Anyone who reads newsletters like PastPresentFuture doesn’t need to be reminded about what’s happening in America, and what it could mean for the world.

On January 20th, the new president will be a man who has never shown the slightest interest in the vision of the United States as a “shining city on a hill.” A man who praises strongmen and dictators, bullies friends and allies, and sneers at “shithole countries.” A man who — like some 18th century mercantilist teleported to the 21st century — thinks imports create poverty and tariffs prosperity. A man who feels nothing but contempt and hostility for the post-Second World War Pax Americana, the American-forged and American-led international order that, however flawed, delivered an unprecedented era of human flourishing.

The world as we have known it since 1945 is swaying, as if in an earthquake, threatening to topple.

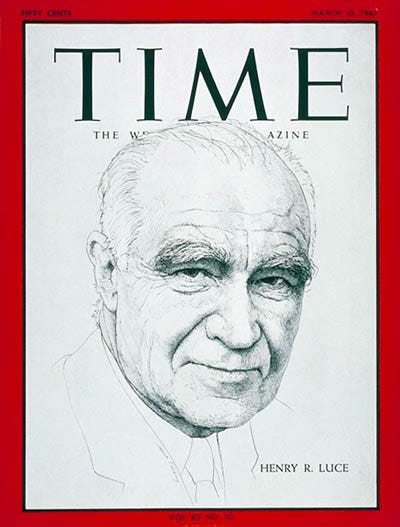

You know all that. So today I want to go back to 1941 and look at some passages taken from an essay written by Henry Luce. I think you’ll agree that the contrast between Luce’s words then and what we are hearing now is both illuminating and profoundly sad.

Henry Luce was the legendary founder of Time (1923), Fortune (1929), and Sports Illustrated (1954.) In 1936, Luce also bought a minor humour magazine named Life, focused it on photojournalism, and turned it into the chronicle of mid-20th century America.

By 1939, when war broke out in Europe, Luce was easily one of the most prominent and influential voices in the United States. But his voice mattered far beyond the United States because America did then would shape the fate of the world.

What American mostly did was nothing.

President Franklin Roosevelt was an internationalist who wanted to intervene in Europe but couldn’t because in 1939 Congress was overwhelmingly isolationist. So was American society. That feeling was the product of half a century of history.

From the early 1890s until 1918, growing American economic power and international trade — along with the acquisition of a handful of overseas territories — had fostered a rising sentiment in the United States that traditional American isolationism was no longer tenable and the United States had no choice but to get involved in foreign affairs. That reached a crescendo when President Woodrow Wilson abandoned neutrality in 1917 and took the United States into the Great War. Wilson’s “fourteen points” for a post-war settlement fuelled imaginations worldwide. When victory came in November, 1918, American leadership was a given. Wilson would dominate the peace talks, get his “League of Nations,” and the United States would finally take its place at the head of the international table.

But Wilson was politically inept. Worse, his health crumbled and he suffered a paralyzing stroke in 1919. When the American economy plunged into a severe recession, the popular mood swung abruptly from jingoistic internationalism — the doughboys were going “over there” to make the world “safe for democracy” — to one of angry, resentful, paranoid retrenchment. In 1920, when Republican Warren Harding promised to sweep away all this new internationalism and bring “a return to normalcy,” he won the White House. Isolationist Republicans dominated the 1920s and Americans became convinced that going to war in 1917 had been a terrible mistake (orchestrated by Jewish bankers, added Henry Ford and millions of others). When the Great Depression struck, the collapse of American industry and the unprecedented suffering coast to coast further entrenched the feeling that American should take care of itself and to hell with the rest of the world.

At first, the outbreak of war in Europe changed little. This was the era of the “America First Committee” and warnings that support for Britain risked dragging American into a war (that would only benefit Jewish bankers, whispered many America Firsters.) Following Hitler’s conquest of Western Europe in the spring of 1940, Roosevelt accelerated re-armament at home and the provision of military supplies to Britain, which isolationists opposed on the grounds that the war was already lost and Winston Churchill’s obstinacy would only get more people killed for nothing. (An argument recently reprised by “America’s best popular historian” — according to Tucker Carlson — and promoted by Elon Musk.) But Hitler’s campaign of naked conquest reduced what little sympathy the broad American public had for Nazi Germany and bolstered backing for Britain. “All support short of war” became an increasingly popular position.

