A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about hindsight bias, how it makes the past look less uncertain and less scary than it was, and how this can make the present appear more uncertain and scarier than it is. (As always, bear in mind an important caveat about applying this perceptual bias: If you’re looking around and thinking things are unusually scary, that may be because things are unusually scary; or it may be the work of the uncertainty illusion; or some combination of the two.)

To illustrate, I asked you to nominate wonderful, carefree years in the past. I would then dig into the archives and find the fears we now belittle or forget altogether. First up was 1999.

People also suggested 1993 and 1994. And that made my happy for a specific reason.

Our minds crave the feeling of understanding when they think of the past (or anything else), and simple, clear stories deliver the feeling of understanding. “The 90s” is a perfect illustration. Say that phrase and people — those who lived through it and those who have only heard of it — will call to mind a simple, clear story in which the Cold War ended, the economy boomed and stocks soared. It was a “holiday from history,” to use a phrase coined when the 9/11 attacks appeared to have definitively brought that holiday to an end.

The problem with simple, clear stories is that reality is seldom simple and clear. Instead of simplicity, there is complexity, ambiguity, contradiction, and nuance. Instead of straight lines, there are zig zags, curves, and sudden turns. Take a closer look at “the 90s” and the mirage of our cartoonish perceptions dissolves. Even a brief examination is enough to see that “the 90s” is a silly label that encourages us to think there was no variation among those years, that they were all of a piece. But the early and late 1990s were dramatically different — especially in the United States.

Let’s start in 1993, then shift to 1994.

In 1993, Bill Clinton became president after defeating George H. W. Bush.

Take a look at this chart of Bush’s approval ratings:

This was a man who had an eighty-nine percent approval rating a year and a half before the election and was considered such a lock for re-election that Saturday Night Live had a skit about a Democratic debate in which the contenders fought to avoid being named the Democratic nominee. That no-win environment is how a little-known Southern governor named Bill Clinton got the nomination. But Bush’s approval rating crashed and Bill Clinton won. Why? The economy tanked. And Americans didn’t see it as some momentary setback. No, it was hard times. And things were going to get worse.

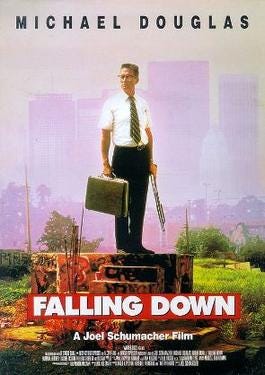

One of the big hits of 1993 was Falling Down, in which an ordinary guy snaps. It reflected the mood eerily well. As I wrote recently, it was a time when countless observers were sure America was becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of Japan Inc. and one of the big political books of the year was Bankruptcy 1995: The Coming Collapse of America and How to Stop It. Forget Cold War triumphalism. There was despair. And it was shared widely enough that it turned a hugely popular president into a one-termer.

But that was 1993. By 1994, the economy was surging. Did people worry much in this supposedly golden year?

Oh, yeah.

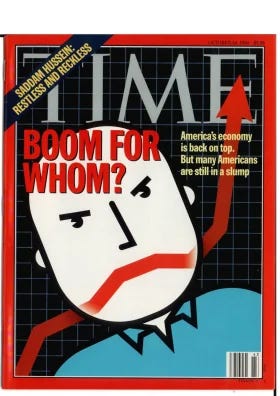

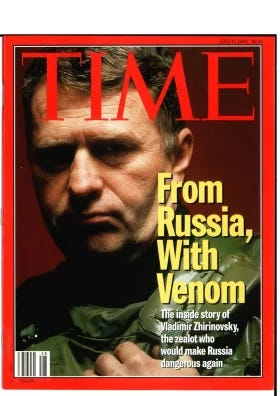

By objective measures, the economy was improving (in the US; Canada was a basket case until much later in the 1990s). But a lot of people didn’t feel it. Here’s the cover of Time on October 24, 1994.

The perception that things were not getting better was so widespread that general measures of optimism remained grim.

The level of optimism in 1994 was lower than it had been since the grinding recession of the early 1980s. It would only be lower in the white-knuckle years of the Great Recession and the painful recovery, as well as the annus horribili ushered in by 2020.

So was 1994 all sunshine and daisies? Not quite.

And I have to throw this one in for my Canadian readers: It’s the youth unemployment rate in Canada. See 1994? It was a horrible year. Believe me. I was an unemployed youth in 1994.

Fears were not limited to matters economic.

