Three stories got a lot of attention this week.

There was Scott Adams’s racist, career-torching rant. The Department of Energy’s intelligence unit siding with the Covid lab-leak hypothesis. And a sad story in the Washington Post about a seemingly trivial altercation between a teacher and a girl wearing a hijab that spiralled into a debacle that has devastated everyone involved. (I’ll summarize each story for those unfamiliar with them.)

What I want to draw out is something simple but, I think, important: A key force at work in all these stories — and so many others — is the human aversion to uncertainty.

As discussed at length in Future Babble and Superforecasting, a sense of control is a fundamental psychological need. We can’t control what we don’t know. So we must know. It’s a compulsion. When we can’t satisfy it — when uncertainty is unmistakeable and unavoidable — we are unsettled, at a minimum. At worst, we are tormented.

Sophisticated interrogators know this. “The threat of coercion usually weakens or destroys resistance more effectively than coercion itself,” a leaked CIA manual stated. “The threat to inflict pain, for example, can trigger fears more damaging than the immediate sensation of pain…. Sustained long enough, a strong feeling of anything vague or unknown induces regression, whereas the materialization of the fear, the infliction of some sort of punishment, is likely to come as a relief.”

Anyone who has ever been through a cancer scare and had the dreaded possibility confirmed knows how true that is: Being told that “maybe” you have cancer and waiting for test results is so agonizing that when the doctor confirms you have cancer, you are likely to feel a strange sort of relief. “At least I know,” people always say.

“Maybe” is the cruellest word.

So how do we avoid uncertainty? By refusing to see it. Confronted by uncertainty, we can instead see fixed, firm facts, and proceed in the warm glow of certainty.

Which brings me to Scott Adams.

Die, Dilbert, Die!

In a lengthy video monologue, Adams, the creator of the wildly successful Dilbert comic strip, insisted that black people are “a hate group.”

Then, apparently determined to publicly kill Dilbert, Adams offered these sage words:

The best advice I could give to white people is to get the hell away from black people. Just get the f*** away… Because there’s no fixing this. You just have to escape. So that’s what I did. I went to a neighborhood where I have a very low black population.

Adams said lots more but that is the core of his argument. And success! Adams killed Dilbert.

There seems to be more going on in Adams’ thinking than conscious and expressed reasoning — I’m trying to be restrained here — but let’s stick to that and zero in on the basic question. How did Adams conclude black people constitute a “hate group?”

He cited some ancillary “evidence,” including videos of black people attacking non-black people. But Adams acknowledged that was merely “anecdotal.” (Adams has always made it clear he sees himself as a careful, rational thinker, unlike the fools and crazies who do not share his views. Because I am being restrained, remember, I will simply say I do not share Adams’s view of himself.)

The real basis of his claim — the only basis — is a single question in a single poll.

That was Adams’s first mistake. As the great Carl Sagan liked to say, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Basing a conclusion as extraordinary as Adams’s on the basis of a single question in a single poll is as reasonable as saying you know God exists because you saw Jesus’s face in burnt toast.

The survey in question was conducted recently by the polling firm Rasmussen.

Here is the exact wording of the question Adams found so compelling:

Do you agree or disagree with this statement: “It’s OK to be white.”

Slightly more than half of black respondents — 53% — said they agreed, while 47% said they disagreed.

It does not take unusual numeracy or analytical sophistication to see that these responses are almost evenly divided.

(CORRECTION: I somehow screwed up the numbers above. 53% did agree. But only 26% disagreed, while 21% of black respondents said they were unsure. Which makes Adams’s conclusions even more bewildering. Thanks to Paul Crowley for letting me know. And for anyone else who takes the time to help me catch and correct my inevitable mistakes.)

Even if we stipulate that agreeing with the statement is incontrovertible proof of racist hate — more on that in a moment — slightly more than half did not. But Adams didn’t say “an alarming proportion of black Americans expressed racist hate.” After first acknowledging that he was talking about less than half of black respondents, he went on to describe black Americans as a “hate group” and urged white Americans to treat them accordingly. To Adams, it seems black Americans are not 43 million individual people. They are a single amorphous blob. There’s a word for that way of thinking about people.

