Welcome to the Centrifugal Era

As mass media gives way to microculture, how will we keep talking and living together?

In May, 1961, a young lawyer named Newton Minow, then serving as chairman of the United States Federal Communications Commission, gave a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters. Speeches by bureaucrats at industry gatherings are routine. The reaction to this speech was decidedly not.

“When television is good, nothing -- not the theater, not the magazines or newspapers -- nothing is better,” Minow noted, citing The Twilight Zone and other shows. “But when television is bad, nothing is worse.”

I invite each of you to sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay there, for a day, without a book, without a magazine, without a newspaper, without a profit and loss sheet or a rating book to distract you. Keep your eyes glued to that set until the station signs off. I can assure you that what you will observe is a vast wasteland.

You will see a procession of game shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western bad men, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons.

And endlessly, commercials -- many screaming, cajoling, and offending.

And most of all, boredom. True, you'll see a few things you will enjoy. But they will be very, very few. And if you think I exaggerate, I only ask you to try it.

The phrase “a vast wasteland” was instantly famous. Or infamous, if you were a broadcaster. The television industry took revenge where it could. Most notoriously, the boat skippered by Alan Hale and crewed by Bob Denver and wrecked at the outset of the sitcom Gilligan’s Island was named the S.S. Minnow — in Newton Minow’s honour.

Like everyone over 50, I have a certain nostalgic fondness for Gilligan’s Island. But let us be frank among friends. That show was moronic. Naming the boat after the FCC chairman was less a riposte to Minow’s claim than exquisite confirmation.

As famous as Minow’s speech was, however, the observations he made were not remotely new. They even transcended television. Throughout the 20th century — even as far back as the late 19th century — observers worried that the production, distribution, and consumption of information and culture were changing just as profoundly, and in parallel with, the production, distribution, and consumption of manufactured goods.

Consider soap. Since time immemorial, most people made their own, but in the late 18th and early 19th centuries they increasingly started buying soap from a local manufacturer. In the mid- to late-19th century, railways, telegraphs, and electricity made it more efficient to produce soap in large central factories and ship it out for sale far and wide. No local maker could compete on price or quality. So whether you lived in Missouri, or Ohio, or Colorado, you bought the same soap from the same factory in Peoria.

Similar processes, spurred by the same technologies, changed how people got information and culture. The local and decentralized shrank. The giant corporation overseeing highly centralized production and distribution — governments, newspaper chains, Hollywood studios, radio and television networks — dominated all.

Critiques of this state of affairs came from the left and the right. In a 1937 review of a new book about mass communications, Columbia University historian Harry Carman summed up the theme from a conservative perspective.

“…the telegraph, the telephone, and wireless (radio) have helped to undermine our old community life and to destroy our local economy. They have, as the author shows, made us increasingly puppets of ‘a great central government, great newspaper chains, great propaganda agencies [ie advertising agencies] which shape minds to wire and air, cramming them into narrow mass-produced molds.”

“Mass” was the key word of the 20th century.

“The masses” were increasingly served by mass production catering to mass consumption. News came from mass media. Pleasure — all that crappy television — came from mass entertainment. All these enormous systems and networks were summed up as “mass communications.”

It was an era of giants, few in number, but vast in scale and reach.

