With a leak that suggests the United States Supreme Court is prepared to scrap the half-century old Roe v. Wade decision — abolishing a right of access to abortion, and possibly the right to privacy with it — much that was settled in the American legal and political landscape is now shaking in the equivalent of a magnitude nine earthquake. I’ll leave it to wiser minds to forecast the consequences of the upheaval but I will offer a modest and safe prediction: We will soon hear a lot about the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937.

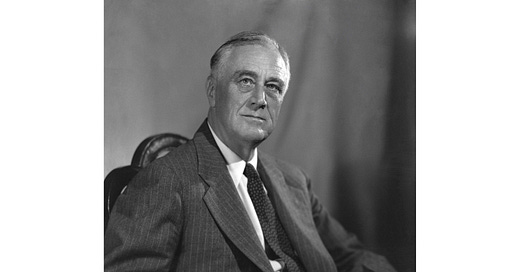

Never heard of it? You probably have, but not by that name. The journalist Edward Rumely dubbed it the “court-packing plan.” That name stuck — one reason why the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill failed to pass, the biggest defeat suffered by President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s.

Taking office in 1933, in the darkest depths of the Great Depression, Roosevelt promised a “New Deal” and that is the label attached then and now to the wide array of policies Roosevelt ultimately enacted. But calling it that makes it sound like Roosevelt knew what had to be done and he did it. That’s misleading. Roosevelt quite sensibly recognized that — contrary to what very many confident voices insisted — no one actually knew the solutions to what was, after all, an unprecedented crisis. Worse, the cartoonish portrayal of the outgoing Hoover administration as having done nothing was wrong. Hoover had done all that the conventional thinking of the day suggested he should do. It just hadn’t worked.

So Roosevelt launched what he termed “bold, persistent experimentation”: His administration tried this. It tried that. It tried a dozen more policies. It monitored the outcomes of these many experiments and adjusted as results became known. This approach didn’t satisfy the rational planners who wanted things mapped out, codified, and tidy. And it appalled the many people who were sure they knew exactly what the solutions were if only the fools in Washington would listen. But America’s descent stopped. And improvements followed. They were painfully slow. But they were real.

There was one major impediment, however. The “bold” part of Roosevelt’s experiments involved the federal government doing things it had never done before, and that ran into a traditional conception of the US constitution in which the federal government’s role is narrow and tightly circumscribed. For a certain type of American — particularly white Southerners — the idea of a federal government boldly and persistently trying new policy approaches was dangerous stuff. Some of those Americans sat on the Supreme Court: Several pieces of New Deal legislation were declared unconstitutional by the judges.

After winning a thunderous re-election in 1936, Roosevelt moved against the Court. While the Constitution establishes that there will be a Supreme Court, it does not specify the number of judges on the court, so Roosevelt drafted legislation that allowed the president to make an additional appointment for every sitting justice older than 70, up to a maximum of six. The existing court had nine judges, who were divided on the constitutionality of New Deal legislation. Adding even a few vetted appointees would ensure Roosevelt’s legislation would be upheld.

Despite the president’s popularity and enormous political capital, this was overreach. FDR needed Democrats in Congress to push the bill but in this era the South was still a Democratic stronghold, so many of the worries about federal tyranny were strongest within Democratic ranks. In the end, it was the Democratic senator who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee, Henry Ashurst, who declared, “No haste, no hurry, no waste, no worry – that is the motto of this committee” and delayed the bill for half a year. Then released a report condemning it.

In the end, it didn’t matter. One conservative Supreme Court Justice switched sides and the majority swung in favour of the New Deal. The “court-packing plan” was scrapped. At the time, the court was widely seen as having given into Roosevelt’s political pressure, leading to the famous line, “a switch in time saves nine.” Some historians now dispute that portrayal, as there is evidence the justice had switched his views before Roosevelt introduced his plan.

So what’s this got to do with the news that broke last night? The end of Roe v. Wade will have massive repercussions. If the right to privacy goes with it — Roe v. Wade is built on that right — it will also have massive repercussions. This is by far the biggest bombshell the conservatives on the court could drop. If they’re willing to unsettle half a century of settled law, what else will they do?

Democrats had already been whispering about expanding the court with new appointees — their appointees. Now? The pressure will be huge. And FDR’s “court-packing plan” will suddenly be highly topical.

There will be lots of grist for commentators, no matter what position they take. Roosevelt was massively popular, had just won re-election in a landslide, and had firm control of Congress when he tried to pack the court. And yet he failed. Worse, the attempt damaged his standing, both within the Democratic Party and in the public at large, giving apparent credence to claims he was a tyrant in the making. Biden has none of Roosevelt’s strengths.

But it’s possible that a plan to expand the court will rally and energize the otherwise divided and dispirited Democrats. The South is now a Republican bloc, after all. Going into the November mid-terms, the Democrats could push to restore Roe v. Wade and the right to privacy, and protect whatever else the conservatives judges are going to take away with a plan to expand the Court. The extraordinary means by which the conservatives willing to radically remake the law became a majority — a Republican President who lost the popular vote pushed through three appointees, two using quite shocking and shameless abuses of process — will fuel any such drive.

But as I said, there’s only one prediction I am confident in making here: expect to hear a lot about Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 in the near future.

Thank you, Dan. To me, the biggest lesson from the last few years, punctuated by yesterday’s news, is how vital it is to never stop reinforcing the institutions and conventions we rely upon and never fail to influence each succeeding generation on why complacency about past gains fosters unpalatable present and future risks. Of course, the trick is to say all that in new and refreshing language that is hard to dismiss in an era when history lessons are too often seen as the preserve of ‘non-modern-minded’ people. I am struck by all the Twitter reminders in recent weeks that Hillary was right about everything! What she and FDR both seem to have discovered - at their and society’s cost - is how much even the most rational or urgent policies must be sold in a competitive market for ideas where the majority can be convinced to vote against their own self-interest. Justice is a week instrument if it is not sponsored by those with a mix of learning, competence and conviction.

Great article. Thank you.