When I was a kid, I developed a rule that I would eat the least appetizing portions of a meal first, leaving the best for the end, where they would linger in memory. Forty years later, I discovered Daniel Kahneman’s “peak-end” research and I congratulated my juvenile self for mastering applied psychology.

As this post is a bit of a jumble, I’ll follow the same rule — start with the dreck and end with the best so you will be left with the impression that the post was better than it was. I consider that a win-win.

So here’s the dreck.

Substack has helpfully told its writers they should remind readers that they can give paid subscriptions to Substack newsletters as Christmas gifts.

For a limited time only, they’re discounted. Exclamation mark.

Give the gift of Dan Gardner’s PastPresentFuture to loved ones. Exclamation mark.

Act now. Exclamation mark, exclamation mark, exclamation mark.

Personally, I think this is weird. (“Check your email, Sally. See anything? Yes! It’s a Substack subscription! Exciting, right? Well, better than socks? Right?”) But de gustibus non est disputandum. So if you want to do that, here are some buttons.

Sorry, Sally. I would have preferred socks, too.

But before I leave the sordid matter of money, I want to ask you a question.

Substack sets a minimum price for paid subscriptions, which the writers cannot set lower. I’m Canadian and in Canada it is, I think, CDN$7 a month. I can see why they do that. But allow me an admission against interest (as lawyers say): At $7 a month, people are paying as much or more than the cost of a subscription to a major magazine. With editors. And staff writers. And illustrators. And paper. I think highly of myself but I don’t think the newsletter I work on part-time with a team that consists of me and my dog is remotely equivalent to a major magazine.

Yet lots of you are willing to pay that much. For that, I am grateful. I expect most of you wonderful folk do so because you want to support my writing in general. Which is lovely. But for regular people, $7 a month is, over time, a lot of money to spend on a cause as exotic as keeping Dan Gardner reading and writing.

What if Substack had no minimum? What if I set a subscription price at, say, $2 a month? My guess is a lot more people would think, “sure, I’ll kick in.” Personally, I know lots of Substack writers I’d like to support but if I bought full-price subscriptions to all of them my children and my dog would starve. And I love my dog.

On the other hand, Substack has all sorts of tech weenies going over data and there’s probably much more to the problem than what I’m aware of. So I want to know your view: If kicking in a couple of bucks a month were an option, would you pay for more writers? And setting you aside, do you think others would be more inclined to kick in — so that, on balance, writers’ incomes would go up if subscription prices went down?

Next up….

Bent Flyvbjerg and I just published a new essay in Harvard Business Review. It’s about Frank Gehry, who is, of course, globally renowned as a visionary architect. But it’s not about Frank Gehry, artist. It’s about Frank Gehry, project manager.

Bent has been an admirer of Frank Gehry’s for decades, as well as a colleague, but when Bent and I first spoke about project planning and delivery, I knew only what everyone knows about Frank Gehry. And I assumed what everyone assumes: Frank Gehry does wildly innovative buildings so if you hire him you effectively give him a blank cheque, shut up, go away, and wait ages for him to eventually pull some bold new thing from his capacious imagination.

Turns out, almost all of that is false. In fact, it’s the opposite of the truth.

Gehry commonly builds the unconventional at conventional prices. He delivers on budget. He delivers on time. And far from telling the client to shut up and go away, Gehry works closely with the client the whole way along.

That would be impressive under any circumstances but when you know what the data show about project delivery (however bad you think it is, it’s much worse) what Gehry does is near-miraculous. In that HBR article we discuss how he does it.

The essay is adapted from our forthcoming book, How Big Things Get Done, set for release in early February. And available now for pre-order. (“If you’ll check your email again, Sally, you’ll see I’ve pre-ordered a book for you. It will arrive in February. Why are you crying, Sally?”)

And now, at last, I get to the non-shilling portion of the post.