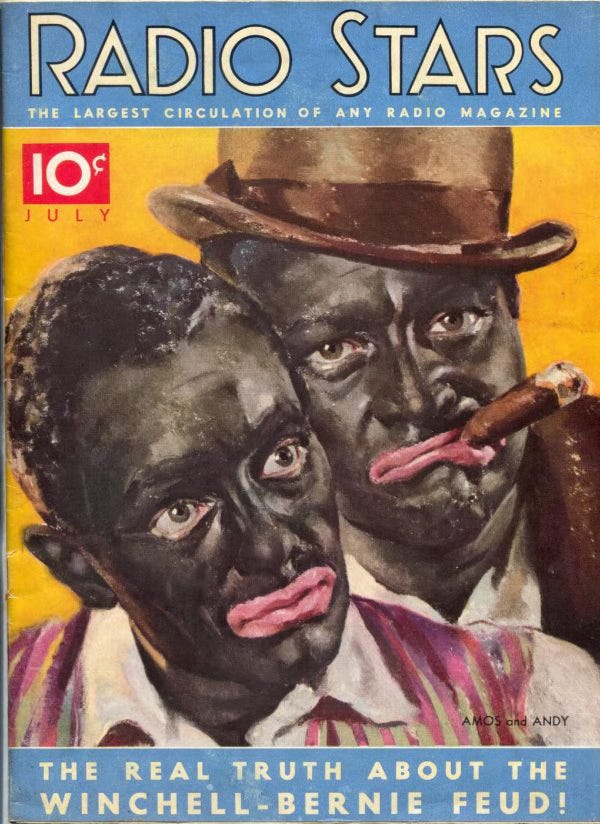

Amos ‘n’ Andy

In the early 1930s, the radio serial Amos ‘n’ Andy, which aired six nights a week, was the most popular show on American airwaves. It drew an estimated audience of 30 to 40 million Americans. Per episode.

Radio broadcasting had only existed since 1921. Before then, the size of an audience for a lecture or a show had been capped at the number of people who could jam into a concert hall. (Larger crowds were possible outdoors but good luck speaking to ten thousand people for an hour.) And note that in the early 1930s, the population of the whole United States was about 124 million. So in less than a decade, Americans left behind a society in which the largest audiences measured in the thousands for one in which almost one-third of the entire country was listening to the same show at the same time. Daily.

For a giant corporation churning out soap in a Peoria factory and shipping it all over the United States, radio and its immense audiences were a godsend. With a single ad buy, they could cajole a large portion of the population of the United States. In their living rooms. Every day.

To generate such massive audiences, however, broadcasters had to deliver content aimed exclusively at the broad middle. Minority views and tastes were kryptonite. Anything even potentially controversial to a significant segment of the population was out. While American radio in the so-called golden age of the 1930s was long remembered with fondness by those who experienced it, there’s no question that if Newton Minow had been born 30 years earlier he would have described it as a vast wasteland. With only a few noble exceptions, it avoided the slightest hint of the intellectually or culturally daring — politics was all but forbidden — while it relentlessly delivered simple-minded crowd-pleasers.

That was not what people expected, or desired, when radio broadcasting began in the early 1920s. In fact, it was pretty much the opposite of it.

When radio began, there were almost universal expectations that it would become an instrument of enlightenment and uplift. Herbert Hoover, first as the Cabinet secretary responsible for the new technology, then as president, repeatedly promised to deliver just that. He was sincere. But Hoover chose to make radio a private, for-profit business, and while he personally denounced advertising and said it should have no place in radio — and everyone agreed at the time, including the corporations that became national broadcasters — he didn’t forbid it. As a result, he created a model that naturally inclined toward advertising. By the 1930s the new industry was so devoted to ads that advertisers effectively controlled everything that went on air. Scripts were even approved by sponsors, line by line. If a show’s sponsor were Lucky Strike cigarettes, the word “camel” — the name of Lucky Strike’s main competitor — was forbidden. The advertiser’s wish was radio’s command.

Those advertisers were giant corporations selling soap to the whole country so they wanted the biggest audiences possible. Lectures, news, and opera wouldn’t deliver that. Mass-appeal entertainments would. That made Amos ‘n’ Andy, and so much else like it, all but inevitable.

Amos ‘n’ Andy may have been the biggest thing on the exciting new technology but it was simply an updated version of an old minstrel show in which white actors played adorable, simple-minded black characters for laughs. It was dumb, racist entertainment, and Americans who had grown up on minstrel shows loved it. Amos ‘n Andy enlightened nobody, but most Americans were happy with that. And there was so much more like Amos ‘n’ Andy.

Strengthening this tilt toward the mass was a technical aspect of the new technology: If more than one broadcaster transmitted on a frequency at the same time, it produced an incomprehensible mess. The right to broadcast had to be exclusive, which ensured that even in big cities only a relative handful of broadcasters could operate. Financial interest pushed broadcasters toward mass appeal. And if that wasn’t enough, government regulators pushed them harder by rewarding programming that appealed broadly, while punishing more narrowly focussed broadcasters. Universities and others that sought to make radio the tool of enlightenment so many dreamed it would become — broadcasting lectures and the like — not only struggled to draw audiences; they were often pushed to the margins of the spectrum, or off it entirely, by regulators.

