"The Ugly American"

The history of a phrase tells us much about the collapse of US foreign policy

If one is of a certain vintage, the phrase “ugly American” has a vivid meaning.

Picture the worst stereotype of an American abroad. Loud, abrasive, arrogant. Incurious about local culture and politics because Americans have nothing to learn from foreigners. Incapable of delivering even a few words in another language and certain they can always make themselves understood by speaking English at a higher volume. Smugly confident that the United States is the most advanced of civilizations, in every way that matters, and all the rest of the world silently dreams of being American, or least meeting one of God’s chosen.

That’s an “ugly American.”

Curiously, though, that’s not what the phrase meant when it was coined. In fact, what it originally described was the opposite of all that.

The history of “ugly American” is worth reviewing because in that one phrase we can see how American foreign aid — and foreign policy more generally — is changing in the second Trump administration. There is even a direct connection between “ugly American” and today’s headlines, notably the hostile takeover of USAID by Elon Musk and his band of young zealots.

This isn’t a happy story, I’m afraid. But it is an important one.

In 1955, Graham Greene published The Quiet American, a novel describing the decline of French colonial Vietnam and growing American involvement. Greene, who was English, had been a foreign correspondent and he was unimpressed by the Americans he had met, finding them blinded by belief in American exceptionalism. A decade before American military involvement in Vietnam escalated to become a generational tragedy, Greene foresaw that America’s presence in Vietnam would not end well.

