If you’ve ever seen a very old Western — like one of the Tom Mix movies from the 1920s — you know how cartoonish they are. The Good Guy is upright, strong, and clever. He smiles warmly, tells the truth, and always does the right thing. The Bad Guy sneers and snarls, lies, cheats, and steals. And in the end, the Good Guy always triumphs over the Bad Guy, while the piano player pounds out a rousing crescendo.

The hats made things absurdly clear. The Bad Guy’s is usually black. The Good Guy’s is white. As Tom Mix was the biggest of the Good Guys, he typically wore an enormous white hat.

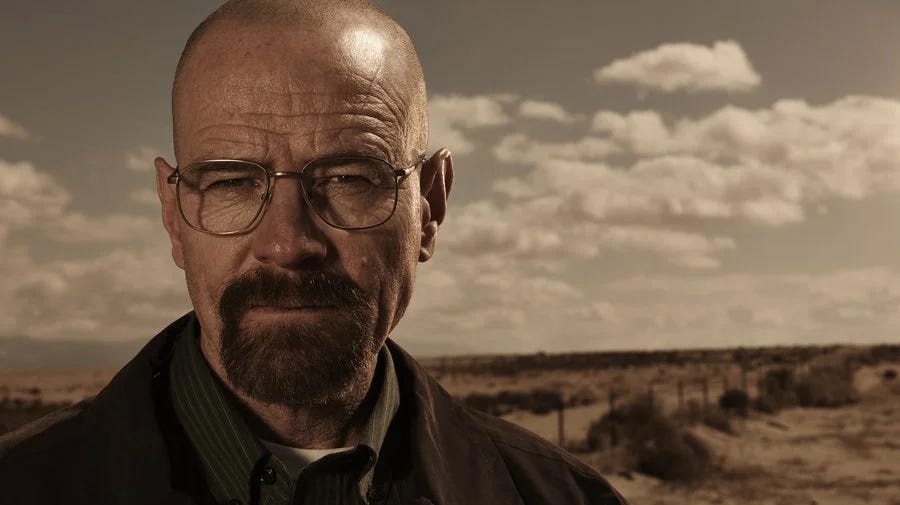

The contrast with the direction modern visual storytelling has taken, particularly with the rise of HBO, then streaming, is total. Consider Breaking Bad, which I think is one of the best dramas ever written.

Is the protagonist of Breaking Bad — Walter White, aka “Heisenberg” — good or bad?

Try to answer that and the first thing you must do is ask a question: “When?” Walt evolves over the course of the show. He is a radically different person by the end.

But even if you narrow the discussion to a single episode, you encounter complexity that defies labels. In one situation, Walt may be thoughtful, generous, even self-sacrificing. In another, he may be conniving and vicious. In a third, he is an uncertain mix of qualities.

This complexity goes beyond moral character. Is Walt intelligent? Does he have good judgement? Again, the question is impossible to answer simply. At first, Walt is a high school teacher comically clueless in the criminal world he has entered, but he learns and slowly discovers he has a talent for the business. “I’m good at it,” he exults to his wife, who is stunned to see the creature wriggling from the cocoon.

But even after Walt becomes a criminal mastermind, he has blindspots, and is occasionally foolish. When a gangster takes Walt and his brother-in-law, Hank, a DEA agent, into the desert, to shoot the agent, Walt pleads with the gangster. He offers all his money — $80 million — to let Hank live. Hank is disgusted. “You’re the smartest guy I ever met,” Hank growls to Walt, “and you’re too stupid to see he made up his mind ten minutes ago.” Bang.

There are many ways to judge art but a central one is how close the art comes to expressing something true about people. By that standard, these new stories are vastly better than anything that preceded them. That’s not a matter of taste. It is an objective fact.

People are complex. They do change over time. They do change from situation to situation. Smart people who often make excellent decisions may do something foolish, or lose their acumen altogether. People who are mostly honest and decent may lie, cheat, and steal. People who are frequently selfish and cruel may be generous and kind.

To explain how he became interested in psychology, Daniel Kahneman, who is a Jew, tells a story about being a boy in occupied Paris during the Second World War.