The next step was the broadcast network. String together a bunch of those mass-appeal radio stations and you have something capable of drawing immense audiences all across the country in a single broadcast. NBC was the first, founded in 1926. CBS followed in 1927.

And with that, the system was complete. Mass production. Mass consumption. Mass media. Mass communications and mass entertainment. All the components supported each other, leading to the centralization of manufacture and thought bemoaned by Harry Carman.

By the time television was ready for prime time — the late 1940s — this system was already deeply entrenched. Television merely strengthened it. And that’s how we got to the “vast wasteland” decried by Newton Minow in 1961.

Needless to say, the wasteland didn’t disappear after Minow denounced it. Even in the 1980s, television was astonishingly vapid.

The A Team was a giant hit of the era. Maybe you distantly remember it. I do. I remember it being dumb. But I looked it up recently and discovered that “dumb” doesn’t even begin to plumb the depths of its idiocy.

As you are reading this newsletter, I can safely assume you are one of the discerning minority. If this were 1982, or 1932, you would turn up your nose at The A Team or Amos ‘n Andy. Instead, you would… You would, what? You could give television and radio a pass. But short of that, you would watch and listen to what the masses watched and listened to. Because that’s all there was.

Many observers despised the mass society, but no matter. We had little choice but to watch what everyone watched, listen to what everyone listened to.

Critics often used the word “homogenization” to describe the sameness of life.

Most people wore the same clothes (polyester), ate the same food (Cheez Whiz), drank the same wine (Cold Duck), heard the same news (Walter Cronkite), and were were made dumber by the entertainment (just try to watch an entire episode of Gilligan’s Island.) The only modest alternatives to the monolith started to emerge in the 1960s, with the news, art, and entertainment of the “counterculture” that mostly eked out a precarious existence in big cities. But if you didn’t have a flop in Haight-Ashbury, and you weren’t a Manhattan hipster, you had no arthouse movies, no Village Voice. Your life was Cheez Whiz, whether you liked it or not.

That was the world I was born into.

Cultures, Subcultures, Sub-subcultures, etc.

That world isn’t entirely gone. Cheez Whiz still exists, for reasons that escape me. But it’s hard to exaggerate how much the world has changed.

The VCR caused the first tremor. (Don’t know what “VCR” stands for, kids? Ask your parents.) Then came cable. Freed to appeal to a narrower audience, HBO delivered The Sopranos and made the earth shake.

But it was the Internet that slammed into the world of dinosaurs.

I read recently about some YouTube star who has a huge following and is making a lot of money producing cheap videos about something or other. I had never heard of this person and can’t remember his name. But I won’t bother looking it up. Because it doesn’t matter. There are thousands of people who match that description.

Add in TikTok, Instagram, and other social media platforms and I’m pretty sure tens of thousands would fit my description of this “star.” Maybe more.

Each of these people is a celebrity you can refer to by name alone in some sub-culture of the Internet. But there are countless sub-cultures of the Internet. And sub-cultures of sub-cultures — with more layers of “sub-” in near-infinite recursion — which makes it not only possible but likely that a person who is a big deal to a million people or more is unknown to the rest of humanity.

With communications technology having digitized and merged with ubiquitous wireless networks, this phenomenon is not limited to the Internet proper.

There’s a British comedian who did a brilliant little sketch on Twitter in which he is having a chat with a friend — it’s him talking to himself — about the TV they’ve been watching.

One man is very enthusiastic about a new show. “Have you seen it?”

“No, never heard of it. But I have bee watching this other fantastic show. You are watching, aren’t you?”

“No, doesn’t ring a bell.”

It goes on like this, back and forth, as they fail to find shared experience and the conversation slowly dies.

We’ve all had conversations like that. (I can’t remember that comedian’s name, incidentally, and couldn’t find the clip even with the aid of Google. Which underscores the point, I think.)

Even within our own homes, the rapid multiplication of information and entertainment sources is eliminating shared experience: Dad is in the den scrolling through Twitter. Mum is in the living room watching old-fashioned network news. Son is in his room playing a video game his parents have never seen with someone in Taiwan. Daughter is in her room watching a video by an Instagram influencer she follows obsessively — an influencer whose name no else in the family has ever heard.

