What Would You Have Done?

A thought experiment to dispel the arrogance of the present

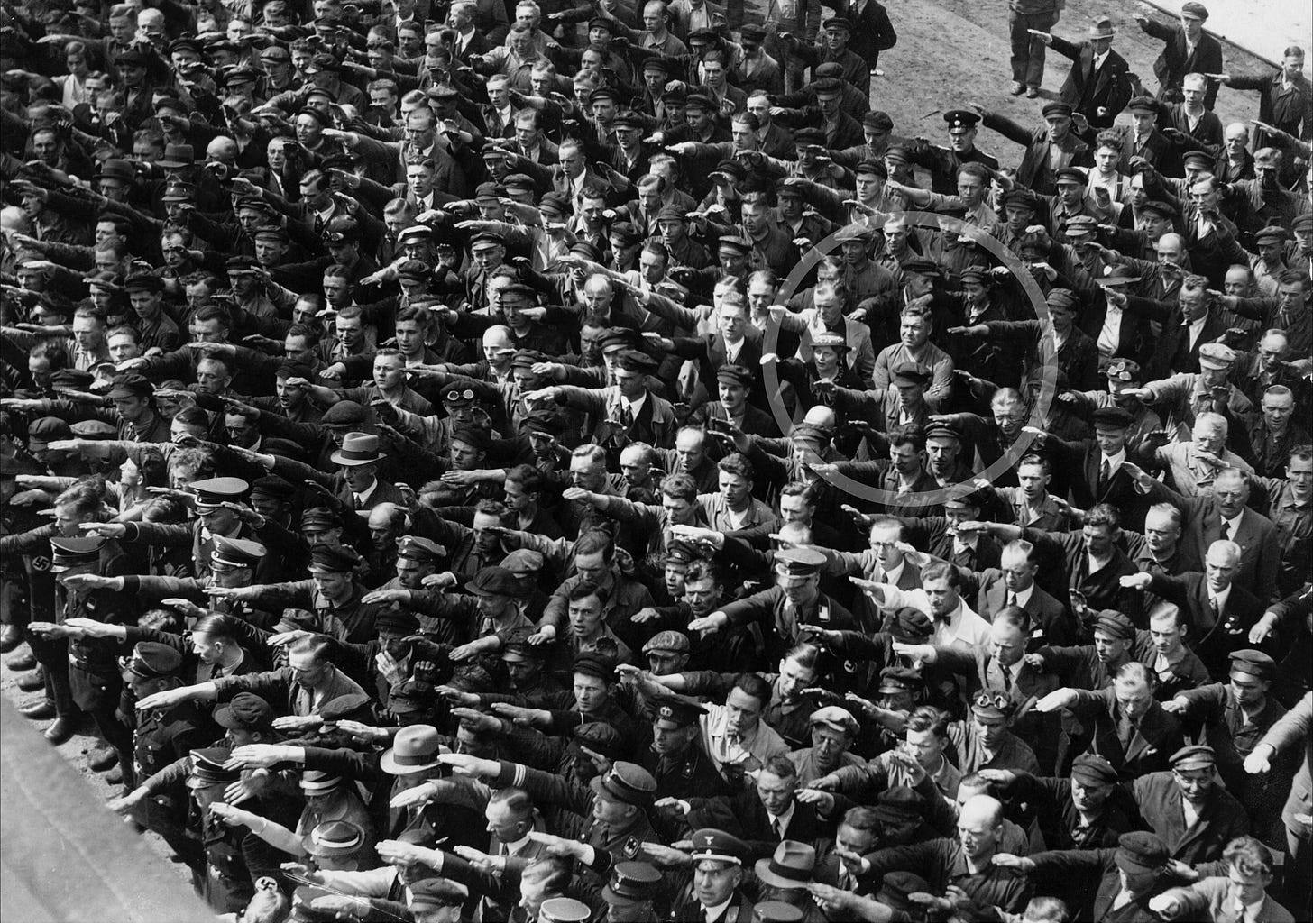

A famous black-and-white photograph depicts a crowd in which all have arms raised in a Nazi salute. All but one. A lone man stands with his arms pointedly crossed.

