The Biden Team and the Bay of Pigs

How deluded can a small group of highly committed people become?

Should Joe Biden resign?

Much of the planet finds Donald Trump odious and frightening, and much of that portion of humanity has talked about nothing but that question since the disastrous debate Thursday night. I won’t add to that noise.

I wonder instead about the circle of senior advisors and party officials close to the president.

On Saturday, Peter Baker, The New York Times reporter, noted that The Times had spoken with “dozens” of those close to the president. None indicated there had ever been serious discussions about whether Biden should run again, or how, if he did, the campaign should deal with fears that his mental faculties were in precipitous decline.

If any of the president’s advisers has ever addressed Mr. Biden’s age with him in a forthright way, they have not acknowledged it. According to recent interviews with dozens of his closest aides and friends, the president engaged in no organized process outside of his family in deciding to run for a second term.

None of the advisers described a meeting or a memo that outlined pros and cons of a re-election campaign that might have addressed the consequences of age. None said they discouraged him from running or, for that matter, discussed how to address his age if he did. Instead, he simply told them to assume he was running unless he decided otherwise.

To me, that is damning.

It strains credulity to suggest that the confused and detached Biden we saw Thursday was a Biden the people close to him had never seen. But for the sake of argument, let’s say it was. And let’s stipulate further that everyone who works closely with Biden agreed previously, and in good faith, that he is up to the job. Even if both these conditions are met, the fact that they never sat down and seriously discussed a concern literally any reasonable person would have of any candidate Biden’s age — if only to discuss how to convince others of what they were themselves convinced of — is gobsmacking. That’s their job.

Then came the disaster Thursday night, the despair in anti-Trump circles, and the calls from a long list of surprising sources — including Matt Yglesias and The New York Times editorial board — for Joe Biden to step aside for the good of the country. (And the world, this Canadian hastily adds.)

So now will the senior people around Biden get serious and do their job? Early indications suggest they may stick to what they’ve said all along. Worries about Biden’s mental state are all Republican disinformation. Shame on the media for focusing on it. This is a blip. A hiccup. Nothing more. Get Joe in front of crowd and fire them up with a speech from a teleprompter. Nothing to see here. Everything’s fine.

But let’s be fair. If there are shifts in thinking underway, and Biden’s aides finally realize how dire the situation is, it will take time for that to percolate in discussions and turn into decisions. That’s particularly true if Biden himself realizes he’s done. It would be irresponsible to simply resign. It will take time to work out the best way forward, turn that into a plan, and implement it. So I don’t think anybody can yet be sure how Biden and his team will react.

But Peter Baker gives readers reason to think Biden’s team will stick with the status quo.

In sharp contrast to Donald Trump, whose one-sided demands for loyalty routinely turns staff and followers into embittered opponents, Joe Biden is loved by the people who work for him. They stick around for years. Even decades. He is a fatherly figure to them. And it’s much easier to rationalize slips and failings than tell your beloved father it’s time to go. Can their rationalizations extend even to Thursday night’s catastrophe? We’ll see. But one of my central maxims in life is that clever people can rationalize anything if they are sufficiently determined.

I think another factor may also be at work. It, too, suggests Biden’s people will refuse to budge.

“Groupthink” is a term that can be traced back to the 1972 book Victims of Groupthink. In it, the psychologist Irving Janis illustrated just how badly groupthink can skew judgment with an infamous story drawn from what was then recent history.