In the 1920s, radio made gathering the family around a vacuum-tubed hearth to listen to the same programs as your friends and neighbours a universal experience. In the 1950s, vacuum tubes were replaced by transistors, and pictures were added, but the tradition continued.

A century after the dawn of broadcasting, that era is as dead and gone as Kirk Douglas — born 1916, died 2020 — whose 103-year-lifetime almost exactly matched that of the era of mass communications.

Microculture Versus Macroculture

Ted Gioia is someone I don’t need to introduce if you spend time in a certain Internet-based subculture. For everyone else, I should note he is a music historian and critic.

Gioia recently published a piece about a coming “war” between what he calls the “macroculture” and the “microculture.” His terms don’t map exactly onto what I’ve been describing, but they’re similar. By “macroculture,” Gioia simply means culture produced by large corporations, which includes old corporations (The New York Times, Hollywood studios) and new (Amazon, Netflix, Spotify.)

As for Gioia’s “microculture,” you’re looking at it. It is the immense swarm of small, independent creators on platforms like YouTube and Substack. Others have dubbed it the “creator economy.”

Gioia is himself a fixture in the microculture and his essay is bullish for his team. The macroculture is struggling, he writes. Those hordes of people joining the ranks of the microculture? An awful lot of them are journalists and others laid off by large corporations in the information and culture sectors. Goia quotes a September statement by payment-processor Stripe: “In 2021, we aggregated data from 50 popular creator platforms on Stripe and found they had onboarded 668,000 creators who’d received $10 billion in payouts. We refreshed that data in 2023 and found something surprising: the creator economy is still growing about as fast as it was in 2021. Today, those same 50 creator platforms have onboarded over 1 million creators and have paid out over $25 billion in earnings.”

With AI promising to swiftly supercharge the powers of the independent creator, Gioia sees the contrary interests of the two cultures sparking “war” soon.

In that conflict, both Gioia’s money and his passion are with the microculture. I understand why. Gioia is eleven years older than I am — he’s Boomer, I’m X — but I very much recognize his cold description of the world he grew up in.

The same monoculture controlled every other creative idiom. Six major studios dominated the film business. And just as Hollywood controlled movies, New York set the rules in publishing. Everything from Broadway musicals to comic books was similarly concentrated and centralized.

…

When I went to work in an office, back then, we had all watched the same thing on TV the night before. We had all seen the same movie the previous weekend. We had all heard the same song on the radio while driving to work.

And that’s why smart people back then paid attention to the counterculture.

The counterculture might be crazy or foolish or even boring. But it was still your only chance to break out of the monolithic macroculture.

Many of the art films I saw at the indie cinema were awful. But I still kept coming back—because I needed the fresh air these oddball movies provided. For the same reason, I read the alt weekly newspapers and kept tabs on alt music.

In fact, whenever I saw the word alt, I paid attention.

That doesn’t mean that I hated the major TV networks, or the large daily newspaper, or 20th Century Fox. But I craved access to creative and investigative work that hadn’t been approved by people in suits working for large organizations.

It’s hard to disagree with any of that. And in that light, the “microculture,” or the “creator economy,” or whatever you want to call it, is a godsend.

No more corporate gatekeepers. No more bland homogenization. No more marginalization of minority views and tastes. Instead, we have millions upon millions of people all over the world empowered by technology to imagine and create. And they can distribute their work to most of the human race at almost zero marginal cost. This was utterly inconceivable not so long ago. Now it’s happening daily.

For a simple, tiny example, look at this newsletter. It’s my hobby, not my job. I put some thoughts down on digital paper now and then. People have always done that, with diaries and letters, but when I finish writing, I won’t tuck my work into a shoebox kept in a closet. Instead, I will hit “send” and my thoughts will be instantly whisked to inboxes in 114 countries, and made available to anyone, anywhere, any time. It’s human nature to get used to wonders and cease to see them as wondrous. But that really is wondrous.

And so many others are doing so much more with the new technology. Check out my favourite podcast, The Rest Is History. Or spend seven amazing minutes marvelling at this description of scale within the Milky Way produced by … some dude I’ve never heard of. Yes, there is a vast amount of garbage being churned out, but no longer live in the three-channel world of the 1960s. Or even the world of 1992, when Bruce Springsteen sang “57 channels and nothing on.” There is effectively an infinite supply of channels, so we can ignore all the vast volume of garbage being churned out and still be left with an embarrassment of riches to choose among.

