Wastelands and Progress

Ever climb a mountain? Lie on a beach? You are among history's elite.

While in Iceland recently, my host and I hiked a mountain just outside Reykjavik. It was mid-afternoon on a Wednesday in April and the mountain was as daunting, barren, and unpopulated as the whole island was before the first Viking landed in 874. But descending from the peak, we started to pass a steady stream of climbers. The workday had ended and Icelanders climb that mountain much the same way New Yorkers might take a stroll in Central Park after 5 PM.

My host and I — hello, Haukur — talked about Icelandic history. For most of the past 1,200 years, Icelanders clung to the rocky shores and survived by harvesting the sea. Inland, there were farms on pockets of good soil, but little else. Life on an Icelandic farm meant sod huts, backbreaking work, and, with a little luck, enough food to keep you and your children alive. There was no 5 PM mountain-climbing.

In fact, my host told me, even though spectacular mountains dot the landscape, and farms were seldom far from a thrilling climb, farmers might never hike up the rocky slopes to enjoy the gobsmacking views. (I can confirm that Iceland is as astonishing as you imagine. And then some.) This isn’t ancient Viking history, please note. Within living memory, farmers might go their whole lives without ever climbing the mountains they saw every day — because burning thousands of calories to climb a mountain for no reason other than the pleasure of exercise and glorious vistas is a luxury only the very rich can afford.

But today, Icelanders are very rich. So they climb mountains.

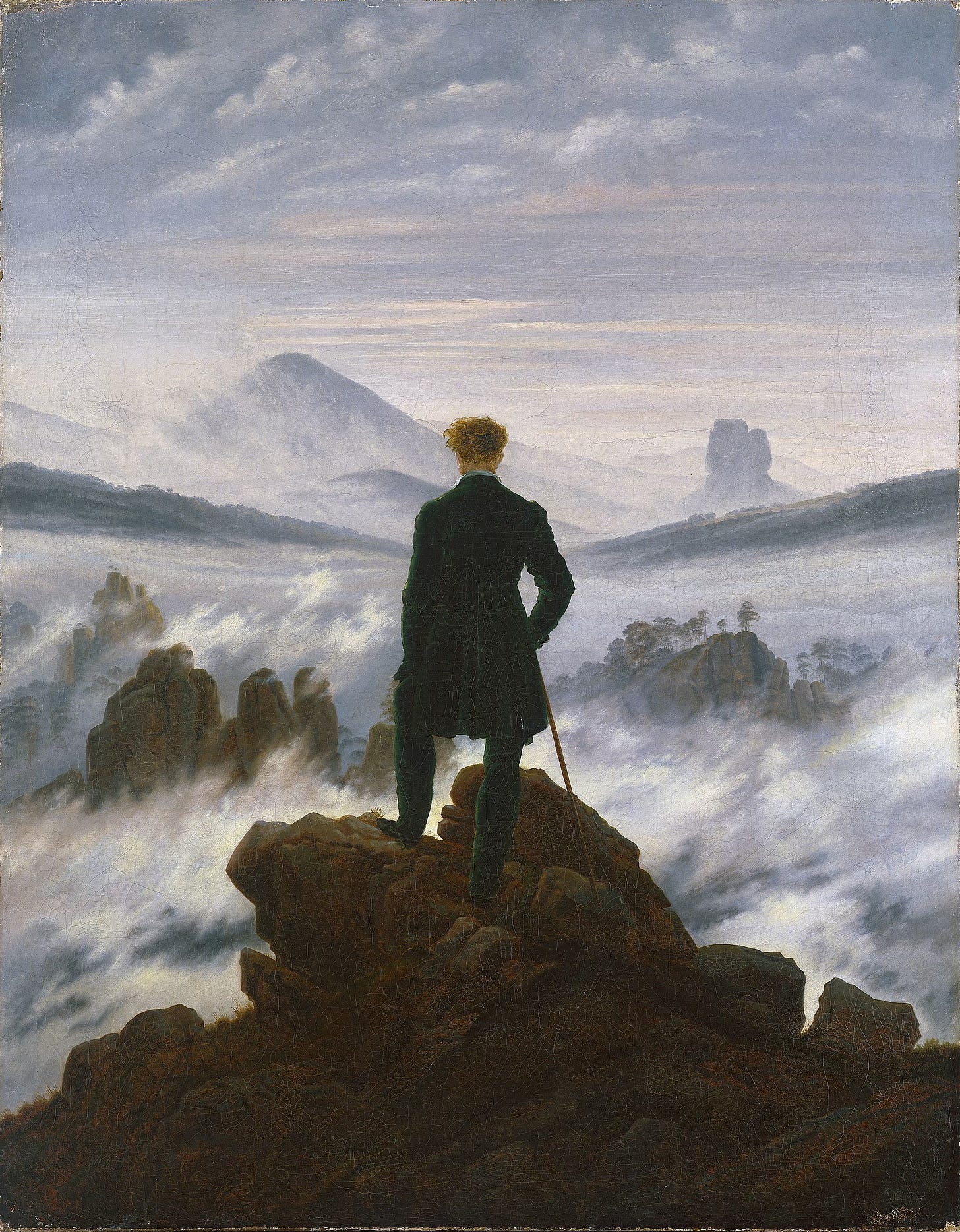

This transformation can be seen all over the world. In society after society, throughout history, mountains were daunting, barren places. There was little food to be had on their slopes so the vast majority of people never dreamed of climbing mountains. There were always exceptions, such as soldiers seeking glory or monks in search of extreme isolation. But only in the late 18th century did mountain climbing as we think of it really begin. And then, tellingly, it was a pursuit only for the wealthy.

