“Mister, we could use a man like Herbert Hoover again!”

That’s a line from the wistful duet that serves as the opening theme song of the 1970s sitcom All In The Family. Sung by the show’s lead characters, Edith and Archie Bunker, it made sense when the show premiered.

In the early 1970s, people in their sixties or older had personal memories of the Hoover presidency, while those in their forties or fifties would know at least a little about Herbert Hoover, from family, perhaps from school, or from occasional references in news or popular culture — references like the theme song of All in the Family.

Today, Herbert Hoover would never feature in the theme song of a show intended for a general audience.

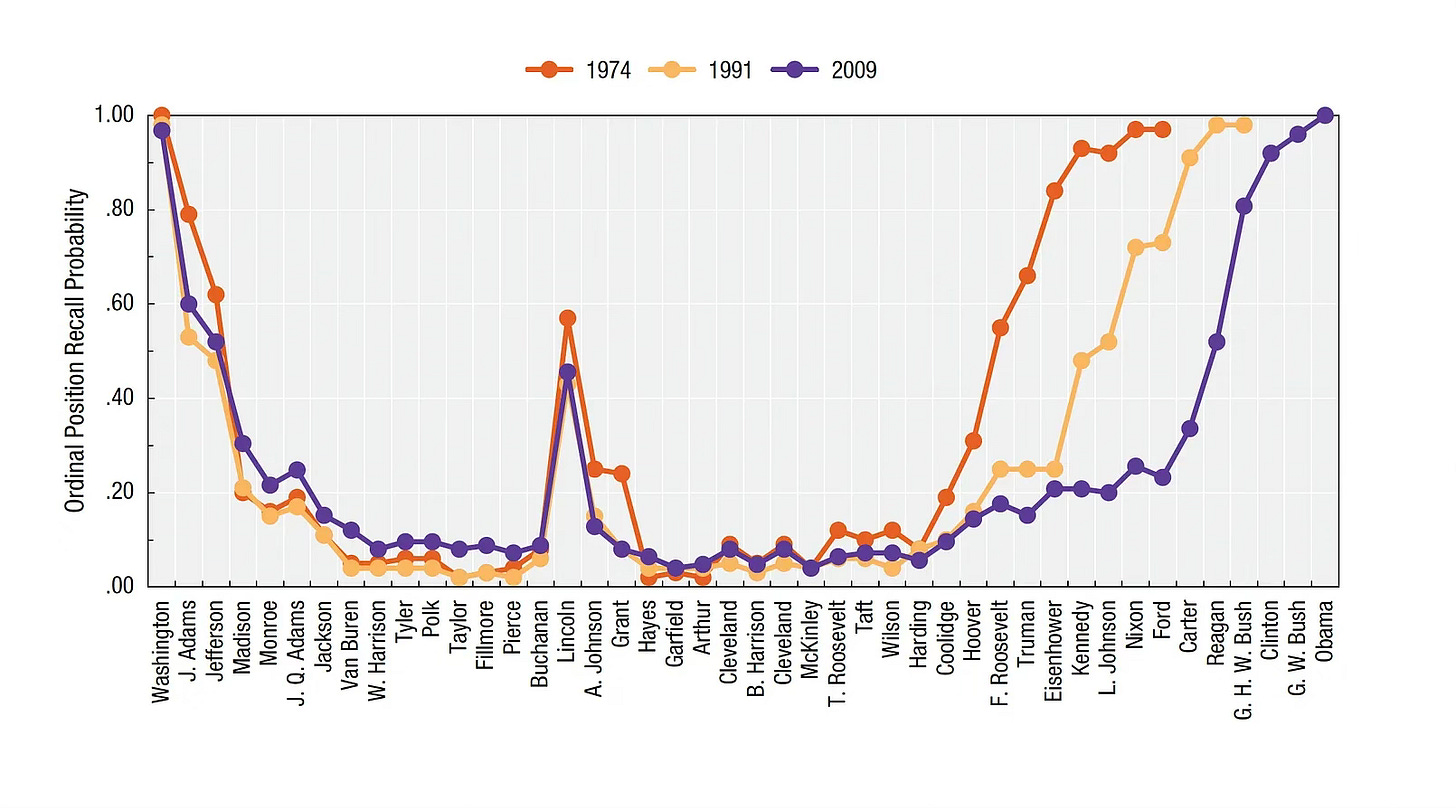

As shown by a brilliant survey first conducted the year All in the Family premiered, and repeated in 1991 and 2009, Americans’ ability to name old presidents declines on a startlingly smooth curve: In the early 1970s, Hoover had slid down that slope to a considerable extent but was still among the cluster of modern presidents known at least somewhat broadly. Today, he has joined Grover Cleveland and Millard Fillmore in the annals of the forgotten — sic transit gloria mundi — so it’s a safe bet that most people today wouldn’t know who Edith and Archie were pining for, or understand what that implied about their politics and worldview. Even the few nonagenarians in the audience would not have personal memories of the Hoover administration. (For that matter, most of the audience today wouldn’t have a clue who Edith and Archie Bunker were. Which is most disconcerting for this grey-haired Gen Xer.)