If you’re a reasonably well-read person, you’ve come across the claim that most of our Christmas traditions were invented by the Victorians. There’s some truth to that. But the reality is — as usual — more complicated. Here’s an interesting essay from History Today, 2001.

…historians never seem to tire of debating the role of the Victorians in forming our modern concept of the Christmas celebration. Was it invention or re-invention? Was it an act of myth-making or simply a case of repackaging older traditions in a form that suited their modern age and appealed to the general mood?

There is ample evidence, as well as many good scholarly arguments and critical studies, to convince us that the latter is probably closer to the truth. Christmas, as we know it today, is essentially a nineteenth-century mixture of all that was best and most popular from English Christmases past, continually tempered by new sensibilities, ideas and prevailing concerns.

Chances are you have tried ChatGPT.

Chances are it left you gobsmacked, excited, and frightened, all at the same time. I’ll have more on the subject shortly, but in the meantime, I have a couple of recommendations.

I already cross-posted this interesting this list of potential historical analogies for the effects of the technology. As I noted, people tend to seize onto the first historical analogy that occurs to them, or to what they quickly judge to be the closest, and think this provides a reliable guide to how the future will unfold. That’s a serious mistake. There are always differences between any given set of circumstances of sufficient magnitude that events could be sent in quite different directions. Worse, this tendency narrows thinking. Once we have an analogy that offers the comfort of apparent foreknowledge, we stop looking for other ways the future could unfold. Tunnel vision sets in. And when we are faced with wide array of possible futures — which is always — tunnel vision can lead to a world of pain.

So how do we avoid that? I wrote about one way to use historical analogies shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. What the author above has done is different but serves the same ends. By casting about for as many analogies as possible, you quickly realize that although all the analogized events are similar in a sense, they lead to dramatically different outcomes. Conclusion? For now, the array of possible futures posed by ChatGPT and its kin is vast. That’s mind-opening, not closing. And it takes thinking and planning in quite different directions than tunnel vision would.

Also on ChatGPT, I recommend reading Ethan Mollick. He’s more enthusiastic and much less nervous than I am — not surprising given that, as a professional writer, have all my skin in this game — but his writing is provocative and interesting. To get the skeptic’s take, you must follow psychologist Gary Marcus. He’s on Twitter at @garymarcus and on Substack here. My grasp of the issues is modest — something I intend to rectify in 2023 — but Gary Marcus strikes me as the most interesting and challenging thinker doing popular writing in the field.

I loathe political activism dressed up as historical analysis. It’s not only bad history in itself, it encourages people to see history as a collection of simple morality plays. And if that is the lens through which you view history, what you will see when you look at history is far more a projection of what’s in your own mind than the reality experienced by people in the past.

That said, there’s an even worse way for the politically minded to deal with history.

All across the United States, legislators (mostly Republican) are pushing bills that effectively restrict what and how history is taught in schools and universities. These bills explicitly subordinate historical inquiry to political indoctrination. Here, the American Historical Association has a good roundup, including letters it has sent to legislators across the United States.

In Foreign Affairs, Peter Scoblic and Phil Tetlock (my co-author on Superforecasting) look at continued resistance of policymakers to quantifying probabilities — use the damned numbers, people! — and scoring predictive accuracy. When I watch sports on TV, I see lots of numbers. Batting averages. Save percentages. Every conceivable method of measuring the reality, and judging players and coaches, is applied and provided. And when I listen to analysts and even ordinary fans the level of sophistication of their use of these data is impressive. But when I watch the news, there’s none of that. It’s all vague language and hand-waving and a lack of accountability for results so complete that gasbags like Larry Kudlow never suffer in the slightest no matter how often or how badly they are wrong.