Well, I was a seven-year-old boy, and there was a curfew for Jews, and indeed, I had my sweater with the Star of David on it. I stayed too long with a friend, and I was past the curfew time. So I put my sweater upside down, and I walked home. And very close to home, I still remember the place, it's a suburb of Paris, I saw a German soldier walking towards me, and he was wearing the black uniform, and black uniforms meant a lot. I mean, those were the SS, they were the worst of the worst. So I knew that one should be afraid of them.

Then he beckoned me, he called me, and I went up to him, and he picked me up, and I remember very vividly being terrified that he would see inside my sweater, that I was wearing the Star of David. Then he hugged me, and he put me down, and he took out his wallet, and he showed me a picture of a little boy, and he gave me some money.

So that was a father, and I reminded him of his son. And I remember sort of the astonishment, the complexity of it. I was a seven-year-old boy, but that was telling you that life was very complicated, if killers could behave like that.

That’s an extreme example, but if we observe people closely over time — including ourselves — we know this, in much less vivid form, from personal experience.

And there’s plenty of science to support it. Personality changes over time are well documented. So is the immense influence situation has on judgement: A person who is cautious and analytical in one environment may be dangerously impulsive in another. Ask someone suffering the effects of insomnia on a rainy morning to donate to charity and she may respond with a cranky “get lost” — but ask the same person after a good night’s sleep, in the morning sun, and she may smile and give.

In serious biographies of historical figures, complexity and contradiction are so routine it is almost cliche to write “shockingly, the person who normally was this way, did this wildly contrary thing.” Indeed, one could argue that contradiction is the hallmark of the serious biography. There are countless books about Winston Churchill that stitch together all we find admirable in Churchill to portray him as the historical equivalent of Tom Mix in his giant white hat; there is a smaller but growing number of books that stitches together what appals us to portray Churchill as a sneering villain: The serious biographies are those that weave it all together.

I could pile up examples. Thomas Edison was a visionary inventor who helped create the modern world; he was also the pig-headed man who insisted electricity should be DC, not AC, and attempted to ruin AC by assisting a campaign that used it to publicly electrocute animals and, after the development of the electric chair, people. Henry Ford was the genius who perfected the early automobile, made Ford a colossus, and all but invented the methods of mass production which are as integral to the modern world as Edison’s lightbulb; he was also the narrow-minded boss who later led Ford into decline, and was a lifelong crank, conspiracist, and bigot.

I honestly can’t think of any major historical figure who isn’t at least somewhat tinged with contradiction, not even those the modern world considers saints. Gandhi? Said horrible things about blacks. Frederick Douglass? Wrote eye-widening statements about native Americans.

The same is true for the opposite end of the moral spectrum, too. Pablo Escobar gave generously to the poor. Yes, that Pablo Escobar.

And remember the story about the young Daniel Kahneman on the streets of Paris? He was there because his father, who was a leading chemist at L’Oreal, had been released from a camp and returned to Paris thanks to the personal intervention of the founder of L’Oreal, Eugène Schueller. Apparently, Schueller liked Kahneman’s father. He even ensured that Kahneman’s family got food throughout the war. Does this make Schueller a sort of French Oscar Schindler? Not quite: Prior to the war, Schueller was the leading funder of France’s anti-Semitic fascist movement.

All this holds not only for people but the organizations made of people: The British Empire was the largest perpetrator and beneficiary of the Atlantic slave trade; later, the British Empire was the greatest enemy of the Atlantic slave trade.

Few of us will ever have biographers who collect evidence and carefully summarize all we ever thought and did, but it’s a safe bet that any of us, put under that microscope, would be as big a bundle of complexity as any great name of history. The only real difference would be the importance of our thoughts and actions.

We are all entitled to say, as Walt Whitman wrote:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Now I don’t think I’ve rocked anyone’s world with what I’ve written so far. If you are a reasonably intelligent, even modestly thoughtful person — the fact that you’re reading PastPresentFuture demonstrates you easily clear that bar — you know people are complicated and almost everyone’s hat is a constantly changing shade of grey.

But now let’s take that basic insight and think about contemporary public discourse. And more specifically, Twitter.

It’s all white hats and black hats. An occasional grey hat, to be sure. But how public figures are seen and portrayed is overwhelmingly as crude and cartoonish as any Tom Mix movie.

There is no better illustration than Elon Musk.