This photograph was taken in Hamburg, Germany, in 1936. The people are workers at a Blohm & Voss shipyard. It’s not certain who that lonely dissenter was. One family claimed he was Gustav Wegert, who refused to salute on religious grounds. But it is more widely believed that he was August Landmesser, who had joined the Nazi party in 1931 in hopes of getting work but had been expelled in 1935 when he was engaged to a Jewish woman, in contravention of Nazi law. The woman was eventually caught up in the Holocaust and murdered. Landmesser was ordered into a military penal unit and killed in action.

But let’s set that aside and try a thought experiment.

It is 1936. You are one of the Blohm & Voss workers. Standing in the crowd, everyone raises an arm in the Nazi salute. Do you also salute? Or do you cross your arms?

Perhaps, in trying to answer this question, you would think of the power of social conformity and how it would push you toward saluting. You may also fear reprisals for refusing.

On the other hand, you know you: Naziism is repugnant to everything you believe. Surely you could find the courage to make a small gesture of defiance.

If you are thoughtful, you would balance these considerations and likely come up with a middling probability. Fifty-fifty. Maybe you would salute. Maybe you wouldn’t. You can’t be sure.

Seems like a smart, reasonable analysis, right?

Now, let’s replicate this thought experiment in some other scenarios.

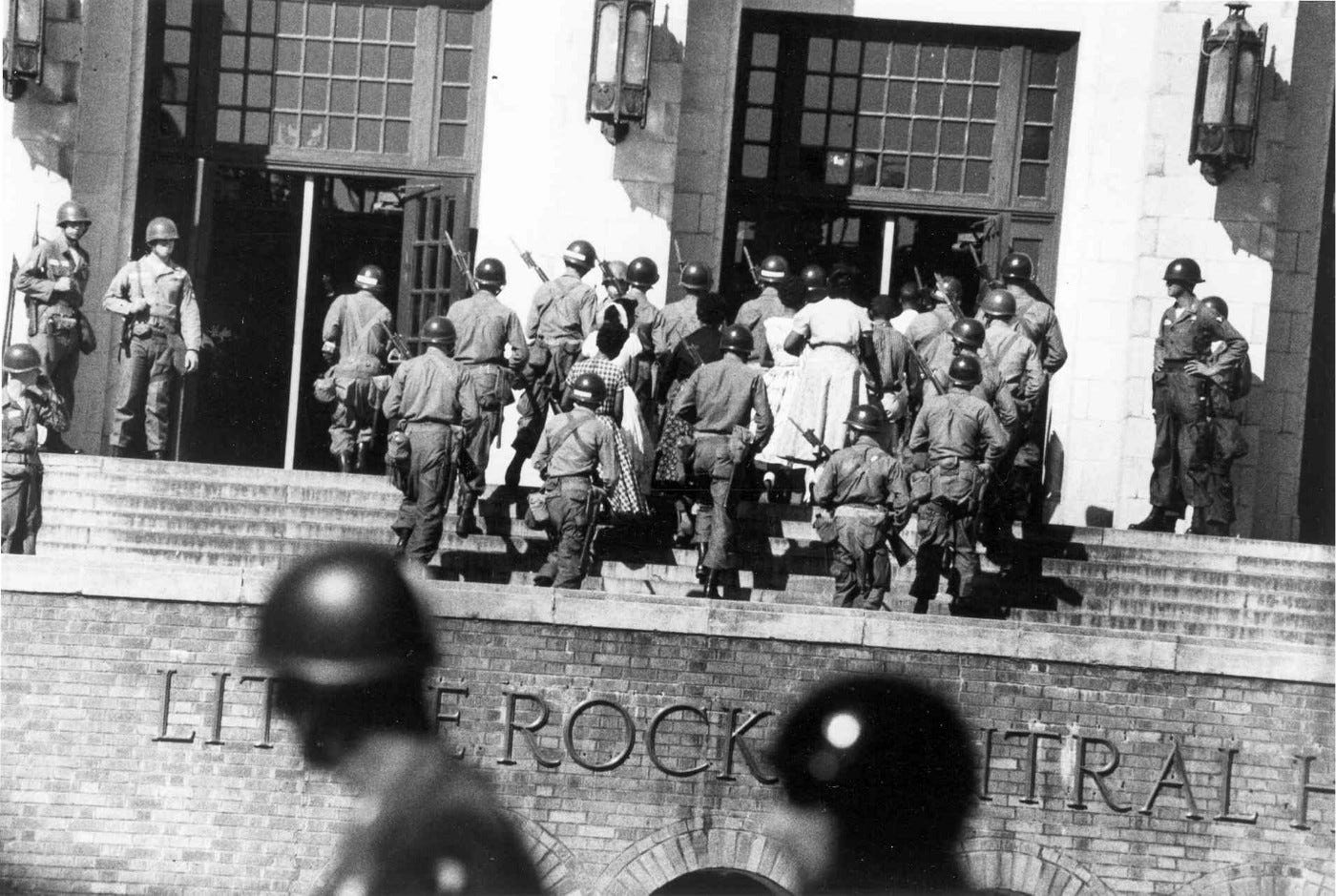

Imagine it is 1957 and you are a white woman on the sidewalk in the Jim Crow South. A 15-year-old black girl walks to an all-white school that has been ordered to admit her: Do you join the angry mob? Do you shrug and walk away? Or do you step up and loudly applaud?

Imagine it is 1919, in Virginia, and a black man is being lynched by a white mob. You are a white man. Do you try to save the man? Do you run to the police and demand they intervene? Do you walk away in sorrow and disgust, determined to speak out in future? Or do you merely shrug and walk away? Or perhaps join the mob and laugh and cheer as the man is tortured to death?

Imagine it is 1852 in Charleston, South Carolina, and you are a white businessman. Are you a staunch and loud abolitionist? Do you quietly oppose slavery? Or do you, like most of your peers, think slavery is defensible and abolitionists are dangerous extremists?

Now let’s try one that’s not so far in the past.

Imagine it is February, 2022. Russia has invaded Ukraine and you are an ordinary Russian living in Moscow. Do you angrily and publicly protest the war? Do you shrug and ignore the whole thing? Or do you, like most Russians, support the government to one degree or another?

We could run this thought experiment countless times and places but the core idea is always the same: When the great majority of people sided with something we find appalling today, or at least didn’t oppose it, would you have done the same? Or would you have been one of the rare dissenters, even when there were social, legal, or economic costs to doing so?

