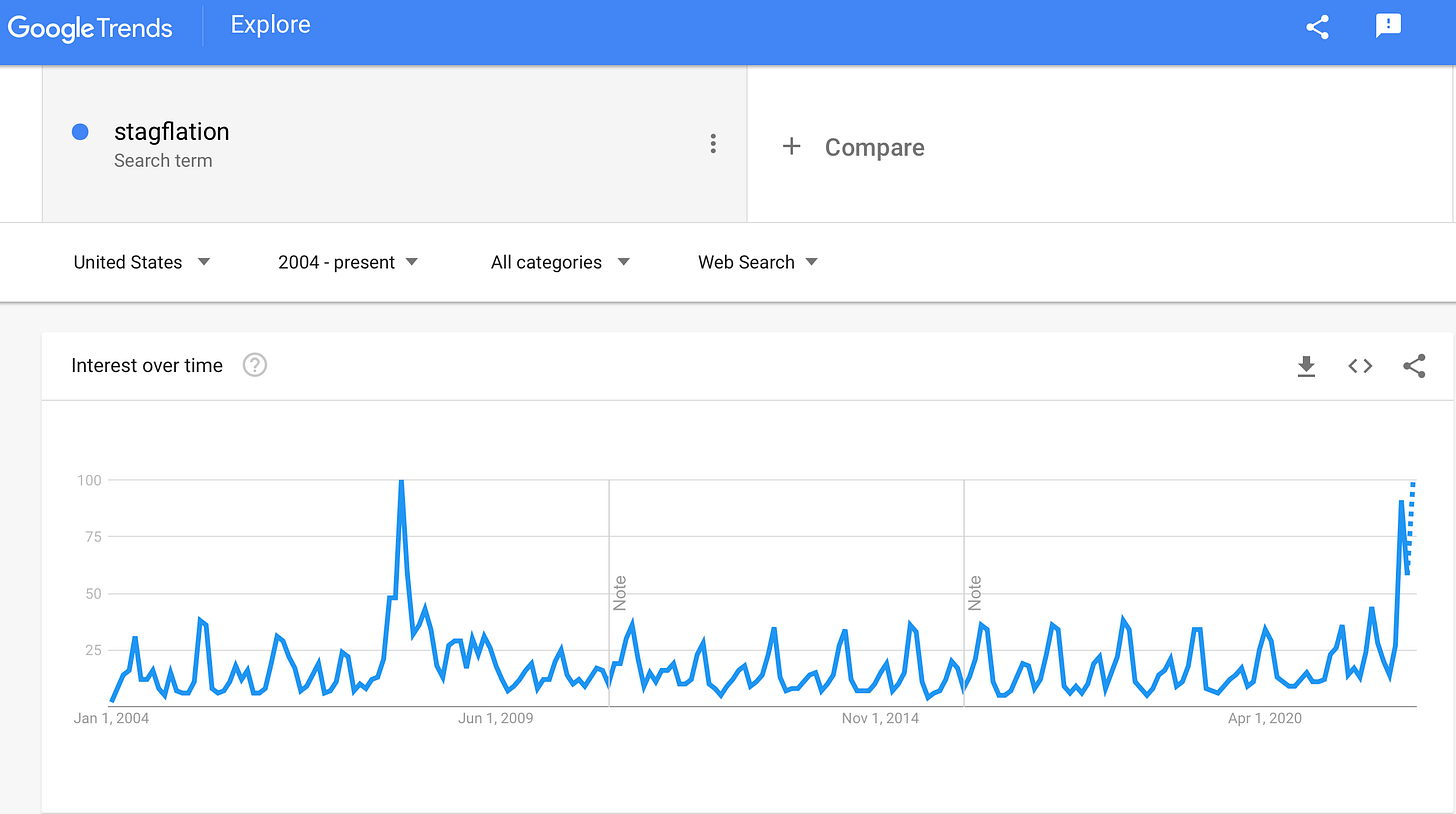

Apparently, that didn’t include a lot of Americans, as Google searches for “stagflation” shot up. But only briefly. Because Bernanke was right.

The United States wasn’t facing stagflation. Prices for oil and many other commodities were soaring in the first half of 2008 — anyone remember the “Age of Scarcity” panic in the spring of that year? — but it wasn’t 1973 barrelling at us then. It was 1929. (Fortunately for us, Mr. Bernanke happened to be a leading expert on the Great Depression, a big reason why the Great Recession never got that bad.)

