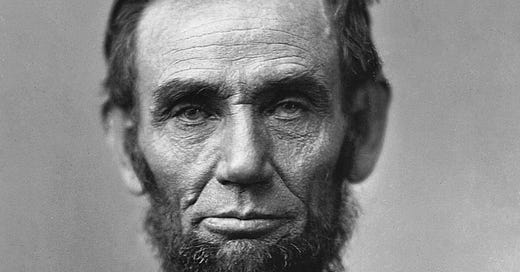

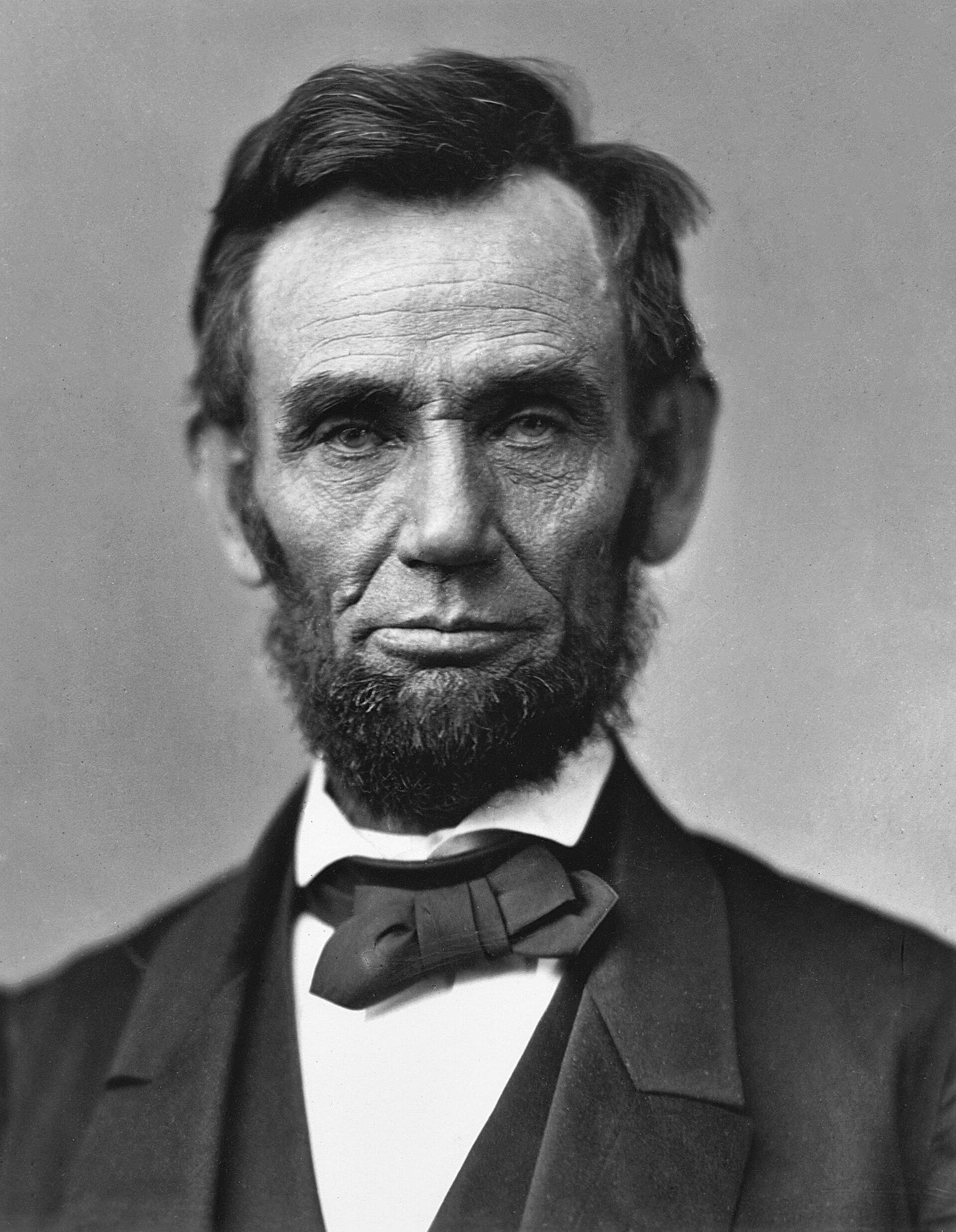

“You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do,” the President of the United States told a friend, “and unless some great change takes place, beaten badly.”