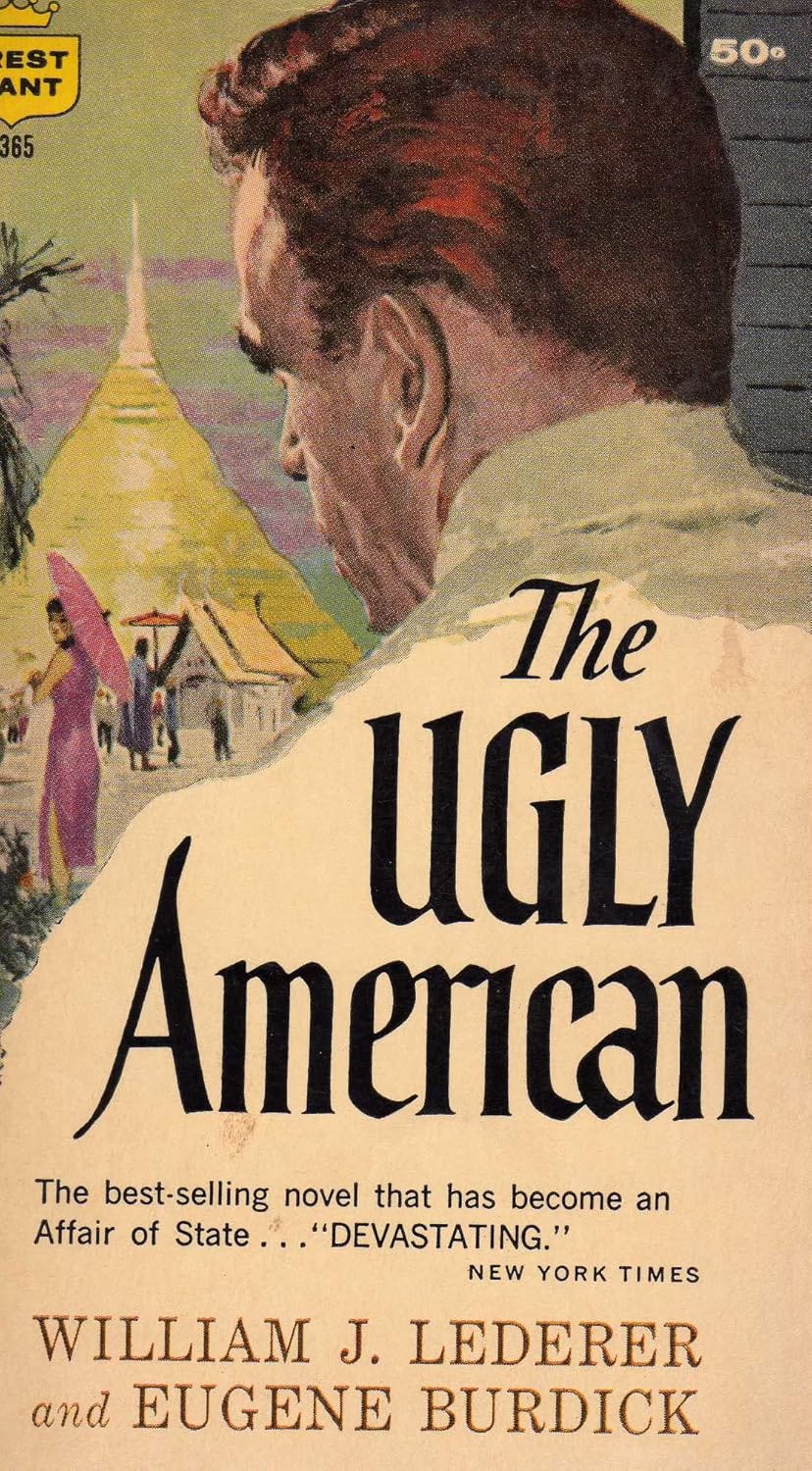

In 1958, another novel appeared — and it set off a political explosion like no novel before or since.

It bore the curious title of The Ugly American, which was clearly a play on Greene’s. The authors were Eugene Burdick and William Lederer. Both were veterans of the US Navy in the Second World War who had gone on to play various roles in south-east Asia. Both were furious with what they had seen.

But the phrase “the ugly American,” as used in the novel’s title, did not mean what it came to later.

The titular “ugly American” is the novel’s hero, an American engineer named Homer Atkins. Atkins is literally ugly. Unassuming. Not the sort of person who would ever turn heads. But he is also thoughtful, curious, kind, practical, and innovative. When he is sent to build dams and major infrastructure projects in “Sarkhan” — a south-east Asian nation representing South Vietnam — he learns that the people of Sarkhan need solutions to everyday poverty, not the grandiose, top-down development schemes he has been sent to deliver, so he urges the US government to change course. He is rebuffed. So he and his wife move into a Sarkhanese village, learn the language, and study the lives of the people around them. By patiently matching his Western education and skills with local needs, and by using only local resources, Atkins creates inventions that are sustainable, like a bicycle-powered water pump.

To Atkins, local problems require local solutions, and the only way to deliver those is to really understand locals. American arrogance simply won’t do.

“Why don’t you just send off to the States for a lot of hand pumps like they use on those little cars the men run up and down the railroads?” [his wife Emma] asked one day.

“Now, look, dammit, I’ve explained to you before,” Atkins said. “It’s got to be something they use out here. It’s no good if I go spending a hundred thousand dollars bringing in something. It has to be something right here, something the natives understand.”

Atkins makes a real difference. The Sarkhanese embrace him.

But only a few Americans are like Atkins and they don’t hold institutional power. Most Americans in the novel are like Louis Sears, a failed politician named ambassador to Sarkhan as a reward for loyal service to the party. Sears simply isn’t interested in Sarkhan. He doesn’t learn the language. He doesn’t study the culture.

Almost no one in the US embassy does. Instead, they all spend their days in a bubble of foreign service officers, military officers, journalists, and the high-ranking Sarkhanese officials who act as liaisons. These Americans are loud, arrogant, self-absorbed, and incurious. Why should they learn about the Sarkhanese? They are the advanced civilization. The Sarkhanese should learn about them. And be grateful for the opportunity.

These characters portray what the phrase “ugly American” came to mean.

In the form of a novel, Lederer and Burdick were making a policy argument — that the United States was doing foreign affairs in south-east Asia all wrong. Set aside smug superiority, they urged. Stop lecturing. Be curious. Learn. Be helpful. Make a real difference. That is how — to borrow a phrase from a later era — America will win hearts and minds.

And keep the Communists out.

The Ugly American was published in 1958, not long after the Soviet launch of Sputnik into space stunned Americans and especially the American political establishment. It had been an article of faith that American science and technology were the most advanced. That was suddenly in doubt. As was much more.

All around the world, poor, decolonizing countries where urgently trying to decide if the United States or the Soviet Union represented the superior form of government, and whether their country should side with the East or the West in the Cold War. The Americans and Soviets were furiously competing to win them over. Out of this contest would come the race to the moon, as America tried to salve the humiliation of being beaten into space by being the first to get to the moon and show that America was still the world’s technological leader.