So, yeah, I get Gioia’s excitement. And that of the billons of others delighting in this global explosion of multiplicity and creativity.

But reality is complex. And when a phenomenon is this big you can be sure it is not unidimensional.

There is always an “on the other hand.”

The Other Hand

When everyone tuned into Walter Cronkite, everyone shared daily news.

That news may have been biased. It may have had blind spots that suited the powers that controlled it. It may have marginalized minority perspectives. But sharing a common pool of information at least made it easier to discuss and debate the issues of the day. Or even just choose which issues to discuss.

Similarly, shared stories are the lingua franca of any functioning society. “Who shot JR?” may have been dumb but it undeniably got Americans talking with each other. I suspect one reason for Hollywood’s endless recycling of the likes of Star Wars and Marvel comics and Indiana Jones is that these are relics from an era when everyone knew the same stories. This mutual awareness makes watching the latest iteration of these old themes a comforting experience — a shared experience — in a time when we share less and less.

And it wasn’t only stories we shared. It was the social norms and values inherent in those stories. This is the raw material of social capital. And social capital is fundamental to the health of a society.

Today, we are, at most, only a decade and a half into the radically different 21st century model. The revolution has barely begun. But already, I think, we are starting to see that despite its many virtues the new paradigm does have costs.

There is no Walter Cronkite today. There can be no Walter Cronkite in a world where the number of news sources has exploded. The newer sources don’t even try to appeal to the broad middle with general interest news and musty claims of professionalism and objectivity. Instead, they cater to market niches, which, for news, means ideological niches. In those markets, the quality of their work is judged not by its willingness to report fairly on different sides of an issue but by its advancement of the ideology that defines the niche. All humans are afflicted with confirmation bias, and the Cronkite-era news was only too human, but it at least tried to rein in confirmation bias. Among the new news sources, confirmation bias is the mission statement. (And not only those sources. This essay by James Bennett, the former editorial pages editor of The New York Times, makes for frightening reading.)

Something similar, if less dramatic, is happening with fiction. According to Variety, the highest-rated television show of the 2022-2023 season was Yellowstone. Airing weekly, its average audience size was 11.6 million. The United States has a population of roughly 331 million people today. That means Yellowstone drew about 3.5% of the American population, which is one-tenth the proportion that listened to Amos ‘n’ Andy in the early 1930s. And Yellowstone, remember, is an outlier. The vast majority of shows are watched by small niches of the population, so shows are written and produced to appeal to those niches, with the social norms and values of those niches in mind. The great mass of middle America is not the audience.

Just as politics has become a battle of microtargeting, so information and culture are increasingly about finding and exploiting niches.

Who even talks about “the masses” any more?

Parallel Factors

And consider that all this change is happening coincident with other dramatic changes that could amplify its effects.

One of the biggest involves immigration and cultural diversity. Both are near record highs in the United States and across much of the Western world. As of 2021, almost 14% of Americans were foreign-born, almost as high as the record set in 1890. In other countries, that percentage is much higher. In Canada, almost one-quarter of the population is foreign-born, the highest rate in my country’s history; a 2022 StatsCan projection found that percentage will rise to between 29% and 34% by 2040.

No, this essay is not turning into an anti-immigration screed. I think immigration has enriched Western countries in countless ways and continues to be essential to our prosperity and dynamism. But successful immigration — immigration that leads to full integration and happy outcomes for foreign- and native-born alike — cannot be taken for granted. The maxim “diversity is our strength,” a favourite cliche of liberal politicians, is only somewhat true. Diversity can be a strength. But as in story of the Tower of Babel, it is not necessarily a strength.

Robert Putnam’s pioneering work on social capital showed that diversity diminished trust, and social capital with it. Putnam is liberal, and a supporter of diversity, so he was dismayed by these findings. The conclusion he drew was that diversity can work but we must acknowledge its deleterious effects and act to mitigate them.