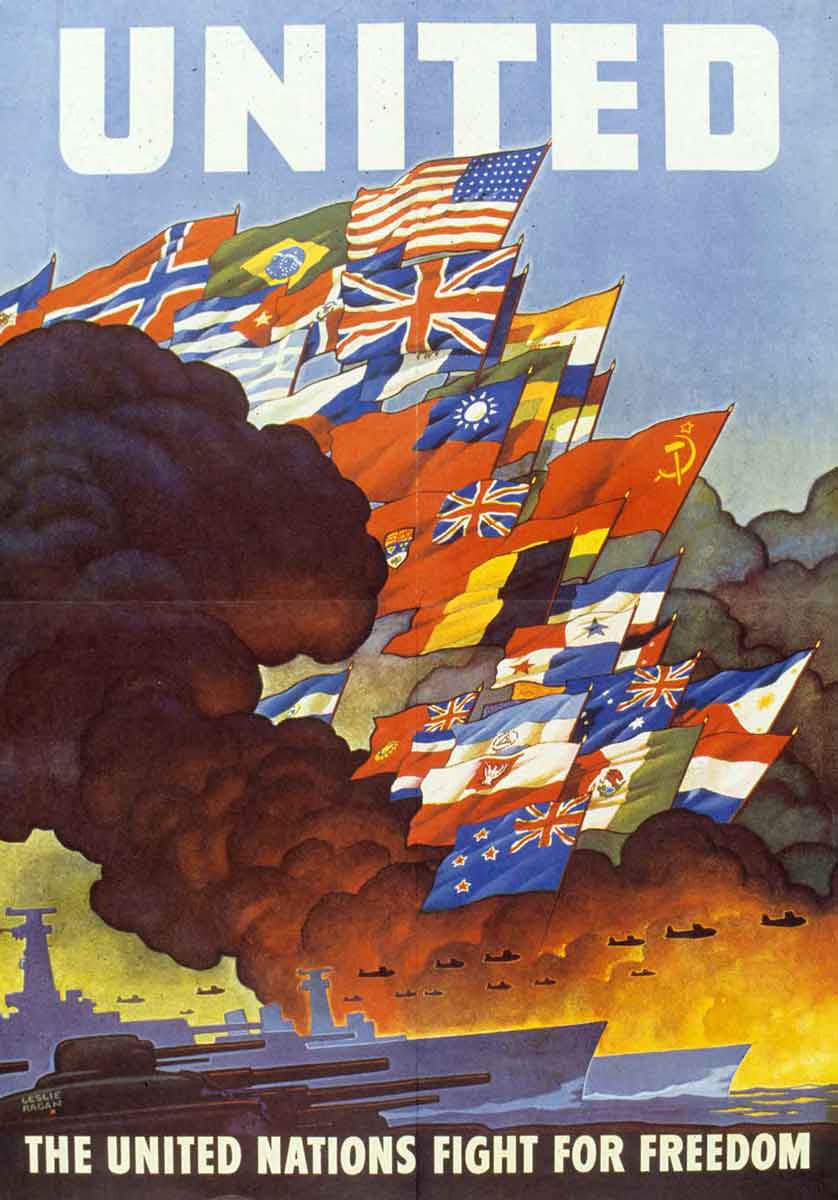

With its American lifeline, Britain hung on. But that didn’t change the facts on the ground. By February, 1941, Nazi Germany looked invincible in Europe while Japan’s steady expansion into China and elsewhere in Asia continued apace. It seemed certain the world’s future would be dominated by fascism or communism or both. Freedom’s only hope was to hunker down in America behind the mighty defensive walls of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

That was when Henry Luce wrote one of the most famous editorials in American history. He published it in Life.

It begins:

We Americans are unhappy. We are not happy about America. We are not happy about ourselves in relation to America. We are nervous — or gloomy — or apathetic.