The same dynamic created a much humbler contest — a contest to see who was better able to help new countries develop. Now here were Lederer and Burdick, who had lots of experience on the ground, saying the United States was falling behind just as it had in the space race. Worse, their novel depicted Soviet foreign service officers who were everything the Americans weren’t. They learned the local language. They lived among the locals. They were smart, dedicated to the mission, and didn’t look at Sarkhan as a dreary post they had to put up with until they could return home.

The Soviets were going to sweep south-east Asia, Lederer and Burdick were warning, not with armed force but persuasion. And the Americans had only their own arrogance to blame.

When The Ugly American was published, the entire American foreign policy establishment erupted. Many people and institutions were furious with Lederer and Burdick and accused them of various misrepresentations. But even the critics conceded they had crucial insights: Americans often were provincial and incurious. And it was ridiculous that they didn’t even learn the local language.

The controversy wasn’t limited to foreign policy circles, however. The Saturday Evening Post — the magazine of middle America — serialized the novel. The Ugly American became a huge bestseller, eventually selling more than four million copies.

A young senator by the name of John F. Kennedy was particularly taken with the novel. He bought copies to give to every one of his colleagues in the Senate.

When Kennedy became president in 1961, he created the Peace Corps to advance the vision of Lederer and Burdick. He also collected the various foreign aid programs developed under Dwight Eisenhower and consolidated them into a new agency called the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID.

That’s right. The same USAID Trump, Musk, and Musk’s minions are carving up without so much as a cursory policy review.

If you listen to Americans talk about “foreign aid” today, and USAID in particular, you will often hear them describe it, in effect, as charity. You will also hear them grossly exaggerate how much “charity” America gives the world. A poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans think, on average, that 36% of the federal budget goes to foreign aid. The real figure is less than 1%.

And that money is not charity. It has never been charity.

American foreign aid has always been intended to promote American soft power. Yes, it was put to work alleviating disease and promoting development. But in doing so, it was to win hearts and minds for America — and stop the Reds from winning those hearts and minds.

That has not changed. China has its own version of USAID doing similar work today. It also has foreign service officers all over the world telling local officials and ordinary people in developing countries that the Americans can’t help, or won’t, because they don’t care. China is your real friend.

So in some senses, little has changed between the era when The Ugly American was published and today. The great powers are contending for support in poor countries using foreign aid, development, and propaganda, as they always have. And “ugly Americans” of both varieties still very much exist.

There are thousands of Homer Atkinses — dedicated Americans who have devoted their lives to helping the poor in developing countries in the belief that their work is good for those countries and good for America.

And there are many, many more Louis Searses — smug, self-satisfied, incurious, certain they know what’s best and just as sure the poor of the world would all be better off if they did what Americans told them and showed a little more gratitude.

Elon Musk embodies that sort of ugly American. He knows everything about everything. He lectures people the world over. And asks no questions. Why would he when he knows everything? Late last year, someone on X, Musk’s platform, scrolled through US government databases and found someone whose job title was listed as “director, climate diversification.” Apparently thinking “diversification” meant the job had something to do with “diversity” — which is a synonym for “Marxism” in Muskworld — this person took a screenshot, with the job holder’s name and ID number and tweeted it. Musk retweeted this to his nearly quarter-billion followers along with the comment, “so many fake jobs.” What Musk didn’t know is this person’s job had nothing to do with DEI. She has science, engineering, and business degrees from MIT and Oxford, and her job, at relatively low pay, is to do highly technical work to make agriculture robust in the face of severe weather trends. No matter. Thirty-three million people saw Musk’s tweet and this person was subjected to such severe online harassment she had to lock down her online accounts and, in effect, go into hiding.

Because Elon Musk can’t be bothered to ask a question. Why would he? He already knows everything.

Musk is that sort of ugly American, indeed.

I would also say Donald Trump is that sort of ugly American, but that would be unfair to Louis Sears, who was arrogant and pigheaded but even he would have winced at Trump’s outright dismissal of all those “shithole countries.” Perhaps Trump and his ilk deserve a third, separate category. Let’s call it “ugliest Americans.”

That gets to the one thing that has changed, and changed massively, in recent years.

In the era of Eisenhower and Kennedy, both varieties of “ugly American” were internationalist because the belief that the United States should be engaged with the world, and should actively seek to win hearts and minds, was all but universal within the US government. The Homer Atkins-type ugly Americans were far better at the job than the Louis Sear-types, who were hopeless. But they at least shared an aspiration.