I should note that Putnam’s work has been challenged, but whatever you make of that dispute my point is a simple one, and, I think, not controversial: Successful immigration and integration is not automatic. While immigration has, on the whole, worked quite well in Western societies, particularly in traditional recipients of immigration like the United States and Canada, continued success cannot be assumed. We must get the conditions right.

In this light, the switch from the 20th century model of mass communications to that of the 21st should give us pause. An immigrant who comes to America today won’t watch Walter Cronkite like everybody else. He won’t be entertained by one of the three television channels and learn the social norms and values of the middle America implicit in those few sources. Instead, he will, like everyone else, listen to and watch niche news and niche entertainment that reflects the social norms and values of one or more of the proliferating subcultures.

Will that impede integration? I don’t know. But I think that’s worth considering.

And while we’re at it, let’s consider another important change of the last half century.

Throughout the 20th century, in Western countries, conformity was respected and expected. Being an ordinary person, like all the other ordinary people, was desirable. Standing out, being different was not.

If you had that one grandparent who came from a minority group, particularly a minority racial group, you never mentioned it. It suggested you were different. You didn’t want to be different. You wanted to fit in. This was the same impetus that led immigrants to change their names to something middle America would consider normal. Parents did something similar when they avoided distinctive or unusual names for their children and chose from a list of standards: In the 1950s, the fact that classrooms were stuffed with Jameses and Marys was a point in favour of naming your child James or Mary, not a point against.

But in the last half century — particularly after the absorption of the counterculture into the mass culture in the 1970s and 1980s — popular culture swung hard in favour of being different and standing out. “Be yourself and don’t conform” has been a hackneyed theme in movies and TV shows for at least 40 years. Baby names soar in popularity precisely because they’re unusual; they crater once they become popular, leading to names falling in and out of fashion in quick succession. Some immigrants still change their names to advance their new lives but it is more fashionable to take pride in the distinction an unusual name affords; Kirk Douglas probably would have remained Issur Danielovitch in today’s Hollywood.

And far from quietly ignoring that one grandparent from a minority group, people now latch onto that grandparent’s identity, boast about it, or even proudly proclaim themselves members of a group they have little real cultural affiliation with. Those on the political left who have most fervently embraced identity politics have multiplied this tendency by giving status to individuals from marginalized and victimized groups — the more marginalized and victimized, the greater the status. The zeitgeist is summed up in the “pretendian” phenomenon, which sees white people whose parents and grandparents would have hidden any indigenous ancestry grabbing onto family legends of one indigenous ancestor, or even inventing family histories out of whole cloth, in order to identify themselves as members of a traditionally persecuted minority. That only makes sense in a culture where identifying as a member of the majority is psychologically, socially, and even politically undesirable.

Both academic and popular history reflect this shift. Old national histories — Thomas Jefferson was a hero (don’t mention slavery), expansion was America’s manifest destiny (don’t mention the Indians) — feel as antiquated as glowering portraits of Queen Victoria. In their place is a relentless Howard Zinn-style focus on the crimes omitted from those old national stories combined with a focus on the contributions of women, blacks, and others who ignored in the national stories that dominated through most of the 20th century.

Again, to be clear, I am not a crusty conservative bemoaning all these changes. The conformity of Eisenhower-era America was stultifying in many ways. I think the old chant of gay activists — “we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” — expresses an attitude toward differences of identity that is healthy for majority and minority alike; a society that is comfortable with difference is, all else being equal, a better society. I’m all for letting your freak flag fly. As for the shift in history, I’ve written before that the old national stories were grossly inadequate, and syntheses in which marginalized groups are fully included in new national stories makes for better, richer, more accurate history.

But on the other hand — as I said, there’s always another hand — we must give the Eisenhower era its due. An inclination toward conformity is, almost by definition, likely to strengthen social norms and shared values. And generate social capital. Throw all that out and, again, we have what was a strong source of social capital in rapid decline.

So let’s sum up.

First, we are shifting from an information and culture model driven by a handful of highly centralized producers to one with a huge and rapidly growing number of decentralized producers, meaning people are increasingly not exposed to the same news, the same shows, the same stories, norms, and values.

Second, we have historically high rates of immigration and cultural diversity.

Third, we abandoned a culture that encouraged conformity and shared norms for one that celebrates diversity and difference.