It’s an opening worthy of Eeyore but it worked because it was true. And Luce contrasted America’s anxiety with the feeling Great Britain.

The British are calm in their spirit not because they have nothing to worry about but because they are fighting for their lives. They have made that decision. And they have no further choice. All their mistakes of the past 20 years, all the stupidities and failures that they have shared with the rest of the democratic world, are now of the past. They can forget them because they are faced with a supreme task – defending, yard by yard, their island home.

With us it is different. We do not have to face any attack tomorrow or the next day. Yet we are faced with something almost as difficult. We are faced with great decisions.

Luce is setting up for something bigger than a call to support Britain. Or even to enter the war.

Plot spoiler: Luce wants Americans to accept that they’re already in the war, get serious about winning it, and then — the real purpose of the essay — lead the peace that will follow.

He starts the next section with a reminder:

We know how lucky we are compared to all the rest of mankind. At least two-thirds of us are just plain rich compared to all the rest of the human family – rich in food, rich in clothes, rich in entertainment and amusement, rich in leisure, rich.

That was a bold statement in 1941, when the United States was still crawling out of the savage decade of depravation known as the Great Depression. Luce wasn’t wrong, however. Americans were rich relative to the rest of the world. But to tell Americans that, so bluntly, in 1941? This is the opposite of pandering populism.

When the essay was published, whether the US should be in the war or stay out was talked about obsessively. So Luce pulled a rhetorical sleight-of-hand. (All emphasis mine.)

We are in the war. All this talk about whether this or that might or might not get us into the war is wasted effort. We are, for a fact, in the war.

If there’s one place we Americans did not want to be, it was in the war. We didn’t want much to be in any kind of war but, if there was one kind of war we most of all didn’t want to be in, it was a European war. Yet, we’re in a war, as vicious and bad a war as ever struck this planet, and, along with being worldwide, a European war.

Of course, we are not technically at war, we are not painfully at war, and we may never have to experience the full hell that war can be. Nevertheless the simple statement stands: we are in the war. The irony is that Hitler knows it – and most Americans don’t. It may or may not be an advantage to continue diplomatic relations with Germany. But the fact that a German embassy still flourishes in Washington beautifully illustrates the whole mass of deceits and self-deceits in which we have been living.

Perhaps the best way to show ourselves that we are in the war is to consider how we can get out of it. Practically, there’s only one way to get out of it and that is by a German victory over England. If England should surrender soon, Germany and America would not start fighting the next day. So we would be out of the war. For a while. Except that Japan might then attack the South Seas and the Philippines. We could abandon the Philippines, abandon Australia and New Zealand, withdraw to Hawaii. And wait. We would be out of the war.

We say we don’t want to be in the war. We also say we want England to win. We want Hitler stopped – more than we want to stay out of the war. So, at the moment, we’re in.

…

Now why do we object so strongly to being in it?

There are lots of reasons. First, there is the profound and almost universal aversion to all war – to killing and being killed. But the reason which needs closest inspection, since it is one peculiar to this war and never felt about any previous war, is the fear that if we get into this war, it will be the end of our constitutional democracy. We are all acquainted with the fearful forecast – that some form of dictatorship is required to fight a modern war, that we will certainly go bankrupt, that in the process of war and its aftermath our economy will be largely socialized, that the politicians now in office will seize complete power and never yield it up, and that what with the whole trend toward collectivism, we shall end up in such a total national socialism that any faint semblances of our constitutional American democracy will be totally unrecognizable.

Today, we tend to think American internationalists of this era were Democrats, led by FDR, while Republicans were isolationists. The lines were much more scrambled than that: Henry Luce was a fierce internationalist. And a Republican.

And here he lets loose on the Democratic president.

We start into this war with huge Government debt, a vast bureaucracy and a whole generation of young people trained to look to the Government as the source of all life. The Party in power is the one which for long years has been most sympathetic to all manner of socialist doctrines and collectivist trends. The President of the United States has continually reached for more and more power, and he owes his continuation in office today to the coming of the war. Thus, the fear that the United States will be driven to a national socialism, as a result of cataclysmic circumstances and contrary to the free will of the American people, is an entirely justifiable fear.

