Theatre of the Absurd

Remembering how the generation that fought it remembered the Second World War

Robert Clary, who played Corporal Louis LeBeau in Hogan’s Heroes, from 1965 to 1971, died last week. He was 96. Clary’s obituaries got me thinking about how perceptions of the past change because Clary was not only an actor in a cheesy American sitcom about Second World War prisoners in a German camp. He was a Jew. And a Holocaust survivor.

When Clary was sixteen years old, he and his mother were sent to a Nazi concentration camp for selection — where the skilled and the fit were chosen for slave labour while the rest were sent to die. His mother’s last words to him: “Do what they tell you to do. Tantrums won’t work anymore. I won’t be there to protect you.” Clary spent three years in camps. Near the end of the war, he was sent on a forced march — emaciated prisoners who failed to move quickly enough were shot — to Buchenwald, where he awoke one day to discover the guards were gone and George Patton’s Third Army had arrived. Clary’s parents and ten of his thirteen siblings were murdered by the Nazis.

Twenty years later, Clary was starring in a sitcom about a German POW camp.

Clary’s story was the most extreme, but he was far from unique in the cast of Hogan’s Heroes. Werner Klemperer, who played Colonel Klink, the ridiculous camp commandant, was the son of Otto Klemperer, a renowned symphony conductor. The Klemperers were German Jews, so in 1933, when the Nazis came to power, and Werner was 13 years old, they fled to the United States. John Banner (Sergeant Schultz, who knew and saw “nussing”) was Austrian Jew working as an actor in Switzerland when the Nazis occupied Austria, so he, too, emigrated to the United States. Several other recurring German roles on Hogan’s Heroes were played by Jews, including General Burkhalter (Leon Askin) and Major Hochstetter (Howard Caine).

It’s safe to say Hogan’s Heroes couldn’t be made today. It’s probably safe to say no one would even think of making it today.

As a rough estimate, I would say perceptions of the Third Reich and the Second World War transformed in the 1980s and 1990s. The former was increasingly seen not merely as a horrid dictatorship but as the ultimate secular expression of evil, while the latter was venerated as a sacred crusade to defeat that evil. That was new. And startlingly different from what preceded it.