What we collectively remember and forget is a subject I find intensely interesting. I wish there were much more research like that survey of recall about past presidents. But as far as I know, there isn’t. Which compels me to speculate.

So if you will indulge me, here is my speculation: I suspect that the curved line traced by that survey indicates far more than presidential recall. I suspect, in fact, it traces something near-universal. It is the rate at which public memory of major events and milestones declines. And the bottom of the slope indicates something profound: That is the point where living, collective memory becomes history.

There’s a new show on Apple TV that may, inadvertently, provide a powerful illustration.

Masters of the Air is a miniseries about American bomber crews flying missions over Germany in the Second World War. It’s produced by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg and it has all the touches we expect of a Hanks and Spielberg production: Excellent acting, attention to period detail, startling realism, patriotism, and drama.

Ever heard of it? Good chance the answer is no. It hasn’t grabbed much attention, media, or audience. Which is telling, I think.

In 1998, newscaster Tom Brokaw published The Greatest Generation, an homage to the generation that fought the Second World War by a baby boomer born after that war. The book was an enormous bestseller.

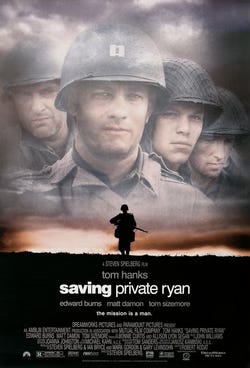

Saving Private Ryan was also released in 1998. Directed by Steven Spielberg, starring Tom Hanks, the movie’s depiction of the D-Day landings and the noble self-sacrifice of Tom Hanks’s saintly captain made for an instant classic.

Almost at the end of the century, the old men and women of the “greatest generation” were put under a spotlight and given a long standing ovation. The rhetoric about the “greatest generation” in media commentary was extravagant, and sometimes maudlin. It was also a little odd for a generation raised to be reserved and reticent. No doubt many found it embarrassing. But the rest of the population couldn’t get enough of it.

Three years later, the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers — produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks — was released. It, too, was an instant classic that garnered an enormous audience and a shower of praise.

In 2010, The Pacific — again produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks — was released. It was Band of Brothers in the Pacific theatre, but the response was much more muted.

In 2020, Tom Hanks wrote and starred in Greyhound, about a Second World War destroyer protecting a convoy crossing the U-boat infested waters of the North Atlantic. It sank with barely a cultural ripple.

Now it’s 2024. Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks are back with another story from the Greatest Generation’s fight to win the Second World War. And the response has mostly been a shrug.

So how can we explain this?

I’m going to take my own advice about cultural commentary and note that random distribution may always be at work in whatever pattern we observe. Maybe it’s just dumb luck that the earlier productions did well, while the later productions didn’t.

There’s also the fracturing of the audience. Big, shared cultural moments are harder to achieve in today’s balkanized media environment.

Quality is also a potential factor. Maybe the earlier productions were simply much better! But I don’t think that’s right. Take a look at Rotten Tomatoes. All the later productions received solid-to-excellent critical response. They just didn’t resonate with audiences.

And consider the other hand, to use my favourite cliche: In 1998, stories about a time when Americans united to fight tyranny would have had some inherent lustre, as they would at any time. But after 9/11 and a spate of squalid wars that ended in misery and failure, in a time when Americans are as or more divided and polarized than at any time since the 19th century, the appeal of feel-good patriotic stories about Americans fighting “the last good war” should be greater today than in 1998.

Maybe some of these factors are at work, in unquantifiable ways. But I think — I suspect — there’s something more fundamental at work.

In 1998, there were large numbers of veterans of the Second World War who were in their seventies or eighties. They were our fathers and mothers. Our grandparents. They were living memory.

In the final scene of Saving Private Ryan, the young soldier of the title morphs into an old man visiting a cemetery in Normandy. He breaks down and is comforted by his family. That is the past as living memory. It lives not only in the personal recollection of the old soldier. It lives for his children and grandchildren, too. His past is not his alone. It is theirs, too.

Today, Private Ryan would almost certainly be long dead. Very few veterans remain alive and almost all are centenarians — relics of a distant past, to be blunt, stored away and forgotten in old age homes.

I have some personal history with veterans of that age.

Way back in 1998, the golden year of “the greatest generation,” my newspaper sent me to France to write a series of articles. But not about the Second World War.

That year was the 80th anniversary of the end of the First World War. For the last time, the Canadian government sent veterans of la Grande Guerre back to France for commemorations at Arras, Vimy Ridge, and Mons. I met them there. The youngest was 98. Most were 100 or older. They were all frail shells, antiques from a world long vanished. One described how, as a junior officer on the staff of General Sir Arthur Currie, he had stood in the town square of Mons at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. Girls rushed up to give him a kiss. Men pressed drinks into his hand.

It was like speaking with a ghost.