In each case, what existed in the past — whatever its many other flaws and drawbacks — tended to bring people together and help them talk, trust, and co-operate. In each case, what has replaced it — whatever its many other virtues — does the opposite.

Is it only a coincidence that division and mutual incomprehension seem to be on the rise? I fear it’s not.

Centrifugal and Centripetal

In physics, centrifugal and centripetal force are similar but opposite.

If you’ve ever driven a car at high speed around a corner, you’ve experienced centrifugal force. It pushes you away from the centre.

Centripetal force, by contrast, drags an object toward the centre. Gravity is centripetal.

The interplay of centrifugal and centripetal forces explains how satellites, moons, and planets maintain orbits: The centripetal force of gravity tugs inward while the centrifugal force of motion pushes away. Strike the right balance between the two and the object neither spirals inward nor goes flying off into space. It moves in a steady orbit.

I think centrifugal and centripetal forces are a good metaphor for the transformation we are undergoing.

Thanks to new technologies, information and culture strengthened centripetal forces in the late 19th and 20th centuries. They dragged people toward the centre. They urged conformity. Unity. Adherence to the norms of the masses. The power of the centripetal became overwhelming in 1950s America. The result was homogenization.

Today, thanks again to new technologies, the balance of forces is once more shifting rapidly. The centripetal pull toward the centre has ebbed. Centrifugal forces pushing us away from the centre steadily grow stronger.

Political polarization is only one manifestation of what’s happening. We are increasingly divided in countless ways. We see this most vividly in hate and anger, but far more commonly there is simple incomprehension. People whose sources of information and culture are different from ours increasingly seem foreign. They may have been born and raised next door. But if you’re a suburban Biden Democrat who spends a lot of time watching MSNBC and following an array of highly opinionated commentators on Twitter, your neighbour with the “Trump Won” flag can seem as remote and unfathomable as a farmer in New Guinea.

If my analysis is even close to the mark, that sense of alienation — of cultural distance — will grow as the centripetal pull fades and centrifugal forces push us further and further from the centre. The only question is whether the satellites will remain in orbit or be hurled off into space.

Modern liberal democracies are really quite astonishing. The diversity of the 331 million Americans is breathtaking. Yet somehow the United States persists as a single, mostly cooperative, mostly effective entity. It’s not remotely e pluribus unum (nor was it ever.) But somehow that enormous, fractious, complex contraption still hangs together.

For most of my life, that fact wasn’t worth stating. It could be taken for granted.

Today it needs to be said because the unity and existence of the United States no longer feels like a certainty. And it’s not only the United States. It’s also Canada. Australia. The United Kingdom. The broad strokes of the story seem similar in each. I suspect it goes wider still but I’m an Anglophone so I can’t say.

What unites us? What do we hold in common? How do we express this in stories and how do we ensure that those stories are broadly shared?

How do we keep us feeling like us?

It seems to me these are questions that any thoughtful politician should be asking. Barack Obama at least touched on them now and then. But I can’t name any other leader who has.

If that doesn’t change, I fear our future will increasingly resemble that British comedian’s sketch about watching TV in a time when we are all watching different shows.

We will try to talk but fail. And the conversation will slowly die.

Thanks for the puff of "fresh air,“ voicing this trend of a sort of toxic individualism, and for existing as a counter-culture that is highly valuable today. As our social groups are subdivided into a minutiae of interests and preferences, and with a dwindling ability (or interest) to empathize, understand, or connect, we seem to be diluting any substance there once was in our collective culture into a formless, directionless ˋArmy of Ones’. Further than merely fearing to offend thy neighbor by sharing views or interests, I think we’ve now trodden into territory of something worse... fearing to bore our neighbor with anything outside their easily cultivated and fed pallet of individualized interests.

We used to gently self-mock our teenage selves in the 90’s, ‘I’m different... just like everybody else.’ The celebration of our uniqueness has contributed to the collective loneliness.

Lots to think about. Whenever I read something like this I tend to think in what places is this not happening. Sports comes to mind. The big teams and top players are still holding the attention of large percentages of people. It maybe more global with European soccer grabbing more followers outside Europe than ever.

I don’t have data on this and as someone without the sports fan gene I don’t comprehend it well.

It will also be interesting to see if the growing trend in schools banning phones has an effect.