…

Having now, with candor, examined our position, it is time to consider, to better purpose than would have been possible before, the larger issue which confronts us. Stated most simply, and in general terms, that issue is: What are we fighting for?

…

The big, important point to be made here is simply that the complete opportunity of leadership is ours. Like most great creative opportunities, it is an opportunity enveloped in stupendous difficulties and dangers. If we don’t want it, if we refuse to take it, the responsibility of refusal is also ours, and ours alone.

…

…And so we now come squarely and closely face to face with the issue which Americans hate most to face. It is that old, old issue with those old, old battered labels – the issue of Isolationism versus Internationalism.

We detest both words. We spit them at each other with the fury of hissing geese. We duck and dodge them.

Let us face that issue squarely now. If we face it squarely now – and if in facing it we take full and fearless account of therealities of our age – then we shall open the way, not necessarily to peace in our daily lives but to peace in our hearts.

Life is made up of joy and sorrow, of satisfactions and difficulties. In this time of trouble, we speak of troubles. There are many troubles. There are troubles in the field of philosophy, in faith and morals. There are troubles of home and family, of personal life. All are interrelated but we speak here especially of the troubles of national policy.

In the field of national policy, the fundamental trouble with America has been, and is, that whereas their nation became in the 20th Century the most powerful and the most vital nation in the world, nevertheless Americans were unable to accommodate themselves spiritually and practically to that fact. Hence they have failed to play their part as a world power – a failure which has had disastrous consequences for themselves and for all mankind. And the cure is this: to accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.

“For such purposes as we see fit” leaves entirely open the question of what our purposes may be or how we may appropriately achieve them. Emphatically, our only alternative to isolationism is not to undertake to police the whole world nor to impose democratic institutions on all mankind including the Dalai Lama and the good shepherds of Tibet.

America cannot be responsible for the good behavior of the entire world. But America is responsible, to herself as well as to history, for the world-environment in which she lives. Nothing can so vitally affect America’s environment as America’s own influence upon it, and therefore if America’s environment is unfavorable to the growth of American life, then America has nobody to blame so deeply as she must blame herself.

In its failure to grasp this relationship between America and America’s environment lies the moral and practical bankruptcy of any and all forms of isolationism. It is most unfortunate that this virus of isolationist sterility has so deeply infected an influential section of the Republican Party. For until the Republican Party can develop a vital philosophy and program for America’s initiative and activity as a world power, it will continue to cut itself off from any useful participation in this hour of history. And its participation is deeply needed for the shaping of the future of America and of the world.

But politically speaking, it is an equally serious fact that for seven years Franklin Roosevelt was, for all practical purposes, a complete isolationist. He was more of an isolationist than Herbert Hoover or Calvin Coolidge.

Fact check: mostly true. And a reminder that the ways things turn out in the long run often leads us to retroactively turn history into simplistic images — images that erase contradictions and turn highly contingent events into straight lines of iron inevitability.

The fact that Franklin Roosevelt has recently emerged as an emergency world leader should not obscure the fact that for seven years his policies ran absolutely counter to any possibility of effective American leadership in international co-operation. There is of course a justification which can be made for the President’s first two terms. It can be said, with reason, that great social reforms were necessary in order to bring democracy up-to-date in the greatest of democracies. But the fact is that Franklin Roosevelt failed to make American democracy work successfully on a narrow, materialistic and nationalistic basis. And under Franklin Roosevelt we ourselves have failed to make democracy work successfully. Our only chance now to make it work is in terms of a vital international economy and in terms of an international moral order.

This objective is Franklin Roosevelt’s great opportunity to justify his first two terms and to go down in history as the greatest rather than the last of American Presidents. Our job is to help in every way we can, for our sakes and our children’s sakes, to ensure that Franklin Roosevelt shall be justly hailed as America’s greatest President.

Without our help he cannot be our greatest President. With our help he can and will be. Under him and with his leadership we can make isolationism as dead an issue as slavery, and we can make a truly American internationalism something as natural to us in our time as the airplane or the radio.