Today, if you want to climb Mt. Everest, you must queue up.

That’s how rich we have become.

After Iceland, I went to Mexico.

And what does Mexico mean to the millions who flock there every year? A number of things. But at or near the top of the list are beaches.

Interestingly, the history of beaches is remarkably similar to that of mountains.

Beaches were wastelands through most of human history. There was often little food or other resources to be had on beaches. And they were dangerous. As places where boats could be launched or landed, people living near a beach were at risk of ocean-going pirates and slavers. Beaches were horrible places.

There were exceptions, of course. Very rich Romans built villas on or near beaches at the heart of the Empire. But that sort of thing was extremely rare. Throughout most of human history, beaches were avoided.

Today, of course, beaches are the most sought-after land on the planet for the same reason millions of people now climb mountains: We are so fantastically rich, historically speaking, that rather than obsessing over where our next meal will come from, we can bask in the sun and ogle the landscape. And thanks to the historically unprecedented levels of security that much of the world’s population enjoys, we can loll on a beach without worrying for a moment that we’ll be snatched by raiders and sold in some grotty slave market.

Yes, I know all about Mexico’s many and growing problems, particularly the awful levels of violence (whose ultimate origins lie in foolish American drug policies — but that’s an essay for another time.) Yes, I know there are billions still in poverty and they aren’t lolling on beaches. No, I am not saying everything is for the best in this, the best of all possible worlds. I am not a complete idiot. I promise.

If that last paragraph seems strange, please understand that literally every time I write about some improvement or other, a certain type of reader responds with hostility. “What about this injustice?! What about that hardship?!” And I have to say, “yes, all true. And important. But the improvement is true and important, too.”

Some things are better. Others are not.

Both those statements can be correct at the same time. Both thoughts can co-exist in the same mind. Honest.

Something to think about the next time you are puffing up a mountain or lying on a beach.

I’m going all Steven Pinker here, so I might as well close by going full metal Steven Pinker.

To contrast the barbarities of the past with the relative peace and prosperity enjoyed by so many in the present — please note the word “relative” and do not, I beg you, type the words “Pollyanna” or “Pangloss” in the comments below — Pinker has used many illustrations. But the one that has always stuck with me is the 16th-century French amusement of cat burning.

Yes, cat burning. As amusement.

As Pinker wrote:

In sixteenth-century Paris, a popular form of entertainment was cat-burning, in which a cat was hoisted in a sling on a stage and slowly lowered into a fire. According to historian Norman Davies, "[T]he spectators, including kings and queens, shrieked with laughter as the animals, howling with pain, were singed, roasted, and finally carbonized." Today, such sadism would be unthinkable in most of the world.

A recent story in The New York Times underscored the point.

A 7-year-old girl hawks cat-themed souvenirs in Flemish outside her parents’ shop. Two women in matching cat print dresses wander down a crowded street looking for a place to buy stuffed plush kitties. In every store and restaurant window, a cat figurine or statue signals allegiance to the feline persuasion.

This is Kattenstoet, Belgium’s cat-themed parade and festival.

Tucked among rolling farmland in the West Flanders region near the border with France, Ieper, Belgium, has not always had such an adoring relationship with cats. In the Middle Ages, when the city’s main industry was cloth making, they used cats to keep wool warehouses free of mice and other vermin. But when the felines began reproducing too quickly, town officials developed a ghastly solution: During the second week of Lent, on “Cat Wednesday,” cats were tossed to their deaths out of the belfry tower onto the town square below. At the time, the animals were seen as a symbol of witchcraft and evil, so their deaths were celebrated.

The last live cat was thrown in 1817, but Ieper (also called Ypres in French) developed Kattenstoet in 1937, a tradition to both acknowledge the city’s gruesome history and celebrate cats. The parade, which was held on Sunday, May 12, is filled with elaborate floats, costumes and performances. Afterward, a person dressed as a jester tosses stuffed animal cats from the belfry, down to the onlookers below.

Family entertainment then: torturing cats. Family entertainment now: adoring cats. Sure looks like progress to me.

Some people hate any mention of the “p” word but I don’t know how anyone hear stories like that — there are so many that whole books could be filled with them — and not conclude that moral progress is possible.

Not universal. Not inevitable. Not irreversible. Not untainted by other horrors. (Note that Ypres was the site of some of the most appalling battles of the First World War.)

Only possible.

Progress is possible: That’s a modest conclusion, in a sense, but also one of immense importance — particularly at a time when so many talk as if the elevator can only go down.

Mountains and beaches were also areas of extreme poverty in the past. Read Henry David Thoreau’s Cape Cod to see that Cape Cod was the poorest, most forgotten part of Massachusetts in the mid 19th century. Many of the people there used driftwood picked on the beach to heat their small homes and mixed seaweed with the poor soil to grow food.

Nice, I agree. Its also true that the wealth that we all enjoy came out of the ground in the form of oil, and it is the abundance of cheap and plentiful energy that has created all this material wealth. And the desire and ability to climb mountains and hang out on beaches. Especially for people who live in cold climates like Icelanders.

The longitudinal correlation between the rise of material standards of living and energy use (and hydrocarbon availability) is 1:1, because it actually causation.