But now here we are in 2022. For the first time in four decades, inflation is roaring across much of the Western world and central banks are fighting it by jacking up rates at a furious pace — raising fears they may do considerably more than slow an overheated economy. Which may not even stifle inflation.

If the worst happens, we would have both inflation plus a stagnant economy. Or to use the word coined in the Nixon era: “stagflation.”

If that comes to pass, 1973 will indeed be barrelling at us like a gold Chevrolet Monte Carlo with swivel bucket seats and an eight-track blasting Mott the Hoople.

So what would that mean? Thanks to Google Trends, I’m pretty sure lots of people have little idea. Here’s a chart of Google searches for the word “stagflation” in the United States. The first spike follows Bernanke’s 2008 comment. The second is … now.

And so as a service to those of you unfamiliar with the term, here are a few short passages about inflation and what happens when it coincides with a long period of low growth. (Spoiler: It’s bad.)

First up, Robert Shiller. The Nobel laureate is a behavioural economist, meaning he thinks about people like they’re human, not ambulatory calculators. Which puts him in the minority among economists.

In his most recent book, Narrative Economics, Shiller has a warning:

Out-of-control consumer price inflation has occurred many times throughout history, and the phenomenon has always induced anger. The loss of purchasing power is extremely annoying. But the question is this: At whom should the public direct its anger?

Shiller notes that extreme inflations often happen during war because hard-pressed governments are tempted to set printing presses to brrrr. Logically, the anger should be directed at those governments. But remember, these are humans we’re talking about, so logic is of limited use.

…the stories may not resonate, and the public may not see or understand what is happening. That is, narratives that blame the government for the inflation may not be contagious during a war. Instead, it is more likely that people want to blame someone else. Businesspeople, who are staying home safely while others are fighting, are a natural target for narratives.

This is why “profiteer” is so often the nastiest cuss-word of wartime.

Shiller published Narrative Economics in 2019 and he noted that inflation was still low. But if it rose substantially in future, it would …

…create a strong impulse for economic actors to get ahead of the inflation game. It could give them newfound zest in this effort by bringing a moral dimension into the mix, a perception of true evil in inflation, personified by certain celebrities or classes of people.

Anger. Lots of anger. Anger that can be channelled and focussed by unscrupulous actors. That sounds very 2022, doesn’t it?

There is a potential upside, however. For some people.

Ordinary people could score an inflation windfall of their own simply by buying a house. Hundreds of thousands of California and Florida bungalows, bought in the early 1960s for less than $35,000 on five percent mortgages, were suddenly tripling and quadrupling in value. “What sellers are asking,” gasped a California magazine writer, “is sometime staggering. A one-bedroom wooden shack in Benedict Canyon with only 22-by-26 feet of living space goes for $71,000. Why? It’s located in the fashionable Beverly Hills post office district.” Over the three years 1972-1975 the median price of a new home in the United States jumped by nearly 50 percent. Worse than the rise in housing prices was the rise in interest rates. Baby boomers who had grown up in homes financed at 4.5 percent were by 1975 facing mortgage rates that had passed 9 percent. In 1950, seven out of ten American families could afford the monthly payments on a median-priced new home; by the end of 1975, only about four of ten families could.

So people who own homes see their values soar, while everyone else is screwed. That also has an early 2020s vibe.

(The passage above, by the way, comes from How We Got Here: The decade that brought you modern life — for better or worse by David Frum. Yes, that David Frum. He published it in 2000 and soon started work in the White House, where he wrote some things you may be more familiar with.)

Cost of housing aside, stagflation had social consequences so profound that, as historian Bruce Schulman noted in The Seventies, we are living with them to this day.

Depression babies — people who grew up in the 1930s — possessed a certain approach to life, a certain suspicion of good times, a thriftiness, a tendency to reuse tea bags and never throw anything away. The Great Inflation produced its own generation, altering Americans’ relationship to money, government, and each other.

First, Americans developed dramatically new attitudes toward credit and credit cards. In 1973, when Dee Hock, creator of the Visa card, installed his computerized authorization system, credit card spending totalled nearly $14 billion and was growing at a brisk by not outlandish clip of about $3.5 billion a year. But over the next decade, it roared ahead, reaching $66 billion by 1982, almost a fivefold increase.