But it gets worse.

On its face, “it’s OK to be white” is a strange statement. What does “OK” mean in that context? Is it approval of what white people say and do today? Is it a statement about responsibility for past injustices by white people?

Or is it, as a literal reading would suggest, a statement that you don’t have anything against white people simply for being white? (But why would anyone even ask that?)

This matters because we want to know what the 47% of black respondents meant when they disagreed with the statement. If the statement is confused and confusing, then what people meant when they disagreed with must also be uncertain.

I think that’s perfectly obvious to any literate observer. I think any pollster would agree.

And I think Rasmussen should be ashamed. What they did is a textbook-worthy example of how not to write a poll question. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if it ended up in some textbooks.

But — at the risk of repeating myself — it gets worse.

As the Washington Post explained:

The phrase “it’s okay to be White” was popularized in 2017 as a trolling campaign meant to provoke liberals into condemning the statement and thus, the theory went, proving their own unreasonableness. White supremacists picked up on the trend, adding neo-Nazi language, websites or images to fliers with the phrase.

Any survey respondent who knew the backstory on “it’s OK to be white” might well react to the backstory, not the literal statement, and express disagreement not because they hate white people but because they know who has been using it and why. Which may explain why seven percent of white people also disagreed with the statement “it’s OK to be white.”

So the uncertainty inherent in the responses must be ratcheted up.

The obvious question now is whether Rasmussen — a conservative-friendly firm with a history of clickbait provocation — is incompetent or guilty of staging a deliberate stunt to be fed into the right-wing rage machine, earning them lots of free attention and heightened profile.

For its part, Rasmussen denied any wrong-doing.

“All we did was ask very simple questions that should be uncontroversial, and we are reporting on what Americans told us, nothing more,” Mitchell said in the video.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume Rasmussen had no idea that “it’s OK to be white” has been used in trolling campaigns and they really, sincerely thought they were asking “a very simple question that should be uncontroversial.” They just happened to land on that strange choice of words. By coincidence.

Sure. That could happen.

And let’s assume Scott Adams was similarly ignorant of the history of that phrase (a far more plausible claim).

We are still left with a horribly ambiguous poll question. Which means the responses are riddled with uncertainty.

And that should have been immediately obvious to any literate, good-faith observer.

But rather than acknowledge that uncertainty, Adams assumed there is only one possible interpretation of the statement — the literal reading — so anyone who disagreed with the statement could only have had that interpretation in mind. The worst interpretation.

Et voila! All uncertainty vanished. In its place, was a simple, clear “fact.” Black Americans are “a hate group.”

Of that, Adams was certain.

Before letting this go, I should note that while this case is extreme — to use British understatement — ambiguity in the meaning of survey responses is a common problem that pollsters typically sweep under a very lumpy rug.

Pollsters want to deliver what people want, and people do not want ambiguity and uncertainty. They want hard facts. Certainties. So that’s how pollsters routinely interpret their data. And in doing so, they mislead the public.

A simple illustration: Pollsters frequently ask Americans if the country is “on the right track” (or similar wording.) It’s a standard way of getting people’s general sense of how things are going. Seems reasonable enough, right?

But a funny thing happens to the “right track” results when control of the White House passes from one party to another.

They flip.

One day things are fine, the next day the United States of America is going to the dogs. Or the reverse.

Granted, who is in the White House should matter to how you feel about whether the country is on the right track. But to respond directly and literally and meaningfully to a question like that, a respondent would have to draw on so much more. What do you make of economic trends? Crime? National security? What’s happening in the culture? And so on down a very long list. These elements don’t instantly change the moment one president leaves the White House and another enters.

So what’s really going on here?

Daniel Kahneman dubbed it “attribute substitution.”