I find this thought experiment worth a little consideration for several reasons. But what I most like about it is that it forces us to ask a fundamental question: What makes me me?

Notice that the question asks “imagine you are …” The very first thing you must do is decide who exactly “you” is. The obvious “you” is who you are right here, right now. Let’s call that person You2022.

When I ask you to imagine yourself as a worker in that Hamburg shipyard in 1936, you could imagine You2022 dropped in that shipyard and then judge what You2022 would do. That’s what I spelled out above because I suspect that is what most people would do in this thought experiment. Because we commonly judge the past by present moral standards. But also because it squares with an idea about the self that is extremely popular in modern, Western culture.

In this view, each of us has a fixed, permanent, true self. It’s the “authentic person” that I am. We may not know what that true or authentic self is because it can be hidden beneath the layers of artifice we adopt in response to the expectations others have of who we should be. But we can find it if we engage in “self-discovery.” And when we do find this authentic self — this view says — it is imperative that we be true to it. Only then can we be happy. (This way of seeing the self is so common in our culture – pick a movie at random and there’s a good chance the moral of the story will be “stop pretending to be what you are not and be true to yourself” -- that talking about it can feel like a fish talking about water.)

This idea has an important consequence for my little thought experiment. If you believe that each of us has a fixed, permanent, “true self,” and I ask you to imagine that you are a worker in that shipyard in 1936, it makes perfect sense to imagine You2022 in 1936.

You2022 is your “true self.” It doesn’t change. No matter where you go. No matter what the circumstances. No matter what the year. You are you. Therefore, if you were in 1936, you would think and do what You2022 would think and do. Obviously! It’s settled then. Right?

But there’s a wee problem: The idea that there is a fixed, permanent, “true self” is as wrong as it is popular.

I recognize that I am making a huge claim about a huge subject but I am not about to write 10,000 words on the nature of self. Neither you nor I have time. Suffice it to say that the idea of a single, unchanging, authentic self isn’t supported by psychology or neuroscience or philosophy or sociology or … any serious field of investigation that I know of.

If we have learned anything over the last century, it is that what we perceive to be the self is fabulously complex and constantly evolving. (Emphasis on “perceive.” Whether there even Is such a thing as a singular “self” is debatable. That we perceive there to be a singular self is the only thing we can be confident of.)

Who we are – who we perceive ourselves to be, what we believe, what we value, what we judge right and wrong – is shaped by experience. As the world around us changes, we have new experiences. And we change.

You2032 will be different from You2022. And You2042 will be different from You2032.