Who said that? And more importantly, when?

Maybe that sounds like Jimmy Carter in 1979 or 1980. Or George H. W. Bush in 1991. Both men had a touch of realism about them and enough humility to admit defeat when it leaned in close and glowered. Both did lose re-election.

But that wasn’t Carter or Bush.

It was Abraham Lincoln. In early 1864.

In November of 1864, Abraham Lincoln, the great emancipator, the man routinely named by historians the best American president, sought and won re-election. But in the first half of the year, Lincoln was sure he would lose. That wasn’t as odd as it sounds today. Most people were sure Lincoln would lose. They had good reason to believe that. Lincoln was widely despised, even within his own Republican Party, while pressure to negotiate peace with the secessionist South steadily grew.

Lincoln would lose. The United States as it was known would cease to exist. Every informed observer knew that. Even Lincoln.

There are many reasons to read history but, in my experience, the most important has been to correct humanity’s oldest folly, hubris, in two of its most noxious forms.

The first is simple: We think we know far more than we do.

You know the basic outline of the American Civil War, right? In November, 1860, Abraham Lincoln is elected president. Lincoln is the first Republican elected to the White House and the Republicans are a new party founded to oppose slavery. The Southern slave states secede. Things go badly for the Union until Robert E. Lee is defeated in July, 1863 at the epochal Battle of Gettysburg. Then — yadda, yadda, yadda — Grant accepts Lee’s surrender, the Union is saved.

That’s a lovely story arc: The war starts with high hopes, it goes badly, a watershed battle reverses fortune, victory. Very Hollywood. But it bears little relation to reality. In fact, after the glorious victory at Gettysburg, the Civil War became even more of a grinding, exhausting, appalling war of attrition. The North won victories. The South won victories. But the battle that really symbolized the nature of the war was The Wilderness, in which the newly promoted Ulysses Grant launched a major offensive to take the South’s capital in Richmond, Virginia. Over two days of fighting in May, 1864 — almost a year after Gettysburg — the Union suffered 17,500 casualties. The front lines didn’t budge. It was a preview of the First World War.

History seldom delivers straight lines and sweet story arcs. To study history — to really study it — is to quickly realize that however complicated and messy you think human affairs are, they are far more complicated and messy, and whatever simple story you have in your head is a child’s toy your brain has fabricated to give you the feeling that you understand the world. And keep you amused.

Consider that as late as July, 1864 — a little more than a year after Gettysburg — Southern troops threatened to take Washington DC until their advance was slowed at the Battle of Monocacy. So how would an ordinary American have experienced the preceding twelve months? It was an agonizing, brutal, grind. The war dragged on and on. Men were slaughtered in unimaginable numbers. When or how it would end — if it would end — was hard to imagine.

Now picture yourself an ordinary American in, say, Pennsylvania. What had Abraham Lincoln brought the people of the United States? Interminable butchery and suffering. And this man wants to be re-elected in November? To hell with him. To hell with the war. To much of the American public, a negotiated peace increasingly seemed the only way forward. And a negotiated peace meant the end of the Union.