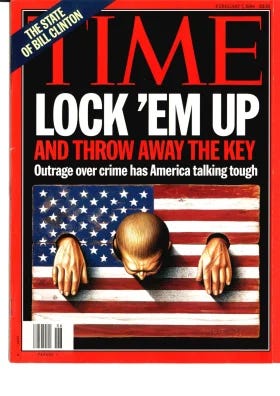

Violent crime rates rose through the late 1980s and early 1990s, in part due to the explosion of the crack cocaine trade, and there was a widespread belief — promoted even by some scientists and officials who should have known better — that a whole generation of so-called “crack babies” born with drug-induced defects meant carnage 15 or 20 years in the future. Worse, the number of youthful “superpredators” was going to soar in the 1990s. In fact, crime plunged dramatically and stayed low for the following quarter of a century — and terms like “crack baby” and “superpredator” were slowly and quietly forgotten.

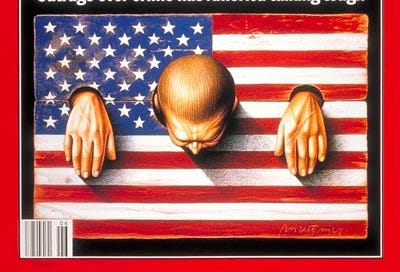

But how did people feel about crime in 1994? Criminologists know that if you ask people about crime in general, you get a more much more pessimistic take than if you ask about crime in the respondent’s neighbourhood. So I looked up the “in your neighbourhood” question and found that in 1994 worries about crime were even higher than they have been recently, following a large spike in crime.

The direct consequence of all that fear was the embrace of so-called “tough on crime” policies. Earlier in my career, I studied those policies. They aren’t actually tough on crime. They’re tough on criminals and their families. And because they cause the prison population to explode, they’re tough on government budgets. But they are not an effective way to reduce crime rates. (If you think the US crime drop in the late 1990s suggests otherwise, I invite you to compare Canadian data. Canada rejected tough on crime policies. Canada’s prison population didn’t soar. Yet Canada’s crime trends were all but identical with those in the US.)

So the economy is shaky. It’s carnage in the streets. Anything else?

Here’s another one that disappeared down the collective memory hole, along with “crack babies” and “superpredators.”

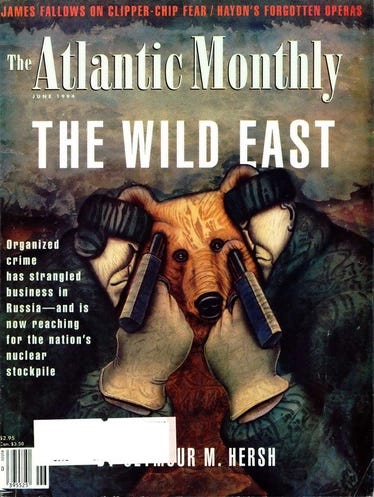

If the superpowers fighting a thermonuclear war was the classic fear of the early 1980s, the threat of nuclear weapons on the black market was the holy terror of the 1990s. “Suitcase nukes.” “Loose nukes.” These terms, so exotic today, were commonplace.

The big reason was Russia. After the Soviet Union fell, Russia fell to bits. Lunatics like Vladimir Zhirinosky — remember him? — threatened to come to power. Worse, the Russia military crumbled, and the news was filled with stories of Russian soldiers selling anything they could get their hands on to anyone with some cash. Some days it seemed anybody could buy a Russian nuke for $100 and a case of vodka.

As for the big-thinkers in the White House and on the Davos circuit, they had even worse nightmares keeping them awake.

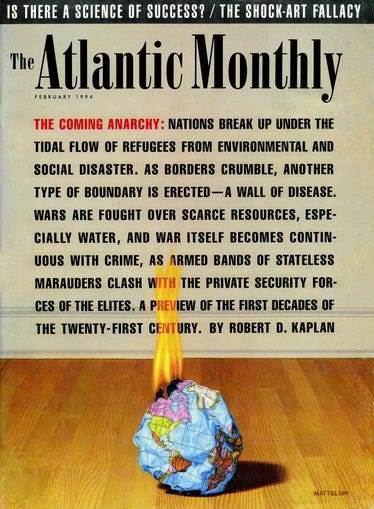

That cover of The Atlantic is self-explanatory. And terrifying. It had a huge effect. The author, Robert Kaplan, was invited to the White House. And he turned that story into a best-selling book.

And if that wasn’t enough to harsh your buzz, The Atlantic also had this warning for readers.

There was lots more people worried about in 1994 but I think the point is made.

It most definitely was not a holiday from history.

Yes, Dan I do remember the impact of the Kaplan article. I was working as a foreign service officer at the time and the policy “poets” were seized with dark thoughts of The Coming Anarchy and especially Kaplan’s thinking on the break up of North America along longitudinal lines (“Cascadia”) while also using the article to push for a foreign policy review.

Great article. The question, though, is whether we were worrying too much and those threats to our world weren't really that bad, as they didn't come to pass, or if instead those threats were as bad as they seemed then, but by calling them out and generating actions to counter them, we dodged the ball.

And then, maybe worrying today about current threats is the safe thing to do?