I also recall how, when I told colleagues where I was going and why, they were astonished to hear there were any Great War veterans still alive. These men had long ceased to be alive in the memory of the wider community. They were, in a real sense, ghosts.

And I recall how the articles I wrote generated only modest response from readers. There were few letters to the editor. And the letters were abstract and impersonal. Unemotional.

I wasn’t surprised at the time. The war was generations removed. Awareness of those world-shaking events and the terrible toll taken on the generations that lived through it was low. I was asking readers to both learn unfamiliar history and connect emotionally with those who lived it. The first is a challenge. The second is far more difficult, and writers who do it successfully — think of Hillary Mantel writing about the court of Henry VIII — almost always deploy the techniques of fiction. To raise awareness of the history, I thought, was the most I could reasonably hope for with my short, factual newspaper articles.

But later that same year another staff writer published a similar series of articles, except his were about “the Greatest Generation.” The outpouring from readers was massive, personal, and emotional.

Why the discrepancy? I thought at the time the simplest explanation was likely the best: The other writer had done a much better job than I had.

I don’t think that today.

I now think that in 1998 there was a line between the generation that fought the Second World War and the generation, one step back, that fought the First World War. The veterans of the later war were part of living, collective memory, so younger generations could easily imagine and feel their stories. But the older veterans had crossed a profound line and joined all the veterans of earlier wars in the musty and seldom-visited halls of history.

A little more than a quarter-century has passed since then and the line has crept ahead with the passage of years— just as the line on that chart of presidential forgetting slowly but inexorably shifts. So stories of Second World War heroism no longer resonate as they once did. They’re not part of public memory. The young men in those stories have become ghosts, like their fathers before them.

They have crossed the line between memory and history.

American presidents are exceedingly rare.

For the four or eight years they are in office, they are universally recognized. Their words and deeds are watched carefully and discussed endlessly. They stir passions. They sometimes even give their names to whole eras — the “Eisenhower era,” the “Reagan era” — so they come to personify entire cultural, economic, and political periods. “Eisenhower” becomes synonymous with hula hoops and Elvis Presley. “Reagan” means Madonna, leg warmers, and Wall Streeters snorting cocaine. Nothing could be more resistant to collective forgetting than the names of presidents. So the fact that they are forgotten, and at such a steady, predictable rate, is significant.

World wars are similar, in a sense. The two we have had — so far — even lasted roughly as long as a presidency. But they, too, cross from memory into history. And that line seems to fall roughly where it does for the forgetting of presidents.

It is three generations.

Our grandparents fall on this side of the divide; our great-grandparents on another. Three generations seems to be the longest even presidents and world wars can live in collective memory.

There are exceptions, of course, as that chart of presidential forgetting shows. Lincoln and Washington live on, no doubt because their stories are constantly retold, not as history, but as living stories intended to teach something important about the United States in the present. Only a small percentage of Americans remembers Hoover, and a much smaller percentage, I am sure, can see him as a flesh-and-blood man. Unlike Washington and Lincoln, who live on.

But absent extraordinary collective effort, three generations seems to be the limit of shared memory. The fact that this span happens to be the range of generations most people in a stable community will personally experience, in the past as today, adds to the plausibility of my little hypothesis.

Bear in mind most of what we remember is much less prominent than presidents and world wars, and is therefore much more ephemeral. I’m sure Archie Bunker is further down the slope of forgetting than Richard Nixon.

The past doesn’t vanish after three generations, naturally, as we see in the fact that recall of old presidents never goes to zero. Even Millard Filmore can stir a flicker of recognition among rare individuals today. But after three generations, the past ceases to be shared around the campfire by older folk, so it will be known only by those who find and open musty books.

And even that small minority will not share in the welter of images and feelings the past inspires when it is living memory. It takes effort and imagination to develop a feeling for the past, a sense of it as a time when people like us felt what we feel. That means the line between memory and history is defined not only by bare awareness of the sort measured by those presidential recall studies. The line is defined by empathy.

A feeling for the past comes easily within living memory. But on the other side of the line, in history, it requires patient, mostly solitary cultivation. Few of us bother. So great-grandparents fade as they recede into the past.

We could bemoan this, I suppose, and struggle against it, but some degree of forgetting is as necessary and inevitable for the collective as it is for the individual. Like the rower in Fitzgerald’s metaphorical boat, we can pull hard as we like against the current but still we will be “borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Thanks Dan, an excellent article...again! My mind immediately went to the "rebirth" in authoritarian regimes across the world and the collective effort needed to vanquish fascism and its derivatives then... now generations ago. How does a new generation find its way through such a new battle, and where does leadership spring from when there is no memory to drive them?

I enjoyed this post. As an old, it brought back memories of when I was a child, and the old people I knew then: at Remembrance Day ceremonies in elementary school, seeing old veterans of the First World War, and even a few very old men who had served in the Boer War (which our parents were able to explain to us). For my own children the very old soldiers they met served in the Second World War, preserving the memory at least for a while...