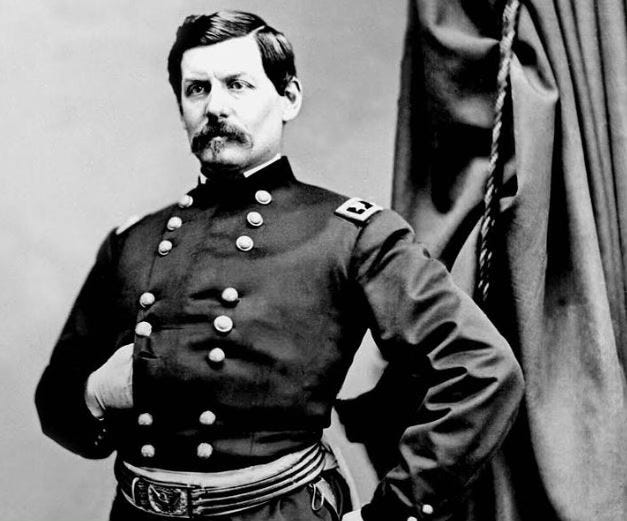

Most Americans who felt this way were Democrats. But the Democrats were themselves at each others’ throats, for another major faction in the party felt the North had to fight on, if only to achieve a better negotiated peace. They backed General George McClellan, whom Lincoln had sacked as the commander of Union forces. McClellan was a timid commander who should have been removed from command sooner than he was, but he was a handsome West Point graduate who looked good in a uniform and had an otherwise distinguished record. He had even been governor of New Jersey, so McClellan gave the Democrats a credible pro-war leader. The party paired that with a platform calling for a negotiated peace — and hoped the contradiction would appeal, not implode.

But the Republicans were also divided. Radical abolitionists saw Lincoln as weak and prevaricating. Many personally despised him. Some threatened to form their own party. Several of Lincoln’s top Cabinet members opposed his re-nomination. They were as sure as Lincoln that the president would not win.

Of course, this potted history is itself a gross simplification. But it serves, I think, to illustrate my point.

History: It’s more complicated than we think.

Which brings me to the second noxious manifestation of humanity’s hubris.

When I look into the future — a year or a decade or a century — I can’t help but feel I know where things are headed. Only broadly, of course. Only the general outlines, naturally. But, yes, I am confident I can see the shapes emerging from the fog. What factors will be important. How one thing will lead to another. How major events like presidential elections will turn out. My brain does this almost automatically, effortlessly, by assembling facts into stories, and stories into conclusions.

This is a human compulsion. We can no more stop ourselves from feeling that we know what is to come than we can stop generating explanations for the facts we observe in the present. We experience them the same way, too. When my brain offers an explanation for the facts I observe now, it does not say, “this is a reasonable hypothesis but there may be others.” It says, “this is the truth.” Similarly, when I expect the future to unfold some way, I don’t feel, “this is one way history could go but there are many others.” I feel that this is it. Period.

In 1864, Thurlow Weed, a heavyweight New York publisher and leading Republican politician, told William Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, that Lincoln’s re-election was “an impossibility.” That’s the intuitive brain talking. It likes to say things like “certain” and “impossible.”

There’s no way to dial down these intuitions about the future. But there is a way to catch and correct them. Or at least catch them and set them aside in favour of more thoughtful analysis.

Read history.

History is absolutely stuffed with smart, informed, confident men and women — people who know what’s coming — being gobsmacked when the future arrives. They include Abraham Lincoln and everybody else who thought Lincoln was doomed in 1864.

As it turned out, Republican hardliners did not break from the GOP. McClellan bungled the delicate balancing act between fighting the war and negotiating peace. And most importantly, the seemingly interminable war of attrition entered a new phase at exactly the moment Lincoln needed it to — when Atlanta fell at the beginning of September, 1864.

With everything breaking the president’s way, Lincoln won re-election by a comfortable margin. He had been on his way to becoming the last president of the United States. Instead, Lincoln became the greatest president of the United States.

Our judgements about the future — whether it’s a coming presidential election or the implications of AI or any of ten thousand other concerns — are wildly overconfident. That’s a sweeping statement, I know. There are exceptions. (See Superforecasting by Tetlock and Gardner.) But generally? Yeah, I’m comfortable with this: We know much less about the present than we think we do — and the gap between what we know and what we think we know is much, much greater when it comes to the future.

Humility is in order. Get comfortable with uncertainty. It’s not going anywhere.

In emotional terms, thinking this way can cut both ways.