Think about that. We are, collectively, quite sophisticated in our analysis and discussion of games that don’t really matter. But when it comes to economics, business, politics, even war — the stuff of life and death — we would considerably improve discourse and decision-making if the sophistication of our analysis merely rose to the level that is routine in sports. It’s mind-boggling

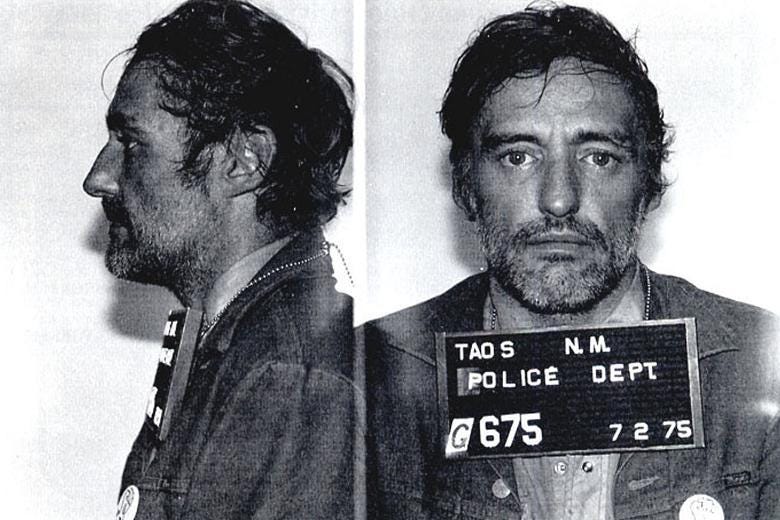

Take a look at this clip of Dennis Hopper talking with Francis Ford Coppola on the set of Apocalypse Now.

Why am I sharing this with you? Because a stoned Dennis Hopper is a hilarious Dennis Hopper. But aside from that, I love what Coppola says about Hopper learning his lines.

“If you know your lines, then you can forget ‘em,” Coppola says. “Cuz you know more or less…” and he waves his hand like a fish tail.

Coppola’s point is that the script is not something he expects actors to memorize and deliver with robotic precision. Rather, he expects them to memorize the lines in order to get a sense of where a scene needs to go and how it will get there. With that they can feel the way ahead — cue the fish-tail motion — in a more spontaneous performance that takes advantage of all the nuances and surprises the screenwriter cannot possibly foresee.

This instantly reminded me of a famous maxim which Dwight Eisenhower often repeated: “In preparing for battle, plans are useless but planning is indispensable.” On its face, it seems as paradoxical as “memorize your lines so you can forget ‘em.” But it makes perfect sense. Ike meant that nothing ever unfolds exactly as the plan anticipates. (The old military maxim is that “no plan survives contact with the enemy.”) In that sense, the plan is always wrong. And useless. But planning is indispensable because in developing the detailed plan that will surely fail, you get a far better understanding of your goal and your resources, the enemy’s goal and resources, and and what may or may not work in thwarting the enemy and achieving your goal. With that you can — cue the fish-tail motion — respond far more effectively when you are hit with inevitable surprises.

And finally, a word about Vladimir Putin.

He’s a tyrant, a war criminal, and a murderer. I hope he spends his last days in a prison cell in The Hague. Or Siberia. But in time we may realize that he may have done the world an enormous favour. To see how, cast your mind back to 1972, a time when — although people didn’t yet know it — the world was rapidly approaching the end of the long post-war boom.

Essential to that boom had been cheap energy. Coal and oil prices had long been both low and steady. And nations had responded accordingly, consuming coal and oil in ever-greater quantities while doing little to improve energy efficiency. They also became highly dependant on energy sources whose availability and abundance they took for granted. Japan, for example had revived its economy and turned that country into a leading global manufacturer almost exclusively with oil imported by ship from the Middle East.

So what would happen if those energy sources suddenly became less abundant and available? The world would be screwed. That was perfectly obvious. But few took any notice and fewer did anything about it.

Then came the 1973 OPEC oil embargo. Pundits and governments were stunned. With few exceptions, they were caught flat-footed and were suddenly forced to get through the immediate crisis and then take steps to eliminate the danger of dependency which could no longer be ignored. And they had to do that with sky-high energy prices.