If Thomas Edison and Henry Ford and every other major figure of the past was complex, it is quite literally just a matter of time before Elon Musk joins their ranks. And when he does, he may be the best illustration of the lot. I recently joked with someone that I want to long outlive Musk so I can read the definitive historical biography of the man: genius and folly, triumph and dud, the admirable and good cheek-by-jowl with the head-shakingly embarrassing and shameful. That very long book will be stuffed with complexity.

But is that how people talk about Elon Musk? More specifically, is that how people who revel in the complexity of modern storytelling, and who agree that it is almost axiomatic that people are complex and contradictory, perceive and talk about Elon Musk?

Not remotely. For most, the only question is whether the hat is white or black. After deciding that, everything else falls into place.

If his hat is white, he is a genius, an innovator, a visionary looking out for humanity’s future. And any accusation unworthy of Tom Mix — from hype to harassment to braying nonsense and political foolishness — must be false.

If his hat is black, it all works in reverse. Not only are the accusations clearly true, no further investigation needed, Musk’s motives are always shady and his accomplishments either selfish or illusory.

Doubt that? This week, Mike Carr, formerly an energy official in the Obama administration, was so annoyed with people who dismissed the role played by Musk and Tesla in the electric vehicle revolution that he wrote a series of tweets to set the record straight. But why would that be necessary? Musk may be buying Twitter, and his increasingly frequent, strident, and political tweets — not to mention the new allegation of sexual harassment — may be polarizing public opinion about him more than ever, but one thing logically has nothing to do with the others.

Or rather that would be true if people were thinking of Musk as a complex human being.

But they’re not. They’re putting a white or black hat on the man. If it is black, he’s the villain. The EV revolution is good. Good guys do good things, not villains. It follows — logically, as it were — that his role in the EV revolution must be overblown. It must be.

This is why, on Twitter, it is now routine to see people not only attack Musk for his tweets and political views, they dismiss his past accomplishments. He was “born on third and thinks he hit a triple.” He isn’t all that smart. He isn’t really an accomplished engineer or scientist or inventor or entrepreneur. He didn’t found Tesla and doesn't deserve any credit for what it’s done or the EV revolution it led.

Musk is only the most obvious and contemporary illustration. Say anything positive about Winston Churchill on Twitter and you can set a timer for the responses condemning this bigoted statement or that imperialist policy — the operative presumption being that Winston Churchill could not possibly have thought, said, and done some things that we, today, may find admirable and others that we judge appalling. Black hat or white? Pick one.

I once praised the statesmanship of Dwight Eisenhower on Twitter and someone immediately disagreed. Proof? Eisenhower authorized a coup in Iran that violated Iranian democracy and sovereignty and had terrible consequences we experience to this day. To which I responded: “Yes. And?” Again, the presumption of the person responding to me was that Eisenhower could not have accomplished great things and made some terrible, foolish decisions. His hat must be black or white. There is no grey. [DG PS: In the comments below, Morrey Ewing reminded me of a story about Margaret Thatcher and Mozart. She simply refused to believe a sublime genius could also be a foul-mouthed lover of potty humour. Why? She had put a white hat on Mozart and saw complexity as an attack on that judgement.]

The funny thing is that as much as we snicker when we look at old dramas like those Tom Mix movies, they are shaped by some powerful human forces. It’s natural for us to morally judge. It is natural to slap simple emotional labels on everything from objects to people. It’s natural for us to think this is a “just world,” in which the good flourish — eventually, on balance —while the bad suffer their just desserts.

Most stories, in most cultures, in most times, are much more like those Tom Mix movies than they are like Breaking Bad. In that sense, the shift to complex dramas like Breaking Bad represents genuine progress toward a more thoughtful, more realistic understanding of human reality.

If only we could make the same shift in our discourse about public figures, we’d be getting somewhere.

This perspective was most strongly punctuated for me by the film Amadeus in which the brilliant creator of sublime music was portrayed, at the same time, as an utterly immature and unlikeable character with few redeeming personal qualities.

Yes. I teach Biology - and write about it - and Life's complexity is such a clear theme. And, we are living organisms, so of course we are complex beings.

I do wish to throw in one little observation. We also tend to place white hats on ourselves, then we go to great lengths to hide (or literally burn) away any evidence of our other side.

We all do it. From individuals to tribes and empires.

Maybe, the day we can be honest about our own complexity is when we can face the complexity of others.