Credit cards made it easier for Americans to borrow, but plastic was not the only reason, or even the main reason, for the broader cultural shifts in attitude toward spending and debt. Credit cards just provided an easy way to borrow more. In 1975, for instance, credit card debt hovered around $15 billion, but total consumer borrowing reached an astounding $167 billion. By 1979, it had almost doubled again, to $315 billion. Credit cards did not turn thrifty Americans into borrowers. The Great Inflation did.

Until the 1970s, there had been a generalized resistance to credit and debt. Borrowing remained tainted, a sign of moral weakness. Thrift had long been the great American virtue: remember Benjamin Franklin’s admonition against waste and excess in his Autobiography. But with double-digit inflation, thriftiness became just plain dumb. Saving money meant paying for tomorrow’s higher-priced goods with yesterday’s diminished dollars. Borrowing, on the other hand, made sense. You could purchase something today, before the price went up, and pay for it later with inflated dollars that were worth less.

… A new zest for credit was one major consequence of the Great Inflation. And then there were money market funds. The Great Inflation changed Americans from savers to investors.

The America that, in the late 1990s, couldn’t pour money fast enough into any stock with “dot com” in its name; the America that, in the 2000s, saw rising home prices as an opportunity to pull out equity and buy new giant screen TVs and Ford F-150s; the America that, in recent years, shovelled money furiously into crypto currencies with the expectation that everyone would get rich — that America could never have come into being without the stagflation of the 1970s.

Beyond dollars and cents, economic strain can be a force multiplier of other social stresses. Americans knew that when stagflation came. In part because of that, fear of the future was a leitmotif of the 1970s and the decade became a golden age of this-is-bad-but-it’s-going-to-get-so-much-worse books and essays.

The following gives a little of the flavour of the time. By the summer of 1971, the US had suffered escalating racial conflict for more than half a decade, so with stagflation adding to the country’s woes, the prognosis was grim. From the Tampa Tribune, June 20, 1971:

Stagflation survived the 1970s. Paul Volcker, the Fed chairman appointed by Jimmy Carter in 1979 and kept on by Ronald Reagan, decided to finally throttle it by pushing interest rates skyward. To put Volcker’s policy in perspective, here is a chart of the Fed’s fund rate from the 1970s to today.

See that tiny tick upwards at the end? That’s the surge in interest rates now on-going, the one that seems so big and dramatic. In this light, Volcker’s approach can be seen for what it really was: the central bank equivalent of Russia’s scorched-earth defence against Napoleon.

In 1979, a full-page ad appeared in The New York Times: “IN THE GREAT DEPRESSION OF THE 1980's, MOST INVESTORS WILL BE STUNNED BY THEIR LOSSES: MANY WILL BE UTTERLY DESTROYED: A CANNY FEW WILL NOT ONLY SURVIVE, BUT PROSPER.” The canny few, of course, were those who bought the advertised book.

Several weeks later, another full-page ad appeared: “MOST OF WHAT YOU HAVE WILL BE WIPED OUT IN THE COMING CURRENCY COLLAPSE.” Purchasers of the advertised book would avoid calamity, naturally.

But even more sober economic analysts saw trouble coming. it was all but inevitable given that the fed was strangling the economy like Homer with his hands around Bart’s neck, to use an anachronistic reference.

The economy fell into a double-dip recession so brutal it convinced some economic observers that the US was entering the Second Great Depression. In the early 1980s, Reagan became so unpopular that even some of those close to him — including Nancy — thought he shouldn’t or wouldn’t run for a second term.

But finally inflation gave up the ghost, Volcker eased interest rates, and the economy roared to life — just in time to get Reagan re-elected in a landslide.

(It’s worth underscoring that both Carter and Reagan backed Volcker’s strategy, at great political cost to each. But Carter’s re-election campaign came too late to save him, while Reagan’s was just late enough, which is why Carter is remembered as a one-term failure while Reagan’s name is honoured on airports, schools, and highways all over America. In politics, as in comedy, and knife-throwing, timing is everything.)

To sum up: Stagflation is awful, the cure is a nightmare, god help us all.

Of course it’s possible that rising central bank rates will, as intended, cool the economy and quickly douse inflation without pushing us into recession. There will be no stagflation, as there was none in 2008 and 2009. If that happens, the word may once more lapse from public consciousness.

Ben Bernanke and Company saved us from the worst during the financial crisis. Let’s hope they can pull it off again.