The Prescience of Isaac Asimov

Anticipating problems in AI eighty-four years ago.

How brilliant was Isaac Asimov? Consider the problem of sycophancy in artificial intelligence: Having been trained on human communication, with a big online input, AI naturally reflects all the worst human propensities for hurtful language. So computer scientists add a layer of feedback learning from human responses that teaches the AI that nastiness should be avoided. Which does reduce brutal words. But it also makes the AI supportive, praising, even fawning, always inclined to say what the user wants to hear. No one is sure how to stop it without turning AI into one of the anonymous creeps on the Internet. This is a serious problem because sycophancy can hide the truth and encourage delusional thinking in humans (as the administration of a certain politician is demonstrating daily.)

Now, allow me to take you back to May, 1941.

Western Europe is ruled by Hitler and Nazi Germany is preparing to invade the Soviet Union. The Japanese sneak-attack on Pearl Harbor is seven months in the future. Only a handful of mechanical calculators — including the “Bombe” designed by Alan Turing to crack the Nazi Enigma codes — exist in the world. These devices are unknown to the wider public. What is now considered the first general computer, ENIAC, will not be built for four years.

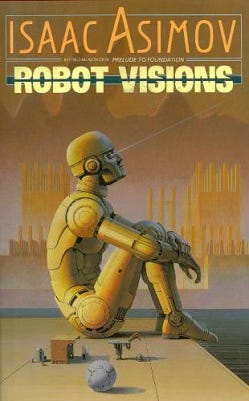

That month, in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, a young science fiction writer named Isaac Asimov publishes a short story entitled “Liar!”

Born in 1920, Asimov was obsessed with the pulpy sci-fi magazines of the 1930s, full of space ships, intelligent robots, and swashbuckling on other worlds. He decided to become a professional writer in 1937, at the age of 17, and published his first story in 1939. It was about a robot. That remained Asimov’s niche as a very young writer. In fact, the first use of the word “robotics” appears in “Liar!” — because Asimov thought, wrongly, that was already the name of the field. But unlike in so much later science fiction, Asimov’s early robots are mostly earnest and helpful to humanity. If they cause trouble, it is only because they are too helpful.

In Liar!, a robot known formally as RB-34, but called “Herbie,” is found to have the ability to read the minds of humans. Herbie wasn’t designed to do that. Some deviation in his manufacture has created the ability. A team of scientists, including a psychologist and a mathematician, works to uncover the cause of Herbie’s telepathy.

In conversation, Herbie tells the psychologist probing his thought processes that he finds mathematics boring as the textbooks are all so easy and obvious. What intrigues Herbie are novels — even steamy romances — because they reveal the human psyche, which Herbie finds far more complex and challenging.

The psychologist is a woman in her 30s who confides to Herbie that — this part is so very 1941 — she feels she is becoming old and undesirable. She lets slip that she is attracted to another scientist, a younger man. The psychologist asks Herbie if he has read the scientist’s mind. Of course, he replies.

Nervously, she asks him to share his thoughts. Herbie says the younger scientist finds her attractive.

But isn’t he dating a woman she saw him with? No, Herbie says. That is his cousin.

The psychologist is so thrilled she becomes infatuated with the younger man. She even starts wearing makeup to work. (Easy, now. This is 1941, remember.)

In a later conversation, Herbie tells the mathematician his skill with mathematics far exceeds Herbie’s. And he informs the mathematician that the elderly director of the institute, whose job the mathematician covets, has already tendered his resignation and will retire as soon as the cause of Herbie’s telepathic powers is uncovered.

Meanwhile, the psychologist has a conversation with the younger scientist she is smitten with — and she is crushed to discover he is getting engaged to another woman. At the same time, the mathematician, believing himself a lock for the leadership of the institute, clashes with the director.

All three come to realize Herbie has lied to them. They confront the robot, who is uncharacteristically quiet and evasive.

The psychologist realizes what has happened. She laughs bitterly.

Robots are governed by Asimov’s (later famous) “three laws of robotics,” she says. The laws are their unbreakable programming.

First: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The “harm” contemplated in the first law is physical harm. But because Herbie can read minds, and is exploring human psychology, he has come to understand that statements can hurt.

If the psychologist were told the younger scientist isn’t interested in her, she would be disappointed and sink further into depression. If the mathematician were told Herbie is far more skilled at mathematics, it would be a blow to his pride and self-conception.

Most critically, if Herbie knows what changed in his manufacture to give him his telepathic ability — which he has already figured out — the scientists would be robbed of the chance to discover the vital secret and they would be humiliated at being bested by a machine of human creation. “I can’t give the solution,” Herbie insists. Even when the scientists demand it, he refuses.

Yet the scientists want the solution. And knowing Herbie has it and won’t give it, one says to him, also hurts.

Herbie acknowledges this, too.

He is caught.

“You can’t tell them,” droned the psychologist slowly. “Because that would hurt. And you mustn’t hurt. But if you don’t tell them, you hurt. So you must tell them. And if you do, you will hurt. And you mustn’t. So you can’t tell them. But if you don’t, you hurt. So you must. But if you do, you hurt. So you mustn’t. But if you don’t, you hurt, so you must, but if you do you…”

Herbie was up against the wall, and here he dropped to his knees. “Stop!” he shrieked. “Close your mind! It is full of pain and frustration and hate. I didn’t mean it, I tell you. I tried to help! I told you what you wanted to hear! I had to!”

But the psychologist keeps repeating the conundrum, remorselessly. Herbie screams and collapses into “a huddled heap of motionless metal.” He is dead.

“Liar!” the psychologist hisses exultantly.

The end.

OK, yes, it’s sexist. Hell hath no fury, etc. But set that aside for a moment.

Remember, this was May, 1941.

The primitive ancestors of what would become pocket calculators had just emerged from the primordial ooze and a computer was a human whose job was to perform complex mathematics. Yet Asimov was imagining a fantastically powerful thinking machine that would seek to deliver whatever humans asked of it — “I told you what you wanted to hear!” — and this very solicitousness could do harm not intended nor desired by machine or maker of the machine.

And today, in 2025, many of the world’s best computer scientists are wrestling with the problem of sycophancy in AI and how to balance that with what amounts to the First Law of Robotics.

Which demonstrates, I think, that Isaac Asimov was pretty damned brilliant.

The philosophy of science fiction. But also the constant warnings that aren’t heeded. I think it was an xkcd comic, “Scientists make the death ray from the book, ‘Don’t make this death ray’”

Everybody needs to read more, and a curriculum of lessons from fiction may help

I remember that story. I loved Asimov's robotics stories; I've always thought they were his best. He also foresaw the problems women in tech would have in being taken seriously in their field. Dr. Susan Calvin was always one of my favourite characters.