Just as You2022 is different from You2012 and You2002.

Perhaps you disagree.

“Yes”, you may say, “I changed a great deal in the past. I’m a different person than I was. But that’s only because I peeled away those layers of artifice. Who I am today is much closer to my true, authentic self. So I won’t change much, if at all, in future.”

Psychologists have a term for exactly that perception. It’s called the “end-of-history illusion.”

People tend to perceive themselves as having changed considerably in the past – which is correct -- but when they look into the future, they think they won’t change much. As researchers have shown, that expectation is provably false. We routinely underestimate how much we will change in future.

This presents us with a radically different way of seeing the self.

People have no fixed, “true,” or “authentic” self. We are shaped by experience. Family and community. Education and economic circumstance. The vast array of events -- from the trivial to the momentous – that we encounter through a year, a decade, a lifetime. More experience, more change. It never stops. And more importantly for present purposes: different experiences produce different changes.

If you think of the self this way, and I say, “imagine you are a worker in that shipyard in 1936,” you will engage in a very different thought process.

You will think something like this: “OK, if I am a worker in that shipyard in 1936, I was probably born in Germany, maybe around the beginning of the 20th century. I was probably educated in hyperpatriotic schools that taught me Germany was being denied its rightful ‘place in the sun.’ I saw young men march off to the First World War and never return. I cried when Germany was defeated and everything seemed bleak. I heard politicians say Germany was stabbed in the back. I remember the disaster of hyperinflation in 1923 and the turmoil of the Weimar years. I remember the despair when the Depression slammed into Germany and unemployment exploded. But now Hitler is in power and there are big public works programs. And I have a job.”

And so on. What I’ve described are the generic thoughts of a generic worker in that time and place, but you get the idea.

Is this person different than You2022? Of course! He is radically different! Everything he has experienced in life is very far removed from the experiences that shaped You2022. It would be astonishing if he were not a radically different person.

So with this idea in mind, how can we grapple with the question of what “you” would do in 1936 or any of those other scenarios?

The psychologist Daniel Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky coined the terms “inside view” and “outside view” to describe two different ways of seeing a situation. The “inside view” is a particular instance of something. The “outside view” is the general category which that particular instance is part of.

It is natural and automatic for us to think of the inside view when examining a problem and making a judgement. It is not remotely natural and automatic to consider the outside view. In fact, people tend not to think about the outside view at all unless their analysis is very careful and self-aware.

Here, we don’t have the inside view because we don’t know the particulars of the “you” that is a worker in that shipyard in 1936. We don’t know what school “you” went to as a child, what particular events happened to you and your family during the First World War, and all the other details that shape who “you” are in 1936.

How do we overcome that? It’s tempting to use You2022 as the inside view. But as we’ve now agreed, that’s a serious mistake.

So if we have no real inside view, what’s left? The outside view.

Even though we tend not to think of it, the outside view is often quite easy to use. When we have good numbers, we can even use it to calculate fairly precise probabilities.

Consider that shipyard in 1936.

To keep things simple, assume there are two hundred workers and they’re all in the photo. That means one hundred ninety-nine are giving the Nazi salute. One is not.

A statistician would say the “base rate” for workers saluting is 99.5%. So, absent other information, the probability that any one worker will salute is 99.5%.

What is the probability of any given worker refusing to salute? 0.5%.

Conclusion: If you were a worker in that shipyard in 1936, it is almost certain that you would have given the Nazi salute.

A similar conclusion applies to all those other scenarios. I know this is uncomfortable, so I’ll stop talking about “you” now. Because this applies to me, too.

If I were a white woman on the sidewalk in the Jim Crow South in 1957, it is highly likely I would have jeered, or shrugged and walked away. It is extremely unlikely that I would have loudly applauded the brave black girl going to school.

If I were a white man witnessing a lynching in Virginia in 1919, it is highly probable I would have done nothing at all. Or I would have joined the mob.

If I were a white businessman in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1852, it is highly unlikely I would have been an aggressive abolitionist, or quietly sympathetic to abolition, or even had private qualms about slavery. I wish I could say otherwise. But I cannot.

And in the recent past: If I had been an ordinary Russian in February, 2022, I probably would have supported the government’s invasion of Ukraine, to some degree, or ignored the whole thing. It is very unlikely I would have protested. Some brave people did protest, to be sure. But there were, and are, few Alexei Navalnys.