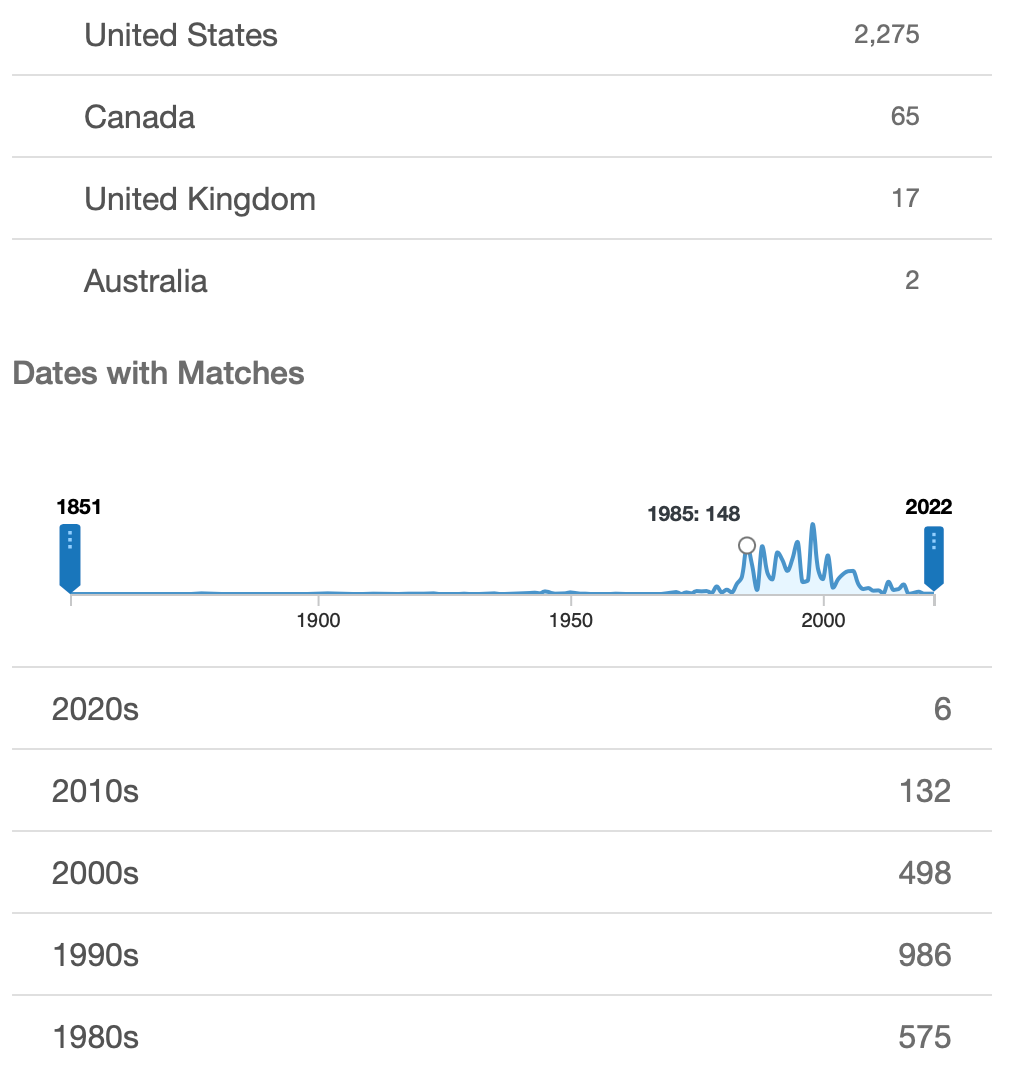

There are two phrases that really capture this shift. One is “the greatest generation.” Coined by Tom Brokaw in the title of his bestselling paean to the generation that fought the Second World War, it took off at the end of the 1990s and is still popular. Look at the chart below, from the Newspapers.com archive.

Or consider the phrase “the last good war.” For obvious reasons, it is particularly popular in the United States. And it really took off in the 1980s.

The Steven Spielberg movie Saving Private Ryan encapsulate the shift.

Whatever its other qualities, Saving Private Ryan is a relentlessly serious, almost worshipful movie, that depicts ordinary American soldiers as men called to a sacred task. In pursuit of that task, the soldiers suffer and die, and in the film’s final scene, director Steven Spielberg — an American, a Jew, and most importantly, a baby boomer — all but turns to the audience and demands, “are we worthy of their sacrifice?”

It is a humourless movie. One does not joke about the sacred.

The sense that the Second World War was a sacred struggle, that Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen were a close approximation of holy warriors, that the Nazis were the modern equivalent of Satan and his minions, has only grown since then. Video games and graphic novels that go to great lengths to provide historical accuracy increasingly erase swastikas on the armbands of Nazi uniforms or banners on walls — as if the swastika is the mark of the devil, possessed of demonic power, and must not be seen even in a video game where players gleefully mow down people who wear it.

The idea of joking about Nazis? Of portraying a camp commandant as an essentially harmless idiot? Presenting a German sergeant as a lovable lug who just wants to go home and make toys? Allied prisoners who are clever and successful, yes, but mostly wisecracking, back-slapping, cut-ups? Try pitching that to Netflix.

Hogan’s Heroes is admittedly an extreme example, but there are many others that underscore how perceptions have shifted.

Consider Catch-22, the 1961 Joseph Heller novel made into a Mike Nichols film in 1970. It’s about an American bomber crew flying missions over Nazi-occupied Europe, but their war looks nothing like a sacred cause and they in no way resemble holy warriors of “the greatest generation.” There is absurdity and irrationality. There is madness and crime. And there is a scathing, black sense of humour that mocks war — all war, even this one — as a ridiculous obscenity.

Or there’s Slaughterhouse-Five, whose subtitle says so much: It is The Children’s Crusade — a reference to the doomed effort of thousands of zealous children to march from Europe to the Holy Land in 1212. Allied soldiers are far from holy here, either, as they witness and participate in sheer madness, including the incineration of 25,000 German civilians in Dresden. For good measure, there is an alien abduction.

Slaughterhouse-Five was written by Kurt Vonnegut, who was an American infantryman in the Battle of the Bulge. Vonnegut was taken prisoner and was held in Dresden when the city was firebombed.

Catch-22 was written by Joseph Heller, who spent the war, like the protagonist of his novel, as a bombardier on a B-25. He flew sixty missions.

I’ve never come across interviews where either man was asked about the “greatest generation” hoopla but I’m confident both rejected it utterly. It’s the polar opposite of their writing, their worldview. Paul Fussell, a literary and cultural historian who served as an infantryman in the Second World War, expressed that view well in Doing Battle: The Making of a Skeptic, his 1996 memoir of the war. "My adolescent illusions,” he wrote, “fell away all at once, and I suddenly knew I was not and never would be in a world that was reasonable or just.” The last book Fussell published was not coincidentally entitled, The Boys' Crusade: The American Infantry in Northwestern Europe, 1944–45.

Unlike the worshipful Steven Spielberg (born 1946) and the devout Tom Brokaw (born 1940), these men had lived the reality. Their stories were profane, their appreciation of the ridiculous keen, and their sense of humour as black as jackboots.

So, yes, it was absurd that a man whose family was murdered by the Third Reich would play a peppy, beret-sporting French soldier — “oui, mon colonel!” — in a cheesy American sitcom set in the midst of the hell he endured for three years. Just look at this scene. Robert Clary survived a forced march to Buchenwald yet there he is, mugging for the camera, dressed as a German prison guard: Beneath that uniform, there is a concentration camp serial number tattooed on his skin.

Absurd, indeed. And why not? Life is absurd.

A vanishing generation understood that better than those that came after.