Remember, Luce was a Republican highly critical of Roosevelt. And here he is saying that if Roosevelt gets this right, and is backed by the American people, he could become history’s greatest president. Nothing in this essay feels more alien to our time than this elevation of country above party.

In 1919 we had a golden opportunity, an opportunity unprecedented in all history, to assume the leadership of the world – a golden opportunity handed to us on the proverbial silver platter. We did not understand that opportunity.

Wilson mishandled it. We rejected it. The opportunity persisted. We bungled it in the 1920’s and in the confusions of the 1930’s we killed it.

To lead the world would never have been an easy task. To revive the hope of that lost opportunity makes the task now infinitely harder than it would have been before. Nevertheless, with the help of all of us, Roosevelt must succeed where Wilson failed.

The essay stops. A sub-hed appears: The 20th Century is the American Century

Consider the 20th Century. It is not only [ours] in the sense that we happen to live in it but ours also because it is America’s first century as a dominant power in the world. So far, this century of ours has been a profound and tragic disappointment. No other century has been so big with promise for human progress and happiness. And in no one century have so many men and women and children suffered such pain and anguish and bitter death.

Drop the first and last sentences of that paragraph and the whole thing could have been written today. And the way things are going, well, that last sentence may also fit in not too many years.

…any true conception of our world of the 20th Century must surely include a vivid awareness of at least these four propositions.

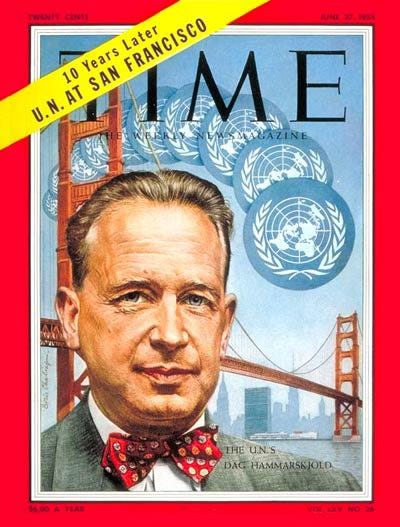

First: our world of 2,000,000,000 human beings is for the first time in history one world, fundamentally indivisible. Second: modern man hates war and feels intuitively that, in its present scale and frequency, it may even be fatal to his species. Third: our world, again for the first time in human history, is capable of producing all the material needs of the entire human family. Fourth: the world of the 20th Century, if it is to come to life in any nobility of health and vigor, must be to a significant degree an American Century.

As to the first and second: in postulating the indivisibility of the contemporary world, one does not necessarily imagine that anything like a world state – a parliament of men – must be brought about in this century. Nor need we assume that war can be abolished. All that it is necessary to feel – and to feel deeply – is that terrific forces of magnetic attraction and repulsion will operate as between every large group of human beings on this planet. Large sections of the human family may be effectively organized into opposition to each other. Tyrannies may require a large amount of living space. But Freedom requires and will require far greater living space than Tyranny. Peace cannot endure unless it prevails over a very large part of the world. Justice will come near to losing all meaning in the minds of men unless Justice can have approximately the same fundamental meanings in many lands and among many peoples.

As to the third point – the promise of adequate production for all mankind, the “more abundant life”– be it noted that this is characteristically an American promise. It is a promise easily made, here and elsewhere, by demagogues and proponents of all manner of slick schemes and “planned economies.” What we must insist on is that the abundant life is predicated on Freedom – on the Freedom which has created its possibility – on a vision of Freedom under Law. Without Freedom, there will be no abundant life. With Freedom, there can be. And finally there is the belief – shared let us remember by most men living– that the 20th Century must be to a significant degree an American Century.

This knowledge calls us to action now.