These conclusions are not a judgement on my character. They say nothing about who I am here and now. They don’t make me a bad person. They are merely an application of basic human nature, empirical observation, logic, and simple math.

I wish I could escape this line of thinking. I would love to believe that I am cut from the safe cloth as Alexei Navalny, Rosa Parks, William Wilberforce, Sophie Scholl and the White Rose movement, and the brave people who conducted the Oberlin-Wellington rescue. It would be wonderful to think I am that sort of rare person who sees the moral outrage for what it is and has the courage to act, no matter what the cost. I’d love to believe I would always be the lone man standing up to the mob.

But that would be self-flattering nonsense.

If I had been shaped by similar experiences to those of most people in a time and place, I probably would have said or done what most people said or did in that time and place. So would you. So would anyone.

Why does all this matter? As I said, I think it helps us clarify human identity and what makes you you.

But it also matters because it speaks to how history should be studied. If what people said and did in the past was shaped by who they were – what they valued, etc. – and who they were was shaped by the people around them and their experiences, understanding the full, rich, complex context in which people lived should be the focus of study.

Why did Dwight Eisenhower order the 101st Airborne to enforce school integration in Arkansas? To ascribe it to Eisenhower’s character is as facile as saying he did it “because he was a good guy.” Conversely, if we want to understand why Woodrow Wilson imposed segregation on the federal government after becoming president, calling him wicked won’t do. We must do the hard work of understanding the full social, political, and personal contexts that led to the decision. That’s what real historical study consists of.

But notice how this is completely at odds with how history is so often discussed in public — which routinely involves people in 2022 morally judging people in the past while making little or no effort to understand the context in which that person lived or offering the slightest recognition that perhaps we, too, would not have behaved in 2022-approved ways if we had lived in that time and place.

With extreme cases, this ahistorical approach doesn’t particularly matter. Understanding Hitler’s context isn’t going to change the awfulness of what he did. But in less egregious cases, this way of thinking can lead to absurdities – like activists denouncing, among many others, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, and Gandhi. Yes, seriously. In each case, activists found something that person said or did that does, indeed, look bad today. In each case, they issued righteous denunciations. And in each case, they utterly ignored historical context. (This Isaac Chotiner interview with the head of the San Francisco School Board is a gob-smacking illustration.)

The thought process is obvious: “That’s bad! I wouldn’t have done that! Outrageous!” The activist sincerely believes that he or she would have refused to give the Nazi salute in 1936 because, well, that’s just the sort of moral, humane, courageous person he or she is.

Delightfully, this process allows the activist to feel the warm glow of self-righteousness without actually risking anything. More delightfully, the activist gets to communicate his or her righteousness to peers and the public at large. Self-righteousness feels good; displaying self-righteousness feels better.

(To be clear, I am not suggesting that all history-related activism is driven by this process. Much. But not all. Here is something I wrote about controversial statues a while back.)

People often say, “it’s wrong to judge the past by the standards of the present.” I agree. But they seldom say why it’s wrong. So let’s be explicit about this: It is wrong to judge the past by the standards of today because doing so is profoundly arrogant.

It is wrong because it assumes that if you or I had been in that time and place, and had experiences similar to those of others, you or I would not have thought, said, and done what the most people in that time and place thought, said, and did. No, we would have done what most people here and now feel is right — even if only vanishingly few people in that time and place did that then.

We all would have been one guy who refused to salute.

This is delusion and self-flattery. We have no reason to see ourselves as superior to most other people. But that’s what we do when we judge the past by the standards of the present.

The better approach to history – and to life – is one of humility and the hard work of understanding.

Excellent article. We can all benefit from more humility. Decades from now, people will no doubt look back at something considered acceptable or even righteous today, and they'll shake their heads and say, "They actually did *that*? What were they thinking???" It's so much easier to pass judgment on other people than ourselves.

You make good points and i know you have used examples that most of us can relate to. I think there is one more important consideration. Rosa Parks *trained* in non-violence. The group had not decided exactly when they would indicate their opposition to segregation. Parks is on record as saying, that day she felt tired and did not want to walk to the back of the bus.

Colin Kapernak talked to trusted people about taking a knee before he ever took a knee.

Or conside the Birkenhead drill. it was practised so when the time comes one remembered "women and children first".

If we do something more than just feel our ideals, if we consult and train for the time when we need to live up to our ideals, we have a better chance of being able to do the right thing when the time comes.