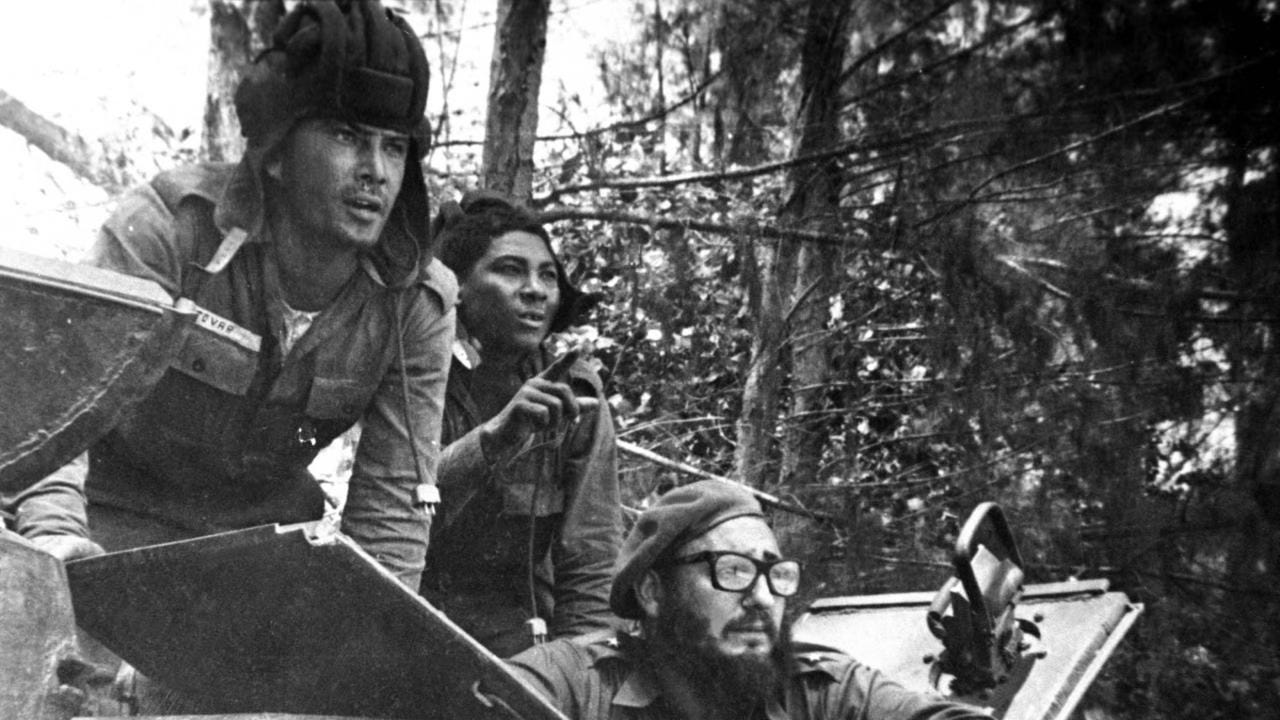

In the late 1950s, Fidel Castro’s rebels overthrew the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Castro wasn’t yet a Communist and his government was quickly recognized as legitimate by the United States. But Castro was a leftist reformer who legalized the Communist Party and expropriated some corporate property from American corporations. American hostility grew. Castro cultivated ties with the Soviet Union, further angering the US government. In the election campaign of 1960, John F. Kennedy hammered the Eisenhower government and his opponent Richard Nixon — Ike’s vice-president — for allowing Communism to fester off the coast of Florida.

When Kennedy became president, the CIA showed him a plan it had been working on under Eisenhower: The CIA would gather military-age anti-Castro Cuban exiles and give them military training in the US and Panama, as well as a secret base in Guatemala. Once equipped and ready, the US would land these soldiers on the Cuban coastline. With CIA support, they would head inland and foment insurrection and guerrilla warfare.

The key to the plan was secrecy. No one could know the US had organized and backed the rebels. To the world, this had to look like a spontaneous uprising of the Cuban people against Castro.

JFK gave the green light. The selected invasion point was a place called the Bay of Pigs.

The invasion was one of history’s great fiascos. The rebels were slaughtered. Worse, for the CIA, American involvement was clear to all. The new Kennedy administration was humiliated.

The Bay of Pigs invasion failed for a long list of reasons, most of which were perfectly obvious before any ship set sail. Very simply, the plan was ridiculous. Asinine. Ludicrous. It is astonishing anyone ever thought it could work.

But there is one fact that staggers imagination.

Ten days before the invasion, a story appeared on the front page of The New York Times. The first sentence read:

For nearly nine months Cuban military forces dedicated to the overthrown of Premier Fidel Castro have been training in the United States as well as Central America.

That’s bad.

Remember, this was a plan that hinged on secrecy. Even if the rebels landed successfully and set up camps in the mountains, as planned, the whole thing would be ruined if anyone knew the US was behind it. And now it was on the front page of The New York Times.

You might think the officials in charge would say, “well, that’s it then. Tell everyone to go home.” They did not.

Instead, while acknowledging the difficulties this posed, they somehow convinced themselves they could handle it and their super-secret plan could still go ahead. No one would be the wiser.

Were they idiots? No, they were top people in the CIA and the White House. So how did they convince themselves of something that was, on its face, laugh-out-loud implausible?

Irving Janis blamed what he dubbed “groupthink.”

These officials had worked together so closely for so long that they had inadvertently squeezed out dissent. They were all in agreement. Which is a wonderful feeling. After all, when you and all your peers agree, the very fact that you all agree feels like powerful evidence that you are right. Your confidence soars. You can’t all be wrong! Surely, glorious success will follow.

Groupthink is a force capable of rendering even brilliant minds blind to the screamingly obvious.

Reading Peter Baker’s reports, I smelled groupthink.

A small number of top people. A closed environment. Everyone dedicated to a cause. How could they not have gone over every argument about Biden’s capacity, every objection? And even if they had concluded that Biden could and should run, how could they not have seen the difficulties ahead and planned ferociously to overcome them? But then came Thursday night. Could they really still believe this was just a hiccup that would soon be forgotten? That the president could just read a few cleverly drafted lines on a teleprompter and move on? That seems impossible. Surely they couldn’t be so deluded.

But then, until it happened, it would have been inconceivable that White House officials would go ahead with a super-secret plan that must remain super-duper secret after that plan was published on the front page of The New York Times.

I hope I’m wrong. About all of this. I hope this is all the product of poor reporting or my misunderstanding or both. I hope everything works out, Joe gets the last laugh, and, sooner or later, enjoys the happy retirement he’s earned.

Otherwise, we could be facing a far worse fiasco, with incalculably worse consequences.

Every organization needs a “red team” which is a group of disrupters who actively work against groupthink. Sadly our current PMO does not believe in red teaming their brilliant ideas.

1) Groupthink, as I am sure you know, was a recognized problem long before it got its name. The Westminster Parliamentary System requires that there be a Loyal Opposition whose principal job is to find all the flaws in a government from an outsider's viewpoint. And the American Congressional System was designed to function without party affiliation so that consensus would occur out of diverse opinions.

Unfortunately, in many of today's governments' main decisions seem to be made within inner circles of people who are specifically chosen with loyalty to the leader as a main attribute (the PMO in Canada for example). These groups are incapable of making informed decisions because of their homogeneity. Thomas L. Friedman wrote an op ed in the New York Times (Dec 1, 2023) pointing out that Israel's invasion of Gaza was problematic for exactly this reason.

2) It dismays me that some responses to your article ignore your thesis and simply use the "Biden" stimulus to spout conspiracy theories, belief in which, ironically, demonstrate Groupthink almost as well as your article does.