…

Once we cease to distract ourselves with lifeless arguments about isolationism, we shall be amazed to discover that there is already an immense American internationalism. American jazz, Hollywood movies, American slang, American machines and patented products, are in fact the only things that every community in the world, from Zanzibar to Hamburg, recognizes in common. Blindly, unintentionally, accidentally and really in spite of ourselves, we are already a world power in all the trivial ways – in very human ways. But there is a great deal more than that. America is already the intellectual, scientific and artistic capital of the world. Americans – Midwestern Americans – are today the least provincial people in the world. They have traveled the most and they know more about the world than the people of any other country. America’s worldwide experience in commerce is also far greater than most of us realize. Most important of all, we have that indefinable, unmistakable sign of leadership: prestige. And unlike the prestige of Rome or Genghis Khan or 19th Century England, American prestige throughout the world is faith in the good intentions as well as in the ultimate intelligence and ultimate strength of the whole American people. We have lost some of that prestige in the last few years. But most of it is still there.

This is an amazing paragraph. What Luce calls “prestige” is what, many decades later, political scientist Joseph Nye called “soft power” — the power of attraction as opposed to the power of coercion. The power that comes from being respected, admired and emulated. The power that comes from being a “shining city on the hill.”

As America enters dynamically upon the world scene, we need most of all to seek and to bring forth a vision of America as a world power which is authentically American and which can inspire us to live and work and fight with vigor and enthusiasm. And as we come now to the great test, it may yet turn out that in all our trials and tribulations of spirit during the first part of this century we as a people have been painfully apprehending the meaning of our time and now in this moment of testing there may come clear at last the vision which will guide us to the authentic creation of the 20th Century – our Century.

Consider four areas of life and thought in which we may seek to realize such a vision:

First, the economic. It is for America and for America alone to determine whether a system of free economic enterprise – an economic order compatible with freedom and progress – shall or shall not prevail in this century. We know perfectly well that there is not the slightest chance of anything faintly resembling a free economic system prevailing in this country if it prevails nowhere else. What then does America have to decide? Some few decisions are quite simple. For example: we have to decide whether or not we shall have for ourselves and our friends freedom of the seas – the right to go with our ships and our ocean-going airplanes where we wish, when we wish and as we wish. The vision of America as the principal guarantor of the freedom of the seas, the vision of America as the dynamic leader of world trade, has within it the possibilities of such enormous human progress as to stagger the imagination. Let us not be staggered by it. Let us rise to its tremendous possibilities. Our thinking of world trade today is on ridiculously small terms. For example, we think of Asia as being worth only a few hundred millions a year to us. Actually, in the decades to come Asia will be worth to us exactly zero – or else it will be worth to us four, five, ten billions of dollars a year. And the latter are the terms we must think in, or else confess a pitiful impotence.

Closely akin to the purely economic area and yet quite different from it, there is the picture of an America which will send out through the world its technical and artistic skills. Engineers, scientists, doctors, movie men, makers of entertainment, developers of airlines, builders of roads, teachers, educators. Throughout the world, these skills, this training, this leadership is needed and will be eagerly welcomed, if only we have the imagination to see it and the sincerity and good will to create the world of the 20th Century.

But now there is a third thing which our vision must immediately be concerned with. We must undertake now to be the Good Samaritan of the entire world. It is the manifest duty of this country to undertake to feed all the people of the world who as a result of this worldwide collapse of civilization are hungry and destitute – all of them, that is, whom we can from time to time reach consistently with a very tough attitude toward all hostile governments. For every dollar we spend on armaments, we should spend at least a dime in a gigantic effort to feed the world – and all the world should know that we have dedicated ourselves to this task. Every farmer in America should be encouraged to produce all the crops he can, and all that we cannot eat – and perhaps some of us could eat less – should forthwith be dispatched to the four quarters of the globe as a free gift, administered by a humanitarian army of Americans, to every man, woman and child on this earth who is really hungry.

But all this is not enough. All this will fail and none of it will happen unless our vision of America as a world power includes a passionate devotion to great American ideals. We have some things in this country which are infinitely precious and especially American – a love of freedom, a feeling for the equality of opportunity, a tradition of self-reliance and independence and also of co-operation. In addition to ideals and notions which are especially American, we are the inheritors of all the great principles of Western civilization – above all Justice, the love of Truth, the ideal of Charity. The other day Herbert Hoover said that America was fast becoming the sanctuary of the ideals of civilization. For the moment it may be enough to be the sanctuary of these ideals. But not for long. It now becomes our time to be the powerhouse from which the ideals spread throughout the world and do their mysterious work of lifting the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.