Today, we still have plenty of both varieties of “ugly Americans.” But the “ugliest Americans” are something new. Or rather, new at high levels of the US government. And new since the Second World War.

But not new in American history.

Go back before the Second World War and you find isolationists. They were arrogant and incurious but they mostly wanted to sit at home and ignore the world. Go back before the isolationists, however, and you get to the imperialists at the turn of the century.

The “ugliest Americans” are like the imperialists — deeply racist, profoundly incurious, and almost comically arrogant. Think William McKinley expressing his regret at having taken the Philippines from Spain because now, naturally, the United States could not hand it over to the little brown Filipinos, who were childlike and incapable of self-government. Hence, McKinley observed, “there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them and by God's grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died.” The Filipinos McKinley was “Christianizing” were Roman Catholic, by the way.

I feel a bit queasy comparing Donald “shithole countries” Trump with William McKinley, who, for all his clueless racism, expressed himself with polysyllabic panache. But the resemblance is undeniable, at least in this limited sense.

In 1958, Lederer and Burdick hoped American foreign aid would become humbler, more curious, more engaged with the world. It would be better for America and the world alike. But it now seems the long struggle between “ugly Americans” in the positive and original sense and “ugly Americans” in the negative sense is well and truly over. However many of the former are left, they are being fired and tossed aside even as you read this. All that will remain are the latter.

And overseeing them, the ones with the real power, will be the ugliest Americans.

Eugene Burdick died in 1965. William Lederer died in 2009. It’s probably just as well. Witnessing the return of American foreign policy to the 19th century would surely have killed them.

Dan, from the point of view of this American, in your capacity as a well-informed, fundamentally sympathetic, and appropriately critical Canadian observer, you continue to provide a valuable refreshing perspective on the madness convulsing your large neighbor to the south. Keep it up. We need it.

Reading your piece through the lens of my own experience (as a former US diplomat who served the final two decades of his career focused on South America), I recalled the IR theory of "Peripheral Realism" developed in that part of the world, mainly Argentina. Peripheral Realism describes the way in which relatively weak states on the "periphery" of global power navigate their constraints in pursuing their national interests, always mindful of the interests and whims and good or bad ideas of the behemoth to the north. For its part, Canada is cursed (or blessed, depending) by its location smack next to the center of global power: Ugly, in this case, America. Similarly constrained, but not peripheral. How to deal with that? Watching Justin Trudeau's news conference the other day, I couldn't imagine a more deft handling of that difficult spot.

As for the book you invoke, I had not thought about the Ugly American in these terms before, but it has been decades since I read it. It felt frankly OBE for different reasons. For one, Americans abroad in my experience had gotten a lot less ugly over time, sometimes behaving in model fashion relative to certain other (unnamed) nationalities. Also, ironically, considering the blind destructive unilateral approach of our current administration, the relative power of the US (by almost every measure) has declined. At the very least, we're entering a new era of geostrategic competition with a still rising PRC; more likely, centers of global power are multiplying and spreading outwards. US diplomats know they can no longer assume (if they ever foolishly did) that other countries will simply get in line. One reading of the Mad King Trump madness, in this context, is as the last bumptious gasp of an empire in decline, accelerated of course by the hubris and folly. Nice job.

We have also done a crappy job in explaining to the general public why foreign aid is provided. The idea that it is pure charity inevitably leads to many arguing that this charity ought to be first applied to those in need at home. Even making the soft power argument as you have done in this piece, Dan, clearly feels esoteric and unconvincing to many wondering how this benefits them in Arkansas or Saskatchewan. The same is true for diplomacy. There are some in our countries who will be supportive on a purely altruistic basis, feeling that it is their duty to assist others in need to the extent that they can. But they seem to be a minority, especially in hard economic times.

It is possible to take the next step to explain that existing in a world where there a fewer dictatorships, healthier and more prosperous countries in general benefits our countries as well. The current approach of the US government presents a good example as to how different the international order can be when based on trying to find win-win rather than “I win and you thus have to lose” scenarios. One might have thought that it was clear that helping prevent the spread of Ebola, HIV AIDS or COVID in other countries is to our benefit as well but we certainly have not been able to convince people on these principles.