Uncertainty is so unsettling that even the certainty of crashing to earth can be preferable to floating in the inky void of uncertainty. And when certainty is offered as assurance that some disaster will not come to pass, it’s brutal to have to say, “sorry, I will not partake.” In 2016, I could not share the confidence of the many smart, informed, confident men and women who were certain — certain! — that a two-bit New York grifter could never win the Republican nomination for the presidency, let alone the White House. I wish I could have. It would have made my 2016 more pleasant. And when he won, I wouldn’t have felt any more sick to my stomach.

But today? Polls favour the grifter’s return. Billionaires shower cash on the grifter’s campaign. The consequences of the grifter’s restoration grow more dire every time he talks about his plans for power. So as a man certain he is uncertain, how do I feel? I listen to the wailing and see the grim faces. And I smile.

They don’t know. I don’t know. Nobody knows.

So I shrug. And smile.

Can the Democrats hold together? I suspect so. Can Donald Trump be as incompetent as George McClellan? I’m quite confident of that. Can some happy surprise like the fall of Atlanta surface in September? Life is full of surprises, happy and otherwise.

Polls and money are worrying, yes. But there’s an ocean of time and possibility between now and election day.

If you find yourself huffing into a paper bag over the coming weeks and months, remember the sage words of America’s greatest president: “You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do, and unless some great change takes place, beaten badly.”

I write this as a Canadian, living in Canada, which has afforded me a seat to watch this American drama.

I recall vividly on election day in 2016 receiving an email from a relative who had emigrated to Ireland that "at least we won't have to listen to Trump anymore!" [Apparently many Trumpisms had made headlines in Ireland.] I emailed back that I did not know how the election would turn out but that the election - and the voters - was and were much more complicated than he appreciated and, well, neither he nor I could predict. And, of course, we couldn't; we were both surprised in a variety of ways.

Given that on the day of the election we could not predict, why on earth should we should we believe that we can predict five months out? Not one whole heck of a lot, that's what. And if "the deranged monster" should actually win? Or the "somnambulistic dementiated incumbent"? Again, we simply cannot predict with any possible certainty.

One prediction that I will stand by: it is a complicated world and pretty much anything can happen and likely will; perhaps good things, perhaps bad things, and usually impossible to sort good from bad for many, many years.

So, get a grip, sit down enjoy your coffee; accept humanity's hubris and read some history to realize that this too shall pass. To better or worse we cannot say.

But part of the point here is that most of the people prognosticating about Lincoln's likely defeat were in some sense correct at the time of their greatest pessimism--the thing is, something *happened* to change the momentum. There were several pivotal events that Lincoln himself could not fully control or anticipate that changed how his possible voters felt about him, about how his leadership was understood. Contingency IS important, and it isn't just about unexpected events or uncertain outcomes. People do change their minds for more subtle reasons, and sometimes the instruments we use to measure their likely actions are badly flawed to begin with. You and I both are skeptical about the entire apparatus of futurism, even in these ordinary kinds of prognostications by people involved in a particular situation or circumstance. But the problem is that the reminder of uncertainty extends in all directions. For example, it might be that if Biden were to suddenly announce he was throwing the convention open and would not be running, that this would be the equivalent of Grant and Sherman's victories. Or Trump's VP choice might shift everything dramatically away from him. And so on.

The challenge for leaders--what we hope from them--is that they not leave *everything* to chance, or that they don't just sit back and say "well, this might turn out well". There's a version of the Serenity Prayer that most of us look for--to change what can be changed and accept what can't be, to set *agency* against contingency. None of us want to live in a world where there's no leverage at all against uncertainty, where the future is infinitely indeterminate. I think we all hunger for leadership that does more than accept that there are still possibilities. Lincoln, after all, despite his pessimism about his own prospects, put Grant and Sherman into command precisely because he understood that McClelland and Burnside were not going to fight the war as it needed to be fought. (And that's why the Wilderness was a victory and understood by soldiers and observers as such--Grant didn't retreat but kept moving south, because he knew he had men and materiel to spare and Lee didn't.) So Lincoln did not wait passively for his uncertain fate to be resolve: he acted.