When we are asked a complex question that would require a great deal of careful analysis to answer — especially when we are asked by pollsters who deliver rapid-fire questions and expect rapid-fire responses in return — we routinely substitute a related but simpler question we can answer with an easy heuristic. We answer the easy question, not the hard one. But because this bait-and-switch happens automatically and unconsciously, we think we answered the complex and difficult question.

Imagine you’re the pollster. You ask me: “Do you think the United States is on the right track?”

Do I mentally work my way down the long list of relevant headings, giving each a subjective score, then aggregate those scores to produce a final answer? Of course not. And if I were the rare oddball who tried to do that, the pollster on the phone — whose pay depends on the volume of responses, not their thoughtfulness — would politely but firmly rush me along.

So instead I substitute a related but different question that I can quickly and easily answer: “How do I feel about the president?”

Boom. I know the answer to that instantly.

I give you my answer.

Now we both think I have answered the question you asked. But I didn't. Not really.

Then the poll data are released. How will pollsters, journalists, and pundits talk about these numbers? As literal and concrete responses to the specific questions asked, with only one meaning possible.

In other words, they will sweep away the ambiguity that is truly present in the data and treat the numbers instead as a set of cold, hard facts. And in doing so, they will replace uncertainty with certainty — as Scott Adams did, if much less egregiously and to much less offensive effect.

There is heaps more evidence like this, but it all comes down to something simple: Survey responses should always be treated with caution because what they say on their face and what people really think are commonly different to one degree or another.

This was, I hope, the last time I will ever write about Scott Adams. Now let’s move on to the second big story this week.

How confident are you?

From The New York Times:

New intelligence has prompted the Energy Department to conclude that an accidental laboratory leak in China most likely caused the coronavirus pandemic, though U.S. spy agencies remain divided over the origins of the virus, American officials said on Sunday.

The conclusion was a change from the department’s earlier position that it was undecided on how the virus emerged.

Covid is now so thoroughly politicized and polarized that the responses to this story were easily predictable.

Those on the right spiked the football and mocked the many ridiculously overconfident statements of their opponents who insisted that the lab-leak hypothesis was a conspiracy theory definitively debunked long ago. Those on the left insisted the story wasn’t really all that significant, that the Department of Energy was hardly the best judge, that most scientists still disagree, etc. It was, in other words, the usual festival of confirmation bias.

But it was also a powerful illustration of the allure of certainty.

In Superforecasting, Phil Tetlock and I argued that we have a natural tendency to use what Phil and I called a “three-setting mental dial.”

Yes. No. Maybe.

It is. It isn’t. Maybe

It will. It won’t. Maybe.

Certain. Impossible. Maybe.

Even that exaggerates the complexity of ordinary judgments because “maybe” isn’t equal to the other two settings. “Maybe” says “it is uncertain.” People loathe uncertainty so they loathe “maybe.” Circumstances may compel them to use “maybe” but they will go to considerable lengths to avoid it.

So our natural mental dial is closer to a two-setting dial, with a third setting we want to avoid whenever possible.

This is why, if a weather forecast says there is a 70% chance of showers and it doesn’t rain, people will typically say the forecast was wrong — even though the forecast said there is a 30% chance of no rain. That’s the two-setting mental dial at work. Any probability from zero to 49% becomes “it won’t rain” and probabilities from 51% up mean “it will rain.” Only a precise 50/50 split is treated as “maybe.” And woe betide the meteorologist who dares to say there is a 50% chance of showers.