America as the dynamic center of ever-widening spheres of enterprise, America as the training center of the skillful servants of mankind, America as the Good Samaritan, really believing again that it is more blessed to give than to receive, and America as the powerhouse of the ideals of Freedom and Justice – out of these elements surely can be fashioned a vision of the 20th Century to which we can and will devote ourselves in joy and gladness and vigor and enthusiasm.

Other nations can survive simply because they have endured so long – sometimes with more and sometimes with less significance. But this nation, conceived in adventure and dedicated to the progress of man – this nation cannot truly endure unless there courses strongly through its veins from Maine to California the blood of purposes and enterprise and high resolve.

Throughout the 17th Century and the 18th Century and the 19th Century, this continent teemed with manifold projects andmagnificent purposes. Above them all and weaving them all together into the most exciting flag of all the world and of all history was the triumphal purpose of freedom.

It is in this spirit that all of us are called, each to his own measure of capacity, and each in the widest horizon of his vision, to create the first great American Century.

Henry Luce wrote those words ten months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and Hitler declared war on the United States. They were vindicated by the course of the war. But more than that, they were vindicated in the years and decades that followed, as the United States did so much of what Luce called for. America led and America thrived like never before. So did the world.

And today? The United States is wealthy beyond what even Henry Luce could have imagined. And yet it is inconceivable that any Republican — literally any Republican — would write something like “we must now undertake to be the Good Samaritan of the entire world” except perhaps as a mocking paraphrase of the views of people they despise.

Henry Luce’s essay thrums with a humane spirit and unbridled vision that are vanishing in modern America. In their place is the angry, resentful, paranoid mood of MAGA, a mood unnervingly similar to that which prevailed in 1920, when American turned its back on internationalism.

And some of the greatest tragedies in history followed. From those tragedies, Americans learned painful lessons. When the Second World War ended, they did the opposite of what they had done at the end of the First. They shouldered the mantle of leadership and built the international order that is the foundation of our modern world. But it seems those painful lessons have been now forgotten, somehow, and what was built by people like Henry Luce and Franklin Roosevelt is in danger of being destroyed by the likes of Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump.

We can only hope it doesn’t take a depression and a world war for Americans to learn again.

The stuff about trade with Asia was particularly presscient

My 22 year old non-political nephew recently asked me why I hate Trump (he has lots of UFC fan type mates who are big Trump fans, but me and his Dad have steered him on the right path, he was after arguments to use) and the arguments we gave him were basically what Luce was getting at here. That this western led world order for all its faults is a miracle, that the prosperity we live in is truly remarkable and not at all the kind of world 99.9999999% of humans have lived in, but that it is also incredibly fragile, that it was not built by accident and that it can be destroyed much easier than it can be maintained. That Trump is a destroyer not a builder and he is encouraging the rise of other destroyers and that to rebuild this once it is lost will be the work of generations and there is no guarantee that rebuilding will be the most powerful motivation of what comes after, that it is just as likely to be blame and beggar your neighbor policies. Also as you see in the UK with Brexit, the wreckers will never admit they wrecked it, they will find others to blame and the people who fell for the con will never admit they fell for the con and this will bring to the fore all sorts of terrible incentives (See Starmer not even mentioning Brexit now) that will make recovery so much more difficult, it it is even possible.

Thanks for this Dan. This paragraph “Henry Luce’s essay thrums with a humane spirit and unbridled vision that is vanishing in modern America. In its place is the angry, resentful, paranoid mood of MAGA, a mood unnervingly similar to that which prevailed in 1920, when American turned its back on internationalism” sums up the situation nicely. As a Canadian, I remember the time when America was a shining beacon, and somewhere that you wanted to go to succeed. I can’t imagine that being the case today. I mean Canada has its problems, but they pale into significance compared to the anger, negativity and inwardness one sees in America. Trump has successfully harvested that dark material and reaped his reward. I guess we can only wait to see how this all turns out, but I fear for the future: the world is not getting any nicer.