The result were fundamental policy shifts that transformed energy patterns the world over, with effects felt acutely over the following two decades — and even today.

Exploration for coal, oil, and gas exploded and major new sources — the North Sea, Alaska — were developed. Synthetic programs were launched. And nuclear power was advanced in a big way. When the Fukushima disaster happened, lots of people commented on how foolish it was for Japan to have nuclear power plants near shores regularly scoured by tsunamis. But when they failed to note is that Japan had been so threatened by the oil embargo that its post-war economic miracle was widely written off with the expectation that Japan would sink back and become just another struggling poor country. Nuclear power saved Japan.

France went even bigger on nuclear power. In fact, France’s nuclear power program was the biggest decarbonization project of all time. It wasn’t built for that reason, of course. But the reduction in carbon emissions was truly massive.

Or consider Denmark, which was crippled by the embargo. It undertook fossil fuel exploration. But Denmark also has heaps of wind, so it launched efforts to develop wind-generated electricity which were initially quite minor but gradually grew — and post-2010 became the foundation of Denmark’s world-leading wind-energy industry.

So what’s this got to do with Vlad the Defenestrator?

For the last thirty years, governments have known that we have to quickly transition away from economics built on fossil fuels if we are to have any chance of avoiding catastrophic global warming. But they moved at a snail’s pace. And in many cases, they made things worse: At the same time that Germany decided to mothball its nuclear reactors because of spurious concerns for safety, it built pipelines for cheap Russian gas that deepened its dependency on fossil fuels and jeopardized European security by putting a knife at Europe’s throat and asking Vladimir Putin to hold it.

Anyone with two eyeballs could see all this. But inertia is an awesome force. It take a proportionately mighty blow to overcome it.

That blow was provided by Vladimir Putin when he invaded Ukraine.

Already it is clear that the Russian invasion shocked the world, but especially Europe, releasing a cascade of changes ranging from efforts to provide short-term relief to aggressive support for long-term, fundamental reforms. In 1973 and 1974, most of the talk was about the short-term, and it was easy to miss that the crisis had unleashed tectonic forces that would play out over decades. The same is true in 2022 and 2023. It won’t be clear for years but I think there’s a high probability — greater than seventy percent — that in future we will see this moment as a watershed when governments — especially but not only in Europe — at last got serious about long overdue changes.

And for that, Vladimir Putin will deserve considerable credit.

It wouldn’t be the first time in history that awful people inadvertently advanced human progress. Denmark’s globe-leading wind industry was kickstarted by OPEC. Scientific racism was marginalized by Adolf Hitler. The end of slavery in the United States was hastened by Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy.

That’s the thing about history. Its surprises often fall on the downside. But not always.

if I were to build something like Substack, I would provide a way to create my own magazine by paying $10/month for <N> different substack offerings, instead of paying for them individually at $4US or whatever. Because, as you say, $4US or $7CA for each individual substack adds up pretty quickly, and puts a lot of expectations on the author(s).

Absent a "build your own magazine" option for us (the customers), I would suggest you reach out to your peers and see if you can create a combined substack that does something similar to Dispatch or Bulwark, where lots of authors contribute, to spread out the burden a little

But back to your original question: yes, $2US would be a much easier decision, since it doesn't add up as quickly

I wasn't aware that Substack had a $7 CAD minimum monthly subscription cost. You are also correct that people are going to hit a max number of such subscriptions.

(You know what cost me that same amount? My subs to the NY Times, Times of London, the Globe and Mail, etc. all of which are now discounted as they don't want subscribers to leave.)

The only way around this I can see if you bundled several low output Substack writers into a single $7 subscription service, to increase the value of the subscription, and you folks split the money. (Like The Line does.)

Anyway, thanks for raising this. You should consider bundling yourself with 2 or 3 other writers with similarly high quality outputs.