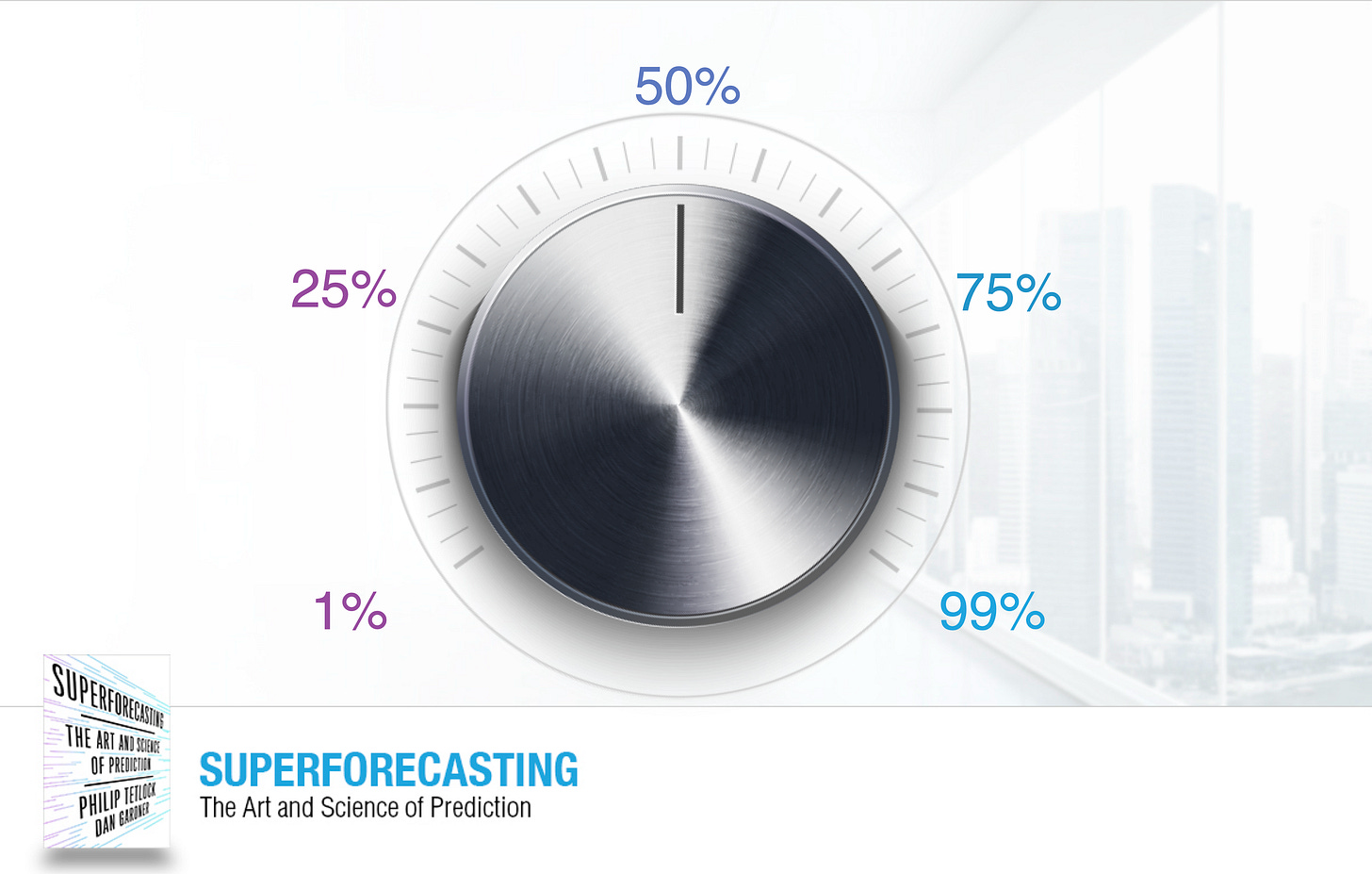

Following are some slides I use to visualize this in talks.

We start with the two-setting mental dial we are naturally inclined to use. On this dial, there is only certainty — either it will or it will not.

But sometimes reality confronts us with uncertainty that’s impossible to ignore. When that happens, we reluctantly add the third setting — “maybe.”

But there is a way to think that is radically (in the original sense of the word) different.

It starts with epistemic humility — an acknowledgement that flawed humans trying to grasp even a little of this complex reality never truly know anything with perfect certainty. Certainty is an alluring illusion, in this thinking. A mirage in the desert.

What follows from that? The two major settings on our dial have to go. Nothing is every truly 100%. And nothing is 0%.

That leaves only one setting. “Maybe.”

That isn’t helpful at all.

So let’s state this slightly differently: If we drop 100% and 0% from our thinking, everything becomes a question of degrees of uncertainty.

Or to put that numerically, accurate judgement is always about finding the right spot between 1% and 99%.

Now we are thinking in terms of probabilities.

But how many probability settings are there? The dial can be as fine-grained as you can manage. Just don’t indulge in false precision.

Maybe that means this.

Or maybe you can be as fine-grained as this.

Or even more fine-grained.

As Phil Tetlock’s research showed, superforecasters — people demonstrably excellent at making geo-political forecasts — tended to be astonishingly fine-grained. If they said something had an 83% chance of happening, that really meant 83%, not 80% or 85%. We know that because if their judgements were rounded up or down even that small amount, and their scores were recalculated, their accuracy declined. That’s meaningful precision.

Now let’s go back to that Department of Energy finding.

Here’s another paragraph from The New York Times.

Some officials briefed on the intelligence said that it was relatively weak and that the Energy Department’s conclusion was made with “low confidence,” suggesting its level of certainty was not high. While the department shared the information with other agencies, none of them changed their conclusions, officials said.

Officials would not disclose what the intelligence was. But many of the Energy Department’s insights come from its network of national laboratories, some of which conduct biological research, rather than more traditional forms of intelligence like spy networks or communications intercepts.

The people on the right who got excited about this story were too busy spiking the football to take much notice of that “low confidence” caveat.

But I don’t think the people on the left acquitted themselves much better. Yes, lots shouted “it’s only low confidence!” but finding a detail that allow you to dismiss unwelcome information is standard operating procedure for confirmation bias. Doubt that? Imagine the story had been reversed and the Department of Energy had changed its view from agnostic to “the lab-leak hypothesis is wrong.” Would people on the left have loudly and repeatedly shouted, “it’s only low confidence!”? (Would people on the right have ignored that caveat?) If you answer that question with anything other than “hell, no” you need to spend more time with humans.

What we saw this week was a lot of people judging the story with a two-setting mental model. And what they heard was something big and dramatic: Intelligence officials cranked the dial from “maybe” to “yes.”

But if we think about the story using the probabilistic approach — the approach that intelligence officials worth their salt use routinely — this story was a whole lot less dramatic.

The officials adjusted turned the dial a little to the right. But only a little.

Think of that probabilistic dial again. If 1% means it is almost certain Covid did not come from a lab leak and 99% means it is almost certain it did come from a lab leak, the Department of Energy officials may have turned their dial from, say, 47% to 53%. Or 40% to 60%.

That’s meaningful. But it’s not the dramatic plot twist it was seen as by so many people.

Now let’s add in all the other intelligence agencies in the US federal government which have looked into the lab-leak hypothesis.

From The New York Times:

In addition to the Energy Department, the F.B.I. has also concluded, with moderate confidence, that the virus first emerged accidentally from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a Chinese lab that worked on coronaviruses. Four other intelligence agencies and the National Intelligence Council have concluded, with low confidence, that the virus most likely emerged through natural transmission, the director of national intelligence’s office announced in October 2021.

Mr. Sullivan said those divisions remain.

“There is a variety of views in the intelligence community,” he said on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday. “Some elements of the intelligence community have reached conclusions on one side, some on the other. A number of them have said they just don’t have enough information to be sure.”

My guess? Put all those highly informed, thoughtful intelligence officials in a room and ask them to say what they think the probability of a lab-leak origin is and they are all going to land somewhere in the mushy middle.

Maybe the Department of Energy and the FBI are at 55% or 60%. Maybe some of the others are at 45% or 40%. But no one is going to be dramatically at odds with the others. The evidence is complex and mixed. And landing in the mushy middle is what probabilistic thinkers do when that’s the case.

Granted, this doesn’t make for good drama. It doesn’t lend itself to political fireworks.

But if you are more concerned with seeing reality clearly than grabbing attention and making noise, embracing uncertainty and thinking in terms of probability is essential.

What You See Is NOT All There Is

Finally, the saddest story of the three.

Tamar Herman knew that a Muslim girl in her second-grade class always wore a hijab. But one day, Herman thought she saw a hoodie covering it. She asked the girl to remove it, she says. Then, depending whom you believe, the teacher either “brushed back” the fabric or “forcibly removed it.”

“That’s my hijab!” the girl cried out, she told her mom later. Her hair was briefly exposed.

Herman says she apologized and assumed the incident would blow over. She was wrong.

What could have been a mistake followed by an apology became a maelstrom, driven by the parents’ ire, the teacher’s statements and by social media after an Olympic fencer, who had made international headlines for competing in her hijab, lit into Herman.

“This is a hate crime,” one person wrote in a local Facebook group. “You have to fire the teacher,” said another.

Within days, a Change.org called for Herman to be fired; it eventually collected more than 41,000 signatures. NBC News, USA Today and the New York Times carried the story far beyond this New Jersey suburb.

The local prosecutor opened an investigation. The school district toutedupcoming anti-bias training for the staff. “We are hopeful and all agree that the alleged actions of one employee should not condemn an entire community,” the superintendent said in another statement. Even the governor weighed in: “Deeply disturbed by these accusations,” Gov. Phil Murphy (D) wrote on Facebook.

More than a year later, Tamar Herman remains barred from the classroom, cut off from the calling and colleagues she loved. The school district is paying her not to teach. She is still terrified by threats from strangers on the internet, she says. Multiple lawsuits have been filed, and the issue has divided this suburban community along racial and religious lines.

But what actually happened that day, and why?

My take: Time after time in this little saga, people assumed the worst and without further investigation — even just speaking to the other person — they broadcast their conclusions to the world via social media. And time after time, this accelerated the downward spiral. The reputations of the main characters were gutted, their lives turned upside down. Everyone involved, however peripherally, feels beaten down and abused.

This story is presented, understandably, as a very modern cautionary tale. Social media can be terrifying.

But it’s also timeless, because the driving force is what Daniel Kahneman famously labelled “WYSIATI” — What You See Is All There Is.

WYSIATI is critical if we are to make the sort of snap judgements we so often had to make in the ancient environments in which our brains evolved. WYSIATI sweeps away a critical source of uncertainty — “is there more information I don’t know?” — and replaces it with certainty. Certainty enables snap judgments. Snap judgments enable quick, confident action.

But few of the important decisions most of us make today are of that sort. Withholding judgement until we learn more should be standard operating procedure. Call it WYSINATI — What You See Is Not All There Is.

But we’re not wired for WYSINATI. The human brain is “a machine for jumping to conclusions,” as Kahenman wrote. We are wired for WYSIATI.

Combine that Stone Age wiring with the technological ability to almost effortlessly broadcast any thought to the entire planet and … It’s not just the occasional unlucky teacher who is in deep trouble. It is our species.

Look, uncertainty is unsettling. I feel that as much as the next naked ape.

But if we’re to have a future, we have to change our relationship with it.

Maybe we can’t learn to love uncertainty. But we absolutely must learn to live with it.

Thank you for this interesting, thoughtful article. I agree with your criticism of Rasmussen. I don't believe with their statement that they thought their question, "should be uncontroversial.” They had to know this would result in divided results, and their use of the word "should" suggests bias by itself.

I also don't know why Adams would sabotage his career. Maybe he has plenty of money and decided to let his a long-hidden racist attitude out. I hope the public turns away from his work and gives him what he deserves.

Excellent article. The ironic thing is that being overly certain *looks* confident, but it can easily signify insecurity. But being able to admit "I don't know" or "I'm not sure" or "I need to learn more" often requires a different kind of confidence.